Episode 2, Part 2 delivers a deep dive into the state of American and European climbing before the war, as well as the ways the rise of the Third Reich caused some of the best German and Austro-Hungarian mountaineers to emigrate, influencing climbing and skiing in America and contributing to 10th Mountain Division’s fighting skills.

The episode, which is told through the experiences of John Andrew McCown II, includes interviews with Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard; Chris Jones, the author of Climbing in North America; and Howard Koch, a veteran of the 10th who learned to climb with fellow 10th soldier David Brower before the war, and who fought alongside John McCown on Italy’s Riva Ridge during it.

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and I am so glad you’re here today, because we’re about to dive into my very favorite part of the podcast to date.

If this is the first time you’re joining us, here’s a quick recap to bring you up to speed. Ninety-Pound Rucksack is the story of the 10th Mountain Division, told in two ways. An Advisory Board of the 10th’s foremost experts helps ensure the podcast’s historical accuracy. We’re also weaving in the narrative nonfiction account of First Lieutenant John Andrew McCown II, a young man who learned to climb in the Tetons, joined the Division at its inception and rose through the ranks to become one of its greatest unsung heroes.

John’s story is part of a book I’ll release upon the conclusion of the podcast. Its factual foundation, including the recreation of events found in this episode, relies on first-person sources. Where such sources are unavailable, civilian and military histories of the unit and input from the 10th Mountain Division community are used to fill in the gaps.

In our last show, we did a deep dive into the history of skiing in America. Today, we’re going to explore the state of climbing on both sides of the Atlantic before the war, as well as how the rise of the Third Reich caused some of the best German and Austro-Hungarian mountaineers to emigrate, influencing climbing and skiing in America and contributing to 10th Mountain Division’s fighting skills. If you missed our last show, go check it out, because taken together these two episodes provide the background for the Division’s development into America’s very first unit of mountain troops.

If you haven’t already, make sure you subscribe to the show so you don’t miss an episode, and please consider becoming a Patron. Not only do patrons help to underwrite all our research for the show, they get access to our Unabridged content, which includes exclusive interviews, historical documents, supporting materials and photos that illustrate each episode. To become a patron, just go on over to christianbeckwith.com and click the Patreon button. It’s easy, and it makes it possible for us to continue this exciting and important work.

Before we begin, I want to give a quick call-out to The American Alpine Club for supporting the show.

The American Alpine Club has been supporting climbers and preserving climbing history for more than 120 years. AAC members receive rescue insurance and medical expense coverage, providing peace of mind on committing objectives. They also get copies of the AAC’s world-renowned publications, The American Alpine Journal and Accidents in North American Climbing, and can explore climbing history by diving into the AAC’s Mountaineering Library. Learn more about the Cub and benefits of membership at americanalpineclub.org, and get a taste of the best of AAC content by listening to the bi-monthly American Alpine Club podcast on Spotify, Apple podcasts, or Soundcloud.

OK, buckle up, because we’re about to rejoin John McCown and his brother Grove in the Tetons in the summer of 1939 as they embark on the first real climb of their lives.

—

John McCown could feel his brother Grove on the other end of the rope. That was the problem.

Grove was at the overhang that John had led half an hour earlier. The manila rope would go slack as he began to climb—and then it would go taut with a yank as he fell again.

John leaned back against the pull, crouching to lower his center of gravity. From his standing belay, the rope went up from his left hand, over his left shoulder, across his back, down through his right hand and over an edge at a taught, 45-degree angle toward the alpine ampitheater of Grand Teton National Park’s Dartmouth Basin, 2,000 feet below.

How sharp was the edge? How many falls could the rope take before the edge began cutting the fibers?

He had no idea. All he knew was that Grove had better get back onto the rock or he’d pull them both off the mountain.

“Behind you, on the left!” John heard their friend Ed McNeill shout to Grove. “There’s a flake for your boot!”

A moment later, the rope went slack, releasing John backward. Relief flooded through him. He began reeling in the rope in increments of inches and returned his gaze to the vista that bowled out below his stance.

It had been two weeks since the 4th of July ski race in Paintbrush Canyon, and they’d spent most of it, at Fred Brown’s suggestion, in Dartmouth Basin, a cirque so vast it was almost impossible for John to take in. Couloirs and gullies and snowfields were penciled across the landscape. To the south, a serrated series of jagged spires walled off the cirque. To the west, undulating snowslopes rolled off Table Mountain’s breadloaf-like summit thousands of feet into the basin below. A ribbon of water traced its way down the center of the basin toward Cascade Canyon, where it connected with another creek that dropped in from the opposite direction. Everything around the creeks was green: fern green, meadows of green the color of moss and clover, with forest-green pockets where stands of lodgepole pines clustered around the water.

John marveled at the lake that backed up against the basin’s jagged southern wall. It had been covered in snow and ice when they’d arrived, but with each passing day the summer sun had softened its white edges. The meltwater that now lay atop the ice was a turquoise color so shockingly out of place he kept checking to make sure it was real.

As John took in the rope, moisture peeled up off of the lake in gossamer strands that writhed and contracted and expanded in the air. Mist swirled apart and came back together until he realized with a start he was watching the formation of clouds. Or rather, he was in the clouds. He was so high up the west face of the 12,519-foot South Teton that the clouds were actually forming around him.

This was different than skiing. The landscape was the same, but even though he was higher than everything except the summits of the Middle and Grand Tetons to the north, he felt connected to it in a way he hadn’t on skis. Maybe it was the pace. The unadulterated joy of skiing lay in its speed, the way you compressed muscles and tendons into a forward lean that pushed everything aside the faster you went. The basin floor rushing up in a blur was exhilarating, but somehow, when he was skiing, John felt like he was on a slope, in a gully or couloir, zipping across a snowfield—on the land, but somehow from it. Now, as he braced his mountain boots against the ledge and expanded the broad musculature of his back in anticipation of Grove’s next fall, he felt different, as if ….

A raven burst out of the clouds and into his peripheral vision. He turned his head to watch as it rode the thermals in lilting, fluid arcs, as natural a part of the terrain as the mountains or clouds themselves.

Another raven appeared, entirely black, following similar invisible pathways. It was the first time he’d ever seen a bird from above. He couldn’t stop looking.

John had been introduced to falconry five years earlier by one of his teachers at William Penn, and his fascination had been instant and total. To a sixteen-year-old mesmerized by the possibility of a world beyond his childhood, falconry had everything: wild birds with piercing eyes and razor-sharp talons, ropes for climbing trees and descending cliffs, a strange and exotic vocabulary passed from master to apprentice in a line that stretched back for thousands of years to places like Arabia and Mongolia. The elegant beauty of a peregrine’s streamlined figure in flight, its curved, swept-back wings and mottled breast plummeting earthward at mind-boggling speeds to strike a starling out of the air stirred something primal in him. When he lowered to their cliff-side nests to take young birds before they fledged, the adults sang their shrill warnings in high-pitched screams that raked his ears, adding to a pull of danger that he found irresistable.

Cooper’s Hawks and peregrines, red-tailed hawks and kestrels, sharp-shinned hawks and broad-winged hawks and rough-legged hawks and goshawks had become his obsession. The monastic focus necessary to capture a bird, feed it, keep it free from disease and train it to hunt placed impossible demands on a schedule already stretched thin by football and lacrosse and the fraternity and the singing group and his coursework at Wharton, but it also offered an escape. As his younger brother Andrew had grown increasingly sick and his father greeted his every success with a strident insistance for even greate scholastic and social excellence, falconry had become a pressure release valve he could turn on when he otherwise wanted to scream.

He watched the second raven fly. It flew so differently than the Cooper’s hawk he’d brought from home, alternately soaring and gliding, the slow flap of its long-fingered wings making a “swish, swish” sound he could hear from his ledge.

Maybe the raven is Andrew, John thought as he watched it fly. Maybe that’s where he went after he died: he’d left his body and entered the raven’s, where the leukemia couldn’t touch him and he could move with a buoyant, soaring grace he’d never known in life, a master of the wind.

John felt a loosening in his ribs as he followed the raven’s flight. The eternal black of its long neck, its eagle-like wings and diamond tail were a vivid contrast to the mediterranean teals of the meltwater and the budding green of the alpine meadows chasing the snow higher up the mountains. As it disappeared into the water vapor of the clouds, a nameless communion opened within him, and he felt a sudden kinship with it and the landscape through which it flew. Watching the raven from so high up made him feel like he belonged here, too—an organic part of the mountain, and of all that was seen and unseen around him.

The top of Grove’s head appeared above the ledge, followed by his wire-rimmed glasses.

“That was hard!” he exclaimed, his long, rectangular face glistening with sweat. He pulled himself over the edge, panting, and scrambled past John on his hands and knees to the back of the ledge. “You went up it so fast—I thought it was going to be easy!”

“Couldn’t you stem up the outside?” John asked, laughing, as Grove swiveled to sit. “You almost pulled me off!”

“You’re taller than me,” Grove said. He was pressing his back against the rock as hard as possible, grinning an enormous, embarrassed smile. John could see the admiration in his brother’s eyes behind his glasses, and a surge of love and pride flooded over him.

“Look at the lake,” Grove said, his voice tinged with awe.

“I know,” John said. “Did you see the raven?”

–

John, Grove and their friend Ed had struck Teton gold when they’d met Fred Brown. “Things have been happening terrific fast,” Grove wrote to their parents on July 6th. “Boy, we are getting the old type connections. We can camp, fish, shoot and hike anytime… Fred is really helping us…. we have been running around terrific…. We are all fine and having a wonderful time.”

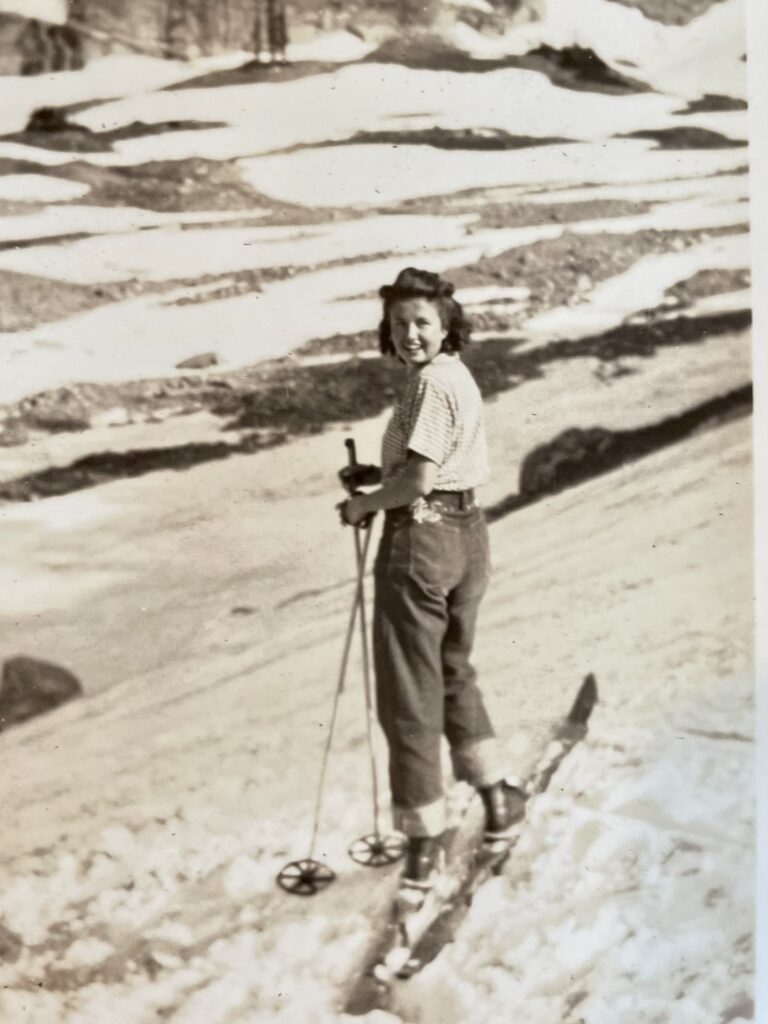

In the days following the race, Fred had taken them around the valley, introducing them to his favorite fishing holes and his friends in the local shops and a horse packer who could pack their gear the eleven miles up Cascade Canyon to Dartmouth Basin, where he’d promised them they’d find the best damn skiing in America. They’d developed budding friendships with John and Frank Craighead, identical twins whose 1937 article in National Geographic Magazine about falconry had become a sort of Bible to the McCown brothers, and the twins had taken them to eyries around Jackson’s Hole to look for prairie falcons. They’d also fallen in with a number of the people they’d met at ski race, including Chicago marathoner Joe Hawkes, a Grand Teton National Park ranger named Willis Smith, and his smart, feisty nineteen-year-old daughter, Margaret, whose budding romance with John will be included in the book (but unfortunately for you, dear listener, not in this podcast). The muse and model for Harrison Crandall, Grnd Teton National Park’s first official photographer, Margaret had climbed most of the range’s major peaks, including the Grand, by the time she was 16, and she was friends with many of the superstar mountaineers of her generation, including Paul Petzoldt and the 28-year-old American climbing sensation Bob Bates—who happened to be in the Tetons to present a movie on K2, the world’s second-highest mountain, which he and Petzoldt had attempted the year before.

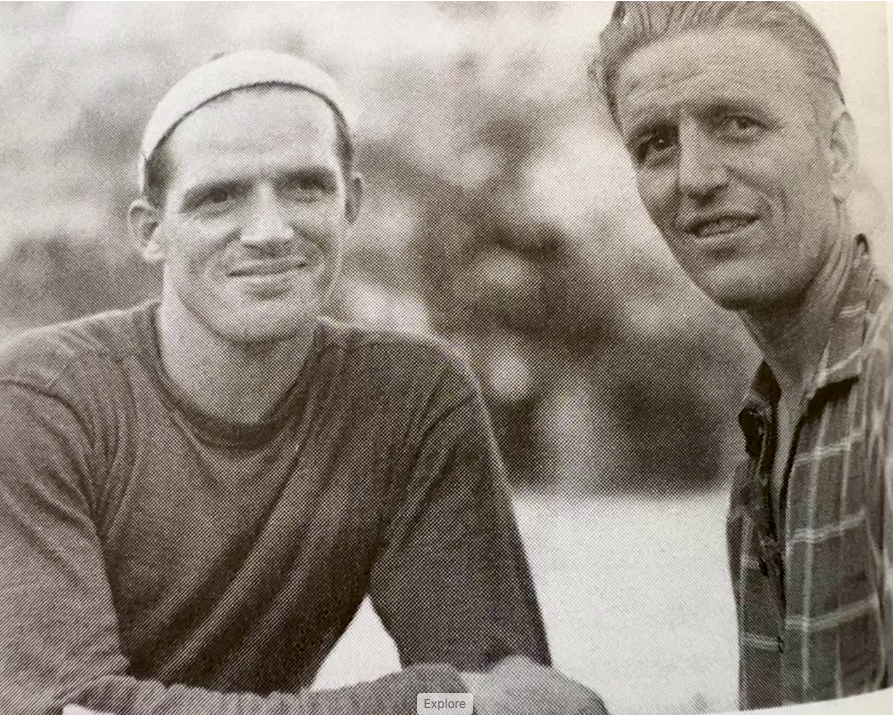

In 1939, the American mountaineering scene (if it could be called that) was miniscule. In the Tetons, the scene’s epicenter was the Jenny Lake Campground, a collection of tent sites scattered amongst the lodgepole pines along the shores of an alpine lake that sparkled with the reflections of the mountains to the west. On July 9th, John and Grove were among the audience when Bates showed his movie, and John introduced himself to Bates afterward. It must have been a funny sight: the square-jawed John, 6’2” and all muscle, leaning forward to talk to Bates, who was slight, short and a fraction of his size. But they shared a joyful enthusiasm, keen intelligence, and an alma mater in the William Penn Charter School, and they apparently hit it off, for the next year, Bates would nominate John for membership in the American Alpine Club—a proposal that would pave the way for John’s enlistment with the 10th. (Margaret and Petzoldt were nominated at the same meeting. Margaret’s nomination was approved. Petzoldt’s, as we’ll soon learn, was not.)

The next day, Bates departed for Switzerland to climb with H. Adams Carter on a trip that would, as we discussed in Episode 1, prompt the two young American Alpine Club members to begin their lobbying efforts for America’s first mountain unit.

The boys, meanwhile, embarked for Dartmouth Basin. Though the horsepacker carried most of their equipment on his mule, Ed and Grove’s rucksacks still weighed thirty-five pounds. John’s weighed sixty.

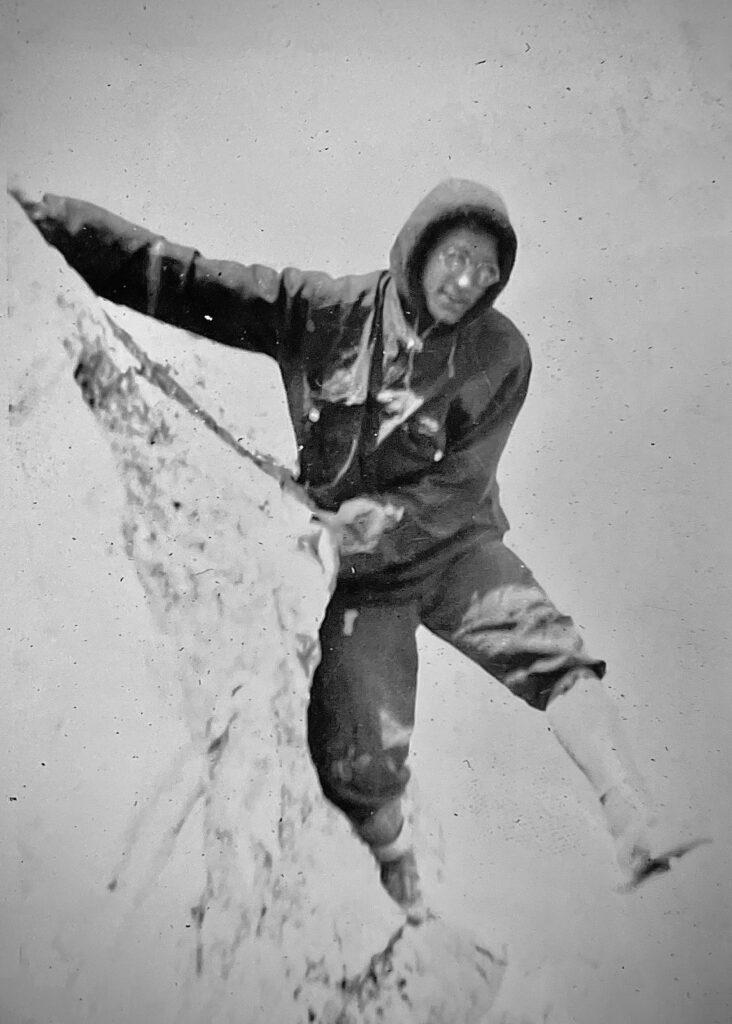

The Tetons were exponentially bigger than anything they’d ever seen Back East, and their early outings were understandably tentative. But day after day after day, calves straining, hamstrings burning, John and Grove and Ed had climbed the couloirs and gullies and snowfields of the basin in search of turns, and their trepidation had given way to a growing sense of confidence as their bodies acclimated to the altitude and they figured out how to move. They’d learned to start their days early, when the snow was still frozen, to avoid skiing the slushy deep furrows that formed under the brunt of the midday sun, and to kick the soles of their leather boots sideways to form platforms from which to take their next steps. Up up up they’d climbed, kicking into the corrugated summer snow while the sweat soaked their cotton shirts and leached from their scalps and stung their eyes and left a tang of salt on their tongues that was not at all unpleasant. As their sunburned faces and necks and arms had turned from angry red to ruddy brown, their labored breathing had developed a cadence that matched their strides. They no longer noticed the weight of the packs that had cut into their shoulders and hips so painfully the first few days. The aching soreness in their quads and hamstrings and lower backs abated. They were growing strong.

Soon enough, their oily hair no longer felt oily. The woolen socks and corduroy knickers and cotton shirts that had clung to their skin in fetid swathes now seemed almost part of it. They rose with the dawn, made their fires, ate their oatmeal, drank their coffee, shouldered their packs and set out to ski. They returned to camp hours later in a deepening light that illuminated features on the west faces of the South and Middle and Grand Tetons that had been invisible in the morning. They ate their dinners with ravenous appetites, then lingered by the fire as fatigue overcame them like a blanket and stars appeared overhead, first one by one and then in a rush of celestial pin-pricks that filled the sky. They slept. They rose. They skied, then came back to camp and did it all over again. None of them had experienced as simple or powerful an unfolding of time.

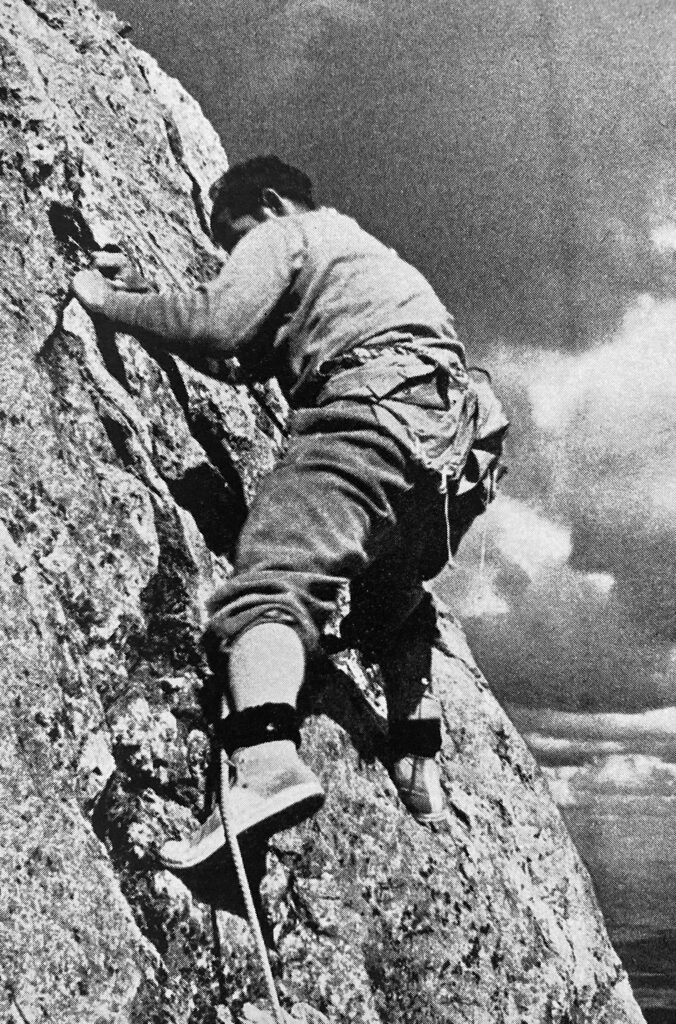

After a couple of weeks, the skiing had deteriorated past a point even the boys deemed worthwhile. The western flanks of the South Teton, which had looked impossibly steep when they’d first arrived, loomed over camp. The traveling sun had revealed new weaknesses with each passing day, and as their fitness and confidence had grown, they’d worked out a route that looked reasonable. On July 23, they left camp at 8:05 a.m. and, with John leading the way, found themselves on top by 12:30. He’d broken out the rope only once, and that was to help Grove up the overhang.

From the top, the Middle Teton beckoned to the north. Three hours later, they’d bagged the second summit of their lives. “I want to stress the fact,” John would note later about the adventure, “that none of us had climbed any real mountains before.”

By then, the skiing was officially over, and it was time to return to the valley. They scrambled up one more peak, Table Mountain, encountering 101 boy and girl scouts on top, and then, on July 30th, they packed up camp, shouldered the loads that the horse had carried on the way in, and descended to Jenny Lake. Their rucksacks were so heavy they weighed them when they got down. Grove and Ed’s weighed 100 pounds; John’s weighed 113. The locals were impressed.

The kind of fitness the boys developed in the Tetons is an organic extension of mountaineering. Venturing out for eight or ten or twelve hours at a time with packs filled with skis and ropes and axes and food and water and clothing and the heavy steel equipment necessary to climb mountains, they began to develop a combination of strength, stamina, decision-making and mental fortitude that allowed them to move efficiently and effectively over consequential terrain. It’s a unique form of fitness because it’s fueled by anticipation of the adventure ahead—and it goes deeper than any other kind of training, because it’s powered by desire. They’d begun to become mountain athletes.

They’d also begun to experience another element of mountaineering, one that’s as beautiful as it is rare. In most aspects of life, emotions and thoughts are masked by a veneer of social propriety. Nothing strips that veneer away faster than suffering. In the mountains, where cold, hunger, thirst, exhaustion, and fear are regular companions and the consequences of a mistake can be injurious or fatal, the veneer is gone, and what is left is candid and honest and raw. Relying on one another to move securely through the mountains, the boys learned to trust these more genuine versions of themselves for their collective safety and success. In climbing, this interdependence is known as the brotherhood of the rope.

I’m telling you all this for a reason. John McCown would enlist in the 10th shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. First on the flanks of Washington’s Mt. Rainier, and later on peaks up to 14,000 feet high in the Colorado Rockies, he and his fellow soldiers would master the art of suffering. They would train with packs filled with skis and ropes and axes and food and water and clothing and heavy steel equipment and sleeping bags and tents and rifles and bayonets and ammunition. In doing so, they would develop a love of mountains, and of the men who shared the experience of that love with them. As they moved over consequential terrain under adverse circumstances that stripped them of their veneers, both their fitness and their camaraderie would deepen. The typical loads in their rucksacks weighed ninety pounds.

In early 1945, John and his comrades would be inserted, completely green, into Italy’s Apennine Mountains to break the Gothic Line, a series of German-held, heavily fortified ridges and summits that had repelled Allied offensives for eight months. They would fight from the ground up, climbing toward the Germans entrenched on top with rucksacks loaded with rifles and bayonets and ammunition and grenades and provisions while the Germans rained hellfire down upon them. They would climb with stamina and fortitude and a trust in one another that had been tempered by the Colorado Rockies. They would climb while their buddies dropped beside them and hide beneath their bodies as the air thundered and crackled and whined with shrapnel all around. When the artillery paused, they would pick themselves up to continue their climb once more. They would move forward, always forward, until they broke the Gothic Line, and still they would press on, advancing against the Germans so quickly and ferociously that the US Army’s 5th Army, which had been charged with resupplying them, couldn’t catch up to provide artillery support. Their relentless attack would precipitate the German surrender of Italy, which in turn would hasten the end of the war—and when it was over they would fan back out into the mountains they’d come to love and become guides and climbing rangers, develop ski areas across the country, start the fields of backcountry survival and avalanche science and wilderness rescue, and outdoor recreation in America would roar to life.

The keys to their success were camaraderie and fitness. In 1939, during their summer in the Tetons, the boys were beginning to develop both.

“One thing is certain,” John wrote to his parents when they were back in town, “and that is that if you are in this country without a horse it is a foregone conclusion that if you are at all active you cannot help but be in wonderful physical condition. Hikes of 15 miles or so a day are thought [of] no more than walking down to the corner store in the City. At night you go to bed; when you wake up you get up; when you are hungry you eat. In other words, we did just as we pleased and by the time we got through skiing, about the last of July, we were in pretty fine [shape] and ready for the mountains.”

—-

After a few more days with Fred and his family, the boys shifted their base of operations to the Jenny Lake campground, where they soon started meeting the rest of the climbers who were passing through the range that summer. There weren’t many.

As you’ll remember from our last episode, American skiers before the war numbered somewhere between one and three million. Climbing did not enjoy a similar level of popularity.

There were five epicenters of American climbing at the time of the boys’ visit: the east coast, Colorado, the Tetons, California, and the Pacific Northwest. Apart from the Tetons, they all had organizations dedicated to the mountains.

The east coast was represented by two main organizations: the Boston-based Appalachian Mountain Club and the New York-based American Alpine Club. The AMC, which, as we discussed last time, was also pivotal to the development of alpine skiing in America, had 4,670 members in 1939. The American Alpine Club, which was modeled on the invitation-only Alpine Club of Britain, had fewer than 300 members.

The Colorado Mountain Club had been established in 1912. In 1939, it had 550 members. On the west coast, the country’s second-oldest mountain club, the California-based Sierra Club, had 3,794 members as of December 1941. Oregon’s Mazamas boasted 690 members in 1939. The same year, the Seattle-based Mountaineers had 600 regular and 103 junior members, plus 31 spouses.

Add all these numbers up and you find that some 10,677 people were members of the country’s leading mountaineering organizations. Factor in the membership of university groups like the Dartmouth and Harvard and Yale mountaineering clubs and that of a number of smaller organizations scattered around the country and the number rises to around 12,000. By comparison, the German and Austrian Alpine Club—Deutscher Alpenverein, or DAV for short—had around 200,000 members before the war.

The art of hiking, scrambling and climbing is broken down into a classification system that runs from Class 1 to Class 5. Class 1 is hands-in-pockets walking. Class 2 is straight-forward hiking, with one’s hands used from time to time for balance. Class 3 is scrambling, often with hands out to prevent a fall that could result in injury. Class 4 is a mix of scrambling and climbing. It often includes exposure, where a fall could be fatal and a beginner might want a rope. Class 5 is technical climbing; routes are typically broken down into pitches, where a pitch is the length of a rope, and belaying and points of protection are used to safeguard climbers from the consequences of a fall. Climbs tend to get harder as they get steeper, and the Yosemite Decimal System assigns an additional number to fifth-class climbs to further delineate the difficulty; by the time one is on 5.8, for example, most of one’s weight is usually on one’s fingers and toes. Starting at 5.10, a letter system that runs from a to d provides even greater granularity. A 5.10a is easy 5.10. A 5.10d is hard 5.10. At the time of this writing, the hardest climb in the world is 5.15d—very small holds on completely overhanging terrain.

How many of America’s 12,000 card-carrying members of its various mountain organizations were technical climbers in 1939? After a lot of deliberation and research and talking to other climbing historians, my best estimate is that there were fewer than 500.

Many if not most of these climbers lived in the East, which enjoyed proximity to Europe and thus served as the landing spot for the new techniques and equipment that the well-to-do climbers like H. Adams Carter and Bob Bates brought home with them from their holidays in the Alps. A smaller but increasingly influential number, as we’ll soon learn, were Sierra Club climbers from southern California and the Bay Area. All these climbers would come to play significant roles in the development of the 10th.

Geographically isolated, and absent an urban population center, the Tetons didn’t have a mountaineering club. Still, the range had emerged, by the time the McCowns arrived, as the heart of American mountaineering, a destination where climbers could test themselves on peaks that were at once formidable and accessible. “With each season the Teton Range of Wyoming becomes more firmly established as a climbing center,” Grand Teton National Park’s first climbing ranger, Fritiof Fryxell, noted in the 1935 American Alpine Journal, aka the AAJ. In 1933, 73 ascents had been recorded in the Cathedral Group, the knotted clutch of peaks that comprise the heart of the range. In 1934, that number increased to 103. The summer of the boys’ visit, 163 ascents were made of the various summits. And while the majority of the climbing was focused on the Grand, all the major peaks in the range got their share of attention.

It wasn’t just the number of climbs and climbers that was increasing; the caliber of the climbing was going up as well. “When the history of mountaineering in the Rocky Mountains of the United States comes to be written,” intoned one of the preeminent climbers of the 1920s, Albert Ellingwood, in the 1930 AAJ, “a new chapter will begin about the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century. At that time few, if any, peaks of major importance remained unclimbed. The more energetic climbers therefore turned their attention to ascents which were attractive because of their technical interest rather than because of altitude.”

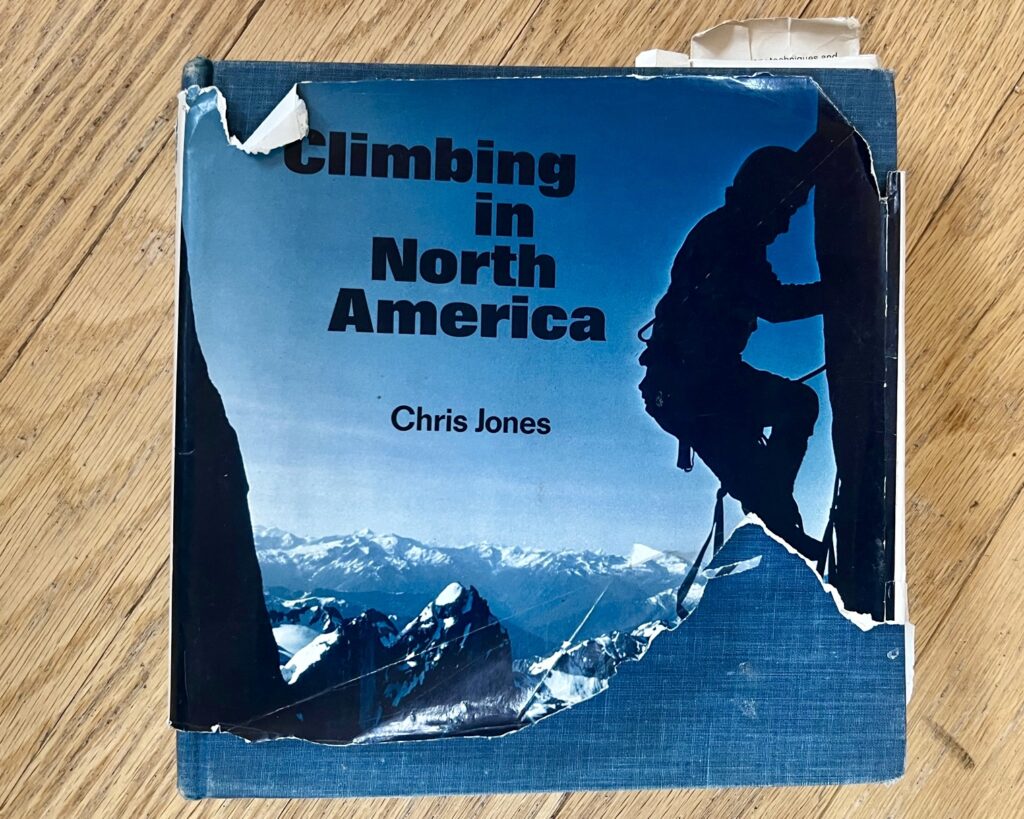

Chris Jones, a British expat who cut his teeth on hard new routes in Britain and the Alps, was lured to America in 1967 by the explosive possibility of Yosemite’s big walls. He proceeded to establish some of the hardest alpine and rock routes on the continent, and in 1968, along with a ragtag group that included Yvon Chouinard and Doug Thompkins, made the third ascent of Patagonia’s Fitz Roy, one of the world’s great mountains, as part of a five-month-long, van-living, break-surfing, mountain-skiing California-to-Argentina road trip that launched the outdoor recreation lifestyle as we know it today.

In 1975, Chris wrote the country’s first climbing history, a seminal volume called Climbing in North America that quickly became required reading for anyone who fancied themselves a climber. In it, he detailed American mountaineering’s evolution from the quixotic pursuits of a few eccentric individuals in the 19th century to the scientists and surveyors of the mid to late 1800s who climbed mountains as part of government-backed exploratory expeditions to the fame-seekers and ancestors of modern mountaineers who knocked off the big ones: Mount St. Elias, Denali, the iconic peaks of the Canadian Rockies, and mountains like the Grand Teton.

As with skiing, climbing in North America had European roots. Those who had the means traveled to Europe, climbed with guides and brought their lessons home, where they applied them to objectives in places like Alaska and the Yukon and the Canadian Rockies that shared the glacierated architecture of the Alpine peaks on which they’d learned to climb. Unlike skiing, however, where Americans were achieving levels of proficiency that were at least within shouting range of European standards by the time of the war, American climbing, with few exceptions, remained wildly behind the curve.

To get a better sense of why that was, I decided to give Chris a call.

[Chris Jones Interview]

CJ: I’m Chris Jones, ancient writer of history of American climbing. I was very privileged during the research on my book to meet so many of the instigators of technical climbing in North America.

I asked Chris to help us understand some of the factors that contributed to the advanced state of European climbing before the war.

CJ: The European Alps were basically inhabited. The valleys had been used as pastures for thousands of years. There were villages, there were towns, there were railroad systems, there were public transport and primitive roads, and so they were very accessible. Someone from the city, you know, Munich or Hamburg, what have you, it would be reasonable for them to go and spend a weekend in some of the nearer alpine bases. Whereas, you know, some of our cities were really—you couldn’t really reach the mountains terribly well with the state of transportation. We had the North Cascades in North America or the Canadian Rockies, but there weren’t people living up in the valleys. You know, they were sort of untraveled areas, and so if you wanted to get around in the Canadian Rockies, you had to, in the early days, take a pack, train and thwack your way through the brush.

By the time the Grand Teton was first climbed in 1898, mountaineering in the European Alps had already entered its golden age. Edward Whymper and his team of British climbers, led by their Swiss guides, had climbed the “impossible” Matterhorn in 1865; the majority of the remaining major Alpine peaks had received their first ascents by 1880.

CJ: I think you have to appreciate the fact that American technical climbing didn’t really get going until, let’s say the mid twenties, whereas high standard climbs have been done in the Alps for a tremendously long time. I think it was in something like 1900 that Tito Piaz soloed a seven-pitch route in the Dolomites on Punta Emma. I mean, a very, very steep climb, solo, seven pitches—at that time in America there was, well, there was just nothing going on, you might say. And so Europeans had this tremendous start—again, with the mountains being so accessible, lots of climbers in them. Climbing was sort of a recognized activity in the Alps and the Alpine countries.

As Jones writes in his book, “The advance of mountaineering in North America required a class of men with the leisure and the desire to indulge in an adventurous pastime. Throughout the early years of climbing in North America, the majority of the accomplished climbers came from the east. The East first witnessed industrialization, the growth of large cities, and the rise of a well-educated professional class. These people had the time and money to travel and to indulge in leisure pursuits.”

CJ: We’ll have to recall that those who are climbing, for the most part in the pre-war era, the time of the Depression at least, were fairly well to do. They came from professional backgrounds, they taught at universities, or they were bankers or lawyers, or they owned businesses. It was often easier in the 1920s and earlier for someone on the east coast to get a good season of climbing by going to the Alps. They’d have to sit in a boat for a time. But once they were there, the access to the mountains was quick and there were guides—versus going to, let’s say Mount Rainier area or Canadian Rockies, where the long tedious journey by train and then access to the mountains was much more difficult. So really in terms of bang for the buck, they were probably better off going to Europe, and that’s why many of them in fact did.

Much like skiing in the 1920s, the socioeconomics of climbing skewed heavily toward the rich.

CJ: The social dynamics in North America were still very much like they were in Great Britain at that time. It was sort of an occupation for the more leisured classes. That was to change, of course, in Britain and perhaps more quickly in the Alps where local guys, God knows what their trade was, they were up in the mountains, they were doing the climbs, you know, they didn’t need to belong to any fancy clubs or anything. One can perhaps say that’s part of the reason why the DAV (German Alpine Club) had some 200,000 members or what it might have been because, you know, it was open to everybody, whereas let’s say the American Alpine Club, you had to be proposed then seconded and then you had to climb all these kind of peaks. But the proposing and seconding was a sort of a veiled way of keeping out socially undesirable people. How the British and at that time, the American, Alpine Clubs, were exclusive and so the numbers were almost deliberately kept low, which of course, cascading effects: none of the hot new climbers could get in blah, blah, blah.

In America in the late 1930s, there was perhaps no climber as accomplished as Paul Petzoldt. As we mentioned earlier in the episode, Petzoldt had been nominated for membership in the AAC by Bob Bates, at the same meeting that John McCown and Margaret Smith—two strong but young climbers with less than a decade of experience between them—were approved for membership. Petzoldt’s nomination was seconded by Bill House, another of the country’s leading alpinists, and one who would go on to play a vital role in the 10th.

The meeting was held at the Club’s headquarters at 140 East 46th Street, New York City, on Saturday, November 30, 1940. According to the meeting’s minutes,

“There was a ten-minute discussion about Petzoldt, about whom there were considerable differences of opinion. Houston and Bates expressed strong opinions in his favor, as did House by a letter. All agreed that Petzoldt is a first-class climber and companion on the mountain. Less favorable aspects seem to be his relations with other people outside of climbing, and a feeling by some that his alleged truculence and differences with people might get him into situations, as a well known climber, which if he were a member might cause embarrassment to the Club. Washburn brought up the question of his full time professionalism….”

Petzoldt’s nomination was tabled.

There is one north face in American alpinism, and it is the north face of the Grand Teton. Bookended on the east and west by ridges that strain to contain it, the face rises three thousand feet from the Teton Glacier like the flat side of an ethereal spear. It is dark, cold and foreboding, and its shadowed rock is laced in latticeworks of snow and ice.

There are numerous north faces in European alpinism. One of the most famous is the 6,000-foot north face of the Eiger, which soars up from the bucolic Swiss countryside like a malignant shadow. Its mottled limestone is grouted by ice, and when the ice melts it unleashes a barrage of rockfall that strafes the walls and everything in its path. The mountain seems almost to crouch forward with its massive eastern and western flanks to enfold the face like the wings of a phantasmic raptor.

What these two great walls share is a magnetism that is at once romantic, alluring and repellant. In the mid-1930s, they represented the outer limits of conceivability for the leading Alpinists of the day. Only the very best dared imagine climbing either one of them.

Who made the first ascent of the Grand’s north face? Paul Petzoldt, in 1936, with his brother Curly and Jack Durrance, one of the hot new climbers of the day (and one who, not coincidentally, had learned to climb in Munich). When Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vörg, Heinrich Harrer and Fritz Kasparek made the first ascent of the north face of the Eiger in 1938, it was already known as the Mordwand, or death wall, for all the top-notch alpinists who had died trying to climb it. The north face of the Grand is a phenomenal route, enormous, objectively hazardous and psychologically intimidating, but the Eiger’s north face is an order of magnitude harder. It also helps underscore some of the fundamental differences between European and North American climbing.

CJ: Let’s take the Eiger for example. There’s a little village down below, Grindelwald, and you can sit in the Kleine Scheidegg hotel and look through a telescope at the north face. So there was actually a funicular railroad going up inside the mountain and there was a station at the top. In other words, it was immediate and there it was. And so they were able to up their standards quite quickly. Now, in the Tetons, the first decent climbs weren’t until the early 1920s, and so they had a lot of catching up to do. There were very, very many more climbers in the Alps, highly skilled climbers, by the way, then there were in the Tetons. And so to even expect there’s an equivalence between the north face of the Grand Teton and the Eiger, it would be naive in the extreme. I’m hard pressed to tell you by the way, when it was, it was the climb in North America equivalent to the Eiger but it certainly wasn’t till way after the second World War—way after.

It’s difficult to overstate the gap that existed between North American and European climbers in the early part of the 20th Century.

CJ: In terms of knowledge of using the rope and gear, the Europeans were ahead.

Before visiting Eastern climbers Ken Henderson and Robert Underhill arrived in 1929 with their Alpine equipment and know-how, nobody in the Tetons had ever rappeled; they’d simply ascended a mountain like the Grand, and then climbed back down. At that point, the basic body rappel had been in widespread use in the Alps for more than fifty years. Glenn Exum made his famous solo of the Exum Ridge, a 1,500-foot Class 5 climb rated 5.5 on the Yosemite Decimal System, in 1931, wearing football cleats he’d borrowed from Paul Petzoldt that were two and a half sizes too big. Though his footwear was likely more appropriate, Italian climber Tito Piaz had been soloing longer, harder routes in the Dolomites since 1900. Speaking of solos, Austrian Paul Preuss soloed the first ascent of the 900-foot East Face of Campanile Basso at 5.7 on friable rock with a heavy pack in 1911, then descended by down-soloing an equally-difficult route. The list goes on and on, with and without ropes: Benedikt Venetz led the crux of Chamonix’s 10-pitch Aiguille Grepon at 5.6 wearing tricouni-nailed boots in 1881. In 1899, Otto Ampferer and Karl Berger made the first ascent of a 21-pitch 5.5 on Campanile Basso in the Dolomites; by 1934 the route had received 619 ascents. In 1901, Beatrice Tomasson and her two guides, Bettega and Zagonel, opened the era of big-wall climbing when they made the first ascent of a 21-pitch route on the 2,500-foot south face of Marmolada at 5.5 using only four piton rings for anchors. No comparable climb would be made in the US until long after the second world war.

All the revolutionary climbing techniques—the rappels and tension traverses, the direct-aid climbing that relied on gear for advancement rather than fingers and toes, the concepts of belays and solid belay anchors and hanging bivouacs, the cutting of steps and frontpointing necessary to climb snow and ice routes—had been developed in Europe. The ropes and pitons and carabiners and ice axes and crampons that accompanied the world’s best climbers on the world’s hardest climbs had been developed in Europe, too, as early as the beginning of the century.

European climbers could buy state of the art clothing and equipment directly from climbing shops in places like Chamonix, Munich and Vienna as early as 1906. Until 1935, when Lloyd and Mary Anderson from Seattle started selling imported gear at discounted rates in a business endeavor that would come to be known as REI, American climbers had two choices: order their gear from Europe or make their own. German and Austrian and French and Italian climbers learned the cutting-edge techniques from handbooks that reflected generations of mountain knowledge. Apart from a handful of articles in publications such as the AMC’s Appalachia, the American Alpine Journal and the Sierra Club Bulletin, Americans didn’t. By the time of the McCown’s Teton visit, Europeans had developed a sophistication and technical mastery of the pursuit that allowed them to open routes Americans simply couldn’t conceive of climbing.

This is not to say that every aspect of American climbing lagged behind that of the Europeans.

Carter and Bates were among the well-to-do Easterners who applied what they’d learned in the Alps to objectives in Alaska and the Yukon that were exponentially wilder and more remote than anything on the European continent, and then parlayed those experiences to expeditions to the Greater Ranges, as the high mountains of Asia are known, in ways that rivaled or exceeded the best European efforts of the day. The 1932 first ascent of China’s 24,790-foot Minya Konka, made by a small American team that included Carter and Bates’ Harvard Mountaineering Club companion Terry Moore; the 1936 first ascent of India’s 25,643-foot Nanda Devi, an expedition Carter helped put together in his Harvard dorm room; and the 1938 K2 expedition, on which Petzoldt achieved the highest point yet climbed by man, were a direct function of the experiences the Americans had had on their home turf. Europeans, accustomed to a more civilized type of Alpinism that permitted an audacious ascent followed by a pipe, a proper glass of brandy and an assemblage of enraptured onlookers as they retraced their itineraries with their walking sticks from the decks of adjacent hotels, had no comparable terrain on which to train. And, once war broke out, the Americans’ adventures in the Far North would be put to good use when Bates and company organized expeditions to Alaska and the Yukon to test equipment for the 10th.

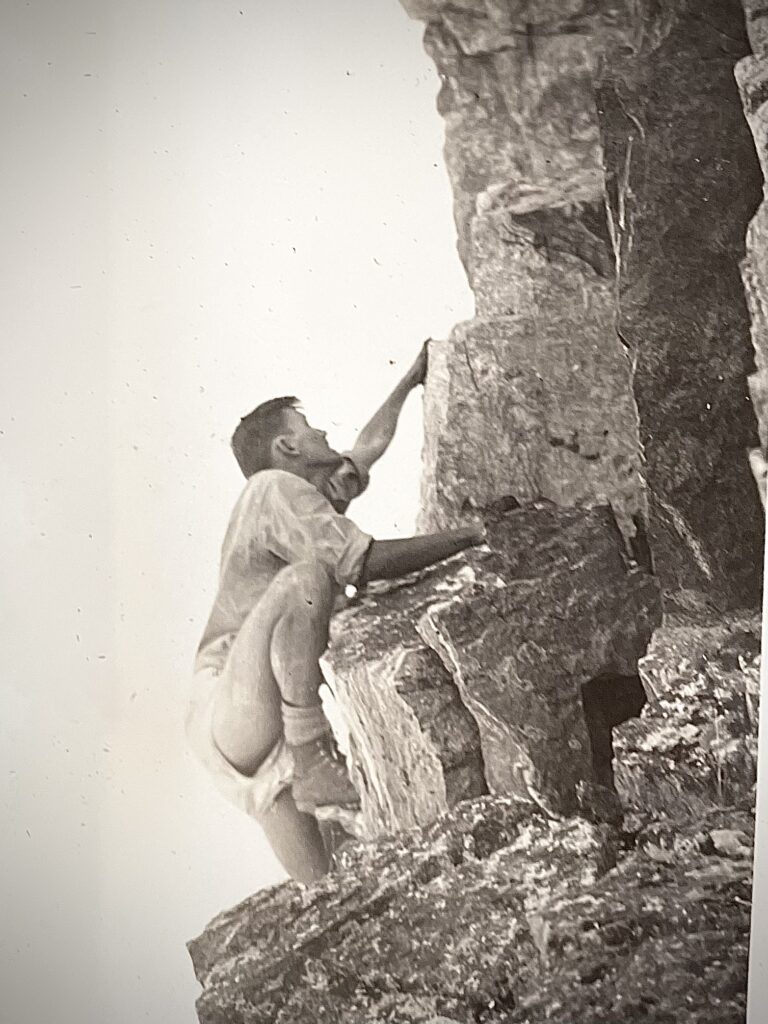

Californians were making advances of their own. In the early to mid 1930s, a small group of Sierra Club climbers that included Bestor Robinson, Glen Dawson, Dick Leonard, Raffi Bedayn, Jules Eichorn and David Brower began to emerge as the progenitors of a distinctly American school of climbing.

CJ: The Sierra Club pretty soon surpassed the Europeans knowledge of belaying. I remember climbing in the Alps, and the crags in Europe in the 1970s and seeing what the French considered a belay, for example. It was just standing there with a rope hitched through a piton, and the Sierra Club had gone way beyond that. In the 1930s, they actually studied how to belay.

With little information at their disposal, they experimented with the physical limitations of ropes, belaying, and pitoncraft, skills they then applied to the outrageous granite walls of Yosemite Valley and on objectives like Shiprock, a formidable volcanic plug in the American desert.

CJ: The very first climb that they really focused on in Yosemite was the Higher Cathedral Spire. At that time, the blank faces looked completely impenetrable, but they did think that they could climb the various rock outcroppings in the forms of spires and pinnacles around the valley. And they focused on the Higher Cathedral Spire, which is quite an intimidating objective actually. And so basically that’s where they learned. They went up the first time and they took, you know, nails from a hardware store to bang in the rock and everything. And it didn’t get very far, but learned on the job training there. The next time they went back, as I recall, they’d written off to Sporthaus Schuster for some pitons and farabiners, but they also learned studying various instruction manuals that they obtained from Europe.

These experiences, too, would have direct repercussions for the 10th, when those same Sierra Club climbers applied their knowledge and ingenuity to the development of techniques, clothing and gear for the troops to use.

Perhaps none of the Sierra Club climbers were as important to the 10th as David Brower. Born in 1912, he was six-foot-two and a lean 170 pounds with big shoulders, dark brown hair, blue-gray eyes, terrible teeth and an innate optimism that drew its energy from those around him. Brower was a gee-wiz guy, extraordinarily smart, easily thrilled and fascinated by the natural world and the way it worked. During the war he would not only serve as a mountaineering instructor for the Division; he would help develop its gear and clothing and edit a manual of ski mountaineering that in turn would inform the War Department’s training manual for the mountain troops.

So when I discovered that there was a veteran of the 10th who learned to climb with Brower, I jumped at the chance to talk to him. His name is Howard Koch.

[Howard Koch Interview}

HK: I was born in Oakland January 19th, 1925. Well, David Brower was with the Sierra Club and David taught me how to climb. We had some good guys in the Sierra Club; there were good climbers like Raffi Bedayn and Dave Brower and Dick Leonard. They knew a lot more than I did about climbing.

CB: And so what were you climbing with? I’m so curious. Did you have kletterschuhes or tricouni-nailed boots?

HK: I started with Keds, yeah, that was good enough for the rock that I was climbing on and yeah, I never had kletterschuhes.

CB: And what was your first experience? Do you remember the first time you went climbing?

HK: Oh yeah, I’ll tell you that we were climbing up on maybe it was Craigmont when we started there, that’s where we, like on the weekends we could go for like a Saturday or a Sunday, you could go up on the rocks and climb. And Dave Brower was one of our instructors and there were a lot of people that could show you how to tie the knots and stuff like that.

CB: Were you typing directly into the rope?

HK: The bowline on a bight.

CB: Mm-hmm. Well, I mean I haven’t actually used that. I used harnesses, but I know that when you were climbing, harnesses didn’t exist.

HK: We didn’t have harnesses.

CB: So what techniques were you learning when you were a teenager? You were 16 or 17?

HK: Probably 16.

CB: And what did you, what were those lessons like? What did you first learn from David?

HK: First we learned to tie into the rope. We also know that we could use 120 foot rope. We had at that time sisal ropes and would tie into the rope and usually one of the better climbers led. And then the other two guys, the middle guy and the guy in the end each one had to know how to climb and also belay. We learned how to belay and we learned to rappel and then they showed us how to use hand holds and different things to get up the mountain.

CB: And were you using pitons and hammers?

HK: Pitons and hammers and learning how to use them and learning how the pitons go in the rocks and the right way. And sometimes when we drove it, the piton didn’t stay.

CB: Where were you buying your equipment? I know it was difficult to find back then.

HK: There were a couple places around the Bay Area that would sell you sisal rope and things like that and pitons and I guess they got somebody to make pitons for ’em. And we had carabiners.

CB: Maybe from Germany.

HK: From Germany, probably a lot of people came from Germany and Austria, you know, they had immigrated from Europe because of Hitler. You know, they didn’t, some of those Austrians in the Germans didn’t wanna be in Hitler’s army, so they somehow got out of there and got to the United States. Then we were fortunate to have near Oakland the Sierra Nevada Mountains. And of course Yosemite Valley had some wonderful climbs and I made some climbs in Yosemite Valley with some guys that knew a little bit more about it than I did. Cathedral Spire.

CB: Oh wow. Did you really?

HK: Yeah, one of my climbs was Cathedral Spire. That was like, what’s it called? A class six, I think.

CB: Was that before or after the war?

HK: Before the war, yeah.

CB: Wow, Howard. Okay. You were getting after it. That was one of the more innovative climbs in America at the time.

HK: Oh yeah, and I climbed Washington Column.

CB: wow.

HK: I had a first ascent in one little place in Sequoia National Park. So I have a first ascent there.

Howard Koch, ladies and gentlemen! Not only was he climbing before the war–he was throwing down, in one of the few places in the country that were giving the Euros a run for their money.

Howard was part of a trend, if that’s the right term for a pursuit with a handful of participants.

As one of the preeminent climbers of the 1920s, Albert Ellingwood, intoned in the 1930 AAJ, “When the history of mountaineering in the Rocky Mountains of the United States comes to be written, a new chapter will begin about the end of the first quarter of the twentieth century. At that time few, if any, peaks of major importance remained unclimbed. The more energetic climbers therefore turned their attention to ascents which were attractive because of their technical interest rather than because of altitude.”

When Ellingwood, a Colorado College professor who had lived in England as a Rhoades Scholar, returned home, he applied the technical skills he had learned from the Brit to groundbreaking routes in Colorado’s San Juan mountains that stood as the most technically advanced climbs the country had ever seen. In 1923, he traveled to the Tetons, and over the course of three days made the third overall ascent of the Grand and the first ascents of the Middle and the South Tetons, ushering in both an energetic approach to mountaineering and the first modern applications of ropework in the range.

Paul Petzoldt had been pushing the boundaries of American climbing in the Tetons since the 1920s, making up for a lack of knowledge with sheer strength and inimitable will. In 1936, he brought a young man named Jack Durrance to the range to work for him as a guide. Durrance, who’d learned his skills on the crags and in the mountains around Munich, was part of a new school of technical climbing that embraced a liberal use of pitons to safeguard powerful, dynamic movements key to the routes of the future. When he hit the Tetons, he went off, establishing routes beyond the capacities of even a phenomenal pioneer like Petzoldt to envision. Whether that was why Petzoldt declined to pay him is unknown, but Durrance ushered in groundbreaking routes such as a direct start to the Exum Ridge and the first ascent of the Grand’s distant west face that stood among the hardest climbs ever achieved on American soil.

These were incredibly significant developments for American climbing, and they weren’t alone. As important as they were, though, they still lagged decades behind those of their Continental counterparts.

——

There was another factor at play in American climbing before the war as well.

When the McCowns set up their tent in the Jenny Lake Campground, they were surprised to find themselves in the middle of a cosmopolitan neighborhood. In addition to climbers from the Dartmouth Outing Club and the Harvard Mountaineering Club and the Seattle Mountaineers were climbers from Missouri and Iowa and New Jersey. There were also foreigners who, lured by the Grand’s growing reputation as America’s Matterhorn, had traveled from Spain, Switzerland and New Zealand to climb it. “That each year an increasingly large number of foreign climbers visit the Tetons may be taken to indicate a growing interest in this range abroad,” Park Ranger Fritiof Fryxell had observed in his 1933 mountaineering notes. “The past season there were climbers in the park who registered from Bulgaria, Austria, Germany, England, Scotland, Tasmania, and Australia.”

German and Austro-Hungarian emigres with Alpine backgrounds were particularly well-represented in the campground. On August 3, the day, as you’ll remember from our last episode, that John would find himself on the Grand’s Exum Ridge, Norman Dyhrenfurth, the German son of Himalayan explorers Gunter Oskar and Hettie Dyhrenfurth, was having an adventure of his own on the mountain’s east ridge. Also present in the range were sixteen-year-old Friedrich Wolfgang Beckey (“Fred” for short) and his thirteen-year-old brother Helmut (or “Helmy”), who, between July 15 and July 20, climbed the Middle Teton, Nez Perce, the Grand, Teewinot and the South Teton, in that order. Fritz Wiessner, a free-climbing prodigy who had established climbs up to hard 5.10 in the Saxony and Dolomite regions before emigrating to the US in 1929, had visited the range in 1936, making an ascent of the Grand’s north ridge, one of the hardest routes in the country, during his visit.

These climbers had something in common.

Their immigration to the United States had been catalyzed by the socioeconomic polarization that engulfed Germany following World War I. Dyhrenfurth’s parents had been awarded a gold medal for alpinism at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, but his mother was half-Jewish. The Beckeys’ parents—Klaus Beckey, a surgeon, and Marta Maria Beckey, an opera singer—had fled their home in Düsseldorf to escape economic hardship.

Brothers Joe and Paul Stettner, after whom the Grand Teton’s Stettner Route is (mistakenly) named, offer a snapshot of the dynamics at play in Germany before the war, as well as how they affected American climbing. Born five years apart in the Bavarian city of Munich, the pair emigrated from the mid-1920s during the ascendency of Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. On May 2, 1919, their father, Joseph Sr., a left-leaning union leader and activist, had been killed while intervening on behalf of a one-legged World War I veteran who was being harassed at a roadblock by members of the right-wing Free Corps, which had just taken over the city. When Joseph Sr. reprimanded the hooligans, a fight ensued. One of the young men shot him in the kidney. He died shortly thereafter, bleeding out—but not before stabbing the thug in the chest with his knife.

Their father’s death marked Joe and Paul as “sons of a revolutionary.” Fearing a similar end for her children, their mother arranged for Paul, then 18, to immigrate to Sweden in 1924. The next year, she sent Joe, 24, to Chicago, where her sister already lived. Joe’s loneliness without his brother, which was exacerbated by his lack of English, ended in 1926 when Paul joined him in the Windy City and their contributions to American climbing began.

The brothers are best known for their 1927 first ascent of Stettner’s Ledges, a six-pitch 5.8 on the east face of Colorado’s 14,259-foot Longs Peak that they’d climbed with 120 feet of borrowed half-inch sisal rope. The route was one of the country’s most technically advanced alpine rock climbs of the day; nineteen years would pass before it was repeated. By the time they visited the Tetons in 1936, they’d already established a flurry of follow-ups in the Colorado Rockies, including an eleven-pitch 5.7 on the north face of Lone Eagle Peak and “Joe’s Solo,” an 800-foot 5.6 on the east face of Longs that was so bold that historians doubted its authenticity. Joe onsighted it, alone, in the aftermath of a divorce.

What these routes fail to illuminate is the training and preparation that preceded them, and that emigres like the Stettner brothers brought to bear on their American climbs.

By the time their father was killed, Joe was 18, and Paul was 13. The pair had already begun escaping the chaos of a post-war Germany with increasingly ambitious trips executed on microscopic budgets to the rugged upthrusts of glaciated limestone north of Munich that had served as the proving grounds for generations of alpinists before them. They’d grown up in a climbing culture. Though they were inexperienced, they were methodical, studying the climbs and techniques of the alpine legends of the day, and setting itineraries for themselves that those alpinists had used to become Europe’s best climbers. Before trips, they would go to the Alpine museum in Munich to study relief maps of their objectives. They practiced climbing on the rock walls of Munich’s klettergartens. They hiked for days, borrowed ropes, slept in their raincoats and climbed routes that, by dint of the fact that they didn’t kill them, made them stronger. Perhaps most important, they climbed with the audacity of youth. “We stuck our necks out a lot, but we got away with it,” Joe told Jack Gorby, who documented the brothers’ lives in his biography, The Stettner Way.

Back in Munich, though, their climbs didn’t matter. As we mentioned in Episode 1, The Treaty of Versailles, which was drawn up at the end of World War I by the victors, had imposed penalties on Germany that simultaneously demoralized the nation and plunged it into economic disaster. By November 1923, as William Shirer noted in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, “it took four billion marks to buy a dollar… . German currency had become … worthless. Purchasing power … was reduced to zero. The life savings of the middle and working classes were wiped out. But something even more important was destroyed: the faith of the people in the economic practices of such a society.” National despair paved the way for the rise of right-wing ultra nationalists—and as political power passed to the right, even climbing was affected.

The Stettner brothers had joined the German Alpine Club in 1922, mainly to secure access to its mountain huts. But the DAV, like almost every other strata of society, was soon infiltrated by the Nazis. “I was constantly afraid of being arrested because I was the son of a revolutionary,” Joe told Gorby. “It was a problem for all of us.”

The Nazi infiltration was intentional: it had been engineered by Hitler as part of his plan to occupy every strata of society. But there were other factors at play as well. The Treaty of Versaille had limited Germany’s standing army to 100,000 men. To get around the constraint, Hitler used the DAV to train alpinists who would later become German mountain troops. Any resistance to Hitler’s right-wing anti-semitism had already been purged from the Club. The DAV had begun to exclude non-Christian members as early as 1899, and it banned Jews, who made up a third of the membership, in 1918. By the late 1920s, Jews were also prohibited from using the Club’s mountain huts.

Immigration to America allowed the Stettners to escape Hitler’s reach and start over. Their father had secured apprenticeships for them as children, Joe as a coppersmith and Paul as a photoengraver, and in Chicago they secured jobs accordingly as they began the uniquely American process of assimilation. They worked their asses off, bought two Indian motorcycles for $400 each, ordered pitons from Germany, joined a German-American hiking and social club, and began exploring the crags of Wisconsin’s Devils Lake on the weekends. They got two weeks off a year, and they used them in September because that’s when they used to climb in the Alps, riding on their Indians across the dirt roads of America to its highest mountains.

As with some of their fellow emigres, the Stettner brothers brought superior equipment and the knowledge of how to use it to America. The result helped catalyze a rise in standards in their adopted country—and, as the dark shadow of war began to stretch across the Atlantic, Europe’s loss would become America’s gain.

Prevented by his citizenship status to enlist with the US Army, Fritz Wiessner would serve as a technical advisor to the 10th instead. Fred Beckey would join the 10th at Camp Hale. Joe Stettner, who was too old to deploy overseas, would enlist in 1942 and serve as a mountaineering instructor. Paul would enlist in 1944 and fight in Italy, winning a silver medal for his valor. For these men, fighting Hitler and the Nazis was personal.

—-

We’re exploring the state of climbing in America and Europe before the war so that we have a better sense of the uphill battle the 10th Mountain Division would encounter when it began to come together in 1941. By the time the McCowns arrived in the Tetons, Germany already had three full divisions—the Gebirsjagers, or “Mountain Hunters”—trained to fight in cold, mountainous conditions. America’s entire military, meanwhile, consisted of fewer than 200,000 soldiers, none of whom were similarly trained.

When John McCown enlisted in the Army shortly after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, he would not only be joining a brand-new division that had no precedent in American military history; he’d be going up against an enemy with generations of institutional mountain knowledge. That’s a big ask of a young man who, at this point in our story, still hasn’t completed the first proper climb of his life.

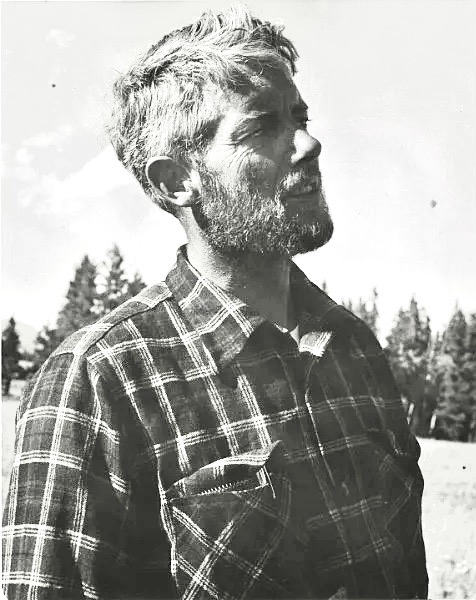

The more I’ve learned about McCown, the more impressed I’ve become. According to the North American Falconers Association, the number of falconers in North America before the war was less than 200. That three-week ski camp in Dartmouth Basin? Nobody went skiing for three weeks, in Dartmouth Basin or anywhere else in the range. They still don’t. At the University of Pennsylvania, he studied at the prestigious Wharton School, and, in addition to his falconry, he played football and lacrosse, was a member of the Varsity Club, Phi Kappa Sigma Fraternity and the Mask and Wig Club, a singing group. Reading between the lines of the brothers’ letters home, he made friends wherever he went, and the Margaret Smiths of the world didn’t seem to mind his company either.

But how much of this is me, romanticizing a man who has been lost to the mists of time? I’ve read his letters, studied photos of and by him, talked to his niece and nephew—but all those things are at best twice removed from the man himself.

Fortunately for us, Howard Koch not only learned to climb with David Brower; he also fought alongside John on Italy’s Riva Ridge.

[Howard Koch Interview]

HK: John McCown was the executive officer of the company I was assigned to when I arrived in Italy. I inherited the weapons platoon there, and McCown assigned me to the weapons platoon and…

CB: Tell me about him. oHw would you describe him to me?

HK: John McCown was a fine gentleman. He was from Philadelphia. And of course I didn’t know many people from the East Coast but he was just a great officer. He was the executive officer of C Company.

CB: Can you describe John McCown to me? What did he look like? How tall was he?

HK: Good looking fellow, good looking guy and he was a fine man. I would say he’s a man of good integrity. And he had been in the American Alpine Club in the Tetons and stuff like that.

CB: What did he look like?

HK: Well, he was taller than me. I was never taller than 5 ’10. He was pretty good size, he was muscular I think —very impressive, impressive to me.

CB: And how would you describe his character?

HK: I think he was probably a man of great integrity. I guess I loved John. I was… he kind of took me in his hands and was very nice to me and always encouraging me. And when you’re a replacement officer, you don’t know anybody in the company. And so I got to know all the guys in the company. And it was wonderful. He’s so nice to me when I came home, I was just a brand new guy and he was just so kind to me.

CB: Did you ever talk about climbing?

HK: I didn’t really know that he had climbed all the Tetons until later, after I knew him a little bit. Yeah.

Wow, Howard. Wow.

It’s both fascinating and frustrating to try to understand the past through the prism of time; the lens of our current day can illuminate certain elements of history while rendering others opaque. The McCown’s letters to their parents provide numerous insights into how their 1939 Teton trip began to shape them into mountaineers, but there are other sections that have left me completely stumped.

As a climbing historian, it’s relatively easy for me to map out the evolution of American mountaineering and John’s place within it before the war. I can also understand the brothers’ budding romance with the Tetons, because I, too, was young when I arrived here, and the awe and trepidation and wonder they express in their letter upon first venturing into the range mirrors my own.

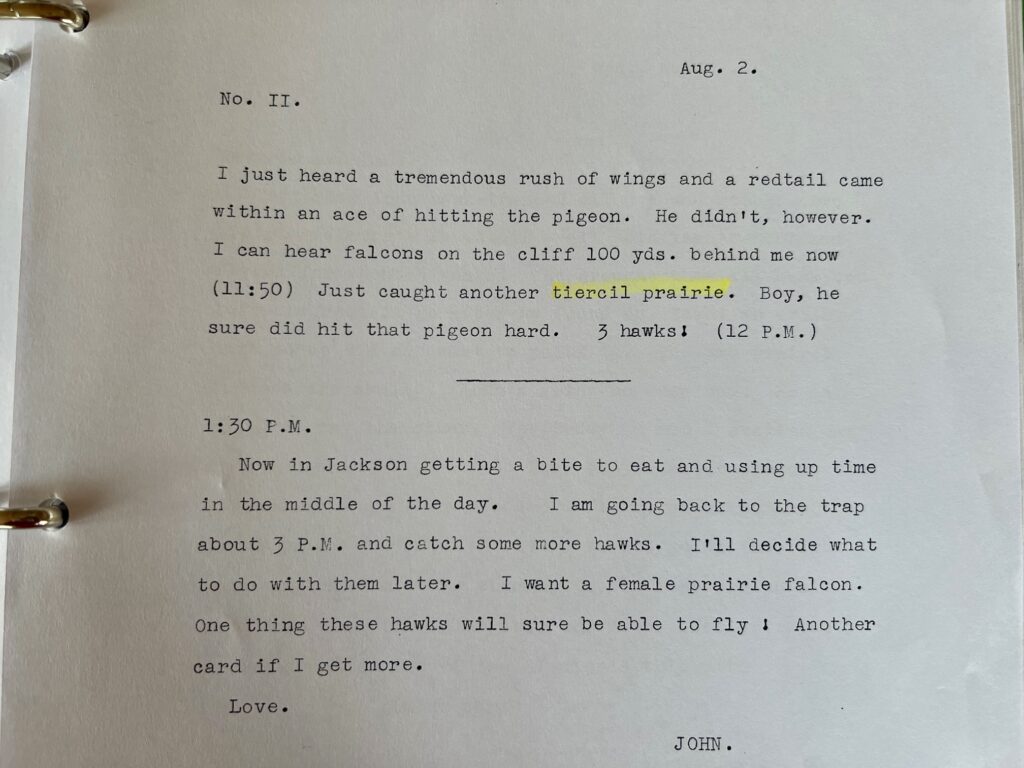

But there’s one thing I know nothing about, and that’s falconry.

In June and July, the brothers’ letters are littered with birds, prairie falcons and redtails and peregrines in particular. Any time they weren’t in the mountains, John was hunting for birds, and driving everyone around him into a hawk craze in the process. He captured prairie falcons from their eyries in cliffs around the valley and brought them to Fred. He gave them to guests at the Bar BC dude ranch and shipped them home to his parents and to his friends and then went out to capture more. To put it frankly, when John McCown arrived in Jackson’s Hole in late June of 1939 with Grove and Ed and his Cooper’s Hawk in the back seat of their Ford Woody Wagon, he had birds on the brain.

And then, on August 2, Joe Hawkes, the ex-marathoner from Chicago that the boys had met at the ski race, asked them to climb the Grand Teton. Grove and Ed, who were exhausted from an unsuccessful attempt on Teewinot that day, said no. John, who’d been out birding instead, said yes. The next day, he and Joe embarked on the mountain’s Exum Ridge without a rope—an event we discussed in the last episode, and one we’ll return to shortly.

In all the letters John wrote home to his parents after he climbed the Grand, there were no more mentions of falconry. All he talked about was climbing.

Because John and his climbing would come to play such an important role in the 10th, I naturally wanted to know more about how it started. And because it was born out of his obsession with falconry, I wanted to know more about that too. What is falconry, anyway? Was it popular in the 1930s? What’s its allure, and why, after John climbed the Grand, did he never mention it again?

I had no idea how to answer such questions. So I called the only person I know who did. Like John, he’d started out as a falconer as a teenager, and he’d come to the Tetons shortly thereafter, where his love of falconry had been displaced by a love of climbing. From there, he’d gone on to pioneer routes from the Tetons to Yosemite to Canada and the Himalaya, and his 1968 trip with Chris Jones to Patagonia gave birth to a company by the same name. His name is Yvon Chouinard.

[Yvon Chouinard interview]

I asked Yvon how he’d explain falconry to someone like me who knew nothing about it.

YC: Well, it’s just a matter of training falcons to hunt for you. Hawks and falcons. So, a hawk is a short-winged bird like goshawks and stuff. And then falcons are like peregrines and kestrels —kestrels are falcons, actually. So, they hunt differently. And so you train them differently. And you can either capture young birds, but then you gotta train them to hunt, or you can trap a wild bird and tame it.

Was it popular in the 1930s?

YC: It wasn’t popular at all. I mean, all the books on falcons go back to, I don’t know, the 17th century. And, I mean, they’re very old. And the Craighead brothers were pretty much responsible for this article they wrote in National Geographic called Hawks in the Hand. That was the first time I’ve heard of anybody popularizing falconry. And the fact that he had a Cooper’s Hawk which is pretty unusual because they’re very hard to keep alive, they’re very high strung and they’re great hunters…. I used to have Cooper’s Hawks. And, you know, if you feed them any kind of wild birds that have any kind of disease, the Cooper will get it. They’re really not resistant to disease very much.

Here’s my most important question. Why, after John climbed the Grand, did he never mention it again?

YC: The big thing about falconry and stuff is that it’s a full-time thing. I mean, you have to dedicate yourself completely to it—you can’t take off for a day, a couple days and go climbing. Somebody has to work with those hawks every single day. Somebody young like that — you can’t become a climber and a falconer at the same time.

CB: So that’s why all of a sudden he stops talking about falconry.

YC: Yeah.

But when, exactly, did he fall in love?

I believe it was about to occur precisely when we left John at the start of our last episode, perched atop a golden nubbin on August 3, 1939, on the Grand’s Exum Ridge, 7,500 feet above the valley floor and forty feet above a bone-shattering ledge, with his partner, Joe Hawkes, nowhere to be seen and a reversal of the delicate moves John has just made out of the question.

I believe John fell in love when he committed.

–

John hugged the mountain. With his arms outstretched for balance, he pressed his right cheek against the rock and gazed at the stone that fell away from him in all directions. Golden swathes of rock were dotted with constellations of black and white mica that twinkled in the sun. He scanned the wall for something, anything, to hold onto. It was like looking through a kaleidoscope. There was nothing.

The rock was painted in bands and belts and mottled patterns of color that reminded him of birds. Inky black stripes stood out against cream-colored stone like a raven against a snowfield. Slate-grey bands ran through the wall, looking for all the world like the dashings on a peregrine’s wings. Braided abstractions of tawny-colored rock reminded him of the dense reddish barring on the breast of his Cooper’s Hawk.

A gentle breeze tickled the sweat on John’s neck. Beads of moisture wet the cotton of his shirt where it pressed against his pack. His belt pinched into the flesh of his hips. He noted it remotely, as distant as the hairs on his calves stirring with the wind.

The rock was warm against his ear. He wondered what it would tell him if it could talk. If he could listen.

When leading, climbers tied into the rope with a bowline on a bight, and carried their gear—pitons, hammer, carabiners—in their pockets.

John’s jacket was in his rucksack. His rope was on the valley floor with Grove. He had no idea where Joe was. He was adrift in an ocean of stone.

Go.

Holding out his arms as if he were hugging the mountain, John leaned slightly to the left and slowly, gently, shifted his right foot up toward the nubbin. With the slightest of hops, he switched feet.

He played the fingers of his right hand up the wall in search of a hold. Still nothing.

Leaving the nubbin was the hardest thing he’d ever done.

In climbing, friction is the art of believing. John rose now by virtue of faith alone. One move after another, he climbed, distributing his weight between the palms of his hands and the soles of his klettershues with a levity that felt surprisingly organic.

Three feet from the nubbin. He levitated another move higher. Four.

There was no doubt, no hesitation, no questions about what to do next. There was simply climbing. John had never experienced a commitment so absolute it transcended thought, and when it happened, the separation between him and the mountain disappeared. As he dropped out of his head and into his body, he shifted from a state of conditionality to one of pure being, and in that moment everything became possible because everything was connected. He began to flow.

And then, there it was: an indentation just big enough for his right hand to grant purchase. He made another move, and a fluted edge appeared for his left, followed by a little divot and a small cupped handhold.

The angle backed off. A belt of harder stone appeared before him. Zebra stripes of compressed gray rock became pronounced with features. A crack appeared, and he sunk his fingers into it with a slow dawning of euphoria.

He was safe.

A minute later he pulled onto a ledge and there was Joe, legs outstretched, sitting with his back against a white-and-gray boulder as wide as a door. Just sitting there, looking out beyond John’s shoulders at the view to the south.

John climbed up beside him, swiveled, and sat down. As the pounding in his chest began to subside, he gazed out at the bands of gneiss that formed undulating stripes throughout the range. The summit of the South and Middle Tetons that he’d stood on with Grove and Ed a week earlier now lay at his feet. The summer had melted away the remnants of winter; the only significant bit of ice that remained was the Middle Teton glacier. The high basins to the west still held pools of green, but the tawny brown of Jackson’s Hole to the east was now the same color as the rock.

Across the canyon, the twin couloirs on Nez Perce met in a V at the base. Cloudveil Dome buttressed the upper reaches of the canyon’s southern fork. The pointed summits of Gilkey’s Tower and Spaulding and the Ice Cream Cone marched with military precision toward the broad summit massif of the South Teton. Snowfields crouched in its shadow, hiding from the sun.

“Sure is pretty,” Joe said.

John didn’t say anything. He just let the Tetons keep rolling toward him, too vast and complicated to comprehend.

[line break]

And that concludes Episode 2 Part 2 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening. If you liked the episode, please subscribe to the podcast, and share it, tell a friend about it and give it five stars on your app. Sign up for our newsletter at christianbeckwith.com so you don’t miss an update, and while you’re there check out the episode’s additional content, including bios for all the new characters we introduced today.

Special thanks today go out to our new patrons, Ted Cartner, Lance Blyth, Denise Johnson, Karen LaNoue, Colleen Monahan, Greg Kerwin, Howard Lukens, Val Rios, Clint Steele and Ted Shred.

Patrons are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack because they make it possible to keep the show going. I hope you’ll consider becoming one too.

We’re excited to welcome The 10th Mountain Division Descendants and the Denver Public Library as our partners in the podcast. Special thanks go out as well to our advisory board members, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt, for their help with this episode Thanks to Chris Jones, Howard Koch and Yvon Chouinard for their contributions, and to Denise Taylor for connecting me to Mr. Koch, and as always props to Francisco Diaz for his help in putting this episode together.

Until next time, thanks for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.