Available only to our community of patrons, this Unabridged version of Episode 4 takes a deep dive into the US Army’s experimental ski patrols of 1940-1941, and the events that led to the activation of the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry at Ft. Lewis, Washington—the unit that would eventually become the 10th Mountain Division.

The episode also explores John McCown’s 1941 expedition to British Columbia’s Coast Range, which he made before enlisting with the mountain troops, and features an interview with writer Will Holland, who has been working on a screenplay about McCown for over two decades.

This Unabridged version includes:

- Photos and historic images that illustrate the episode

- A complete chronology of events from the episode, leading up to the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into World War II

- A detailed synopsis of the experimental ski patrols, including key dates and links to newspaper articles

- A complete transcription of the episode

See here for an overview of the characters introduced in this episode.

Episode 4: The Ski Patrols

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and I’m so glad you’re joining us here today, because at long last we’ve reached an important milestone in our story of the 10th Mountain Division: the start! Today we’ll be exploring the US Army’s experimental ski patrols of 1940-1941, and the activation the following winter of the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry at Ft. Lewis, Washington—the unit that would later evolve into the 10th Mountain Division.

For those of you just tuning in, we’ve been exploring the Division’s genesis, starting with Russia’s late 1939 invasion of Finland, the Finns’ successful resistance during the so-called “Winter War,” and the way they inspired America’s climbers and skiers to lobby the United States War Department for a mountain unit of our own. We’ve done a deep dive into the roots of climbing and skiing in America, and in our last episode we explored the history of Germany’s mountain troops, the resistance an American mountain division faced from within the US military as well as how the rise of the Third Reich caused some of the world’s best climbers and skiers to immigrate to America from Germany and Austria. Along the way, we’ve been recounting the story of John Andrew McCown II, a young man from Philadelphia who learned to climb in the Tetons in 1939 and who would later go on to become one of the 10th’s greatest unsung heroes.

This podcast is part of the real-time research for a book I’m writing about John McCown, the 10th and its influence on American outdoor recreation. We couldn’t do the show without our partners: The Tenth Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the American Alpine Club and The Tenth Mountain Division Descendants. We also can’t do it without you.

Ninety-Pound Rucksack is made possible by our community of patrons. If you’d like to help support the show, please go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. For $5 month you’ll get extended and exclusive interviews, as well as bonus content like historic photos and full transcripts from each and every episode.

While you’re there you can sign up for the newsletter so you never miss an update. And if you like the show, give it a five stars on whatever app you’re using to listen to it, tell your friends about it and help us to keep it all going.

And now, let’s catch up with our hero, John McCown, whose alpine education is about to accelerate in one of the most rugged and remote ranges in North America.

—

July 6, 1941. A blinding, white-hot flash of pain shot up from John’s ankle. He had been making his way tediously through the crisscrossed windrows of burnt timber that littered the valley floor when he’d slipped off a wet branch and plunged to his knee in a hidden sump hole. Momentum had carried him forward and his 85-pound pack had done the rest, slamming him sideways to the ground, where he now lay writhing in pain.

John and his best friend Ed McNeill were nine days into their approach into British Columbia’s Coast Range, the legendary home of Mt. Waddington, a snow and ice and gunmetal gray granite fortress of a peak so wild and remote it had thwarted sixteen attempts by the continent’s best alpinists before it was finally climbed. Guarded by a phalanx of similarly sharp and formidable rime-coated towers, ringed by vast glaciers on every side, the mountain lay hidden deep in the heart of the range, cloaked in perpetual snows and protected by steep-sided valleys and fast-moving rivers and long thin lakes haunted by the ghosts of submerged trees.

Had it been audacious of John and Ed to think they were ready for an expedition of this magnitude? Absolutely. Neither of them had ever been this far from civilization. Hell, the only real mountains they’d ever been in before were the Tetons, where just about everything could be climbed in a day from the valley floor. This was interior BC. Just getting to a point where they could see the mountains—when you could see them, given the perpetual rain—meant navigating labrynths of alders and poplars and willows and the medieval spines of the aptly named Devils Club. But they were twenty-three, the both of them, with two solid years of Teton climbing under their belts, recently liberated from college and yearning for adventure—and what better one could there be than amidst the mythical Coast Range, attempting mountains that had yet to be drawn on any map?

John’s induction into The American Alpine Club the winter before had introduced him to climbers like Bob Bates and H. Adams Carter and Bill House, young men not much older than himself who nonetheless dreamed up expeditions bigger than anything he’d ever imagined possible. Their ascents of peaks in Alaska, the Yukon and the Himalaya were historic. House’s account of his and Fritz Wiessner’s first ascent of Waddington in the 1937 American Alpine Journal had been as breathtakingly bold as the climb itself—a climb made possible only by the exceptional climbing skills Weissner had honed in Germany before fleeing Hitler’s rise.

John wanted that kind of boldness for himself: complete self-reliance, no margin for error, dependent on just one other person for success and safety alike. He wanted to carry mammoth packs for weeks on end until his body hardened into tightly knotted muscle and the wilderness wiped the anxieties of the world from his mind. John was set to begin law school at the University of Virginia in the fall, and America would soon be at war, that much was sure, and he wanted nothing more than to drop out of school before he even got to Charlottesville and join the mountain troops Bates and Carter and House were helping to start. But before then, one last rip-roaring adventure, as big as they could dream up, just him and Ed, hunting game on the approach amidst a landscape so awesome and precipitous it crowded out the din of his father’s expectations and his brother’s death and a career he was pretty sure he didn’t even want.

The timber-strewn Homathko River, which they had planned to descend most of the way to Waddington, had wrecked their canoe on the very first day. They’d piled their dried rations and clothing and camping gear and climbing equipment and movie camera and high-powered rifle onto and into their yukon pack frames and staggered on, making six to eight miles a day to start before the fallen timber and swampy thickets had slowed their progress to a crawl. The much-anticipated deer and moose and mountain goats they’d counted on for food had failed to materialize. They’d wanted an adventure. Now, as John lay like an upside-down turtle in murkwater, weeks from help, pinned by his pack between two downed trees and clutching his ankle while the fast-moving storm clouds enveloped the rocky ridges thousands of feet above him, he realized, quite coolly, the adventure had just begun.

—

Ah, but we are getting ahead of ourselves, aren’t we? Let’s backtrack eight months, to the end of 1940, when, in no small part thanks to the interventions of Lietuenant Colonels Nelson Walker and Charles Hurdis, the National Ski Patrol System had taken possession of a new office in the Graybar Building of midtown Manhattan from which to advise the Army on matters of training and equipping soldiers while it solicited recruits. At the same time, The American Alpine Club had set up its National Defence Committee to assist the Army with considerations related to mountain warfare. Never before had civilian organizations partnered directly with the United States military to develop its forces—but never before had the military been up against the sort of existential challenges posed by Hitler and the Nazis.

[Radio broadcast] Christmas day began in London nearly an hour ago. The church bells did not ring this morning. When they ring again, it’ll be to announce invasion. This is not a merry Christmas in London. I’ve heard that phrase only twice in the last three days. This afternoon as the stores were closing and shoppers and office workers were hurrying home, one heard such praises as, “So long, Mamie, and, “Good luck, Jack”—but never a “Merry Christmas.“

If you were General George C. Marshall or Secretary of War Henry Stimson, and Hitler continued to bomb the hell out of England and steamroll his way across Europe while your own war planners told you the only way to contain him was to expand your army from 200,000 soldiers and 8 divisions to 8.8 million soldiers and 215 divisions in three years—an endeavor orders of magnitude more complicated and ambitious than anything the country had ever undertaken—and one tiny piece of that expansion included the creation of a mountain division for which there was neither precedent nor roadmap in a county with almost no tradition of mountaineering, and all of the heretofore mentioned matters were occurring amid a global conflict that seemed increasingly certain to pull you in, how and where would you start?

Desperation, they say, is the mother of invention, and whether or not you believe the circumstances qualified as desperate, they certainly added a degree of urgency to the War Department’s considerations. On December 5, 1940, as the woefully unprepared Italian Army continued to drop from bullet and cold alike in the mountains of Albania, Marshall and Simpson sent out their directive: six divisions of the United States Army, all located in the country’s so-called “snow belt,” would put together experimental ski patrols and teach soldiers how to ski, snowshoe, camp and travel in snow and high mountains. Each of the units were to be given $1,200 to purchase winter equipment locally, test it for military use and report back on what they found. The Army’s next foray into cold weather and mountain warfare had begun.

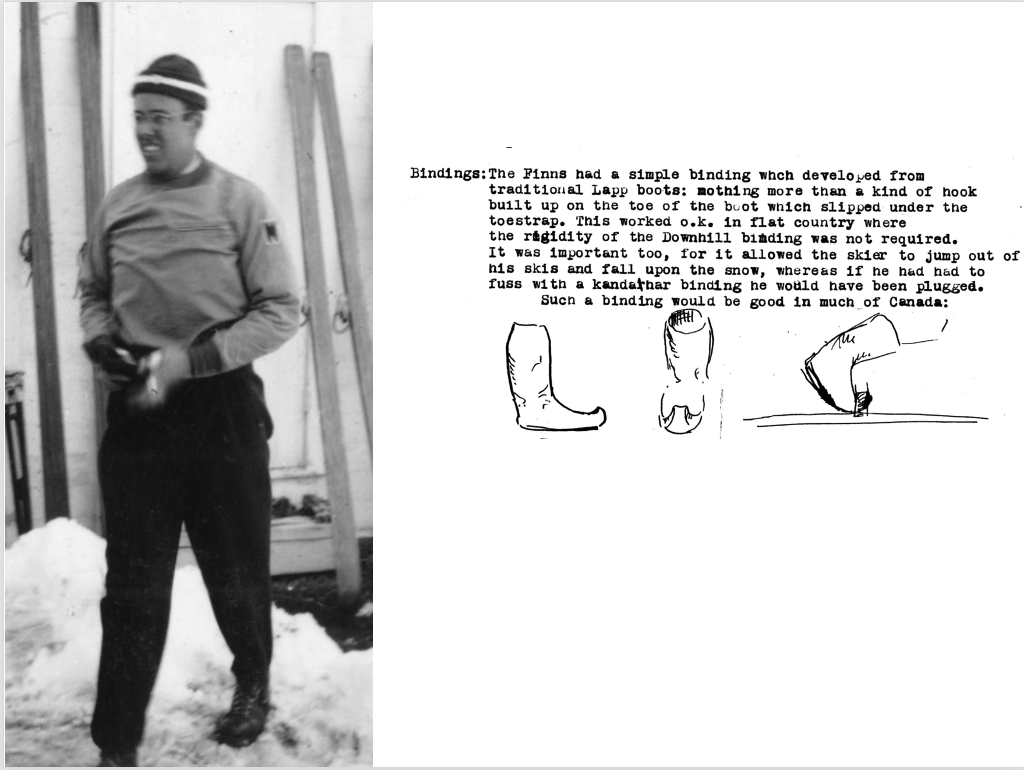

The challenges started almost immediately. Though the National Ski Patrol System had been directed to provide the military with a list of equipment it would need for the ski patrols, and to identify the manufacturers from whom to buy it, it soon ran up against the Army’s byzantine manner of doing business.

Take bindings, for example. To a skier like Minnie Dole, the matter was simple. “The very basis of any maneuvers on skis is the ability of the skier to transmit brain reaction to his foot and toes,” he wrote to General Marshall. “His foot must be so attached to his skis that the muscular reaction … will be transferred to the full length of the ski from tip to heel.” The obvious choice, at least to Dole, was the cable binding, which could be found attaching feet to skis on slopes around the country.

The War Department’s rationale was driven by other considerations. The Army needed battalions of soldiers who could ski cross-country for miles in deep snow, then take their skis off and fight—and they needed them now. A simple leather-strap binding—one like the Finns had used, that would keep the standard Army-issue boot, encased in the standard Army-issue overshoe, adhered to the ski—would suffice. Dole’s frustration was absolute.

The task of explaining to Dole how the Army worked fell to Lieutenant Colonel Walker—or ”Johnny” Walker, as he was perhaps inevitably known. “With reference to equipping the battalions for elementary training with skis having only a simple strap binding, you are entirely correct that this is a poor substitute for the proper equipment,” he wrote to Dole. “The War Department’s decision in this matter is necessarily based, not upon what is desirable, but what is practicable. To purchase a good quality binding involves the test for determination of type, the advertisement for competitive bids and the formulation of complicated contracts…. The same thing … holds true for ski boots with the additional complication of tariff sizes.”

Walker then coached Dole through the grey areas in military bureucracy where things actually got done. “We can, however, secure skis with a simple strap binding in a single contract without much hocus-pocus,” he wrote. “As soon as we can procure proper bindings and boots in quantity, we can throw away the strap bindings and put the better binding on the same pair of skis.”

Think of everything you’d need for a good winter adventure in the hills: skis and boots and bindings, yes, and also packs and clothing and tents and sleeping bags and sleeping pads and food and stoves with which to cook the food. Now add in tests for determination of type, competitive bids and the formulations of complicated contracts and you begin to understand what civilian climbers and skiers like Dole were up against.

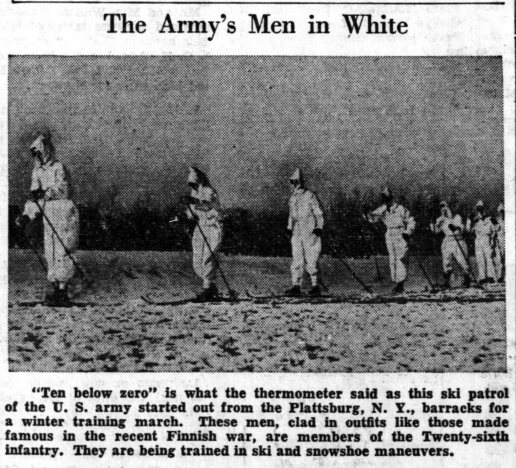

As 1940 neared its end, detachments of soldiers and officers fanned out across the country and, properly equipped or otherwise, prepared to learn how to ski. The First United States Army, in charge of the northeastern part of the country, had a head start: the winter before, as you’ll recall from Episode 1, it had conducted the first large-scale winter maneuvers in American military history, sending some 1,000 soldiers from its 28th Infantry Regiment to train at New York’s Pine Camp and at Lake Placid. Now, in the middle of December, it began sending small weekly detachments from its 26th Infantry Regiment to refine their skills under the guidance of the same person who’d trained the troops at Lake Placid the year before: a 41-year-old Norwegian American named Rolfe Monsen.

American skiing was a decade removed from its earliest chapter, when cross-country skiing and ski jumping had dominated the scene, and the Norwegian-born Monsen was one of that chapter’s brightest stars. His role in our story is relatively minor, so you don’t need to remember his name, but remember this: he was among the first of the truly famous skiers and climbers who would serve with the mountain troops, and who would go on to make the 10th Mountain Division a household name.

Like most Scandinavians, Monsen had learned to ski and walk at roughly the same time, and he’d learned to fight on skis as a soldier in the Norwegian army. In the fifteen years since he’d emigrated to the US, his mastery of cross-country skiing and ski jumping had been on prominent display as he’d racked up win after win across the country. In 1927, the year he became an American citizen, he won every competition he entered.

Monsen’s talents had landed him on not one, not two, but three US Olympic ski teams. At the 1928 Winter Olympics in St. Moritz he placed well in cross country and better in ski jumping. Four years later, at the 1932 Winter Olympics at Lake Placid, he’d placed ninth in the Nordic Combined, the best showing ever by an American. Four years after that, when an injury prevented him from competing in Germany’s Winter Games at Garmisch-Partenkirchen, his teammates chose him to bear the American flag at the Opening Ceremonies instead.

If you’re a soldier in the Army who has to learn to ski, you could do worse than learn from a three-time Olympian, particularly one as good-natured and affable as Monsen. Once a week, from December 16 to February 27, ten officers and a hundred enlisted men traveled to Lake Placid to learn to ski and snowshoe under Monsen’s guidance. He led scouting patrols over all types of terrain, in all types of weather, amidst the Adirondack high peaks and on the flanks of Whiteface Mountain. He instructed troops to ski while wearing packs and carrying rifles and side arms. He taught them to climb steep slopes, drop, fire, rise and disappear downhill on skis.

By early February, more than 700 members of the regiment had cycled through Monsen’s trainings, and a sub-unit of three officers and 53 enlisted soldiers had been selected for even more exacting instruction. But it wasn’t just skiing the soldiers had to learn. They also had to figure out how to move the artillery necessary to fight a war in winter. They mounted anti-tank guns on skis and machine guns on sleds and toboggans and moved them with dogsled teams. They pulled an anti-tank gun on a new-fangled device called a snowmobile that could speed over frozen surfaces at up 70 miles per hour. Like everything else about a mountain unit, the instruction manual for such transport had yet to be written, and trial and error ensued.

The local papers covered the proceedings on a weekly basis with growing fascination. Hitler was winning, and the country’s involvement in the war seemed ever-more inevitable. Americans needed a diversion to take the edge off—and the soldiers on skis fit the bill.

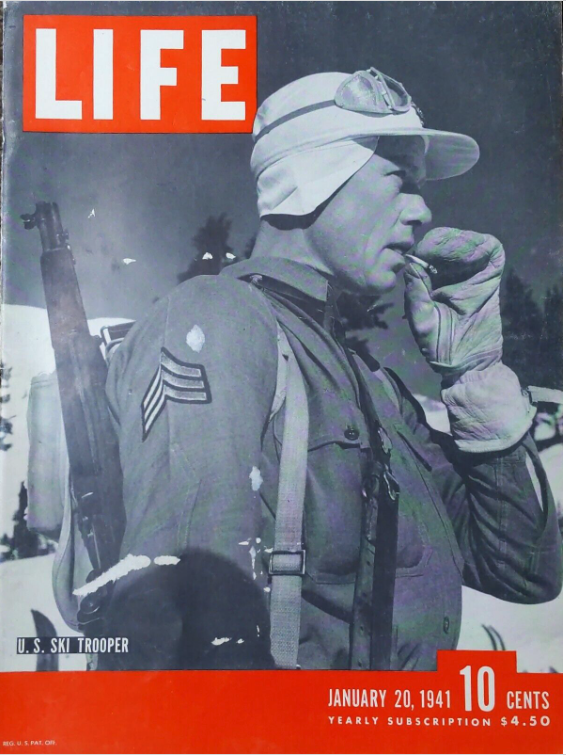

In January 1941, Life, the most popular magazine in the country, put a photo of a ski trooper from one of the winter’s ski patrols on its cover. Rifle slung over his shoulder and his glacier glasses perched atop his white-brimmed hat, the soldier stared stoicly into the distance while taking a drag on his cigarette. The image said it all: patriotism and rugged masculinity had converged with America’s winter warriors, and their fame began to grow.

Lake Placid was all in. In mid-February, the Chamber of Commerce made a bid for an expansion of the soldiers’ training the following winter with a movie of, as the local paper called it, “white-clad doughboys gliding over waist-deep snow at speeds of up to 20 miles per hour” and pitched it to the War Department in DC. In a practice that quickly won over the hearts of the Lake Placid community, they lowered the flag at the Olympic stadium every afternoon at 4 p.m., standing at attention during the sounding of retreat in camoflauged outfits similar to those used by the Finns.

By the time lack of snow brought Monsen’s trainings to an end on February 28, 1941, some 1,200 soldiers and officers had passed through his classes. He was as proud as a parent: the troops, he noted, had proved to be good pupils, ones who would be able to execute their military orders effectively. Perhaps more important, he deemed the one-week training periods sufficiently intensive to create a soldier on skis.

The unit’s commanding officer, Colonel James Muir, reached a similar conclusion. Any young man, as he put it, “of good physique, particularly those with a well-coordinated sense of balance, can become expert on skis in a relatively short time.” Arming, equipping, evacuating and moving the troops was another matter—but even so, he deemed the development of winter soldiers worth the effort. “I believe that ski training is an asset,” he remarked. “Like the Texan’s six-shooter, you may not need it, but if you ever do, you will need it in a hurry, ‘awful bad.’”

Monsen wasn’t the only Norwegian training troops that winter. For that matter, he wasn’t even the only Norwegian-born Olympian.

Less than a hundred miles away, Harald Sorensen, who, like Monsen, enjoys but a brief appearance in our story, was also working on behalf of the Army.

Eight years Monsen’s junior, Sorensen had won countless competitions throughout Scandinavia while growing up in Norway. After he emigrated to the US in 1929, he thrilled millions in both North America and Europe with his cross-country and ski jumping performances. He’d been selected to join Monsen at the 1936 Olympic Games in Germany only to have his dreams dashed by incomplete citizenship papers.

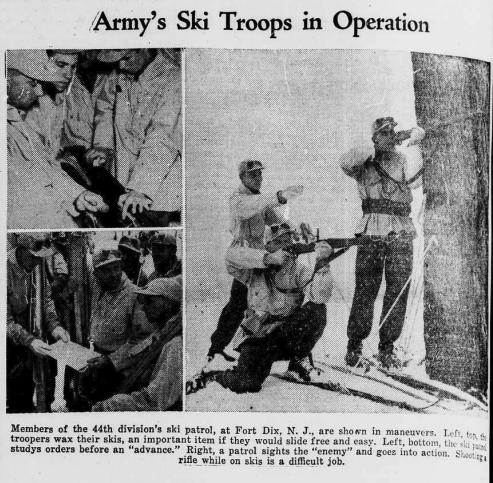

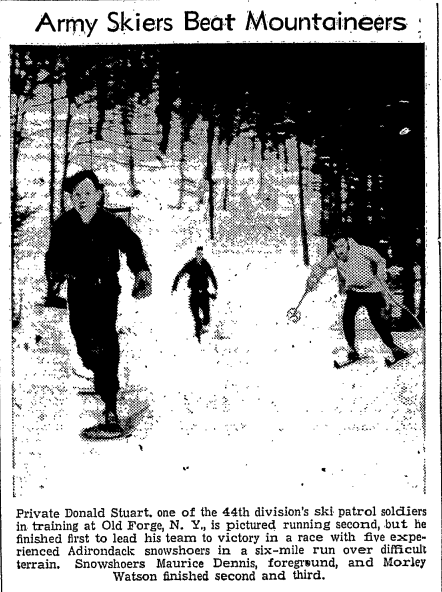

In February, a few days after he’d been inducted into the Army, Sorensen went to work coaching 33 men from the 44th Division in the Adirondack mountains around Old Forge, N.Y. Basing out of an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp, the patrol trained by day and moonlight, in good and bad weather, testing various types of sleeping bags, clothing, skis, and winter equipment along the way. Sorensen and his team drilled the soldiers in cross-country, slalom, downhill, and formation skiing, orientation and patrol tactics, close and distance reconnaissance, night raids and ambushes on “hostile” groups until they could travel up to 25 miles a day with 45-pound packs and be ready for combat on arrival.

As they had in Lake Placid, the papers caught wind of the exercises, and reported on the manouevers week after week. By the middle of February, the local woodsmen had had a gut of it. They knew these mountains better than anyone, and they knew for damn sure snowshoes were the way to go. Down went the gauntlet (or mitten, as the case might have been): four native snowshoers, the best in the Adirondacks, against four skiers from the 44th, in two five-mile races, primarily uphill, through heavily forested terrain, on courses laid out by the snowshoers themselves.

The 44th accepted the challenge, and their skiers won with ease. The Army took note: while snowshoes, not to mention mules, would remain indispensible for heavy loads, skis were quicker.

Small insights like these began to illuminate the Army’s understanding of winter warfare.

In the winter of 1940-1941, the most up-to-date manual on cold weather fighting was the War Department’s August 1914 “Alaskan Equipment, Revised Edition” Winter Warfare File. When thirty-two-year-old Albert Jackman reported for duty in the fall of 1940, a captain handed him the file. It “consisted of one folder about ¼ inch thick,” Jackman would later recall. “So far as I can remember, there was no special clothing. The entire army was issued wool underwear…, wool socks, wool shirts, wool trousers…, leather high shoes with or without hobnails, a high collar wool blouse of the same material as the breeches, and a long heavy wool overcoat. A cap with earflaps was worn when it was too cold for the campaign hat. Gloves, scarves, [and] sweaters were usually not issued… .”

A cheerful, straight-shooting man with angular features and a lean physique, Jackman hailed from Kansas, a state the high point of which, the 4,039-foot Mount Sunflower, sits less than half a mile from the lowest point in neighboring Colorado. He’d moved to New Jersey in 1924 to attend prep school. Three years later, he’d enrolled in Princeton, and, as the country had moved from the Roaring Twenties into the economic calamity of the Great Depression, he joined the Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). He became a member of Princeton’s pistol and rifle teams, and, by the time of his 1931 graduation, as America was entering the nadir of its financial hardship, was a commissioned Second Lieutenant in the Reserve Corps’ Field Artillery.

For the next ten years, Jackman sold life insurance by day, but his heart was in the mountains. He became an active member of the Potomac Appalachian Trail Club and the Ski Club of Washington and climbed, skied, and camped in winter. He also maintained his Reserve Commission, and in December 1940, now a Captain, he was assigned to the 5th Division’s ski patrols in Camp McCoy, Wisconsin.

These patrols were the most concentrated of any the Army put together that winter. Accordingly, on December 8, 1940, it set up a Winter Warfare Training Board to study and test the clothing and equipment used by the troops. Jackman became the Board’s director, observing a large detachment of a thousand soldiers and a smaller, more specialized detachment of 250 as they learned to ski. While they trained, Jackman took notes.

His assignment was to study the gear, but he also observed the soldiers’ experiences. “[T]his battalion is like nothing seen in the army since the spring thaw at Valley Forge,” he wrote his fellow reserve officers. The morale, he noted, was good, mainly because the soldiers loved the skiing.

The larger detachment used basic equipment for it manoevers. The more specialized Ski Patrol got the best civilian equipment money could buy. “The Patrol is the pampered baby,” Jackman wrote. “They can have anything they want, and their procurement officer just goes out and buys it.”

Jackman observed both throughout the winter,, recording specifics until he’d assembled a detailed report. It would go on to play a major role in the Army’s planning—as would Jackman.

If you were a soldier in search of a true big-mountain experience, though, and you got your pick of places to train, you couldn’t have done better than Washington’s Fort Lewis. Though the Tacoma base isn’t exactly an alpine mecca, it nonetheless boasts views, on rare clear days, of Mount Rainier, a fourteen-thousand-foot peak sixty miles to the southeast that towers 8,000 feet above its surroundings.

Rainier is massive, a sprawling, active volcano that creates its own weather. With 25 named glaciers, it’s home to the largest glacial system in the lower 48. From above, the mountain looks like a white octopus with a prominent depression in its head and two dozen tentacles extending in 360 degrees from its body. Its proximity to the Pacific means that it’s wet, and its altitude means it’s cold—not the dry cold of the Rocky Mountains, which can make zero degrees on a sunny, windless day feel comfortable, but a wet cold that works its way through layers to chill one’s very bones.

Deep, steep-sided valleys, wild winds above treeline, heavily crevassed glaciers and more than fifty feet of snow a year make it a rugged place to learn to ski, and the perfect place for the Army to begin testing its troops.

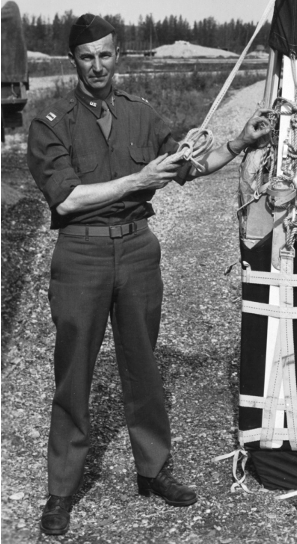

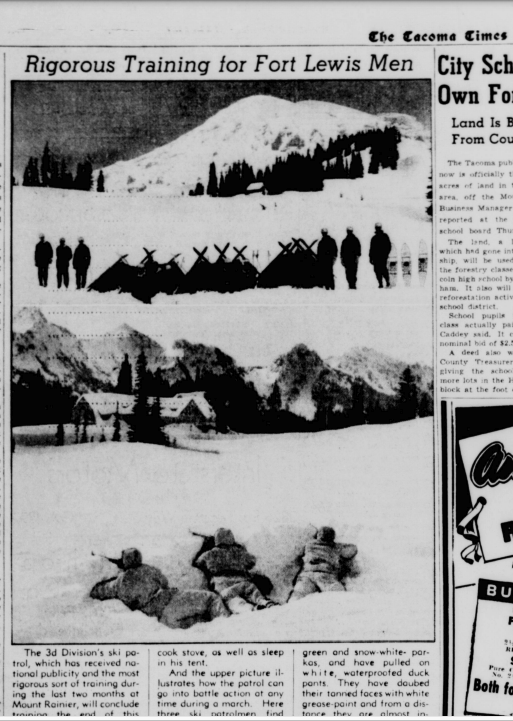

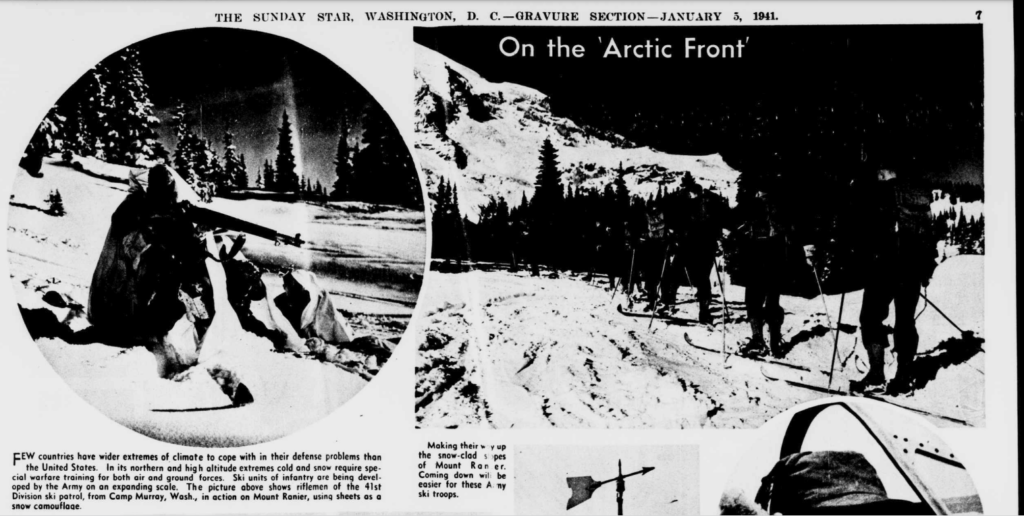

The Army created not one but two experimental ski patrols to operate on Rainier’s flanks. The 3rd Division ski patrol consisted of two officers and 22 enlisted soldiers, all picked from volunteers from the 15th Infantry Regiment, an active-duty unit based out of Ft. Lewis. The 41st, a National Guard unit out of Spokane, selected its twenty-six-man ski patrol—one officer, twenty-five enlisted—from a group of 150 volunteers. Central to, and the only person to serve in both, was a Seattle local named Johnny Woodward.

Like Monsen and Sorensen, Woodward was the day’s functional equivalent of media click bait. In the northwest, he was synonymous with skiing, and his skiing was synonymous with winning. Local races, regional races, collegiate races: he dominated any competition he entered.

Though renowned for his downhill and slalom skiing prowess, Woodward had learned the Scandinavian specialities of cross-country, ski jumping and telemark skiing from Norwegians at the Seattle Ski Club Lodge, and, like Sorensen, he’d qualified for the 1936 Olympics only to have his Olympic dreams thwarted by the University of Washington, which was not interested in sponsoring his long trip to Europe during the academic year.

Instead, Woodward finished his studies, graduating with degrees in economics and business and dipping his ski boot in the still-nascent ski industry by running a couple of University-affiliated ski shops. He’d also earned a second lieutenant commission from the university’s Reserve Officer Training Corps while ski racing up and down the west coast. By the time he got out of school, he was the most decorated skier Seattle had ever produced—and, given his military training and northwestern skiing chops, the perfect person to help stand up the ski patrols on Mt. Rainier.

Woodward was called up as a reserve officer with the 3rd Division ski patrol on December 1st. On December 9, the patrol moved into a converted Park Service garage near the southern boundary of Mount Rainier National Park. The papers treated it like a debutante getting ready for her ball. “Ski Patrol of 3d Division Begins Tactical Work Jan 2,” announced the Tacoma Times in the middle of December. “John Woodward is expected to join soon.”

The patrol’s technical advisor was Captain Paul B. Lafferty, a thirty-year-old saxophone-playing swimmer from the University of Oregon who had amassed cowboy and ski mountaineering experience en route to joining the Army. Woodward was the unit’s ski instructor. Both were suited to the job, but the twenty-five-year-old Woodward in particular had found his calling, and the local media had found their muse.

What was special about the Washington patrols was the state’s proper mountains and the extended time the patrols spent training in them. And this training brought to the fore a central consideration for the development of a unit that would fight on skis.

As we discussed in Episode 2, American skiing in the late 1920s and early 1930s had pivoted from its Norwegian cross-country and ski jumping roots to the faster, sexier, more glamorous pursuits of downhill and slalom skiing. Central to those disciplines was the Arlberg technique, the progressive system of skiing developed in Austria by Hannes Schneider that had taken the world by storm.

The Arlberg technique looked and worked great on the ski-area slope: the Stem Christiana, one of its cornerstone skills, had an exaggerated, swoopy shoulder swing to it that rotated the upper body a full 100° in the act of a turn. But with a heavy pack, the problem was that swoopy swing: it threw a skier off balance.

The standard-issue semi-automatic rifle for infantrymen in 1940 was the M1 Garand, a .30 caliber weapon that General George Patton, Jr. called “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” It was highly accurate, but its beauty lay in its simplicity: it was easy to assemble and disassemble in the field—the trigger group, for example, could be removed and replaced with the point of a bullet. More important to those who had to carry it, the 43-inch weapon weighed less than ten pounds.

The standard-issue light machine gun was the gas-operated Browning Automatic Rifle, or BAR. Forty-seven inches long, it could fire up to 650 rounds per minute from the shoulder, the waist or mounted on a bipod. It weighed twice as much as the M1—more if one carried it with its three-pound bipod attached.

As any climber or ski mountaineer will tell you, light is right. The heavier one’s load, the slower one goes, and the more energy it takes to get where one is going. And when that weight juts up and out instead of riding close to the small of one’s back, any shifts in momentum torque one’s center of gravity, which, as John McCown could tell you, will spin you out of balance.

For the sort of skiing the military wanted, the styles in vogue on the slopes of America’s ski areas weren’t going to cut it. Instead, the Army needed a technique that would quiet the upper body and lower a soldier’s center of gravity by positioning him in even more of a crouch than that advised by Schneider, where he was less likely to be tossed ass over teakettle by the momentum of his own turn.

Right man, right time, right job. With his mastery of both cross-country and downhill skiing, Woodward was uniquely positioned to morph the civilian style into something more applicable to the Army’s needs. The patrols of the northwest offered a place to start—and the resulting modifications to the Arlberg technique would lead, over the course of the next few winters, to the form of skiing modern practitioners take for granted.

After spending the first six weeks dialing the 3rd Division ski patrol in the basics—uphill, downhill, orienteering, camouflage discipline—Woodward began to teach them to march.

A simple overnight trip was followed by extended outings. Though the soldiers couldn’t bear loaded weapons while in the Park, they carried dehydrated foods, Primus stoves, sleeping bags and light-weight tents, learning as they went. The longer the trip, the more food and fuel they had to carry, and the stronger they became as a result.

In the middle of February, Woodward led twelve members of the patrol on a five-day mission with thirty-five-pound packs and food rations of a pound per person per day. A week later the patrol finished up its training with a 55-mile, seven-day trip that navigated Rainier’s glaciers as it made its way around its flanks. As the Tacoma Times put it, “The jaunt, via Sunrise Lodge and Yakima park, would be impossible, it is believed, except to men in superb physical condition.” Woodward’s job with the 3rd Division ski patrol had ended, but his role with the 41st Division ski patrol was about to start.

The men picked for the 41st ski patrol had little previous skiing experience but, as the papers loved to report, possessed “ample athletic ability” and a “general ruggedness” that left the journalists breathless. “The 41st Infantry Division has a highly publicized ski patrol,” gushed the Dec. 6, 1940 edition of the Tacoma Times, “but its members, civilian skiers will be glad to know, are not ‘fair-weather boys.’” Their mission was to cover great distances over snow safely with the greatest possible speed, carrying their own food, supplies, and weapons along the way, in an effort to determine the effectiveness of the training program. “Effort will be made to condition the patrol to operate in any and all types of weather,” the Tacoma Times reported, “and to stand sustained operations.” They practiced in cold, in wind, in rain. They rose at 5:30, ate, performed their military duties, and then trained on skis and snowshoes from 8 a.m. until 4 p.m. with half an hour’s lunchbreak each day. In addition to the standard ski gear and clothing, each man was equipped with a rifle, bayonet and cartirdge belt, as well as a shovel, mess kit, tent, blankets and extra clothing. “No training in any other branch of the service is more rigorous than that planned by the ski patrol,” the papers proclaimed—and they very well might have been right. By the time Woodward joined them, the 41st had already executed several five-day manouevers that had begun to whip them into mountain shape.

When Woodward took command, the unit moved west, from Rainier to the Olympic Peninsula, and embarked on a 45-mile, west-to-east crossing of the Olympic Mountains through deep snows, up and over peaks and passes and through heavily forested areas with full packs. Men and equipment fared well.

Next came a fourteen-day trip across the wildly remote northern end of the Olympics. The first week unfolded without incident as the soldiers, carrying fifty-five pound packs, averaged ten miles per day, but as boots and bindings fell apart and blisters and exhaustion set in, the strain began to tell. Eight of the group were sent back. The rest persevered, continuing for another week to complete the trip. On April 20, mission accomplished, the 41st Division ski patrol was disbanded.

The ski patrols in general, and the Washington ski patrols in particular, helped the Army understand a number of key points. Snowshoeing was a snap. If a soldier was capable of walking in a straight line on snow-covered ground without falling over, he could learn to snowshoe in thirty minutes. Skiing was harder, but fit young men could learn the fundamentals, as Monsen had demonstrated, in a week, and with two months’ training a soldier could become proficient enough to instruct others.

But it was not enough for a soldier to be proficient on skis and snowshoes. He had to carry heavy loads for extended periods of time, and he had to learn a specific style of skiing that allowed him to do so without tipping over in the middle of a turn. He had to master winter camping and orienteering. He had to understand how to navigate avalanche-prone and crevassed slopes safely and efficiently. He had to eat to keep from bonking and drink to avoid dehydration, even when he didn’t want to do either . He had to keep his feet dry so he didn’t get trenchfoot, regulate his warmth so he didn’t overheat or get hypothermic, wear glacier glasses so he didn’t go snowblind and sunblock so he didn’t turn into a blistered mess.

In the mountains, in both winter and summer, the consequences of something going wrong are compounded by the weather and proximity to safety. If one tweaks an ankle or breaks a binding an hour from camp in a shallow snowpack on a windless, sunny, thirty-degree day, chances are pretty good he’ll make it home for dinner. Increase the snow depth, drop the temperature, kick up the wind, lower the visibility, add weight to his pack and move him further from base, and, as the Italians fighting for their lives in the mountains of Albania could tell you, the chances of a bad outcome go up. A competent winter soldier needed to be able to move through cold and mountainous terrain for days on end fully loaded, and that meant learning how to be self-reliant in all conditions. In short, he had to become a mountaineer.

The experimental ski patrols shed light on what little the military knew and much that it did not. Take food, for example: the patrols had tinkered with proportions and varieties to arrive at a standard ration for mountain travel: cereal, dried potatoes, chipped beef, powdered eggs, spaghetti, a pound and a half per person per day. By the time the 10th finished training three years later, it would see its proportions increased by 40%, to two and a half pounds per person per day. Or take boots: those advertised in the front pages of the American Ski Annual were built for lift-serviced, downhill skiing, but the Army needed boots that were warm, and comfortable, ones that could hike and climb as well as ski and do so for months on end. And in 1941, such boots simply didn’t exist in America.

Still, as militarian historians put it, “by the end of April 1941, the United States Army had ample data … from which to conduct future operations. Not all the information was favorable… but all in all, the path towards activation of official mountain units…, however rough, appeared passable.”

Except when it didn’t.

In late November, 1940, the American Mountain Warfare Research Institute at the Library of Congress, which billed itself as “the most productive source of inside information on the international standards of military mountaineering and winter warfare,” wrote a thirteen-page letter to Minnie Dole pledging their support for his efforts, outlining their own advocacy—and excoriating resistance to a mountain unit from within the military itself.

“In spite of your initiative and our persistent moral support,” the letter stated, “the General staff has decided to go its own way….” Why? Because, the letter continued, of “a known strategical misconception in at least some of the higher military circles, deriving from the hundred year old feud between the advocates of mountain warfare and the supporters of military operations in level terrain. Belief here stands against belief, theory against theory. That difference of opinion on matters of this kind, however, may prove disastrous – if not adjusted in time – as has been shown in the most important winter and mountain battles of the past….”

Not a single member of Ninety-Pound Rucksack’s advisory board has ever heard of the American Mountain Warfare Research Institute, and the letter contained no signature. Still, the point remained: the mountain troops were up against more than just the mountains.

As the experimental ski patrols were winding down, momentum for a proper mountain unit was ramping up. The National Ski Association’s role as an advisor to the War Department had been formalized in a contract, and both it and the American Alpine Club had put together committees to advise the Army on clothing and equipment. Lieutenant Colonels Hurdis and Walker, meanwhile, had been directed to study high-altitude locations across the west suitable for both summer and winter manoevers that could accommodate 15,000 soldiers in a camp.

And yet, the resistance continued.

You’ll remember Colonel Henry Twaddle, the Army’s acting assistant chief of staff, who had reached out to The American Alpine Club in December 1940 to inquire about the type of clothing and equipment necessary to fight in the mountains. On April 2, as Hurdis and Walker searched for suitable encampments, Twaddle submitted a memorandum to the Army’s chief of staff, recommending the immediate construction of a camp in high mountain terrain in which a mountain division could train.

A high-stakes military pissing match ensued. For those who yearn to read the actual language grown men in uniform use to tell one another to go climb a mountain, rejoice: it will be included in the book, and it’s included in the chronology of events related to this episode, which is available, along with all our other bonus content, to our wonderful community of patrons. For everyone else, here’s a synopsis of what happened, stripped of bureaucratic double speak and translated, by yours truly, into civilianese.

April 14: Damnit, Twaddle, came the response from the Army. You know full well we don’t have time or money to build a specialized mountain unit, let alone a specialized camp for them to train in. Just take a division that’s already located near the mountains, ship them to your godforsaken hills and tweak them a detachment at a time until they can walk around in Alpine terrain without killing themselves. Or go to Bend, for all we care, and open a camp there. Now leave us around: in case you hadn’t noticed, Hitler just invaded Yugoslavia and Greece, and we’ve got an army to build.

Boulderdash, you idiot, replied General Twaddle (recently promoted): Germany invaded Greece to bail out the Italians because they couldn’t find their own asses in a blizzard without a map and an ice axe. We already looked at Bend: it has a short ski season, bad rock, horrific dust storms and not enough water for men or mules. We need a mountain division, we need a camp for a mountain division and we need it now.

Twaddle, came the reply on May 5, Germany’s bombing the hell out of London, the Royal Yugoslavian Army just surrendered to Hitler and you ain’t gettin’ a penny for a new site. If you don’t fall in line we’ll ship the mountain unit to a mountain meadow somewhere where you can pitch your tents.

Germany’s brazen betrayal of its ally Russia, which it invaded on June 22, did nothing to moderate the conversation.

“For the love of Peet,” General Twaddle tried again on July 15, “wake up and smell the edelweiss.” We need to make this work—and here’s another detailed memorandum, outlining how and why to do so.

Ten days later, Lt. Col. Mark W. Clark, who would go on to command the entirety of the Allied forces during the successful 1943-44 Italian campaign, chimed in with his support. “What he said!” Clark wrote to General Leslie McNair, the man who, as you’ll remember, had been directed by General Marshall to build out the army.

“Twaddle!” roared General McNair on August 5. “Bleep you and the mule you rode in on!

I don’t care if the Germans have mountain troops—if they had a division of courier pigeons, you’d want one of those too! You’re proposing 7,983 pack animals and only 369 motor vehicles for this unit. Every single howitzer will need 68 artillerymen and 68 animals. What is this, World War 1? Mash up an infantry battalion and an artillery battalion and figure out how to move them around in the mountains with jeeps. This isn’t the goddamned cavalry!”

History is what happens when we’re making other plans. On August 5, the very day that General McNair was telling Twaddle what he could do with his mules, a memorandum went out that changed the course of events. The Greek counteroffensive had driven the Italians back across the mountains of Albania in the dead of winter, and the American military attaché to Italy had submitted a report that laid the blame for their defeat on a lack of well-equipped mountain troops.

After the initial thrust had been turned back, the Italian high command had thrown untrained infantry divisions to the front of the line. “These divisions were not organized, clothed, equipped, conditioned or trained for either winter or mountain fighting,” the report noted. “The result was disaster. Twenty-five thousand were killed; ten thousand were frozen; large numbers made prisoners; loss in morale and prestige were irreparable.”

“One of the most important lessons learned from this,” the report continued, “is that an army which may have to fight anywhere in the world must have an important part of its major units especially organized, trained and equipped for fighting in the mountains and in winter… Such units cannot be improvised hurriedly from line divisions. They require long periods of hardening and experience, for which there is no substitute….”

Neither the lobbying efforts of the General Twaddles of the world nor America’s civilian climbers or skiers had been able to persuade the War Department to drop its opposition, but the report did the trick. The Italians, failing with catastrophic panache in the mountains of Albania, had convinced military planners to proceed with a mountain unit. On October 22, 1941, General Marshall and Secretary of War Stimson sent out the orders: the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry would be activated three weeks later on November 15th, at Ft. Lewis, Washington.

And then, twenty-two days after the regiment began to train, this happened.

[Radio broadcast] We interrupt this broadcast to bring you this important bulletin from the United Press. Flash, Washington: the White House announces Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

[President Franklin Delano Roosevelt addresses the nation] Yesterday, December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the empire of Japan. As commander in chief of the Army and Navy, I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense. No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory.

Following America’s declaration of war on Japan, its partners in the Axis, Germany and Italy, declared war on the US. Three days later, on December 11, 1941, Congress responded in kind. World War 2, the most destructive conflict in human history, was underway.

—–

And that concludes Episode 4 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening.

[Sound of car brakes screeching]

But wait. What happened to John McCown?

I’m so glad you asked.

I’m telling this story with John as the hero because the more I learned about him, the more fascinated I became with the way the mountains shaped him into the sort of leader others would follow. The 10th was not a faceless group of young men serving their country in an epic war. Rather, it was composed of thousands of climbers and skiers who, like John, came to the Division with their own motivations and backstories, trained together for three years, deployed to Italy, and executed their mission with stunning speed and effectiveness, in no small part because of their collective identity as mountaineers.

But that shared identity is made up of the tiny dots of their own personalities, and each was shaped by the mountains in their own way. They were all human, which means they were all inherently flawed; but they also possessed innate qualities of greatness, and the mountains made them shine.

I could just as easily have told this story through Albert Jackman, or Johnny Woodward, or David Brower, or any number of the characters we’ve already met in this podcast. But I’m telling it through John, because the mountains helped him inhabit the breathtaking richness of his own life, and this in turn inspired others to fight beside him for the America we love and take for granted today.

The morning after we left him, John woke to find his left ankle blown up like a balloon. And not just the ankle. “The whole foot was swollen,” he wrote. “Even the toes.”

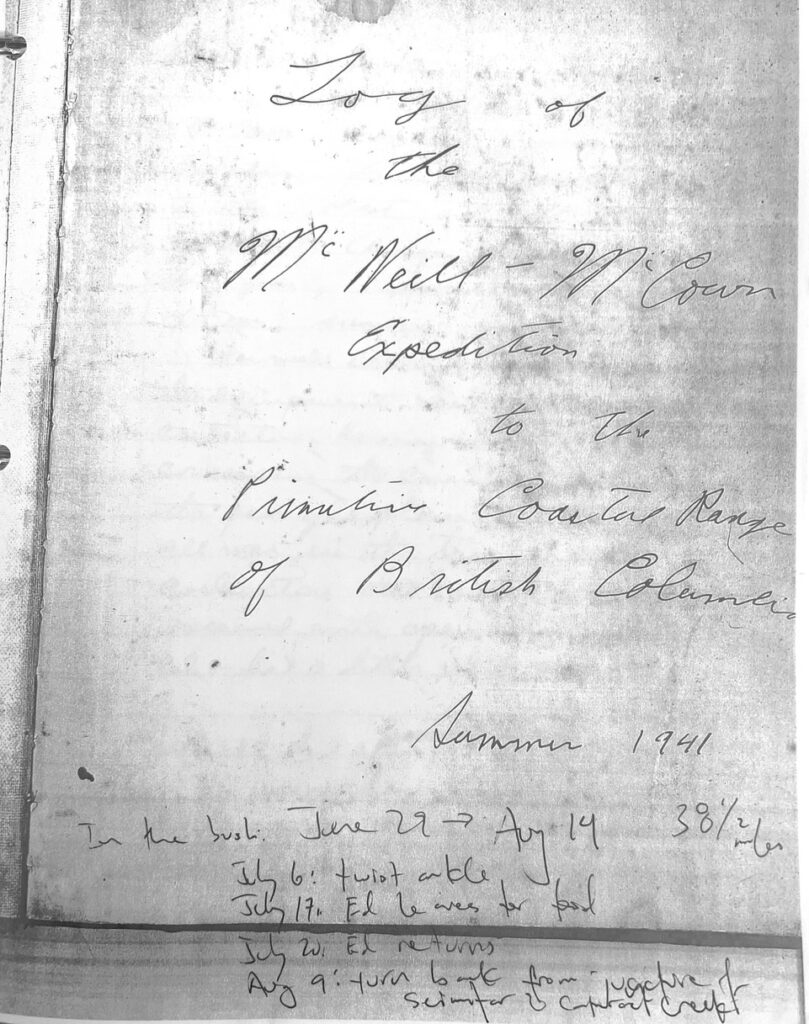

John and Ed recorded the details of their expedition in a journal, swapping scrawled entries as they made their way deeper into the range. After the accident, their focus narrowed to a single thing: food.

In addition to their clothes and kit and climbing gear, they’d brought rations: beans and rice and dried fruits and vegetables and soup and bouillon and chocolate and dried milk and sugar, salt, pepper and tea. But it wasn’t physically possible for two young men to carry enough food for a month-long expedition, so they’d brought their rifle and 50 shells and hunted for game along the way.

While John lay beneath the canopy of a giant fir tree—where he’d crawled, with Ed’s help, to shelter from the rain the night before—Ed went hunting. Unable to move, John contemplated his grotesquely swollen ankle and burned his name into their climbing hammer with an ice piton to pass the time. He also thought about their dwindling food supplies. “If we don’t get a sheep, deer, moose or bear,” he wrote in the journal, “our expedition is washed up.”

That was the optimist’s take. A pessimist would have noted that their car, along with additional provisions and the possibility of help, were a week and a half away, back up the Homathko River valley. A told-you-so’er might have pointed out there was a reason most people didn’t embark on climbing expeditions into the heart of the Coast Range as a two-man team: it left almost no margin for error.

Neither observation would have done John or Ed any good. Without food, they were screwed, and they knew it.

Day after day, while Ed traveled into the high country in search of game, John healed. After three days, he could wiggle his toes. After a week, he could bear weight. After ten days, with the help of a stick, he could hobble around. But still Ed failed to bag a single animal, and the state of John’s ankle was no longer their primary concern.

On their approach, they’d come upon a small, dilapidated trapper’s cabin set back from the Homathko in a grove of alders. Beaver, martin and deer skeletons lay scattered all around it, and a single glance inside was all they could stomach: desiccated entrails abuzz with flies gave the filthy room the putrid stink of death. But maybe, just maybe, there were provisions stashed inside.

While Ed left to find out, John remained behind, reading, writing in the journal—and despairing. “This weather seems to be adding insult to injury,” he wrote. “For this is perfect climbing weather. I am slowly going crazy here alone in camp with nothing to do, nothing to see, nothing to look forward to…. Just can’t say how low in spirits I am. This ain’t great.”

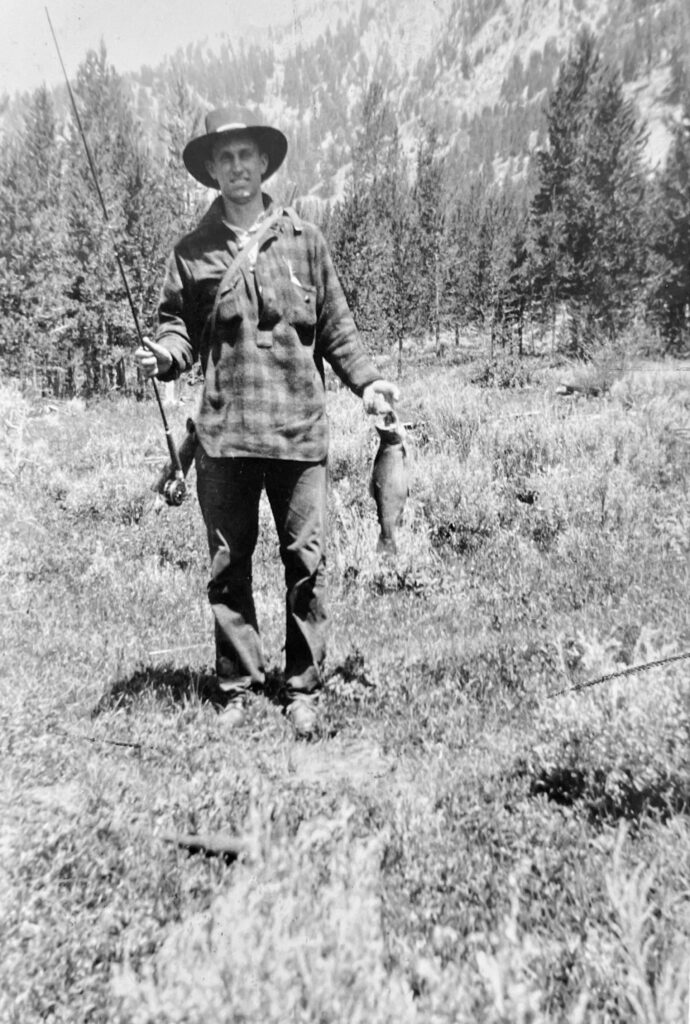

With nothing else to do, nothing to see, nothing to look forward to, John decided to go hunting. Taking his frame pack and his rifle, he began an arduous ascent up thousands of feet of steep, tedious terrain toward a ridge where he hoped to find game.

Hours after setting out, he reached the ridgetop, spied a goat, and killed it with a single shot, only to have it roll off the other side of the mountain. He hop-scrambled down to where it had stopped, removed the stomach and intestines, and lashed it to his pack. Dressed, it weighed 100 pounds. His trip back to camp took a full day.

Ed returned the following morning, and the two spent the next forty-eight hours gorging on the goat meat. And then—one month into their expedition, with another week to go before they were even in position to attempt a climb—they staggered stubbornly onward toward the glaciated flanks of Mt. Waddington.

Who does that?

John was set to start the University of Virginia law school in the fall. Heading home now would have gotten them back east with a few weeks of summer vacation still to enjoy. Most people would have thrown in the towel, called it good, and gone home. But not them.

History is comprised of facts, but people make it come alive. I’ve spent a year and a half trying to put together a physical and psychological portrait of John McCown so I could understand what made him tick.

Adversity, and our response to it, is a mirror, showing us who we really are. Three and a half years later, John would lead 200 men up the hardest line on Riva Ridge in the dead of night and the depths of winter toward the German soldiers waiting on top. Only one who knows himself—the brave bits and the fearful, the strong and the weak, the kind and the cruel, the considerate, the selfish, the patient, the rash, and all the thousand other dark and shining facets of ourselves that make up our limits and our potential—can inspire others to place their trust, and lives, in his hands. As John wrestled with his injury and its implications for his survival, bagged his goat, restored himself and Ed to full strength and then carried on, he was learning who he was—and in the process becoming the sort of man others would follow into battle.

I’ve tried to develop a physical and psychological portrait of John because he represented the kind of soldier America needed to win the war. Breaking the Gothic Line while incurring horrendous casualties along the way required the same sort of qualities John and Ed were developing now: resilience, self-reliance, tenacity and an unwavering confidence in one another and in one’s own abilities.

The information about John, though, is limited, and there are great gaps in his history that have defied my efforts to address them. World War II military personnel files archived at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri were destroyed by a fire that swept through the facilities in 1973. Some 17 million records, including John’s, were lost. The 10th Mountain Division Resource Center at the Denver Public Library, the official repository for the unit’s records and artifacts, has nothing beyond the information Susan provided to me. I’d gotten to a point where I thought I’d discovered just about everything I was going to find, and, for the purposes of our story, I’d resigned myself to developing John’s persona based on the materials I had in hand.

Fortunately for you and me both, I was wrong. Someone else has been interested in John as well. His name is Will Holland, and he’s a skier and writer from New England who has been working on a screenplay about John—for twenty-three years.

[Start, Will Holland interview]

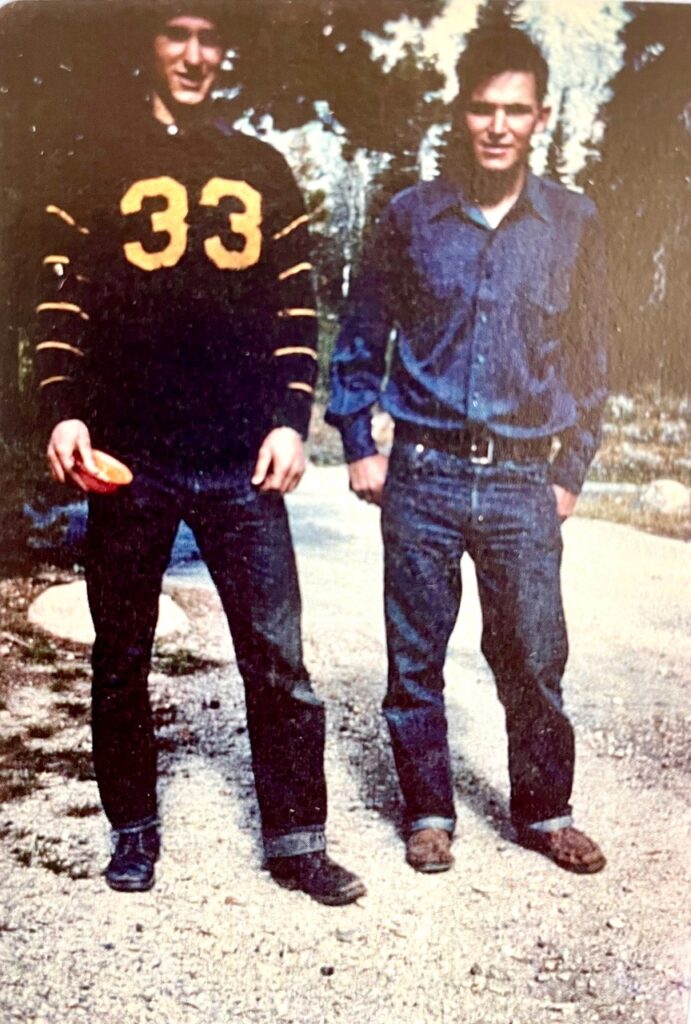

[WH] McCown struck me as a really larger than life character, kind of an epic personality. And when I started contacting relatives and found Susan McCown, his niece, and I went down to Villanova and she took me in the living room and spread out all the materials, all the photos and journals and all that sort of thing—it was just like I hit this gold mine and that’s when I really began to plunge into his inner space as reflected in his journals and both from the Tetons and from British Columbia. And that’s when I really got a sense of what he was all about. It was just a fascinating person, and so … admirable. I think I just was drawn to the strength of his persona and kind of like wanting to kind of absorb some of those ingredients into my own way of being, you know, because I found them so appealing. He had an insatiable appetite for every kind of outdoor experience that was available.

[Christian Beckwith] We’ve both been looking at similar materials that Susan has shared. I’ve been looking at it for a year. And you’ve been looking at those materials for 23 years, so you’ve done a lot more research on it than I have. What other insights do you have from those years? 1939, 1940, 1941—when he was still coming into his own and before he went into the army.

[WH] Oh my gosh. That trip they took to British Columbia with Ed McNeil was just amazing.

[CB] It was a moment in time as well. I was looking at that expedition and number one, Mount Waddington had only been climbed in 1936 by two of the best climbers in the country, if not the world. And for John and Ed, who had two seasons of Teton climbing under their belts, to assume that they could go in and make the second ascent of the mountain defines audacity. It was completely audacious. And part of that audacity was born in the fact that when you are that remote, because at that time was so incredibly wild—there was just nobody for weeks that could come and help them.

[WH] Yeah.

[CB] Anything that goes wrong is magnified by an order of 10. And so when he sprained his ankle like that, it became a matter of life and death. And I don’t think he’d ever really considered the implications of mortality before—based on, you know, everything that you shared with me. Mortality was not part of the picture, ever.

[WH] Yeah.

[CB] For Will, British Columbia offered insights into John’s very essence.

[WH] Just this kind of like can-do attitude, you know, that improvising left and right, living by their wits and skills. That’s the kind of life he found intensely fulfilling. Just driving yourself to the point of total exhaustion and then sleeping really soundly and waking up in the morning and having a huge breakfast. All these kind of like elements were to him the ideal way to live, you know, really in a very elemental way, in a very physical way, in a very embodied way. And I would say that about him too. He was a guy who, I think—he was magnetic and charismatic in part because he was so comfortable in his skin. He was so completely embodied. And somebody who was like that has a certain kind of gravitas. And I think McCown used that to very good advantage—plus being an extrovert and being outward oriented made him like, the ideal, because he inspired by his example. He didn’t have to be harsh. He inspired instant respect. I think it was his magic — his mojo.

[CB] Over the years of his research, Will connected with a number of people from John’s past, including Norm Wight.

[CB] Was Norm Wight his childhood best friend?

[WH] Absolutely. They had so many adventures together. One of the most paradigmatic adventures that I come across in Norm’s letters, it’s this wacky idea they had, they read somewhere in a Boy’s Life magazine or something about making your own scuba gear out of a five-gallon oil can. So Norm and John jumped on that dream of gathering freshwater clams from the bottom of Long Lake [in Maine] with their own scuba gear. So sure enough they found a way to cut the bottom of the five-gallon oil can, rim it with wood because it was very sharp, cut out a panel and put a glass window in there so they presumably could see. They put an eye bolt in the top and figured out a way to lower somebody into the water from a canoe. They came up with moccasins, each one with a five and a half pound weight in the moccasin, this metal bar. So they would sink to the bottom and a hose going into the oil drum and a bicycle pump on board the canoe so they could pump oxygen and they just went for it.

[CB] How old do you think they were at that point?

[WH] I think they were like 15. Something like that. So going out into canoe and then lowering somebody over the side was kind of complicated, so they eventually went with just starting on the short and walking into the water until they were like 10 feet, the guy was like 10 feet down, and John was down there for five minutes and he started to pull on the rope and has to be taken back up. And he said, it’s hopeless trying to bend over to gather clams because the water just comes gushing into your headpiece and so forth. So they got about, oh, maybe 15 minutes of actual use out of this rig. But he said it was just the whole adventure of rigging it up, putting together, it is just something that’s almost unfathomable for almost any teenager I know of today to dare attempt. That’s the kind of thing that risk taking and adventure and innovation that John was drawn to.

[CB] The one thing that really jumped out at me when I was reading his letters home in 1939 was how magnetic a personality was and how much people liked him. They just simply liked him. And I think part of that was because he was a strapping young lad. Very muscular, very rugged. Rugged is the word that always comes up. He’s very good looking.

[WH] Always.

[CB] What have you found in your diligence about his effect on the people around him?

[WH] Yeah, it’s interesting because I think a lot of people who have all those physical attributes of McCown might come across as arrogant or intimidating, but I don’t think he had that effect on people. I think he inspired more was comraderie than negative self-comparison in the people that he mingled with. And his effect on women I think was very powerful as well. As a young teenager, he and Norm—any talk of women, any talk of sex, was off limits. And Norm made that very clear. We never talked about women, we never talked about anything personal that was out, O-U-T, capital OUT and they would say that, no, I’m sorry, that’s OUT. I think romantically, he was probably a late boomer.

[CB] Reading over the letters that Norm wrote to you, there were a number of things that jumped out. One was they were always on the go. They never stopped. They were never home. I think they both ate at the other’s home twice over the course of their childhood.

[WH] Yes.

[CB] And the rest of the time they were on the go. But then also practical jokes.

[WH] Yeah, his sense humor was shown most strikingly in his practical jokes, which corresponds to the man himself. He’s a physical man and his humor took the form of physicality. One of the rhymes that the time was, “A farting man’s the one to hire, because a farting man will never tire.” He farted more than three normal people put together and never worried about how the aversive reaction that people around him might have to his tendency—never gave it a thought.

[CB] Norm’s letters included anecdotes about the sort of practical jokes John loved. In one of them, he wrote,

“The McCowns had a next door neighbor by the name of Bob Chapman,” he wrote. “Bob was not well–coordinated and not an athlete at all. Awfully nice guy [though] and wanted in the worst way to be included in events. He went with us, once, to the Poconos to go trout fishing…. [He was fishing in a pool [that lay] below him by inching out [along] a narrow ridge to get above deep water. Either John or I could have [just] walked out, [but] Bob did it with his back to the ledge. Bob was deathly afraid of snakes. John had found a garter snake and … was working his way to be above Bob [with the snake on a stick]…. Near these pools one couldn’t hear anything—the water made so much noise. John let the snake drop and it caught on a branch just above Bob’s head. John hollered and Bob looked up. Whe he saw the snake I really thought he was going to jump. It would have been fatal. He turned white, slide back along the ledge and collapsed on the ground.”

“I do believe John went into [practical jokes],” Norm continued, “without any thought of injuring anyone but also without any thought as to an unforeseen outcome.”

[CB] I had a childhood best friends and I always knew that whenever we did anything at all, we would get in trouble. Whether it was stealing cars or setting barns on fire or BB gun fights, we were always gonna get in trouble. And it was always the best time of my life. And John strikes me as a similar… cut from a similar cloth.

[WH] Yeah. Norm said, I’ll never had a friend like that sense. He said, that’s probably why I got into being a Maine guide so I could have that sense of fellowship. Introducing kids to the outdoors and taking people out into the wilderness. He said nothing ever measured up to kind of bond that I hadn’t John.

[End Will Holland interview]

John and Ed never made it to Waddington, in no small part because their brush with starvation had left its mark. The deeper they traveled into the range, the more obsessed they became with food. They killed anything they could—crows, squirrels, porcupines—and they ate it all: intestines, the eyes, the brains. Whenever they got something to eat they dropped everything else and ate it. Increasingly, all they could think about was eating. They even came up with a name for it. They called it the bloat: eating until they could eat no more.

Five weeks after leaving their car, they reached the glaciers that led to Waddington. They readied the clothing and equipment they’d so laboriously shlepped deep into the range and prepared to depart in the morning for their climb when John stumbled upon a colony of marmots. He killed one, then another; by the time he was done, he’d killed five. Rather than starting out on their ascent, for the next few days he and Ed committed themselves entirely to the bloat.

“Again but alas!” read their August 9 journal entry. “The climbing end of our expedition has hit another snag. No, we were not stopped by the weather nor physical fatigue, nor even better judgment. Rather, we were stopped by bloat trouble.”

Befittingly for a man of John’s physical nature, they were undone by their stomachs.

“It does seem a shame that we have thrown away our first real chance to scale a virgin peak in untouched wilderness just for the satisfaction of a complete bloat,” Ed wrote, “but this is a day I will remember just as much as I would a climb in the area. It seems strange the way one becomes almost primitive man on a wilderness trip of this type, making food the prime consideration before anything else.”

The next day, they began the arduous journey home “resolved never to eat a meager meal [again], but to bloat always.”

John made it home in time to start law school in the fall. His grades, though, were middling at best. He was no dummy: his senior thesis at Wharton, on the economic importance of Jackson Hole, is definitive, covering everything from ranching to hunting to park visitation and second home ownership in one of the most comprehensive examinations of the topic known to exist. But in the leadup to Pearl Habor, John’s mind was not on his studies. It was on war.

Some two weeks after America’s entry into the global conflict, John went to have his blood pressure taken. He was anxious, his doctor wrote, “to get in the ski corps.” Shortly thereafter, he dropped out of law school, enlisted in the Army and was sent to Camp Roberts in California for basic training. Soon after that, he joined the newly formed Mountain Infantry at Ft. Lewis—part of a wave of young American climbers and skiers who’d dropped everything to join the mountain troops and take on Hitler and the Nazis.

—–

And that concludes Episode 4 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening, and I hope you’ll tune in next time as we rejoin John McCown in British Columbia and pick up our story of the 10th in Ft. Lewis, as America’s first mountain unit begins to train.

We have one clarification to make. In Episode 2, Part 2, we noted that Chris Jones, Yvon Chouinard and Doug Thompkins made the third ascent of Patagonia’s Fitz Roy in 1968, but we failed to include the names of their teammates on the climb, Dick Dorworth and Lito Tejada Flores. Our apologies to both for the omission. If you catch a mistake, reach out and let us know so that we can maintain the show’s historical accuracy.

Special thanks today go out to our new patrons, Mark Newcomb, Austin Peterson, Gerry Aaron, Peter Carman, Russ Brinton, Stephen Spel, Neil Gleichman, Tucker Hermans, Daniel Fields, Mark Mooradian, Armando Menocal, Dan Burgette and Karen Kristie. Our community of patrons are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack because they make it possible to keep the show going. I hope you’ll consider becoming one too.

Thanks to our partners, The 10th Mountain Division Descendants, the Denver Public Library, The American Alpine Club and the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, as well to our advisory board members, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt, for their help in putting this episode together.

And very special thanks go out to Lieutenant General Christopher Donahue, Commanding General of the XVIII Airborne Corps, and Major General Greg Anderson, Commanding General of the 10th Mountain Division, for inviting me to the Division’s base in Ft. Drum, New York, to keynote the XVIII Airborne Corps’ leadership forum. The XVIII Airborne Corps is America’s contingency corps, ready to deploy anywhere in the world on an as-needed basis by air, land or sea. After twenty years of deployments to the Middle East, the 10th, along with the XVIII Airborne’s eleven other units, are embarking on a mission to rediscover their historic identity. I invite American climbers and skiers to join me in assisting them in their efforts, just as John McCown and his peers did during the division’s earliest chapter.

Until next time, thanks for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.

Christian,

I can’t tell you how much I love this podcast. As an outdoorsman, amateur climber, and big history buff, your podcast delivers everything I love to listen to. And as a military physician tasked with training troops to tackle medical problems in unique environmental circumstances, the whole podcast is both engaging and illuminating.

Embroiled in a bureaucratic battle of my own to train medics for winter and mountainous conditions, your most recent episode could not have resonated more. Time is a flat circle, and what is old is new. Even in special operations, the most flexible of the forces do I face resistance to adapting our medical training.

Thank you for pulling this altogether. I can’t wait for the next episode and book!

Thanks, Doc! I couldn’t agree more with what’s old is new: the 10th is currently embarking on a mission to reconnect with its historical identity. Time is a flat circle indeed!