Episode 5: Paradise

Available only to Patrons, this Unabridged version of Episode 5 explores the pivotal period from late 1941 until early 1942 when the War Department activated the 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment, America’s very first test force for cold-weather and mountain warfare, and it prepared to train in Paradise Valley on the flanks of Mount Rainier.

Available only to you, our community of patrons, this Unabridged version of Episode 5 features the complete interviews with Jenkins and Blyth, as well as historic photos, a transcript of the episode and a complete chronology of events leading up to the ski training that began in Paradise Valley in Mount Rainier National Park in February 1942.

Unabridged versions of both interviews are embedded in the transcript below.

Patrons are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Their support allows us to pursue the show’s journalistic and educational objectives as we detail the Division’s living legacy. In return, patrons receive exclusive access to Unabridged content for all episodes.

If you haven’t already, please consider becoming a patron. Our goal with Ninety-Pound Rucksack is to inform and inspire the public about the Division’s living legacy. Patrons make that possible. In return, they receive access to all Unabridged content.

See here for an overview of the characters mentioned in this episode.

EPISODE 05: PARADISE

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and today we’re recounting the 10th Mountain Division’s halcyon days: the pivotal period from late 1941 until early 1942 when the War Department activated America’s very first test force for cold-weather and mountain warfare at Ft. Lewis, Washington.

With its inimitable knack for names, the War Department called the unit the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment. They’d soon drop the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), so we’ll refer to the regiment today as the 87th to facilitate the narrative for civilian listeners.

In our last episode, we detailed the previous winter’s exploratory ski patrols that the Army had used as the 87th’s lab rats, as well as the domestic and global events that led to the 87th’s activation. We also recounted the adventures of our hero, John Andrew McCown II, on an expedition to British Columbia’s Coast Range. This podcast is part of the real-time research for a book I’m writing about McCown, the 10th and its impact on outdoor recreation in America.

With no precedent in American military history, and little legacy of mountaineering, everything about the 10th Mountain Division had to be developed on the fly. The exploratory ski patrols had allowed the Army to work up specifications for skis and winter clothing, but by the time the 87th began to come together at Ft. Lewis, it had yet to figure out how to train its new soldiers.

The climbs and expeditions the Army used to develop gear and clothing for the mountain unit are so important they’ll be covered in their own episode. Today, our focus is on the initial stages of the 87th’s training.

Ninety-Pound Rucksack is made possible by our community of patrons. If you’d like to hear exclusive interviews with some of America’s top alpinists, please go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. For $5 a month you’ll get historic photos and full transcripts from each and every episode as well as behind-the-scenes content available only to patrons.

So go to christianbeckwith.com and become a patron—and while you’re there, sign up for the newsletter so you never miss an update, and give the show five stars on your podcast app, tell your friends about it and help us to keep it all going.

We’re honored to be working on this podcast with our partners: The Tenth Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the American Alpine Club and The Tenth Mountain Division Descendants.

We’re also excited to announce a new sponsor: CiloGear, the Portland, Oregon-based company that makes the lightest, most durable, best-fitting alpine backpacks that money can buy. More Piolet D’Or awards for the finest alpine climb of the year have been won with CiloGear packs than with any other backpack, and their crazy attention to detail has earned them a rabid following among guides, climbers, skiers and alpinists alike.

But they’re not just for civilians: CiloGear’s new brand, CG Strategic, makes the world’s best mountain warfare packs and military equipment as well. From missions in the Far North to cutting edge pre-hospital systems, CiloGear and CG Strategic are your bombproof, form-fitting, featherlight pack solutions. They’re also 100% owned & operated in the USA. Check them out at cilogear.com.

And now, let’s catch up with our hero, John McCown, as he prepares to enlist with the 87th Mountain Regiment.

——

The McCown family sat around the dining table, their faces illuminated by the warm glow of candlelight. The aroma of ham and mashed potatoes filled the air, mingling with the faint scent of pine from the nearby Christmas tree.

Andrew McCown, Esquire, distinguished lawyer from Philadelphia, leaned back in his chair and surveyed his family with pride. His wife, Mary, sat beside him, anxiously twisting her hands as she listened to their sons dissect the headlines from the morning’s paper. Japan had begun its drive on Manila, the Nazi army was heading for Spain, and Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt had met in the Oval Office, mapping out their plan to, as the front-page article described it, “wage war on the seven seas and all continents and in the air above until Hitlerism is finally and completely exterminated from earth.”

Grove’s eyes darted behind his wire-rimmed glasses from his father to his older brother John. “I can’t believe you’re enlisting with the mountain troops!” he exclaimed, a mix of excitement and awe lighting up his oval face. “If you’re signing up, I am too!”

“Me too!” said their younger brother, Dick, a spirited sixteen-year-old who shared John’s dark hair, athleticism and impetuousness. He leaned forward over his plate. “The second I turn 18!”

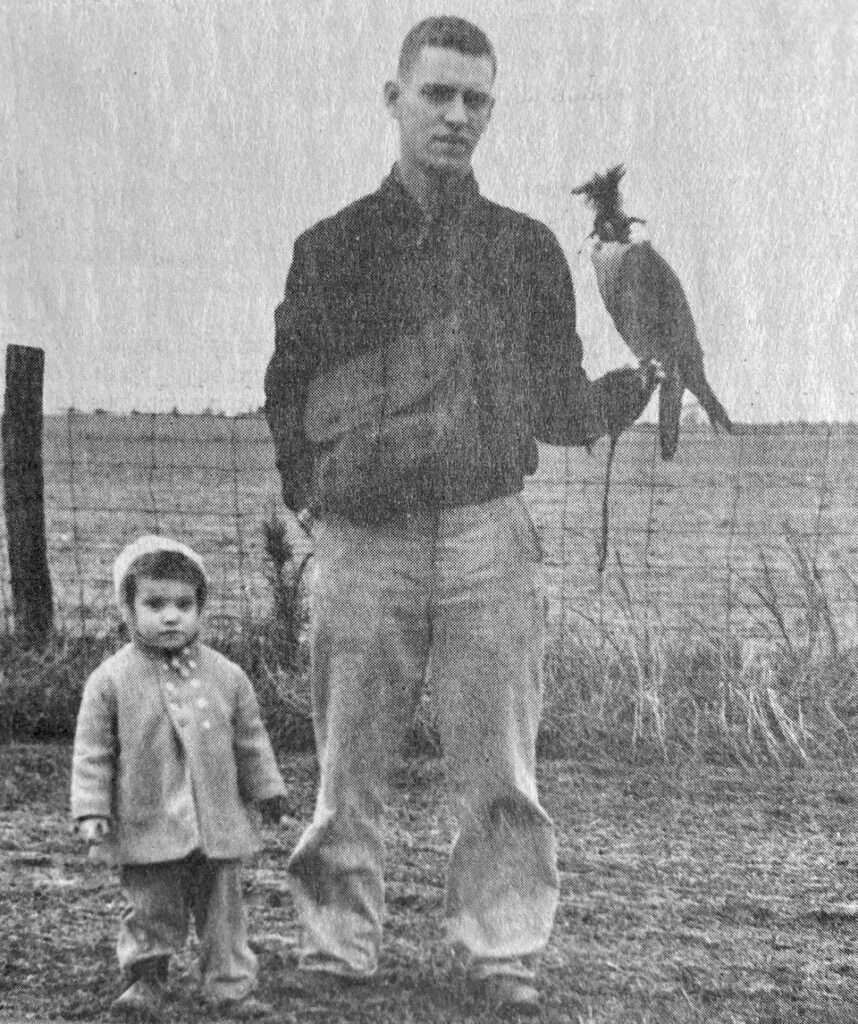

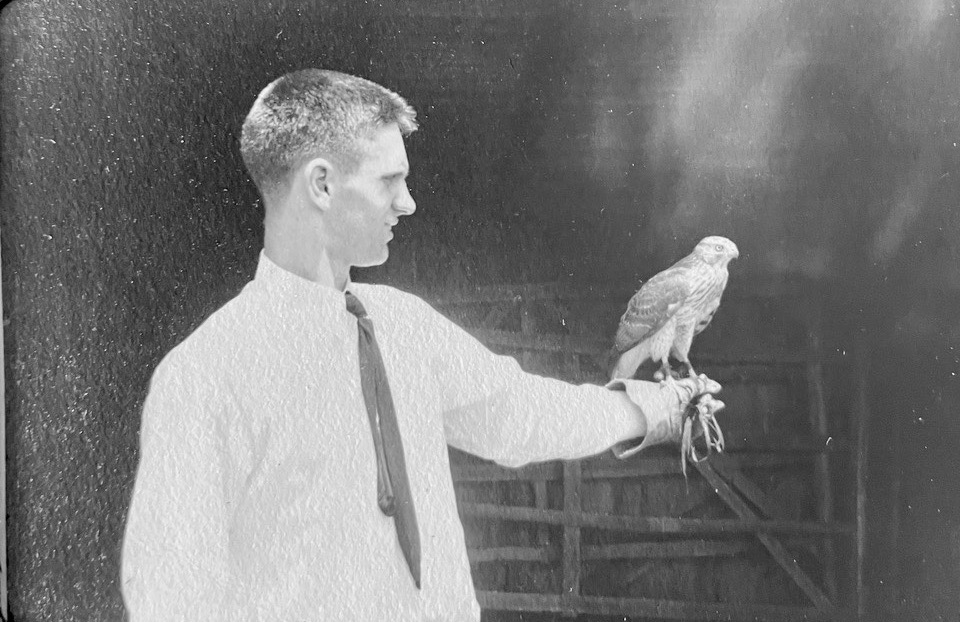

Their father raised his hand. “No one else is going anywhere until they finish school,” he announced. His gaze shifted to an empty place setting beside him, a solemn reminder of Andrew Jr., the youngest member of the family whom they’d lost three years earlier to leukemia. “And Dick, neither your mother nor I are taking care of your falcon, so you better start thinking about that too if you want to join the Army.”

John observed the family’s exchanges in silence. A faint smile graced his lips, but his mind was elsewhere.

It had been a month since the American Alpine Club envelope had arrived in his mailbox at the University of Virginia. He’d torn it open and read the letter inside again and again, as a wave of excitement built within him.

The letter, which announced the formation of the 87th at Fort Lewis, sought qualified AAC members to join its ranks. Henry Hall, the AAC’s secretary, had scribbled a note in the margins. “This aligns perfectly with your skills, John,” he’d written. “I’d be happy to write you a recommendation.”

John had met Hall at the AAC’s annual meeting the previous December as he was being inducted into the Club. Afterward, he’d shared a spot at Hall’s dinner table, and spent the evening engrossed in the dignified explorer’s stories of his expeditions to British Columbia’s Coast Range. Hall had been charmed by the attentive young man’s fascination, and he’d encouraged John to consider a Coast Range trip of his own. Their correspondence through the winter had laid the foundation for John’s expedition with Ed McNeill, and John had written to Hall the moment they’d returned with news from the trip. He hadn’t expected Hall’s response to include notice of the new mountain unit, but it had left him elated.

John had promptly accepted Hall’s offer, then filled out the attached questionnaire with details about his climbing experience. He’d secured additional letters of recommendation from a ski instructor friend from New Hampshire and his doctor at Wharton. The prospect of serving in a mountain unit was exhilarating, and he’d mailed the questionnaire and letters to the National Ski Patrol System at the organization’s recruitment address in New York City.

And then, Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor. Within a few days, John, like countless young men across the country, had abandoned his studies and enlisted.

John’s family glanced his way as they ate.

As the meal neared its end, Andrew stood up and walked over to the Christmas tree. Retrieving a small wooden box, he returned to the table and placed it before John.

“I know it’s Christmas eve,” Andrew said, “but I wanted you to have this.” His voice trembled slightly as he spoke. “Dropping out of law school couldn’t have been easy, but I’m proud of your decision, son, and I want you to know that I support you.”

John opened the box and peered inside. There, nestled in a bed of velvet, lay his father’s World War I issue Smith & Wesson .45. The gun glistened in the candlelight, its polished metal reflecting the flickering flames.

Andrew’s voice softened further. “I carried this with me during the war. Thankfully, I never had to use it. I hope you won’t either. Take care of it, son.”

John nodded, his eyes misting up as he reached for the gun. He ran his fingers over the smooth walnut grip, marveling at the weight of it in his hand.

But Andrew wasn’t finished. He returned to the tree, retrieved a second box and placed it beside the first.

“This,” he said, his tone serious, “is my combat knife. It’s not the prettiest, but it’s effective, especially in the trenches.”

John opened the second box, revealing a long, formidable blade with a knuckle-duster grip and a skull-cracking nut on the pommel. He lifted the knife out of its velvet bed, hefting it in his hand as he turned it over.

“Thank you, Dad,” he whispered, his eyes meeting his father’s. “I’ll make you proud.”

A smile tugged at the corners of Andrew’s mouth as the rest of the family looked on, their expressions a mixture of admiration and love.

“You already have, son,” Andrew responded, his voice cracking with emotion. “You already have.”

[line break]

At first, they came from the Army. In late fall 1941, roughly four dozen young men—all men—with backgrounds in skiing and mountaineering and mules and horses, veterans of cold-weather postings and of last winter’s experimental ski patrols, began to arrive at Fort Lewis, the sprawling military reservation just southwest of Tacoma. They were the nucleus of the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, and they were charged with unraveling the mysteries of the War Department’s directive: to (quote) “test and develop mountain and winter equipment, [and] formulate, develop and recommend changes in mountain and winter warfare doctrines” (end quote). Put more plainly, their job was to develop a mountain unit after its soldiers had already begun arriving—and write a manual on mountain equipment and tactics in the process.

Thirty-two year old Captain Albert Jackman, the lean, straight-shooting Princeton man we met in our last episode, brought the report he’d compiled on the 5th Division’s ski patrol, the insights he’d gained on a climbing expedition to the Yukon over the summer, and something else the Army sorely lacked: an official connection to the world of mountaineering.

Captain Paul Lafferty, thirty-one, had served as the Technical Advisor of the 3rd Division’s experimental ski patrol on the flanks of Mt. Rainier. He brought his saxophone, a swimmer’s physique, and his younger brother and climbing partner Ralph. Ralph had co-founded the University of Oregon’s ski team. More importantly, he had cowboy experience. Lafferty, who’d been ordered to assemble a cadre of skiers and mountaineers for the new regiment, put him in charge of the regiment’s mules.

Twenty-six-year-old Lieutenant John Woodward had served beside Lafferty as the 3rd Division’s ski instructor; he’d also helped lead the 41st Divisions’ ski patrols, making him the only man to take part in both. He brought degrees in economics and business from the University of Washington, a decade of intimacy with Rainier’s terrain, and the War Department’s official training film, “The Basic Principles of Skiing,” which he’d helped make that spring in Sun Valley.

In assembling troops for the 87th, the Army had put out a call to those already in its ranks. Soldiers with an interest in skiing, high altitudes and low temperatures could request a transfer to the unit, provided they’d already completed basic training and been in service for more than four months. Lieutenant John Jay, the great-great-great grandson of the first Chief Justice of the United States, transferred into the regiment from the Signal Corps, the branch responsible for military communications. He brought a diploma from Williams College, an unused Rhodes Scholarship that had been interrupted by the war, and the camera he’d used to make the War Department’s ski film.

Others, such as twenty-one year old Phil Lucas, arrived without a say in the matter. His father, Lee Lions Lucas, had homesteaded Jackson’s Hole in 1898, and his aunt, Geraldine, had, in 1924, become the second woman to climb the Grand Teton, the beneficiary of a teenage Paul Petzoldt’s guiding abilities; but despite having had to ski to school during Jackson’s six-month winters, Lucas wasn’t a skier. He was a rancher, and that’s what mattered to the Army. The new unit needed a way to move its heavy artillery, and for that they needed mules, and that meant muleskinners. Lucas had been drafted into the Army. He might not have skied, but he knew horses, so into the regiment he went.

In charge of them all was Colonel Onslow Sherburne Rolfe, a red-headed forty-four-year old who’d been selected to put the 87th together. Rolfe brought the nickname “Pinkie” from West Point, a Distinguished Service Cross and a Purple Heart from World War I, and prestigious postings in civilian and military schools alike. He didn’t ski, and his mountaineering experience might have been limited to a few hikes in Latin America at the tail end of the ‘30s, but he was brisk, direct and tough as nails. Hard-bitten and intensely curious, he also knew horses, and was the Army’s choice for a formidably hard job.

Washington had ordered the activation of a Mountain and Winter Warfare Board to oversee the 87th’s development. Colonel Rolfe was its President. Captain Jackman was its Test Officer, reprising the role he’d had with the 5th Division the winter before. Lieutenant Jay, who would go on to become the unit’s de facto historian, was Photographer and Meteorologist. An officer was charged with procuring the regiment’s clothing and equipment; another took notes. Lafferty, Woodward, a dozen commissioned officers and two dozen non-coms formed the nucleus of the entire experiment. As the drizzly maritime days grew short and the ground turned to mud on the training fields around Ft. Lewis, officers, muleskinners, and mountaineers alike convened around the unprecedented challenge of developing America’s first full regiment of mountain troops from scratch.

[line break]

The basic weapon of the US Army was the infantry soldier. Supported by all other branches of the Army and the Armed Forces, his job was to engage the enemy on the battlefield, defeat him, and occupy terrain. With his rifle and bayonet, the infantryman was the Army’s pawn on the chessboard of war.

Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall had tapped General Leslie McNair, Commander of the Army Ground Forces, to build out his army. It was a big ask: in order to defeat Hitler, the War Department had determined it needed to grow from 200,000 men and 12 divisions to 8.5 million men and 250 divisions in under three years.

As one military historian observed, the generals shared a vision for how to do so, and it revolved around the infantryman. They “imagined a comparative handful of men… picking themselves up from the dirt and mud after spending hours lying on the ground; … men who were wet, [and] shivering with cold; thirsty, hungry, tired and afraid, mentally scarred by the deaths of friends and by witnessing sights that would haunt them for the rest of their lives….” These men “would move forward under machine gun and artillery fire. Some would fall, but the survivors would close with the enemy and kill him in a foxhole or a bunker, a building or a ditch, or die in the attempt. All the machinery the Army possessed came down in the end to that one-act drama. And it was that moment, repeated a million times over, that Army Ground Forces was created to produce.”

In general, the smallest infantry unit the Army believed could operate and fight independently was the division, which had an authorized strength of around 16,000 officers and men. It was “triangular,” which meant its combat and support power was based on groups of threes. Thus, an infantry division was composed of three regiments, each of which consisted of three battalions. A battalion, meanwhile, was composed of three regular companies that were in turn supported by a weapons company.

General McNair remained opposed to a specialized division of mountain infantry, but he had approved the 1st Battalion of the 87th as a way to test the concept. It was designed to be both mobile and suppliable in rough terrain. Thus, it had fewer men and lighter weapons than a standard battalion, which in turn meant it required fewer rations and ammunition, all of which were to be carried by horses and mules.

The 1st Battalion now needed some 700 infantrymen to fill four companies—A, B, and C companies, each with an authorized strength of around 200 men, plus D, its 100-person heavy weapons company.

For the first time in its history, the Army had enlisted the aid of civilian organizations to help find those men. Operating out of its federally funded offices at 415 Lexington Avenue in New York City, the National Ski Patrol System, overseen by its co-founder and director, the tenacious, loquacious, bow-tie wearing Minnie Dole, was hard at work recruiting and vetting candidates for service. Dole and his right-hand man, John E.P. Morgan, a persuasive, corn-cob-pipe-smoking Harvard alum who had helped develop the Sun Valley ski area, had sent out a bulletin in the fall to the 1,000 or so patrolmen on the organization’s list, along with a questionnaire designed to capture information on applicants’ background and experience. The American Alpine Club and Sierra Club had done the same. Those interested in applying were directed to fill out the questionnaire and send it back to the NSPS along with three letters of recommendation attesting to their suitability for the unit. Such letters, Dole’s liaison in the War Department assured him, were an excellent idea, for they would impress upon the Department the seriousness of the Ski Patrol’s approach.

The strategy was warranted, for the Army had its doubts. More than a few high-ranking officers, not the least of whom was General McNair, felt that an unprecedented division of mountain troops, populated by civilian organizations—and climbing and skiing organizations at that—would produce an unorthodox, unmanageable, elitist bunch of mountaineers. Which, to a degree, it did.

Witness number one, and the first to enlist with the new regiment, was Charles Bancroft McLane, twenty-one, from Manchester, New Hampshire. A rugged 155-pounder with a Roman nose and a toothy smile, McLane was elite: he came from a line of Dartmouth graduates that extended back to his great grandfather. His father, a lawyer, was a trustee of the college, and his godfather was its president. He’d attended private school, studied in Switzerland, and competed in the 1938 Pan-American ski races in Chile as part of the US Ski Team. He was also unorthodox: the headlines he’d garnered for his impressive performances as captain of the Dartmouth Ski Team focused as much on his singular style, one that verged on breakneck catastrophe, as it did on his unparalleled string of victories.

But he was smart—wicked smaht, as New Englanders would say. And he was personable. He’d been elected captain of the freshman ski team soon after arriving at Dartmouth. He’d also been captain of the football team, rowed crew, served as the head editor of the school publication, participated in the literary society and been a member of the dramatic, missionary and French clubs. He was a natural leader, thorough and fair, and he’d stayed fit for skiing in the off-season by carving out the trails he’d ski in winter with pick and shovel. So yes, he was elite, and yes, he was unorthodox. Whether he was unmanageable remained to be seen.

McLane had been one of the first to stop by the Ski Patrol’s Manhattan office when it opened. Dole must have been downright giddy at the prospect standing before him, and he quickly advised the young man to “get in on the ground floor.” McLane took Dole’s words at face-value, got on a bus in the middle of November, traveled across the country and arrived in his green college sweater, a big white D emblazoned on the front, “one sleepy Sunday morning,” as he’d recall in the 1943 American Ski Annual, “with a suitcase, a pair of skis, and a War Department order to report for active duty with the Mountain Troops.”

The guards at the main gate thought he was kidding.

“A major at Corp Headquarters was more sympathetic,” McLane remembered. “He read my orders, telephoned half a dozen officers, read my orders again and smiled. ‘Lad, you are the Mountain Infantry,’” he said.

Dartmouth, you’ll remember from Episode 2, was more than a decade into its emergence as the epicenter of American skiing. In the 1920s, it had helped displace the Nordic mainstays of ski jumping and cross-country skiing with the faster, sexier styles of downhill and slalom. The introduction of Hannes Schneider’s Arlberg technique, which he’d perfected by teaching Austrian mountain troops to ski during World War I, had created a system of skiing, as well as a system of teaching skiing, that had swept the globe. Dartmouth had been central to the technique’s rise to prominence in America.

Over the course of a single decade, Schneider’s apostles, influenced in no small part by their desire to escape the rise of the Third Reich, had emigrated to America and fanned out into colleges and mountain towns from East to West, bringing his technique to the masses. With its low crouch and a lift and swing into the turn, it had opened the door to skiing’s defining allure: speed. Coupled with the ski trains of the early 1930s that had saved the railroad industry from bankruptcy, the simultaneous advent of rope tows, and the downhill and slalom races that had been invented to perfect the skillsets of the mountaineer, the technique catalyzed a revolution in winter recreation. By 1941, somewhere between one and three million Americans had taken up the nascent sport, with Dartmouth, the unrivaled alpine powerhouse of collegiate skiing, in the lead.

College ski teams were a logical place for the National Ski Patrol System to look for recruits, and Dartmouth was at the top of its list. Before the close of the war, 118 students and alumni from the college would enlist with the division. But just as the National Ski Patrol System was not the only civilian organization in the recruitment business, Dartmouth wasn’t the only one contributing volunteers.

At first in a trickle, and then, following Pearl Harbor, in a stream, new recruits arrived from the University of Vermont and UC Berkeley, from Stowe and Sun Valley, from flatlands and mountain towns alike. Many of the 87th’s soldiers, it should be noted, came from within the Army: they were enlisted men like Jay who transferred to the regiment voluntarily, or draftees, like Phillips, who ended up in the regiment whether they wanted to be there or not. But as word about the mountain troops got out, the ranks began to fill with a disproportionately high percentage of exceptional young men—men who were well educated, men of means, men who had taken refuge from Hitler’s megalomaniacal reign, and men at the vanguard of the thrilling, “elite” sports of skiing and climbing.

McKay Jenkins is an advisory board member for this podcast. He’s also the author of, among many other books, The Last Ridge: The Epic Story of America’s First Mountain Soldiers and the Assault on Hitler’s Europe. Here’s how he characterizes what happened next.

[McKay Jenkins] Now, almost immediately—and this becomes one of the most famous kind of moment in the history of the whole Division—word got out to these Europeans that this new mountain division was going to be formed in the United States and a wave of world-class skiers and mountaineers from Europe started to arrive, including a bunch from countries occupied by the Nazis—notably Austria and Norway. So you had some very famous people, in fact literally world-class or world-record-holding skiers coming here.

Also, it’s funny about this group: there were a lot of kind of blueblood aristocrats showing up. You had the sons and grandsons of extremely wealthy people, including one guy who was apparently the son of the Lea & Perrins Worcestershire fortune. He asked to bring his family along with him to the base, which of course is not typical. And then he went and rented a house in town right under the nose of the general himself.

[Christian Beckwith] He’s talking about Colonel Rolfe, who by summer would be promoted to the rank of Brigadier General.

[MJ] The general approached a realtor and said, “I’d like to rent that house.” And the realtor said, “I’m sorry, general, but Private First Class Duncan has already leased the house.”

As McKay details in his book, “Heirs to the Glidden paint fortune, the Funk and Wagnalls publishing empire and Baron George von Frenckenstein, nephew of the former Austrian ambassador to the Court of Saint James’,” were also among the new recruits.

The Army isn’t always the aristocracy’s first choice, and the arrival of bougie Americans was greeted by a degree of scepticism among the career officers charged with developing the 87th.

[MJ] The primary culture of skiing was Harvard and Yale and Dartmouth people and, you know, Williams and whatever from New England. And so they were not just Ivy League educated, they were also generally like blue-blood New England aristocrats. So you have these Midwestern and southern military officers being confronted with people that were there. If you want to think of it this way, they’re like class superiors. There was a certain amount of, I wouldn’t say bitterness, but there was like, we’re gonna find a way to keep you in your place.

This tension would continue throughout the Division’s development.

Regardless of the new recruits’ background, the first order of business was basic training: a regimented program of physical and mental preparation designed to strip away the individual and remake him into something the Army could use for its plans.

At the same time, the Mountain and Winter Warfare Board was trying to figure out what to do with the recruits once basic training was finished. It wasn’t easy.

Our advisory board member Lance Blyth is the Command Historian of North American Aerospace Defense Command and United States Northern Command as well as an Adjunct Professor of History at the United States Air Force Academy. He’s currently working on a history of US mountain warfare with the 10th Mountain Division as its focal point.

[Lance Blyth] Yeah, Rolf is basically given the mission, and pardon me while I look it up here. His basic mission is to, and I quote here, is to “develop the technique of winter and mountain warfare and to test the organization and equipment and transportation of units operating in mountainous terrain and all seasons and in coal climates and all types of terrain.” So he’s being given two [directives]: one, the operational side of mountain warfare. He’s also been given the testing side for the equipment and stuff that you need to do. So he’s been given two things that kind to go together, but he doesn’t really have any book. There’s no manual, there’s no doctrine to go to, and doctrine is basically a recipe book. It doesn’t cover everything. It doesn’t have to be followed. But if I needed to go do assault a town, I can pull the doctrine out on urban warfare and it says, here are the steps we think you need to do.

And you’re like, okay, those three apply, it gives you a starting point. He didn’t have much of that. He had a small amount of that. He had a section in the Operations Field manual, 100-5, well known to World War II historians on the US side, and he had a very thin cold-weather manual. Not much to it, to be perfectly honest now. And that was it. And along with that, he had a whole bunch of college boys showing up who needed to be trained. They were saying, “Hey, I want to enlist the Army.” The Army said, “here you go. Here’s your ticket report to Fort Lewis.” So he also had to do basic training. He had to organize everyone, have enough sergeants in this company and enough lieutenants in that company and enough … had to move people around in order to basically establish a battalion.

And that must have taken weeks of people going back and forth and — “No, no, no, you’re no longer in A company, you’re now in C company,” then you drag your stuff over, and “No, no, you got to go to B company” and you go back over, “oh hey, you know about mules—now you need to go down to the heavy weapons company.” It must have been a back and forth.

And of course, as all this is just starting to happen, Pearl Harbor’s attacked and so now it’s real. The United States is at war. So he really spends December and January forming, organizing, and training the battalion, the basic skills: marching, which the military really likes because it lets you move large units from place to place efficiently; rifle range—by World War II, the Army, from the World War I experience, had determined the best time spent training was spent using weapons. So they did a lot of shooting. They went on the bayonet range, on the bayonet course—but they do all that for about two months. It was supposed to be about 12 to 13 weeks, but he probably pushed it down to about eight to nine weeks is what it looked like because he did have a number of experienced cadres in in the battalion, so he was able, I suspect Rolf just truncated that training and got everything formed and ready to go.

The training began on Ft. Lewis the same way it was beginning for millions of others on bases around the country: Orientation, induction, uniforms, equipment, medical and dental exams, and an introduction to the military’s complicated rank structure, customs and courtesies.

Once the preliminaries were out of the way, physical conditioning—running, calisthenics, and obstacle courses—and combat training—marksmanship, how to throw a grenade, how to kill someone with a bayonet—came next. The recruits learned how to patrol, how to plan and avoid ambushes, how to assume offensive and defensive positions. They learned how to read maps, communicate in the field, and administer first aid.

The indolent options of civilian life were replaced by rigid discipline and a strict code of conduct. Basic training sucked, but that was part of the point: the new recruits were in the suck together. When they emerged on the other side, they were not only prepared for the rigors of military life. They were part of the same team, and ready to become pieces of the military’s chessboard.

Beneath the monotonous rains of early winter, the young men gradually became soldiers. By the end of January 1942, they were ready for what they’d signed up for. They were ready to learn to ski.

[Line break]

The previous winter, Captain Albert Jackman had headed up the Winter Warfare Board at Wisconsin’s Camp McCoy, compiling detailed notes on the clothing, equipment and training of the 5th Division’s experimental ski patrol. His reports had yielded key insights into what it would take to launch the test force at Ft. Lewis, but almost everything beyond that remained unknown.

Jackman had been assigned to the Mountain and Winter Warfare Board at Ft. Lewis to provide continuity to the Army’s efforts to develop its test force. The history of the Mountain Training Center, as the Army’s efforts to develop its mountain force was called, was written by Lieutenant John Jay, who would rise to become Major John Jay, Commanding Officer of the 10th Mountain Division’s Reconnaissance Troops, by war’s end. As Jay noted in his history, “The Board as set up was too small to operate efficiently. Colonel Rolfe was far too busy with his command duties to do much more than glance over the reports prepared for his signature by Captain Jackman. Lieutenant Jay was occupied with taking pictures of the experiments as well as making weather observations three times daily.” The officer assigned to procuring equipment for the troops ”spent a great deal of time shuttling about the country obtaining supplies. The result was that Captain Jackman and [the Board’s Clerk and Recorder] were working up to eighteen hours a day, seven days a week, trying to get their tests done and reports written on time.”

Complicating their mission was the fact that guidance on exactly how to build a mountain unit left much to the imagination.

“The directive was phrased in … general terms,” Jay observed, “undoubtedly because of the newness of the venture and the fact that at that time the War Department had no concept of where or when these new troops might be called upon to operate.” Colonel Rolfe repeatedly asked his commanding officers for advice, but they “merely told him to proceed as he saw fit, saying that they knew nothing about the development of the mountain troops and did not propose to try to interpret his mission.” Some of the higher-ups were even less helpful. They actually interfered with Rolfe’s task, threatening to absorb his personnel into a defense force for the entire West Coast.

One thing that was beyond dispute was that while Ft. Lewis made sense to the Army, it made no sense to the mountaineer. The 87,000-acre base had been cut from the glacier-scraped flats of the Nisqually Plain. It didn’t snow at Ft. Lewis; it rained, which turned the ground to muck. The incessant moisture cloaked the barracks in perpetual shrouds of fog. On the rare occasions when the rain stopped, the volcanic behemoth of Rainier appeared to the southeast, teasing the soldiers with its snow-clad majesty as they learned to bayonnet.

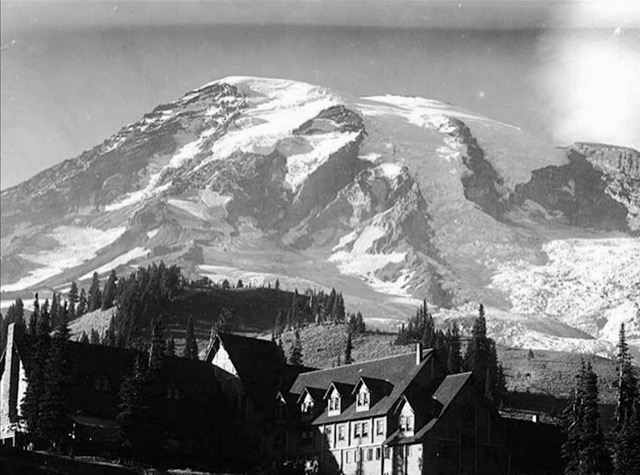

The experimental ski patrols of the previous winter had demonstrated that Rainier was an ideal place for an infantryman to learn to ski. It was also a two-hour bus ride from the base, and it lay within a national park, where it was illegal to use live ammo. This was a big deal, as weapons training with live ammo was critical to a soldier’s development. Still, if Colonel Rofle wanted to fulfill his mandate, the Park was his best option.

Inspired by a healthy dose of necessity, if not outright desperation, he engineered a feat of genius: he negotiated the lease, from the National Park Service, of the Paradise and Tatoosh Lodges on the southern flanks of Mount Rainier.

Nestled into the timberline at 5,400 feet at the volcano’s base, Paradise Valley is one of America’s most wildly beautiful places. Rushing mountain streams and cascading waterfalls etch deep river valleys and narrow canyons into high alpine meadows. Forests of spruce and fir and hemlock encircle the volcano, their floors covered in moss. From July until the end of September, a riot of wildflowers buzzes with bees and butterflies and hummingbirds. Black-tailed deer and elk graze among the lupines and avalanche lilies while mountain goats scale the steeper slopes and ravens and golden eagles soar overhead. To the southeast, the rugged summits of the Tatoosh Range, a compact line of jagged peaks, rise to elevations of over 7,000 feet. And looming over everything is the volcano, its vast, sparkling rivers of ice stretching down from the summit nearly two miles to the valley floor.

To accommodate the visitors who began flocking to Paradise Valley in the late 1800s, the National Park Service needed to construct a complex of buildings. Its goal in doing so was more than to simply provide them with shelter. It wanted to facilitate and enhance their connection to the land. For this, it utilized a building style known as alpine rustic architecture.

Inspired by the traditional architecture of the Swiss Alps, and popularized in the US in the early 20th century, this architectural style yielded buildings that were equal in majesty to the grandeur of their surroundings. Locally sourced stone and timber, steeply pitched roofs and large, exposed beams that emphasized structural strength and durability resulted in dramatic exteriors, while vast, unusual interior spaces reminded visitors of the sublime landscape outside.

The area’s first structure, the Paradise Inn, opened for business in the summer of 1917. Soaring gable roofs pierced by dormers arched into the sky, enclosing thirty-seven guest rooms and a vast lobby and dining area that could accommodate up to 400 patrons. A 104-room annex was added in 1920. Over the ensuing twenty years, more buildings—dormitories for employees, 275 housekeeping cabins, a cafeteria, a camp store, a ranger station, a guides’ hut and 40 additional guestrooms—continued to be built in the same architectural style. Like other Park Service triumphs such as Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Inn, the Paradise buildings blended seamlessly into their natural surroundings, providing visitors with a comfortable and harmonious architectural experience as awe-inspiring as the mountains all around them.

The masterstroke of architectural wonder may have been lost on the soldiers who arrived in February to begin their training. “Two stories were well under snow level, the third struggled, and still Park officials apologized for the measly 20 feet,” McLane remembered. [They] “said it was a light year.”

Leaving Paradise Inn for the civilians to use on weekends, the soldiers tunneled into their new digs. If they weren’t impressed by the accommodations, the surrounding landscape must have done the trick.

Paradise Valley wasn’t just a mecca for flower-sniffers. In the winter, its wild terrain had proven irresistible to America’s skiers as well. In late 1932, as skiing mania began to sweep the nation, the Park Service plowed the road to Paradise Valley for the first time. This was no mean feat; in 1971, the area, one of the snowiest places on earth, received nearly 100 feet of snow.

Overnight, Paradise Valley became a winter playground, and the Park concessionaire, the Rainier National Park Company, began leasing cabins for the entire season. There was only one problem: they were buried in snow. One person’s problem is another’s challenge, and rabid skiers soon had a solution: they simply dug shafts to the cabins, then connected them to one another and to the main lodge via a network of tunnels until they’d developed an underground city.

Skiing’s popularity was exploding and the National Park Service had no idea how to manage it. At first, it simply went along with the craze. In the Tetons, as you’ll remember from Episode 1, that meant building a rope tow on the morainal flanks of Bradley Lake, hiring Fred Brown as Grand Teton National Park’s ski operator and allowing him to organize annual 4th of July ski races in Cascade and Paintbrush Canyons. In Yosemite Valley, an Austrian skier opened the Yosemite Ski School at Badger Pass, which had a rope tow of its own. And in Mount Rainier National Park, local ski pioneers, with the Park’s blessing, decided to promote the fledgling sport with the most audacious ski race the country had ever known.

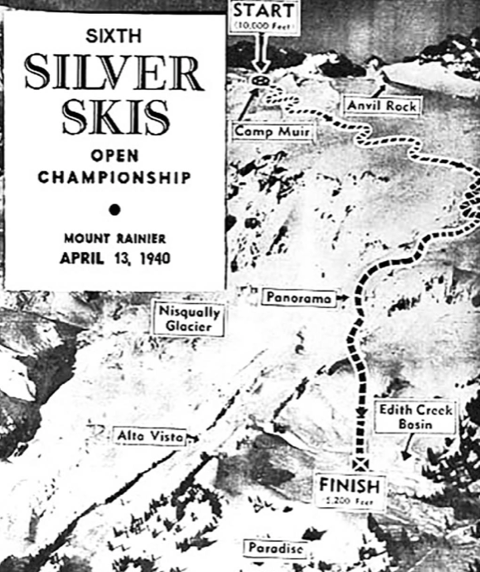

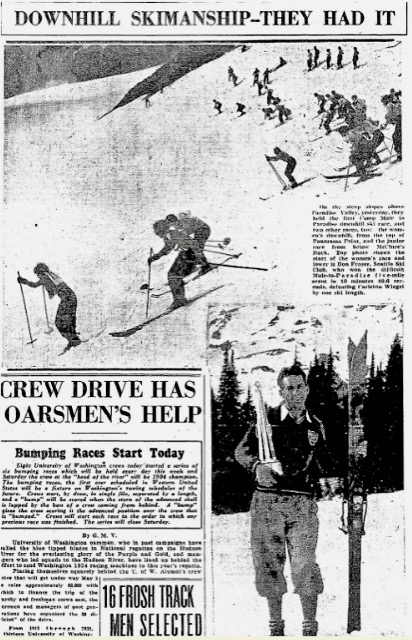

They called it the Silver Skis, and just getting to the starting gate was epic. It began with a four-hour climb from Paradise Valley to Camp Muir, a perch of horizontal terrain shoehorned into a ridge of volcanic rock at more than 10,000 feet. It ended four and a half miles and 4,600 vertical feet later in front of Paradise Inn.

The first Silver Skis was held on April 22, 1934. Sixty-six racers lined up at the edge of the declivity, the Tatoosh Range and the southern Cascades and the volcanic cone of Oregon’s Mount Adams just beyond the tips of their seven-foot skis. They pushed off into the yawning void in a mass start, soaring on hickory planks and light leather boots down a snow-covered tongue of ice amidst hanging glaciers and gargoyle cornices and sculpted seracs right to the throng of cheering onlookers gathered at the finish line.

It was mayhem. Twenty-two skiers failed to finish; four were hurt. “A downhill dash from Camp Muir — right up there in the clouds brother — to Paradise, a real test of the ski rider’s ability…” brayed the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, which, as the race’s sponsor, had a vested interest in whooping it up. The carnage and the race’s mammoth scale jolted skiers’ imaginations from coast to coast, and the blizzards and broken bones that followed only enhanced its notoriety.

By 1935, Paradise had transformed into the premiere ski resort in the Northwest, and the Silver Skis was its flagship event. In 1936, the resort held the U.S. National Ski Championships and Olympic team tryouts in its place, further burnishing the course’s reputation. As you’ll recall from our last episode, a young Johnny Woodward earned a spot on the US Team by placing fifth. The Silver Skis was back in 1937, along with the competitive realization that if you wanted to win, you couldn’t make turns. “America’s longest (and probably toughest) downhill ski race,” as the Times called it, had entered the realm of legend.

Paradise added a 500-foot rope tow in the winter of 1937-38, and the prominence of both Paradise and the Silver Skis continued to grow. In 1940, a competitor pushed off from Camp Muir, veered off course in a dense fog half a mile later, and hit a rock. He was killed—the first death in a sanctioned ski competition in US history. By April of 1941, when Woodward was finishing up his experimental ski patrols on the mountain, the Silver Skis had grown into the biggest, baddest race in the land, attracting skiers from around the world and audiences in the thousands. Thirty-nine racers competed that year; Woodward, skiing for the Army, finished fourth.

Imagine this: you’re a young man, bold and strong, and you’ve just joined the Army’s mountain troops. You’ve been plunked down in an architectural marvel, at the base of a 14,000-foot volcano, with twenty feet of snow outside your second-story window, a rope tow a short herringbone away, and some of America’s most intimidating ski slopes towering right above you. Now add some of the country’s top skiers as your instructors and you begin to get a sense of the scene that winter in Paradise Valley.

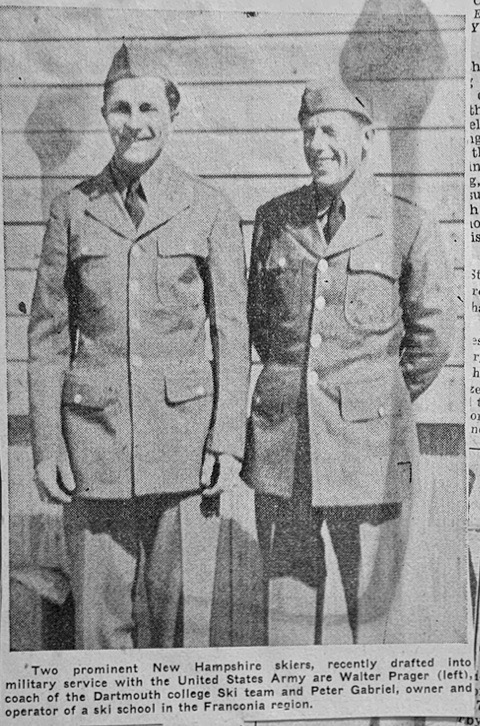

The only reason Woodward hadn’t skied in the 1936 Winter Olympics was because the University of Washington had decided it couldn’t afford to send him to Germany during the school year. The Norwegian-American Harald Sorensen, whom we met in our last episode when he was training a ski patrol in the Adirondacks, had qualified for the same games only to have his dreams thwarted by a lack of complete citizenship papers. He, too, was part of the instructor core at Paradise. So was Charles McLane. And so was McLane’s Dartmouth ski coach, a thirty-one year old Swiss mountain guide named Walter Prager who was one of the greatest skiers in history.

Prager had won the world’s first downhill championship in 1931, then won it again two years later. By the mid-thirties, he’d put together an unparalleled string of victories in cross-country, jumping and alpine races across the Continent. He’d also begun running a successful ski school at Davos, which is where he’d been discovered, from the American perspective, by Dartmouth college officials who were on the lookout for a new coach.

The school’s old coach was an Austrian acolyte of Hannes Schneider’s named Otto Schniebs. Schniebs had coached the Dartmouth ski team to the firmament of collegiate skiing, but the death of his daughter had prompted his resignation. Prager was hired to take his place. Dartmouth was over the moon. “Lean, tanned, and guaranteed to make the feminine element more than ever enthusiastic about the snow sport,” the school’s alumni magazine gushed in 1936, “Prager [has] arrived in town.”

It is unknown whether the slender Prager—who had also been the lover of Leni Riefenstahl, the actress who would go on to direct Hitler’s wildly successful Nazi propaganda films—lived up to his romantic billing, but he certainly held up his skiing end of the bargain. He solidified the college’s position in the skiing pantheon in part by modifying Schneider’s Arlberg technique, of which he was not an advocate, in favor of a Swiss style that employed a more flexible approach to tease out the inherent skills of the skier. As blasphemous as this might have been to Arlberg purists, it was effective, and over the course of five seasons Prager put together ski teams that exceeded his predecessor’s accomplishments. Three of his skiers earned US team spots for the 1940 Olympics—only to see them canceled by the outbreak of World War II.

Prager had served with the Swiss Army before coming to America, and in the spring of 1941, as the drumbeats of war grew louder in his adopted country, he’d taken leave from Dartmouth to join the war effort. Though he’d yet to become a citizen, he was already famous by the time he joined the 87th, and now here he was in Paradise, ready to serve beside—and at times beneath—his former students as an instructor.

The Army, in its infinite wisdom, had recognized that it needed civilian help if it wanted to get its test force right. It also recognized that it needed men who could do more than just ride a lift and ski back downhill, and it had asked the American Alpine Club to canvas its members for prospects. America had fewer than five hundred technically proficient climbers at the time. John McCown was one of them—hence his letter from Henry Hall. Others were brought to the Army’s attention via personal outreach at the highest levels.

Hall had written to the Army about just such a prospect the previous spring. “In connection with correspondence between you and [officers of] this Club relative to assistance which the Club might be able to give in the technique and equipment for mountain warfare,” he wrote, “I would like to call to your attention a man of exceptional experience and qualifications…. He is Peter Gabriel of Franconia, New Hampshire …, a professional ski instructor and licensed mountain guide who came to this country from his native Switzerland in 1937….”

Born into a guiding family in the spectacular mountain town of Sils Maria, Gabriel had made his presence known in North American mountaineering circles soon after arriving in the US. In 1938, he had joined one of the country’s climbing prodigies, the Harvard educated Bradford Washburn, on an expedition that mapped and photographed Alaska’s Chugach Range—and climbed the range’s highest peak in the process.

Gabriel and Prager, who were friends from New Hampshire, were part of the first wave of European emigres to join the new unit at Ft. Lewis. They also marked the beginning of an influx of some of the most extraordinary young men ever to wear an American uniform.

John Jay was one of them. He had learned to ski in 1934 at Woodstock, Vermont, on the country’s first rope tow, and he’d been filming the sport ever since. He’d captured skiers barrelling down the Headwall of Tuckerman Ravine during the infamous Inferno Race and documented the Winter Sports Show at Madison Square Garden. Time, Inc., the Canadian Pacific Railway, and Panagra Airline had hired him to write and produce promotional films when he was still in his early twenties. By the time he released Ski the Americas, North and South, the first feature-length ski film ever made, his career as the father of ski cinematography was underway.

With Jay documenting the proceedings, Captain Lafferty and Lieutenant Woodward organized a nucleus of about thirty men as the instructional cadre. “Their techniques were as varied as their names,” Jay wrote of the instructors. Now all they had to do was teach a battalion of soldiers to ski the military way—and develop a standard of military skiing in the process.

They had three things they could use as references. The first—or actually the last, if you’re looking at it chronologically—was a book-in-progress that was being put together by Bestor Robinson and edited by David Brower, two Sierra Club mountaineers we’ve met in past episodes and whom we’ll come to know well in the future, as both would play pivotal roles in the 10th’s development. The book, which would come to be known as the Manual of Ski Mountaineering, would become one of two pivotal compendiums of mountain knowledge to emerge in the spring of 1942, and we’ll go into more depth on both in our next episode.

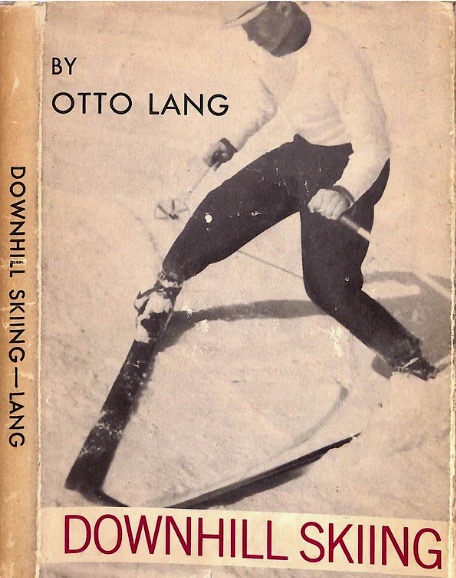

The other two references Lafferty and Woodward had at their disposal were a book entitled Downhill Skiing and a film called The Basic Principles of Skiing. Both were by the same man: Otto Lang.

The Arlberg Technique’s ground zero before the war was the Austrian resort of St. Anton am Arlberg, where Hannes Schneider taught it at his ski school. Schneider had hired Lang as an instructor in 1929. When the opportunity arose to escape Hitler in 1935, Lang had emigrated to America. He landed in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and promptly hung out his ski shingle. Poor Otto. New England winters serve up a mixture of weather, much of it—I grew up skiing on the coast of Maine, so I can actually say this—bad. On rainy days, Lang wrote down what he knew in a book. The result, Downhill Skiing, laid out for the first time the mysteries of the Arlberg technique for a fanatical American audience.

A combination of shitty weather, shitty terrain and shitty skiing (sorry, New England) prompted Lang to flee west, where he opened the first official American Hannes Schneider Ski School in—you guessed it—Paradise Valley. Soon, he’d opened similar schools on Mount Baker and Mount Hood, and he’d complemented his book with a film, Snow Flight, that showcased Schneider’s principles in action. Distributed by Warner Bros, the film premiered beside Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves at Radio City Music Hall.

In April 1941, Woodward had accompanied eight other members from the 3rd Division’s exploratory ski patrol to Sun Valley on the Army’s dime. Objective: make a film soldiers could use to learn how to ski. Its director was John Jay. Lang, who starred in the film beside Woodward and his fellow soldiers, was its spiritual and moral compass.

Sun Valley was the OG destination ski area, the first in the world to sport chairlifts, and the first to brazenly cater to the rich and famous. It had been built in under a year in the formerly-prosperous mining town of Ketchum by Union Pacific Chairman Averell Harriman as a way to save his railroad from bankruptcy. The Sun Valley Lodge opened in late 1936, just in time for the holiday season. It quickly attracted an A-list of Hollywood illuminati that would grow to include Marilyn Monroe, Gary Cooper, Clark Gable, Errol Flynn and Ernest Hemmingway, who, in 1939, finished For Whom the Bell Tolls in Suite 206. It also featured some of the best ski instructors in America, almost all of whom were Austrians and Germans who’d learned the craft with Hannes Schneider.

Nelson Rockefeller, scion of one of America’s wealthiest families and a statesman in the making, had been drawn to the new area as well, and he brought Lang, his personal ski instructor, because—well, because he could. At Sun Valley, Lang met the Austrian ex-pat Friedl Pfiefer, director of the Sun Valley Ski School.

Pfiefer was as famous as Prager. He’d begun instructing under Schneider’s tutelage at age 14. At 18, he’d become a certified climbing guide, and he’d become a member of the Austrian national ski team at 22. He raced, and when he raced, he won it all, including the world championship .

In 1938, Hitler invaded and annexed Austria. Schneider, who refused to embrace Hitlerism, was stripped of his ski school and imprisoned. Pfeifer fled for America, where he landed in Sun Valley and became a US citizen, the director of the resort’s ski school and the two-time winner of the US National Slalom title.

After he joined Pfeifer at Sun Valley, Lang quickly became instructor to the stars, which greatly influenced the development of The Basic Principles of Skiing. The film is notable both for its utility as a training tool and for its Hollywood-level quality. Professional voiceovers and professional acting complement the professional cinematography, which in turn is enhanced by the Sun Valley landscape. The film is good—so good, in fact, the backcountry aspirant could use it to learn to ski today.

But despite the fact that the film was specifically tailored for the military skier, Lang’s participation ensured that it enshrined the Arlberg technique, including its exaggerated rotation of the torso—and that, as we discussed in our last episode, was a problem for military skiing.

The Arlberg’s turn featured a swoopy shoulder swing that amplified the centrifugal forces of the weight on one’s back. A soldier who skied the Arlberg way while wearing a forty-pound pack risked getting catapulted by his own momentum—and whacked on the back of his head by his rifle in the process.

Woodward, you’ll remember from last time, had begun to develop a solution the previous winter while teaching the 3rd Division to ski. He began quieting a soldier’s turn by minimizing the rotation of his upper body. The Swiss school of skiing featured a parallel turn that did the same thing. Fortunately for Woodward, two of its foremost practitioners were now serving as his instructors.

With Prager and Gabriel’s help, Woodward and the rest of the instructors agreed on modifications. The Arlberg crouch and its progressive method of instruction could stay. The exaggerated rotation of the torso was out—which is why we no longer use it today. And in any other matters of technical dispute that might arise, the instructors agreed, Lang’s book would be the final say.

Look, I know I’m throwing so many names at you the top of your head is about to explode. I’ve toyed with coming up with a tiered system to help you figure out which of the folks I mention you should remember. Tier 3 would mean they’re a one-off. No need to remember them: I’m including them to make a bigger point. Tier 2 would mean you might want to pay attention: their contributions are worthy enough that they’ll probably reappear elsewhere in this series—but if you forget about them, no worries, I’ll reintroduce them later. Tier 1 would be important. These are the men who helped shape the 10th Mountain Division, and in so doing influenced outdoor recreation in America after the war.

Here’s the problem: almost every single person I’ve mentioned thus far in the episode would be a Tier 1 kind of guy. Pfeifer, like many Austrian and German emigres, was rounded up by the FBI after Pearl Harbor and given a choice: denounce Hitler and join the Army or spend the war in jail. He chose the former, signed up for the mountain troops, and was now—ta-da!—part of the instructor cadre in Paradise Valley. Hannes Schneider, meanwhile, was sprung from imprisonment by an American captain of industry who brought him to North Conway, New Hampshire, where he re-opened his transformational ski school. His son, Herbert, enlisted with the mountain troops, and Schneider, the so-called father of modern skiing, would soon be teaching soldiers of the 10th how to ski as well.

So please bear with me as we continue with our sprawling saga, which lies at the very heart of American military and recreation history. By mid-February 1942, as the Nazi juggernaut continued to roll across Europe and the US was still staggering from the body blow of Pearl Harbor and John McCown suffered through basic training hell—not in Ft. Lewis, for reasons we’ll discuss next time, but in California’s Camp Carson, 1,000 miles to the south—the stage was set at Paradise for a winter that would change everything.

[line break]

In February 2023, at the 10th Mountain Division’s base in Ft. Drum, New York, I gave a presentation on the history of the unit to the leadership of the XVIII Airborne Corps.

During the presentation, I highlighted the story of Charles Bancroft McLane, the first enlisted man to join the mountain troops.

Afterward, the 10th Mountain Division’s Command Sergeant Major Nema Mobar reached out. He was interested in honoring McLane’s service, and I provided him with the relevant details.

I also proposed that the Division consider honoring John Andrew McCown II.

On June 21, 2023, the 10th Mountain Division will recognize Captain Charles McLanes’ contributions with a memorial at the Hays Hall Conference Center.

It will also commemorate 1st Lieutenant John Andrew McCown II by renaming its Light Fighter School in his honor.

It has been a privilege to illuminate the sacrifice and service of these and other men of the Division, and to contribute, in however small a way, to the country they fought to defend.

[line break]

And that concludes Episode 5 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening.

Thanks to our sponsor, Cilogear, and our partners, The 10th Mountain Division Descendants, the Denver Public Library, The American Alpine Club and the 10th Mountain Division Foundation. Thanks, too, to our advisory board members, Lance Blythe, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt, for their help in putting this episode together.

If you enjoyed today’s show, please give it five stars on your app, tell your friends about it, and please consider becoming a patron. Many thanks to our new patrons who helped to make this episode possible: Nancy Kramer, Chris Hall, Mountain Doc, Kendrick Efta, Stephanie Spackman, Dennis Phillips, Yves Desgouttes, Daniel Tille, Max Ludington, Maria Hayashida, Thomas Campbell, Tim Poulterer, Craig Copelin, Eric Blehm, Jim Begg, Kaly Pass, Karen Tomky, JB Goldman, Molly Absolon, Mike I., and David Poseda. If you’d like to become part of the Rucksack community, go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button.

In our next episode, we’ll pick our story back up in Paradise as the officers and men of the 87th learn to ski. In the meantime, I hope you find a way to do something that scares you. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.

One small comment Christian as it might help in the publication of a book. I lived in the Northwest for 17 years and spent a significant amount of time on Rainier. I never heard Paradise referred to as “Paradise Valley.” It sits on a ridge line but sometimes names can be odd. Perhaps you have encountered the phrase in your historical research. It would surprise me though as I never hear Paradise referred to in any other way.

Thanks for your efforts. I love 90#R. It was cool to see you get some plaudits in the latest JHNews&G

Hey Neil,

Great to hear from you, and yikes! That’s some good, if alarming, insight.

What would the correct reference be, in your opinion?

I did find reference to “Paradise Valley” as I was researching the area:

http://www.alpenglow.org/nwmj/09/091_ParadiseSki2.html

https://nplas.org/paradise.html

https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/mora/adhi/chap14.htm

Let me know any insights you might have, Neil—always keen to get the facts straight.