Jackson Hole News & Guide Article, May 31, 2023

New podcast shows links between 10th Mountain Division and ascent of sport climbing.

By Mark Huffman

In the murk before dawn on Feb. 20, 1945, John McCown and other men of the 86th Infantry Regiment climbed the steep rocky slopes leading to the summit of Riva Ridge in northern Italy, a linchpin of the Gothic Line, the German defensive position.

The men knew that at the top of the ridge they would find Germans who already had retaken the position once from troops of the 10th Mountain Division, and they knew they would have to kill them to capture the position one more time. The Germans were ready to kill anyone who tried.

At dawn Lt. McCown led his men along a spur, yelling as they sprinted toward an enemy machine gun. The Germans opened fire, and McCown and six of his men died. The position was taken.

“He got 200 men up there to take the Germans by surprise” before the fatal patrol, Jackson climber Christian Beckwith said. “That broke the Gothic Line. … that precipitated the Germans’ surrender in Italy — that was John McCown.”

Five years before, McCown had stood atop the Grand Teton. He and well-known climber Joseph Hawkes had taken six hours and 20 minutes via the Exum route from Jenny Lake to the summit. Their ascent was recorded on the summit register on Aug. 3, 1939.

When Beckwith saw that register entry, he said in a recent edition of his podcast “Ninety-Pound Rucksack, “a lightbulb flicked on.” He knew the name McCown from the story of the assault in Italy, the famous Riva Ridge fight. He connected that heroic incident to climbs in Jackson Hole that he’d learned about from registers, the sign-in paperwork that used to be the common way to record a climb.

As Beckwith checked other registers he found that in 1939 and ’40, John Mc-Cown and his brother Grove “were all over the place” in the Tetons, “climbing routes both classic and obscure and attempting new lines on some of the range’s biggest objectives.”

It was serendipity for Beckwith, who had been researching what he initially thought would be a history of Teton mountain climbing. But as he dug into that subject his interest began to narrow: He encountered over and over the names of early climbers who also had served in the 10th, the only mountain division in the United States Army, storied for its bloody fight in early 1945 to smash the furious German resistance that blocked Allied forces from the wide flatness of the Po Valley.

The story of the 10th had been told as military history and told also as the story of thousands of vets who came home after the war and played a pivotal role in creating the resorts at the center of the postwar boom in alpine skiing.

But, Beckwith knew, the narrower story of the influence the men of the 10th had on mountain climbing hadn’t been a focus.

“It’s part of our valley’s history I’ve never seen talked about,” Beckwith said recently. And McCown, though just visiting from his home in Philadelphia for two seasons, was “a Teton climber,” Beckwith said. “He learned to climb here, did some amazing climbs here.”

At the start of World War II the United States had begun to prepare to fight tank warfare on plains, to battle enemy air forces, to attack and defend on the ocean and land troops in huge amphibious assaults, to drop airborne units. But it had no mountain troops.

See 10TH MOUNTAIN on 13A

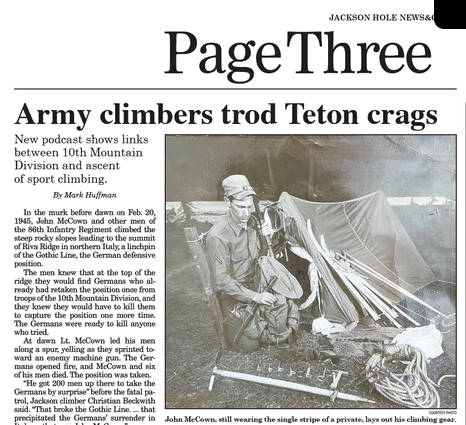

John McCown, still wearing the single stripe of a private, lays out his climbing gear.

COURTESY PHOTO

10TH MOUNTAIN

Continued from 3A

Mountain troops had for decades been a specialty of the Germans, Italians and Austro-Hungarians. The U.S. Army had to catch up, and the 10th Mountain was created in 1941 and soon began training at Camp Hale in Colorado, between Leadville and where some of the troops years later would create Vail. Starting the 10th was a chore beyond creating just another infantry unit: Beckwith researched the membership rolls of climbing clubs around the country in the years before the war and estimates there were only 500 or a thousand serious climbers in the whole country as the U.S. entry into the fighting approached.

When the 10th was created it spent most of its time getting ready. While the war raged the mountain troops practiced, and it wasn’t until January 1945 that the division arrived in the Appenine Mountains of Italy to face the German army.

The 13,000 men of the 10th, though they fought for only a short time, 114 days, had 969 killed and 4,154 wounded — but broke the Germans.

For Beckwith the story that hadn’t been told repeatedly was what thousands of young men trained to climb would do when they returned home when the guns fell silent.The “real grace” of the men of the 10th, Beckwith said in one edition of his podcast, “came later, as its soldiers returned to civilian life and fanned back out into the mountains they’d come to love.”

Though Lt. McCown didn’t have a chance to come home or again climb the peaks he loved, many others did. Among them were Paul Petzoldt, the founder of NOLS, the National Outdoor Leadership School, the country’s premier wilderness skills school, and David Brower, climber, author and president of the Sierra Club. Others were closer to the Tetons, the focus of Beckwith’s podcast and the book he is now writing.

Included in that group were Joe and Paul Stettner, German brothers whose family had fled the Nazis before the war and ended up in the 10th. On Sept. 1, 1941, they signed the register at the summit of the Grand, the last to reach that height before the United States entered the war and climbing came to a halt. The first climb in the last days of the war was by Joe Stettner, who ascended the Owen-Spalding route and signed his name on Aug. 26, 1945.

“For four years there was no climbing, no other entry until 1945,” Beckwith said. “And then it’s Stettner again.”

Another was John de la Montagne, who came back from the war to work with the Snow King ski school and in Grand Teton National Park. He was a leader in developing the techniques of mountain rescue and helped create the Jenny Lake Rangers.

Also part of the return were Ernie Fields and Doug McLaren, among the founders of Teton park’s rescue team, and Monty Atwater, involved in the early days of avalanche science, and Dick Emerson, one of the first National Park Service employees hired primarily for his climbing skill.

Others were Martin Murie, part of the Murie environmental family and a writer, and Ted Major and Phil Lucas, who found a job in the Army when it learned he could run a mule team, an essential skill in the 10th Mountain, and who came home feeling “he never wanted to see another mule in his life,” Beckwith said.

As Beckwith came across one story after another of 10th Mountain vets with a Teton link, “it just fascinated me and pulled me in.”

He eventually tracked more than 400 vets of the 10th Mountain, especially those with a Teton link, and especially those who had climbed the area and used their training and experience training in Colorado and fighting in Italy to make a postwar life that was grounded in scaling high peaks.

The result is a podcast — and eventually the book — that tells about “the ripple effect after the war” when a lot of young climbers came home and had a huge amount of war surplus gear to use as they looked to the mountains.

“It’s about how Teton climbers influenced the 10th and how 10th climbers influenced climbing in the Tetons,” Beckwith said.

Beckwith’s podcast, “Ninety-Pound Rucksack,” can be heard by going to his website, ChristianBeckwith. com, or through the usual podcast platforms, including Apple, Spotify and Google.

Contact Mark Huffman at 732-5907 or mark@jhnewsandguide.com.

Grove and John McCown on a Teton peak before the war.

COURTESY PHOTO

NOLS founder Paul Petzoldt climbs during training.

COURTESY PHOTO

Joe Stettner at Camp Hale, in Colorado, where he was among the most valuable trainers. He was too old to go into combat but worked as an instructor.

COURTESY PHOTO

Copyright (c)2023 Jackson Hole News&Guide, Edition 5/31/2023

o