Episode 8: Gear Heads, Part 1 is the first segment of our two-part mini-series that examines the equipment, clothing and food developed, at great expense, for the 10th Mountain Division. Not only did this development make the soldiers’ ability to train for cold-weather and mountain offensives like Riva Ridge possible; post-war, it catalyzed the explosive growth of America’s nascent outdoor recreation industry as well.

Episode 8: Gear Heads, Part 1

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and it is so great to have you back with us today as we continue our story of the 10th Mountain Division with one of its most important, and least appreciated, chapters.

Today’s episode is the first installment in a two-part mini series that examines the equipment, clothing and food developed, at great expense, for the mountain troops. Not only did said development make the unit’s training possible; post-war, it catalyzed the explosive growth of America’s nascent outdoor recreation industry.

As we’ve recounted in past episodes, skiing before the war had gone from the quixotic pursuit of a handful of daredevil ski jumpers to a full-blown national obsession. “The popularization of skiing has really come about during the past ten years,” Roger Langley, the National Ski Assocation’s President, reported in the 1939-1940 American Ski Annual, “Skiing is … said to be a $20,000,000 industry… [with] at least 1 million devotees in this country.”. [D]uring a normal winter, skiers might be expected to spend $3 million for skis, bindings, and accessories; $6 million for clothes; $500,000 for instruction; $3 million for transportation; $3 million for lodging; and $4,500,000 for such adjuncts as cigarettes, potables, ski tows, photo supplies and communication.”

Those might seem like big numbers, particularly when adjusted for inflation: 1940’s $20M is more than $420M today. But they pale in comparison to the sport’s current economic impact, which the Bureau of Economic Analysis pegged at $5.84 billion in its November 2023 report.

Climbing before the war was too small to even register on the economic Richter scale. Today, the BEA reports that the real outdoor recreation value of “climbing, hiking and tent camping”—the smallest breakouts it compiles of the category—is $4.9B.

To go from $500M to more than $10B in eighty years is a hell of a leap, and much of the credit for that stratospheric growth lies with the 10th Mountain Division, as we shall soon see. So settle in and get ready for today’s journey, because if you like to climb, ski or get outside in just about any form, chances are you owe a round of thanks to the 10th—and once we’re done with today’s story, you’ll have a better idea of whom to toast.

If you’re just tuning in, Ninety-Pound Rucksack is my real time research for part of a book I’m writing about the real-life adventures of John Andrew McCown II, a young man from Philadelphia who learned to climb in the Tetons during the Depression and went on to help engineer the 10th Mountain Division’s signature offensive during the war. Not only did the 10th’s 1945 ascent of Riva Ridge in Italy’s Apennine Mountains help break Hitler’s Gothic line, end Germany’s occupation of Italy and hasten the Allied victory in Europe; post-war, 10th Mountain Division veterans laid the groundwork for the outdoor recreation industry we love and all too often take for granted today.

In the eighty years since the 10th’s inception, the public’s recognition of and appreciation for the Division’s pivotal role in American society have regrettably diminished. To honor its legacy, we keep Ninety-Pound Rucksack free to all listeners, but the work that goes into each episode is expensive, and we couldn’t do it without our community of patrons. If you want to keep listening for free, great; we’re excited to share our story with you. If you want to help us keep the show going, though, and you can afford the cost of a cup of coffee, go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. For as little as $5 a month you’ll become more than just a listener; you’ll become a crucial part of our storytelling journey. You’ll also get exclusive content available only to patrons, including the more than half a dozen interviews and bonus episodes we’ve published in the past two months alone.

So go to christianbeckwith.com and become part of the community—and while you’re there, sign up for the newsletter so you never miss an update, give the show five stars on your podcast app, leave a review and tell your friends about it so we can keep telling our story.

Ninety Pound Rucksack is also made possible by our awesome advisory board of the Division’s foremost experts; our partners, the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, The American Alpine Club and the 10th Mountain Division Descendants; and our sponsors, CiloGear and the 10th Mountain Whiskey and Spirit Company. And if someone you love loves mountains, you’ve come to the right place, because both CiloGear and the 10th Mountain Whiskey and Spirit Company are offering discounts to Ninety-Pound Rucksack listeners.

Any great mountain adventure requires a great pack, and if you’re in the market for the lightest, most durable, best-fitting alpine backpack that money can buy, CiloGear has you covered. I’ve been using my CiloGear 3030 Worksack on climbs here in the Tetons and in the Dolomites, and it’s the best alpine pack I’ve ever owned. It’s comfortable, the materials are bombproof, it never gets in the way of my climbing, it does everything I need it to do when I need it—and the rest of the time, I never notice it’s there.

CiloGear is 100% owned & operated in the US , and if you go right now to their website at cilogear.com and enter the discount code “rucksack,” you’ll get 5% off and they’ll make a matching 5% donation to the American Alpine Club.

The American Alpine Club has been supporting climbers and preserving climbing history for more than 120 years. AAC members receive rescue insurance and medical expense coverage, providing peace of mind on committing objectives. They also get copies of the AAC’s world-renowned publications, The American Alpine Journal and Accidents in North American Climbing, and can explore climbing history by diving into the AAC’s Mountaineering Library. Learn more about the Cub and benefits of membership at americanalpineclub.org, and get a taste of the best of AAC content by listening to the bi-monthly American Alpine Club podcast on Spotify, Apple podcasts, or Soundcloud.

As we all know, the best way to finish a great day in the mountains is with a finely crafted spirit, and nobody captures the spirit of the mountains better than The 10th Mountain Whiskey & Spirit Company. I am continually impressed with their philanthropic commitment to The 10th as well as the smooth sophistication of their lineup. Their Awarding-Winning Bourbon and their Rye Whiskey are my go-tos for an after-climbing cocktail, and if you go to their website, www.10thWhiskey.com, right now and use the discount code Rucksack, you’ll get 10% off your order. Purchases over $150 get complimentary shipping.

Please drink responsibly. Must be 21 or older to purchase.Must be of legal drinking age to consume alcoholic beverages or to purchase them.

And with no further ado, let’s catch up with our hero, John McCown, as he prepares for the greatest adventure of his life—one that not only helped win the war, but that ignited a passion for the outdoors that reshaped American society in the process.

—-

1st Lieutenant John Andrew McCown II knelt before his equipment, his broad frame casting a shadow against the weathered floorboards of the old stone farmhouse as he sorted out his gear. He’d propped his Army-issue rucksack against the wall, laid his rifle to one side and put the rest of his equipment in a pile on the other. Piece by piece, he selected an item from the pile, held it in his outstretched hand as if weighing it, then either returned it or placed it in front of the rucksack in a neat, orderly row, the wooden floorboards creaking under his weight as he moved.

Fading daylight streamed through the dirty windows and a draft snuck into the room through a gap beneath the wooden door. He could feel the temperature dropping outside as he lined out his ammo and hand grenades. The frigid winter landscape that had greeted the troops when they arrived in Italy’s Apennines in January had given way to an unseasonable thaw, and the higher temperatures had melted much of the snowpack. Now the exposed dirt softened each morning, turned to mud, then froze into an icy, coagulated mire as the sun dipped behind the ridge at noon and the temperatures plummeted in the shade. Most of the snow on the east-facing ridge itself had melted off, too, swelling the Dardagna River at its base with runoff and adding another factor for John to consider for tomorrow’s climb.

He placed his father’s Smith and Wesson .45 carefully below the grenades. He’d polished the blued metal until the barrel and cylinders practically glowed in the dim light, but he couldn’t decide if he should bring it: it weighed 36 ounces empty, and every ounce counts when you’re climbing.

He didn’t know what to do with the combat knife, either. It was a nasty piece of work: double-edged steel blade with a blackened finish, cast-bronze knuckle-duster grip and a skull-cracking nut on the pommel. But it, too, was his father’s from the last war, and he set it with a gentleness that was almost reverent alongside his rifle.

The room’s stone walls bore the weight of time. Cobwebs adorned the exposed wooden beams of the low ceiling. Farm tools—a scythe, a spade, a hoe—stood in the corner next to the door, etched with the scars of long use. Shelves held a few earthenware pots and copper pans, and an oil lamp sat atop the rough-hewn wooden table in the center of the room—but there would be no fires tonight, no conversation between soldiers, no cigarettes shared during the changing of patrols. Silence enveloped the valley, commanded by the need for stealth, as any noise, any movement, any trace of light could betray the presence of John and his fellow soldiers to the Germans perched high above them on Riva Ridge.

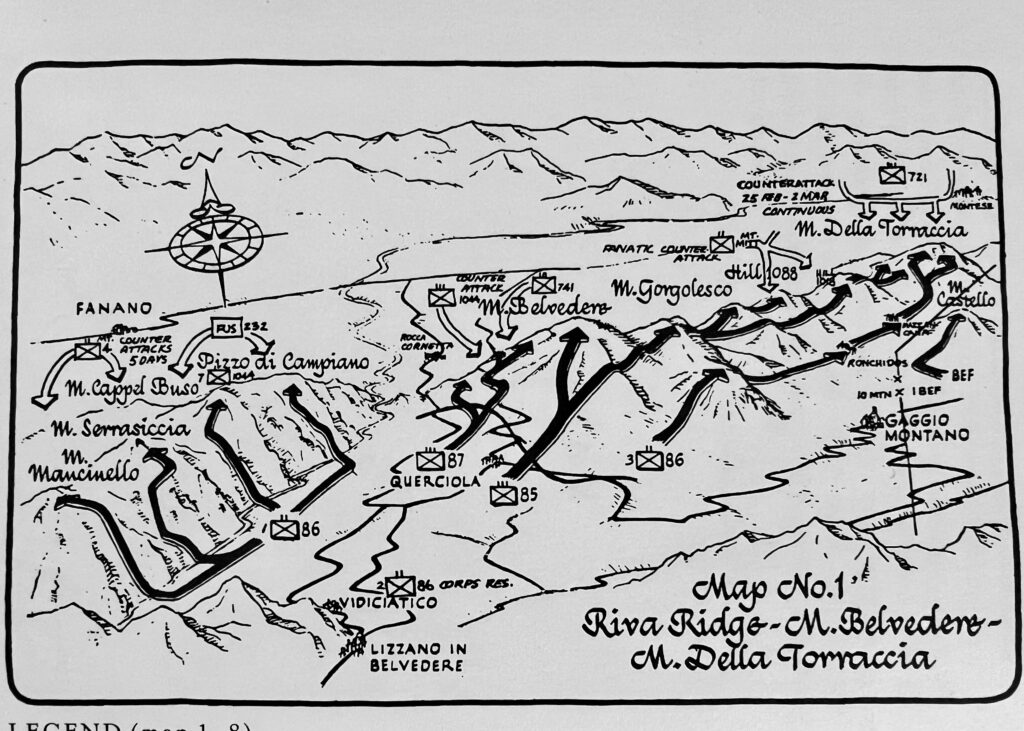

It was February 17, 1945, and similar scenes were playing out by the hundreds inside the clusters of stone buildings scattered throughout the valley. John and his C Company men were billeted in Miglianti, the closest set of buildings they could find to the start of their route. Forces A and B were down valley in Pianacci and Ca di Julio, near the bridge at the beginning of theirs.

Force D was up valley at Poggioforato, the only collection of farmhouses big enough to be called a village. Wherever they were located, the soldiers of the First Battalion, 86th Mountain Infantry were doing what John was doing: quietly cleaning their arms, sharpening their bayonets and sorting through the contents of their packs as they deliberated what to bring and what to leave behind with their bedrolls for later retrieval. If there was a later. Rumor had it that the brass expected 80% casualty rates.

John plucked his bayonet from the pile and placed it beside his rifle. He’d sharpened it until it could cut paper, and the blade glinted dully in the growing gloom. Better than anyone else in C Company, he knew what tomorrow would bring. He’d reconnoitered the route himself, leading his four-man patrol up the steep slopes under cover of darkness as he pieced together a way to the top, tap-tap-tapping pitons into the steps of shattered sandstone with a hammer he’d wrapped in cloth to muffle the blows.

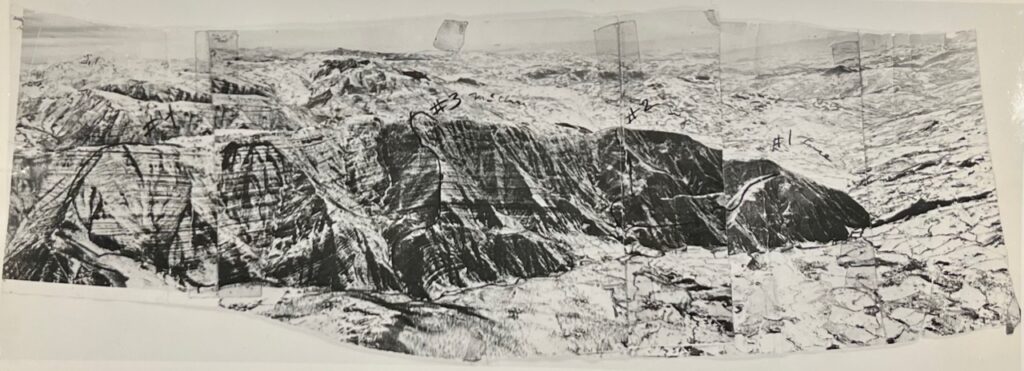

His had been the last route on Riva Ridge to go. Patrols had begun reconnoitering the other three routes in mid-January, when the mountain’s eastern slopes were plastered in snow and ascent was made easier by the crampons that had finally reached the battalion. But Route 3, which ascended the middle of the face to a subsummit known as Monte Serrasiccia, had remained a mystery. Interrupted by broken cliffs, precipitous gullies and rocky ledges, it was steeper than any of the other routes up the escarpment, and avalanches had scoured the line when they’d arrived, underscoring what even the most pedestrian of observers could discern. Route 3 was a mountaineering problem first, and a combat problem second.

John retrieved a ring-angle piton from the pile, his thick fingers tracing the contours of the words “U.S. AMES” that had been stamped into the metal. He’d used more than two dozen pitons to fix six pitches of rope up the route’s icy rock steps, and he wondered if he’d need more. He didn’t think he should: they’d spent the last two weeks behind the line in the small town of Lucca, studying maps and photos of Riva Ridge and climbing on the marbled walls of its quarries with fully laden packs. By the time they’d finished, even the 100 new additions to the battalion had accumulated enough skill—not to mention a taste of the unit’s esprit du corps— to get up the ridge without a problem. But with the exception of him and the members of a few other patrols, nobody in the 10th had had direct encounters with the enemy. They were green as Jackson’s Hole in June, and at dusk tomorrow, they would be his responsibility.

Yesterday, during his last recon, the Germans had sent up two flares to illuminate the ridge’s flanks. Did they have a sense of what was coming? If they discovered anyone in C company during the ascent and opened fire, he might need to deviate and find another line. That would take more pitons, and more rope. More gear would add to the load he’d have to carry—but compared to the responsibility of getting all his men to the top, the additional weight didn’t matter.

Plus, there was Ridge X to think about. C Company’s orders were to take Monte Serrasiccia and then clear Ridge X, a subsidiary point that provided the Germans with a natural route of approach they could use for counterattacks from the other side. If Riva Ridge were to be held, Ridge X had to be secured as well—and neither he nor anyone else hidden away in the stone farmhouses had even seen it.

A bitter gust of wind rattled the windows. The sound transported him back to the last time he’d laid out his equipment like this, in the summer of 1941, when he and Ed McNeill had stopped by a shallow lake in British Columbia to pare down the loads they’d bring with them on their six-week expedition to the Coast Range.

It had been the height of summer. Ducks had dotted the lake’s surface and the buzz of cicadas had filled the air as the engine of their Ford ticked in the sudden stillness. John could still remember the American Wigeons exploding from the water as he opened the car door, and the green-headed mallards that had remained, oblivious to their presence.

He could also remember the mix of excitement and anticipation he’d felt as he’d pulled their pitons from the back of the wagon, jangling them like metal fish on a fishing line. While Ed had coiled their climbing rope, John had laid the pitons in a row in the tall summer grass, then reached back into the Ford and pulled out his ice axes. He’d turned toward Ed, brandished it above his head, cut a step into the illusionary ice with the adze and seated his make-believe crampons into the resulting shelf before gazing skyward. “I… can see… the summit!” he’d bellowed heroically, shielding his eyes from the sun’s glare as he pointed his axe toward the sun. gazed heroically towskyward. Ed had laughed so hard he’d doubled over, dropping the rope to the ground. John could still remember the way the leaves of the aspen trees near the lake trembled in the breeze.

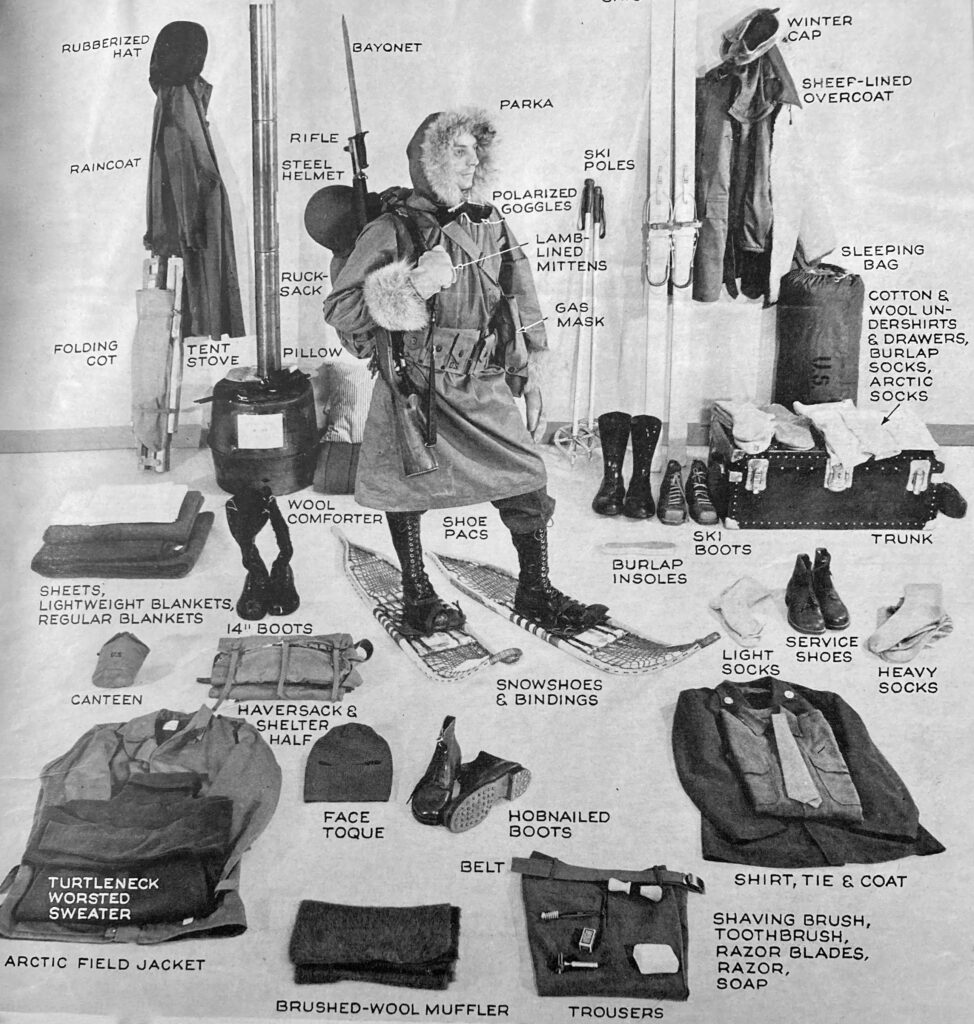

So much had changed since then, not the least of which was the gear. John and Ed had ordered their axes, along with their crampons, pitons, and carabiners, from Munich’s Sporthaus Schuster because no American companies in America made the sort of equipment they’d needed to tackle the Coast Range mountains. Their stove had been from Sweden, their climbing boots from England, their snow goggles from Switzerland. The manila fibers of their climbing rope had been imported from the Philippines. Now everything they would need for a similar expedition was made in the States, and much of it lay before John on the farmhouse floor, lighter, stronger and better than anything he and Ed had used before the war.

John was one of the lucky ones. Most of the gear and clothing that had been developed for the 10th Mountain Division had yet to arrive in Italy, and he and his fellow soldiers had spent the past month shivering through the freezing winter nights in Army-issue blankets and trudging through the January snows and the muck of the thaw in regular Army-issue combat boots, cursing whatever or whoever had held up the equipment they’d used for the past two years in Colorado’s Camp Hale. The rubber-soled mountain boots and nylon ropes and purpose-built pitons and hammers and crampons and axes that had finally arrived had gone to men like John, who had been tasked with leading night-time patrols on recon missions up Riva Ridge.

As the February thaw had set in, he’d been selected to figure out a way up Route 3. Of all the soldiers in the battalion, he was the best climber, and Route 3 was the only line the 86th had been unable to crack. He’d needed all his skills to find a way across the swollen river and up the tortured, steep-sided slopes, navigating the fluted shoulders, sandstone bands, sharp ravines and densely wooded mountainside without a light, lest the Germans on top see him and his patrol. And tomorrow, once night engulfed the valley, he would lead the men of C Company up the route to break Hitler’s Gothic Line and help end this godforsaken war once and for all.

A faded photograph of a young peasant couple with a baby looked down on John as he held the piton. Ed was on a Navy destroyer somewhere in the Pacific. John’s brother Grove had enlisted with the 10th the preceding summer; soon he, too, would be shipping out to join John and his fellow soldiers in the Apennines. And if tomorrow went as planned, when it was all over, the three of them would sail home and head west again, for Jackson’s Hole and the Tetons, or maybe another attempt at Mt. Waddington, or maybe even an expedition to the Yukon or Mt. McKinley, using the gear and clothing and food that they’d been testing for the past three years to get back into the mountains that lay an ocean and a lifetime away.

The window panes shuddered in the wind, shaking John from his reverie. He placed the piton on the floor, then retrieved two more from the pile, placing them precisely beside the first. He made another row for the clothing he’d wear on the climb. Though the days were warming in the valley, they’d be climbing at night, and they still expected icy slopes and deep snow and cold temps on top.

Mountain boots, trousers, field jacket, wool shirt, wool sweater, leather gloves, wool gloves, long underwear. An extra pair of heavy wool socks. No bedding, blankets or packs. One K ration. Extra ammunition. Take the stove, but leave the extra gas can behind. Leave the tent. Leave the ski parka, snow camo gloves, pants and pack cover. Take the canteen, compass and first aid kit. Handkerchief, helmet, pocket knife, flashlight, ski cap, notebook, pencil: one by one, John considered each item and moved it into one of the rows or returned it to the pile.

All he could remember from their stop alongside the lake were the forests of Sitka Spruce and Douglas firs that had stretched out behind it as far as he could see. “It goes on forever,” he’d marveled, his axes hanging at his sides.

Ed, his fine brown hair framing his cherubic face, had swiveled to take in the trees that had sparked John’s amazement. How boyishly handsome he seemed in John’s mind, how innocent, his lean frame skinny in Levis, the pantlegs rolled up at the cuff. The adventure that stretched out before them had seemed as endless as the forest.

John slipped his dog tags over his head. The contrast between the youthful exuberance he’d felt then and the responsibility of the present mission was as cold as the metal on his chest. Tomorrow, he would carry the safety of his soldiers as well as the contents of his pack on his shoulders. The climb would demand every ounce of his experience and training, and the strength and expertise of all 230 of his men.

He plucked a fourth piton from the pile, wrapped it in the extra pair of socks to keep it from rattling, and placed it beside the others as the light in the room slowly faded.

—–

A mountaineer’s reliance on his or her gear is absolute. High in the mountains, far from the safety of a rescue, the failure of one’s equipment can be lethal. Your stove sputters out on day three of a climb, and, unable to melt snow for water, you’re face to face with dehydration. A maelstrom of wind and rain tears your tent, saturating your sleeping bag, and now you’re hypothermic. A wet storm soaks your gloves, freezing your fingers, and you find you can no longer zip your jacket. Ten miles into an approach, your ill-fitting boots leave you crippled. A crampon strap breaks. Your rope cuts over an edge. The shoulder strap on your pack tears out midway up a multipitch climb, and you’re screwed.

On Riva Ridge, John and the soldiers of C Company would be even more reliant on their equipment, because malfunction could spell mission failure as well as death.

When John and Ed McNeill paused beside the lake in British Columbia, almost every part of their kit was state of the art by design. Their two-person, twelve-pound tent and their six-pound sleeping bags were both made by Woods Manufacturing Company, the British firm that had supplied the 1938 American K2 expedition with some of their equipment. Likewise, John’s boots had been made by Lawrie Boot Makers of London, and he’d placed rows of imported Swiss edge nails that cost $.10 each around the edges of the soles. Their Swedish made Primus stove was the best money could buy. John’s wool knickers were from Switzerland. Their 100-foot climbing rope was made from manila, a natural fiber named for its place of origin in the Philippines. Their Aschnebrenner ice axes were from Austria; their eight-point Eckenstein crampons had been made in Courmayeur, Italy. Their piton hammers, rock pitons, ice pitons and karabiners had all been made by the August Schuster Munchen company, part of the same family that had opened Sporthaus Schuster in Munich at the start of the first world war. John and Ed had ordered much of their climbing equipment from Sporthaus Schuster for a simple reason: it was one of the few places American climbers could buy equipment before the war.

Fast forward three and a half years to Riva Ridge, and Sporthaus Schuster was no longer doing business with America. Fortunately for C Company, John and his comrades were no longer dependent on European companies for their equipment: every aspect of production, from design to sourcing to testing to manufacturing to distribution, was now American made.

The story of how the 10th Mountain Division’s gear and clothing underwent such a rapid evolution is critical to our tale, because it not only had profound implications for the soldiers’ ability to train for cold-weather and mountain offensives like Riva Ridge—it became the foundation of America’s outdoor recreation industry after the war as well.

Nobody has ever erected a statue to honor a committee; but perhaps, when it comes to the 10th Mountain Division’s equipment, an exception should be made. Or five exceptions, to be precise: two for the civilian skiing and climbing committees that proposed, developed and tested materiel on the mountain troops’ behalf, two more for their functional equivalents within the Army, and a fifth for the Quartermaster Corps, the branch of the Army that produces, acquires and supplies everything its soldiers need to fight a war. And should said statues ever come to be erected, one could argue that they be best positioned in close proximity, or better yet, in a circle, for the members of all five entities worked in a symbiotic collaboration that succeeded where none of them working independently could have prevailed.

First up were the skiers, with their indefatigable leaders, the National Ski Association’s Roger Langley and the National Ski Patrol System’s founding director, Minnie Dole, out in front. In November 1940, the NSA had established its National Volunteer Winter Defense Committee to (quote) “assist the army by furnishing advice in technical training and equipment selection, and to assist in home defense by becoming familiar with local terrain in the northern states.” Inspired by the camo-clad, cross-country skiing Finnish guerilla soldiers and their fight against the invading Russians during the Winter War of 1939-1940 , home defense had served as the originating impulse for Dole and company’s lobbying efforts for a ski troop. Though home defense would soon give way to the broader vision of an offensive strike force on skis, the equipping and training of the troops would remain one of the committee’s priorities.

And the Army needed their help.

“[M]ountain and winter warfare demands many types of specialized equipment,” wrote Major John Jay in his history of the mountain troops, “most of which were unknown to the United States Army in 1940. Items such as mountain boots, climbing ropes, pitons, piton hammers, crampons, and ice axes were needed for summer mountain work. Winter-time called for skis, snowshoes, mohair climbers, ski trousers, ski boots, parkas, goggles, rucksacks, sleeping bags, tents and the like. At all seasons the mountain trooper needed rations of food of a dehydrated nature. All these items were available in small quantities and various qualities for civilian sport use, but few of them could be adapted to military needs without substantial changes and improvements. Producing them in mass volume was another problem that then had to be solved.”

Here’s Ninety-Pound rucksack advisory board member Sepp Scanlin.

26:14: [Sepp Scanlin interview]

Sepp Scanlin: “The famous quote is essentially, when they have the first meeting, they say, well, yeah, we’ve got a manual for this. And they pull out the 1918 manual for Alaska winter clothing. That really shows you how they hadn’t really invested in this problem. They saw the clothing issue as one heavy layer that you wore on garrison duty, primarily in the new territory of Alaska. There was no accounting for movement and what we would consider operational use of people and material in cold weather. It was essentially to survive in garrison environments or you know, frontier outposts, for lack of a better term. So they were woefully unprepared. Even if you look at the manual, the equipment they had back then was frighteningly limited in what it provided to the soldiers at the time.“

And here’s advisory board member Llance Blyth:

27:04: [Lance Blyth interview]

Lance Blyth: “Armies generally do not like to fight in the winter. It’s so hard—just the sustainment piece, moving food and supplies forward, bringing the wounded back—that they typically looked at winter as something you did static.

“When they did think about very cold weather, extreme cold, they generally thought in terms of being in Alaska and that meant they were lots of fur, lots of leather layers Very effective, no question. But no way could they possibly equip an entire army with that sort of stuff. So by 1940, when they’re seriously considering it—realizing they might have to defend Alaska, may need to send forces to defend Newfoundland or Greenland. If Great Britain goes down—this of course the battle of Britain’s raging; there’s no guarantee that Britain will survive—they begin to look around and begin to seek, honestly seek outside assistance.“

In late November 1940, the NSA convened its Defense Committee at La Crosse, Wis., to discuss the Army’s needs. General Marshall had assigned Lt. Cols. Charles E. Hurdis and Nelson M. Walker to attend the meeting. “[It] is interesting to note,” wrote Jay of the gathering, “that these two officers, who had come to seek advice and cooperation for this new Army venture from the experts of the ski world, soon discovered to their amusement that even the experts couldn’t agree on such fundamental issues as the type of binding to be used.”

Go to any local bar in any ski town in America on a Friday night in January, grab a microphone and ask the boisterous patrons what’s the best type of binding currently on the market and you’ll instigate a discussion impassioned enough to inspire fisticuffs. Climbers and skiers alike will happily spend at least as much time arguing the merits of their preferred gear as they will actually using it, a personality tic we apparently inherited from our forebears.

Here’s the problem. If America were to develop the equipment and clothing necessary to fight in the mountains, it needed designs sanctioned by experts—but no such sanctioning body existed within the civilian communities.

29:09: [Lance Blyth interview]

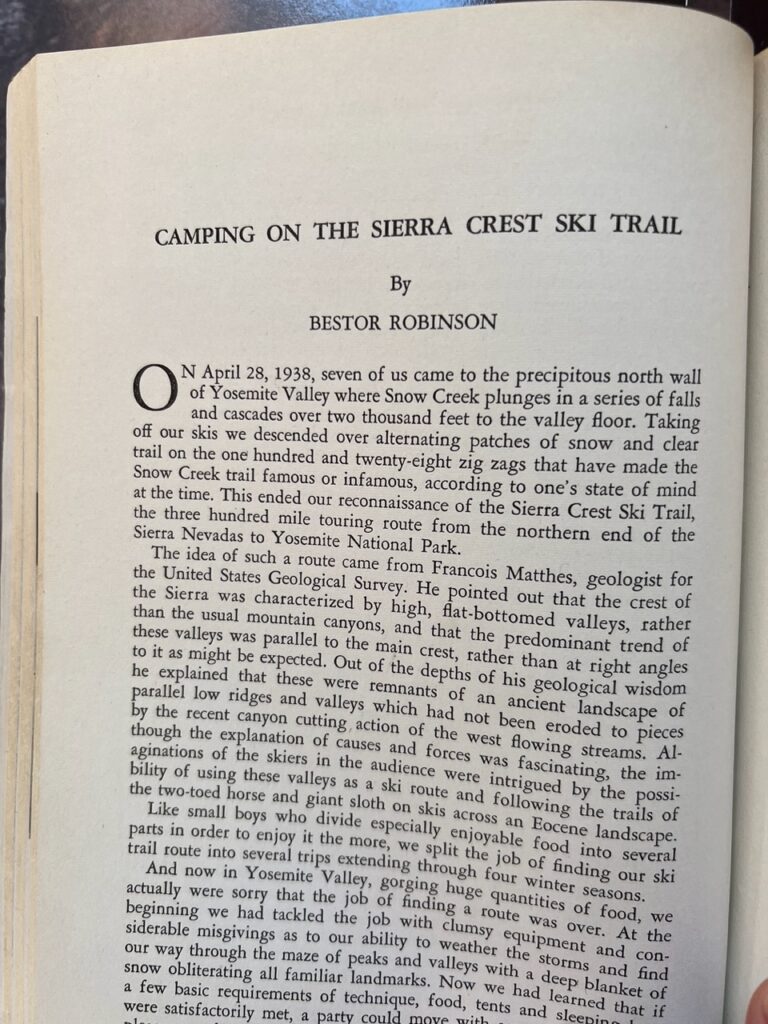

Lance Blyth: “The National Ski Association—Roger Langley is the president—realizes, oh, if we’re gonna do this, we need to be organized. So he sets up a committee, the equipment committee, and he asks NSA member Bestor Robinson to chair it.“

You’ll remember Bestor Robinson, the UC Berkeley and Harvard Law-educated lawyer and Sierra Club Director who partnered with future governor of California and Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court at his father’s law firm. In the mid-1930s, Robinson had been part of the innovative group of Sierra Club climbers that, under the direction of the analytical brilliance of fellow attorney and environmentalist Richard Leonard, had evolved the art of roped climbing via a methodical study of belaying techniques and fall dynamics. The insights gleaned from their experimentation, coupled with cutting-edge equipment they purchased from Sporthause Schuster, allowed Robinson, Leonard and their peers to establish technical ascents harder than anything previously climbed in the US, including new routes in Yosemite Valley’s Cathedral Spires that stood as the opening chapters of American bigwall climbing.

Innovation is disruptive, and the old guard of American climbing was quick to condemn the Sierran climbers’ reliance on pitons and advanced aid techniques, which they considered to be unsporting if not downright immoral.

Robinson, who was as opinionated as he was talented, did not share their concerns.

When he and Leonard, together with fellow Sierra Club members David Brower and Raffi Bedayan, parlayed their European tools and new-found expertise into the first ascent of Shiprock, a 500-meter volcanic plug in the Four Corners area of the Colorado Plateau, Robinson expressed the team’s righteous triumph in an article in The American Alpine Journal.

“I’m a rock engineer and proud of it,” he wrote. “I climb mountains for the same reason that the purists do, because of the sheer joy of accomplishing the difficult. To use pitons for direct aid on a pitch that can be climbed without is to destroy the difficulty that is the basis of the sport. But show me the man who has hung over space suspended by a chest loop from a piton, meanwhile searching for a narrow crack that will admit another, all the while squirming into a position that will enable him to swing the pesky hammer and trying not to get tangled in his ropes – show me such a man who has led real overhangs on pitons, which he has put in, and you will find an enthusiast for rock engineering who will tell you that such a job is more difficult than climbing [one of the European testpieces of the day].”

As John Middendorf said of the Shiprock ascent in Mechanical Advantage, his brilliant two-volume study of the evolution of climbing tools, “It was the most technological ascent in North America at the time, and on par in difficulty with the aid routes in Europe….”

32:04: [Lance Blyth interview]

Lance Blyth: “Now Robinson is connected. Robinson is not only a member of the National Ski Association, he is also a member of the American Alpine Club, and he’s also a member of the rock climbing section of the Sierra Club out of the Bay Area in California. They start adding more people into this committee as it goes on.“

Grand Poobahs of American skiing that they were, Dole and Langley were appointed to the committee as members ex-officio, and our old friend Rolf Monsen, the Norwegian-born, cross-country skiing and ski jumping Olympian who we first met way back in Episode 3 when he was teaching soldiers to ski on the slopes of Lake Placid’s Whiteface Mountain, was appointed as well. And importantly for our story, so was the American Alpine Club’s vice president Walter Wood, Jr.

We’ve met all these characters before. But this is where they all start coming together, to work in concert on the mountain troops’ behalf.

32:56: [Lance Blyth interview]

And since they’ve got Wood, they also have access to all the work that Carter’s been doing.

He’s referring to H. Adams Carter, the 26-year-old American climber we profiled in our last episode who single-handedly created the foundation for America’s mountain warfare doctrine with his translations of foreign material.

33:14: [Lance Blyth interview]

Lance Blyth: “And so they go through this for a couple months and they’re looking for a system of how you would supply an army unit. Now they’re thinking winter and skis—right now they’re not doing the mountain side, they’re doing the ski side. How would you do it?

“Robinson says, look, no other model’s gonna work for us. The Europeans are in Europe where there’s lots of buildings, villages, barns, huts up high that you can use for shelter. You know, the Swiss built fortifications high in the mountains, so their forces have a place to live in the winter. We’re not gonna have that in North America. The Nordic countries used a lot of tents, but they had horse drawn sleds they could use. So we can’t really look at the Finns and they’re in relatively flat forested areas, not steep mountains.

“They looked at mountain expeditions; those used porters to build up base camps. And the Arctic guys used dog sleds and dog teams to bring in supplies. And Robinson said, look, there aren’t enough dogs to supply an army unit. So Robinson then determined that what he needed was a North American system, an indigenous system.

“And he just happened to have it, for the Rock Climbing section—kind of the early big wall climbers in Yosemite—would shut down every October or so and reform as the ski mountaineers. And because the Sierra Nevadas have a maritime snowpack—it’s not as deadly as it is for the Rockies—they would go into the mountains, they would ski in with a pack, they would camp on the snow, they’d climb up a mountain and they’d ski down.

“And they called it ski mountaineering. But in many ways it’s the beginning of backcountry skiing today. But he figured out that what the army needed was a way for guys to live out of their packs for several days in the mountains on the snow. And they had worked very hard to develop some gear for that. And they had published a lot of these articles about how to go about doing this. So they had a lot of information.“

We’ve mentioned that Robinson had developed a 300-mile ski route through the heart of the Sierra Nevada in the late 1930s. What we didn’t mention was that he’d made much of the equipment necessary for the endeavor on his own.

He didn’t have much of a choice. His adventures were so futuristic, the equipment needed to execute them simply didn’t exist. Still, the depth of his tinkering sheds light on the insight and perspective he would bring to bear on the matter when, four years later, the country needed to begin outfitting its first mountain division from scratch.

Take sleeping bags. As Robinson recounted in an article in the 1938 American Ski Annual, he and his partners worked out the governing principles of a quality design over the campfire:

- The filling must be highly compressible so as to reduce the bag to the minimum bulk when packed.

- The bag must have the maximum insulating value for unit of weight.

- Since radiation of heat is directly proportionate to surface area, the bag must be form-fitting.

- The design must be such as to prevent effectively the loss of warm air and the introduction of cold air around the shoulders.

Said principles dictated the use of down and a form-fitting “mummy case” design. But since such sleeping bags were not on the market, Robinson wrote, “we made our own and were surprised to find that an evening’s work completed the job.”

In case it has been a while since you gathered with your friends for an evening’s sewing circle as you made your own sleeping bags, here’s how to do it.

“…[T]he bag,” wrote Robinson, “should be made of two layers of very lightweight closely woven Egyptian sail cloth or balloon cloth, weighing not over two ounces per square yard. All seams and edges, except at the foot, should be sewed together, thus forming ten tubes. … A 2 1/2 pound bag of down should be purchased; the blower and suction hose attached to the family vacuum cleaner, placing the suction end in the down bag, and the blower end into one of the tubes, and gradually withdrawing it as the tube is filled. The foot end of the two must be held tightly around the blower hose, else a splendid imitation of a high sierra blizzard ensue. Equal distribution of down between the 10 tubes can be secured either by estimate or by continuously weighing the bag of down. After the blowing is completed, the lower ends of the tubes are sewed together.” The finished product, according to Robinson, “should weigh 4 pounds and roll into a bundle 8” x 13“.”

What about tents? Mountaineers had been relying upon them for years, but Robinson was nothing if not confident he could better any design out there, so he made his own tent as well.

Or rather, he made two: a bivouac tent that could be adjusted in various configurations to provide shelter for two; and a second, larger tent that could accommodate three people sardine style, when blizzards necessitated cooking inside. Such an approach resulted in a total weight of six and a quarter pounds for both tents, or one and a quarter pounds per person when distributed among a party of five.

When I was editing Alpinist Magazine, we had a saying: It takes a big ego to climb a big mountain, and Robinson’s sense of self, honed by his time before the bar as well as expeditions in the Sierra Nevada, Mexico, Canada and Alaska, was, by the time of the war, rounding into top form. He was smart, talented and confident of his own expertise, and these attributes extended to his pronouncements on the proper materials to use for his tent’s construction as well.

“The tent must be constructed not merely of water repellent, but of thoroughly waterproof, materials,” he intoned in his essay. “Most of our group prefer two ounce cotton balloon cloth coated with neoprene and treated to prevent rot and mildew. Neoprene, or chlorinated rubber, has the impermeability, toughness and elasticity of rubber, and does not disintegrate under sunshine, or rot or dissolve in contact with petroleum derivatives. Its smooth outer surface sheds snow and prevents the adherence of ice, the latter being a matter of no small importance when it comes to breaking camp and carrying the increased weight of an ice-coated tent.”

Ah, but there is a fine line between brilliance and arrogance, as we shall soon see, and Robinson’s prodigious intellect was also his Achilles heel. Cotton balloon cloth coated with neoprene does shed snow and is tough as nails; but it also doesn’t breathe, a consideration Robinson, for all his talents, refused to accept as a reasonable argument against its adoption. The repercussions of his obstinacy would affect both the mountain troops and his standing among his own peers.

Still, if you needed a person to get the mountain equipment ball rolling, Robinson was a pretty good place to start.

40:04: [Lance Blyth interview]

Lance Blyth: “So after a couple months of doing all this study and then determining that what he did was the way to go, Robinson does go test it. He goes in April of 1941, takes about 20 ski mountaineers, including a young editor for the University of California press by the name of David Brower, back into the mountains, the Little Lakes Valley and the Eastern Sierras west of Bishop.

“And they go in in April, right into a spring storm. But they’re there to test gear. They test whole bunches of civilian gear. They have, let’s see, skis from Northland. They had boots by LL Bean. They had sleeping bags and tents from Abercrombie and Fitch. They had clothing from Montgomery Ward and they tested all of these things.

“When they come back out, two things happen. One Robinson goes to Brower, goes to the Sierra Club and says, we need to write a manual. We need to put all the stuff we know into a book for other ski mountaineers to use and for the army to use. And so David Brower begins to edit this at the University of California press. And this will become that manual of ski mountaineering that when you take Carter’s work and add in the manual of ski mountaineering and then what the American Alpine Club’s contributed, that becomes the basis again for all mountain warfare and cold weather warfare doctrine to today.

“Robinson also sits down and writes up a whole bunch of tentative specifications of what you would need. He sends a whole bunch of stuff back to the war department. They pass it down to the quartermaster general who’s responsible at this time for all this procurement stuff. And they take it and they begin to run with it.

“And by summer of 1941, before there’s even a mountain infantry battalion, there are specifications for rucksacks, sleeping bags, reversible ski parkas, ski trousers, gators, headbands, felt insoles, pocket knives, mittens, ski tents—his design—ski caps over white trousers for camouflage, repair kits, poles, bindings, boots and waxes.

“By the summer of 41, they had a really—turns out to be a pretty good set of specifications, because most of these do not change. They really nailed it. These skiers, these backcountry skiers in my opinion got it pretty right. So the NSA equipment committee, also thanks to Walter Wood, noticed that, oh, the American Alpine Club had a committee and they did state that they did go ahead and coordinate between the two.“

Which brings us back to the climbers.

“In the Fall of 1940,” Bob Bates wrote in his autobiography, The Love of Mountains is Best, “Bill House, Charlie Houston and I asked the American Alpine Club to discuss the part it might play in national defense. Ad Carter and Walter Wood were also active.”

The 10th’s ability to break Hitler’s Gothic Line was made possible by men like John McCown and the specialized training and advanced gear developed on his behalf. This in turn was facilitated by figures like Bates and House and Carter and Wood. They’re considered secondary characters in the Division’s broader narrative, but they were part of the backbone of its success, and their contributions were a function of their singular lives.

They also offer a microcosmic study of a pivotal moment in the country’s history. The passage of time has blurred the details of America’s role in World War II. To appreciate its true significance, it’s necessary to consider the countless individuals who, working in concert, determined the war’s outcome. In telling the 10th’s story, I’m focused on the climbers, in part because I feel their impact has been overlooked, and in part because their contributions transcended the war to affect a cornerstone of society that many of us take for granted today.

Your appreciation of their contributions hinges on your understanding of the experiences that shaped their perspective, which is why I’m examining them closely in this episode—starting with Wood and Bates.

Walter Wood Jr. was a globe-trotting, mountain climbing geographer who’d helped map the Kashmir-Tibet border in 1929. In the 1930s, he’d participated in expeditions to Colombia, Panama, Guatemala, Mexico, Greenland and the Grand Canyon.

His true love, though, and one of the primary focal points of both his mountaineering and scientific interests, were the St. Elias Mountains that straddle the Alaska/Canadian Yukon border and that we described in detail in our last episode. In 1935, he’d participated in the first ascent of Mount Steele, one of the Yukon’s highest and most inaccessible peaks. In 1939, he’d led an exploratory expedition that mapped the range by aerial photography.

Wood had begun working on plans to return to the area with someone as familiar with it as he was. By now, you, dear listener, are familiar with him too, for his name is Bob Bates, the endlessly enthusiastic, unfailingly affable climbing partner of H. Adams Carter, and he has been part of our story since Episode 1.

Bates was born in Philadelphia in 1911, and he grew up, like Carter, in comfortable circumstances. Academia ran in his blood: His father was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and his mother, a Radcliff-educated teacher, imbued in him her love of literature and wildflowers as well as the outdoors. Like Carter, Bates climbed his first mountain at the age of five, and spent the summers of his childhood exploring the brooks and paths and game trails of New Hampshire’s White Mountains and the cliffs and ledges of the Maine coast with equal abandon.

Any life lived long enough is marked by tragedy, and in 1925, when Bates was 14 and attending the William Penn Charter School, John McCown’s alma mater, he lost his beloved mother to pneumonia. The death shocked him and devastated his father, who sent him to board at the more academically rigorous Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. Bates buried himself in his studies. Whether the immersion helped him through his grief is unknown, but it did gain him entry to Harvard, where he began his coursework in the fall of 1929, where he soon became part of the Harvard Mountaineering Club.

One of the first people he met at the Club was the 21-year-old Bradford Washburn, who was fresh off a first ascent of the 4,000-foot north face of the Aiguille Vert in the French Alps, which he’d climbed in a single day with two young guides. The climb had led to Washburn’s induction into the Club Alpin Francais’s Groupe de Haute Montagne, where he was the youngest American member. He was also a member of the Explorers’ Club in New York, and he’d published a popular book, Among the Alps with Bradford, in 1927, when he was just 17, using the proceeds to pay his way through Harvard.

“What he knew about climbing was endless,” Bates would later write of his new friend. “He was excellent company, too, with boundless energy and a good sense of humor.” Bates soon found himself swept up in Washburn’s adventures, which included the explorations of Alaska’s Fairweather Range just south of the St. Elias mountains.

Bates and Washburn’s attempts on Mt. Crillon in 1932 and 1933 introduced them to Carter and Charlie Houston, who, along with Terry Moore, would become legendary as the Harvard Five. All of them were as serious about their studies as they were climbing, and in 1934 Bates was forced to decline a return engagement with Crillon in favor of completing his master’s degree at Harvard. As difficult as that must have been to the ambitious young mountaineer, doing so prepared him for the academic career he would pursue for the rest of his life. It may have also introduced him to John McCown. “[T]o get a feel for teaching and to learn whether it would be something I wanted to do as a career,” Bates wrote in his autobiography, The Love of Mountains is Best, “I also did some practice teaching at Penn Charter, my old school.” McCown would have been a sophomore at Penn Charter at the time.

Bates’ familiarity with the Yukon interior began in February 1935 with the mind-boggling, three-month-long exploration of the St. Elias mountains we detailed in our last episode. but it was an ascent two years later that would solidify his appreciation for the area while establishing him and Washburn as two of the most intrepid and resourceful mountaineers of their generation.

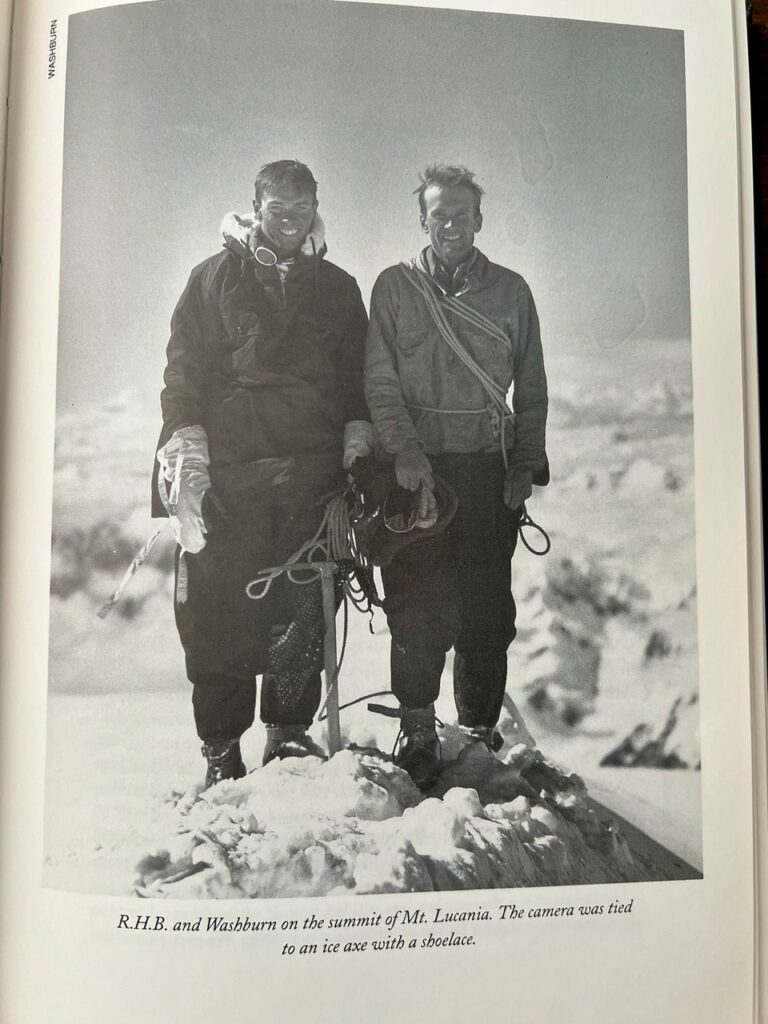

In 1937, the 17,000-foot Mt. Lucania was the highest unclimbed peak in North America. The pair put together a four-man team to make its first ascent only to see their numbers cut in half before they could begin the climb.

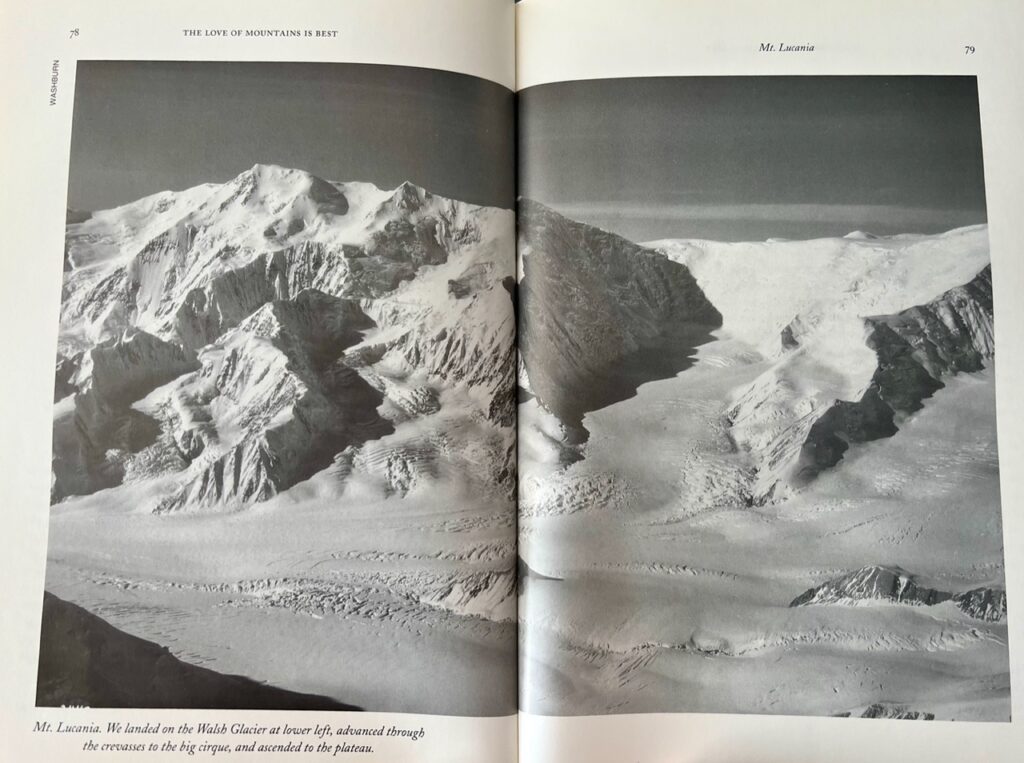

As David Roberts recounted in Escape from Lucania, his narrative of their harrowing ordeal, a bush pilot flew Washburn and Bates to the Walsh Glacier at the foot of their objective only to discover “that freakish weather conditions had turned the ice to slush. Their pilot was barely able to take off again alone,” he wrote, “ and there was no question of returning with the other two climbers or more supplies. Washburn and Bates found themselves marooned on the glacier, more than a hundred miles from help, in forbidding and desolate territory. Eschewing a trek out to the nearest mining town — eighty miles away by air — they decided to press ahead with their expedition.”

Doing so required paring down their loads. Given that they had packed for a team of four, this was relatively easy to do. Leaving behind a tent, clothing, food, and two cameras, they cut the weight of their equipment to 300 pounds. They had 50 days supply of food, a Logan tent, a primus stove, two saucepans, 15 gallons of gas, two heavy … sleeping bags, two air mattresses, part of a tent for use as a tarp, a minimum of warm clothing, Washburn’s 9 x 12 cm Zeiss camera and film packs. “Our gear was heavier than clothing and equipment used today,” Bates would later write. “The tent weighed 15 pounds dry and 22 or 23 pounds wet or with the bottom iced up. The… sleeping bags weighed at least 12 pounds each dry. We had no down clothing. The stove and fuel containers were heavy, and our pack boards weighed 6 pounds apiece.”

Roberts, a veteran of the Harvard Mountaineering Club as well, would go on to become a formidable Alaskan climber in his own right. His appreciation of the pair’s resolve was grounded in a first-hand understanding of the magnitude of their undertaking. In utter isolation, they made their determined drive toward Lucania’s summit, he wrote, “under constant threat of avalanches, blinding snowstorms, and hidden crevasses. Against awesome odds they became the first to set foot on Lucania’s summit, not realizing that their greatest challenge still lay beyond. Nearly a month after being stranded on the glacier and with their supplies running dangerously low, they would have to navigate their way out through uncharted Yukon territory, racing against time as the summer warmth caused rivers to swell and flood to unfordable depths. But even as their situation grew more and more desperate, they refused to give up.”

To be honest, they didn’t have much of a choice: to give up would have been to die. But they did have a choice in how they made the arduous trek home, and the fact that they decided to add the second ascent of the adjacent Mount Steele along the way speaks volumes about their audacity. Jettisoning items of equipment as they went, they slowly whittled down their loads from 150 pounds a piece to 90 to 75 to sixty, the absolute minimum they needed to survive. By the time they staggered back to civilization, they had accelerated their apprenticeship as mountaineers. They had also gained a deep appreciation of the weight and functionality of their equipment . Three years later, this expertise would come in handy when their country began to prepare itself for war.

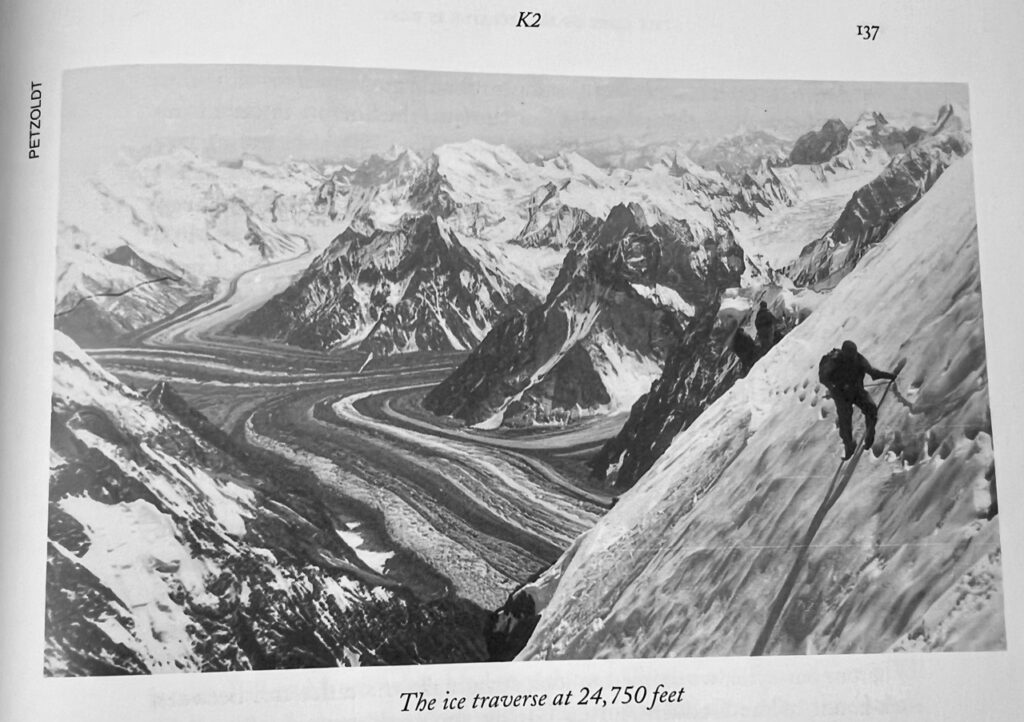

Bates’ adventures in Alaska and the Yukon had served as his baptism in expeditionary mountaineering, but it was his attempt, the following year, on the world’s second highest mountain that marked his arrival on the global stage. Pakistan’s K2 had first been attempted in 1909 by the Italian Duke of Abruzzi, and the expedition’s photos of the magnificent east face had riveted alpinists the world over. Among those transfixed was Fritz Weissner, a short, stocky German-American with an engaging personality, a wide and friendly grin and a skill set orders of magnitude more refined than anything North America had ever seen.

The premise of John Middendorf’s Mechanical Advantage is that advancements in mountaineering are made possible by the evolution of gear. “One of the most interesting periods of climbing tool development,” he wrote, ”occurred on the steep rock of the Eastern and Western Alps during the early decades of the 20th century, when war, pandemics, and economic depressions were rife.”

Like a number of his fellow emigres, Weissner had come to the US in 1929 to escape the economic fallout of the Treaty of Versailles, and he brought his remarkable free climbing skills with him. He’d honed those skills on the steep rock of the Eastern and Western Alps during the early decades of the 20th century, and they had been made possible in part by advancements in climbing tools that were years ahead of American products.

Once in the States, Weissner continued to order his equipment from companies like Sporthaus Schuster. As his athletic abilities gained him entry into the inner sanctum of American climbing, his new partners had the opportunity to appreciate the superiority of his German and Austrian equipment. This in turn would go on to influence American mountain troops when those same partners were put in charge of developing equipment for the 10th.

In 1932, Weissner had participated in a German expedition that had reached an altitude of 7000 meters on the 8100-meter Nanga Parbat, and the Italian photos of K2 had stirred his imagination.

Countries had begun staking out claims on the world’s highest mountains in the 1920s. The Brits focused on Everest. Germany set its sights on Nanga Parbat. America—by which I mean The American Alpine Club, epicenter and enclave of America’s best climbers—had resolved to climb K2. Weissner’s technical mastery coupled with his experience at altitude convinced the Club that he should lead the effort, and it helped him procure the necessary paperwork for an attempt.

Wiessner had established a chemical business when he came to the US, the most notable product of which was a ski wax he dubbed Wonderwax—and yes, this does tie into our story. When he bowed out of the trip, citing professional obligations, the AAC asked Charlie Houston to find a route by which K2 might be climbed instead. Houston had invited Bates. “By this time we felt competent to climb any peak in Alaska,” Bates recalled, “but, of course, K2 was something else. This was the big time! It would test us to the bone.”

K2 was, and is, the world’s most formidable mountain. While Everest is some 800 feet higher, K2 is steeper, more remote and far more technically difficult. As Washburn recounted in the pages of The American Alpine Journal, “When, in the spring of 1938, the first American Karakoram Expedition sailed for India and announced this peak as its objective, experienced alpinists the world over shook their heads in knowing disapproval. Any mountain declared impregnable by the Duke of Abruzzi was no fit place for a party of youthful Americans to test their mettle.”

Joining Bates and Houston, who were 27 at the time, were two climbers we’ve previously met. Bill House was 27 as well. Paul Petzoldt was thirty. Both would go on to serve key roles on behalf of the 10th Mountain Division.

House, who had graduated from the Yale School of Forestry, was part of the new school of American climbing that had begun to arise most notably in California with Leonard, Robinson and the Rock Climbing Section of the Sierra Club. While the Harvard Five had mastered expeditionary mountaineering, the form of climbing they were best at entailed logistically complicated trips to remote objectives. They were expert cold-weather survivalists and snow camping maestros, but their ascents were predominantly snow climbs on less than vertical slopes, and nowhere near the technical levels being developed on the west coast.

House’s inclinations had more in common with the piton-protected adventures of the Sierra Club climbers than it did the exploits of more traditionally inclined mountaineers like the Harvard Five. At Yale, where he was a leader of the Yale Mountaineering Club, he’d become enamored of what we now call “buildering”: scaling the sides of campus buildings, largely at night to avoid detection. Buildering entails a far more dynamic form of movement than the interminable snow plods of the mountaineers, and it allowed House to envision what it might be like to apply similar techniques to steeper terrain.

Ascents of the Grand Teton in 1932 and in Colorado’s San Juan Needles and Wyoming’s Big Horn mountains followed. This in turn led him to the company of Wiessner, who shared a similar, if more sophisticated, perspective, and who had his eyes set on the great unsolved problem of the 1930s: Canada’s Mt. Waddington, the same mountain that would inspire John McCown and Ed McNeill’s 1941 expedition to the Coast Range.

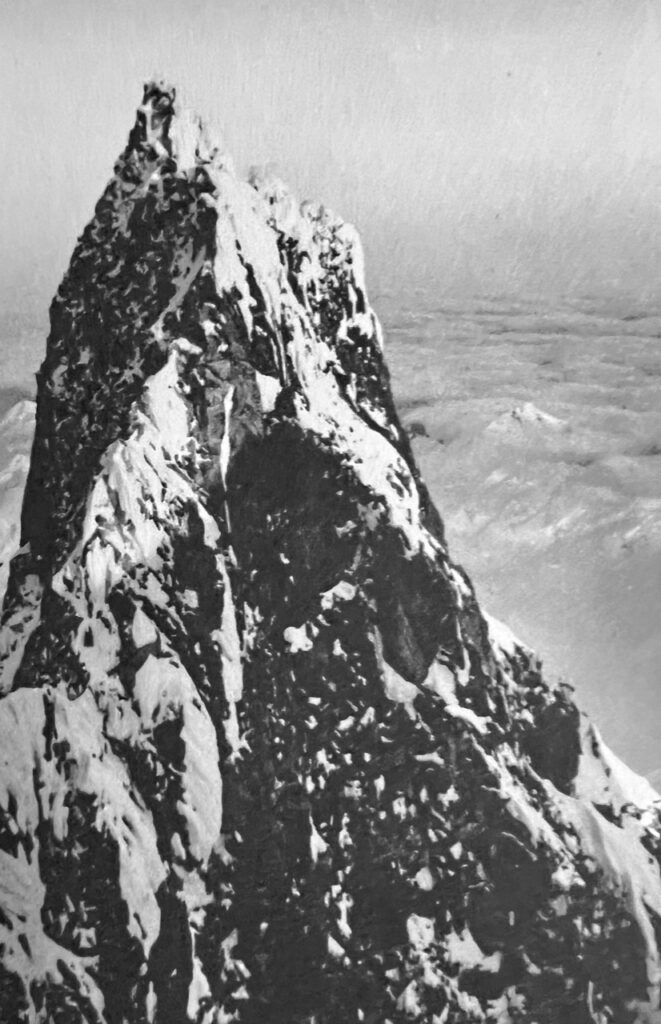

What Waddington lacks in elevation — it’s a skitch over 13,000 feet high, lower than the Grand Teton—it more than makes up for in both difficulty and beauty: the needle-like granite summit, often coated in gossamer wings of rime, is defended by serrated ridgelines and vertical walls, not to mention icefalls, crevasses, glaciers and icefields, dense forests, deep river valleys and the coast range’s notorious weather. Wiessner and House were far from the only climbers interested in climbing it. By the late 1920s, Waddington, also known as Mystery Mountain, had come onto the radar screens of climbers the world over. The mountain’s complex architecture was compelling precisely because it would require mastery of all of climbing’s disciplines, as well as the vision for how to apply them safely in the remote reaches of the Coast Range. It would also require proficiency in the latest and greatest gear.

In 1935, fresh from their success on the “impossible” summits of Yosemite’s Cathedral Spires, Leonard and Robinson decided to give it a go. Assuming they could overcome the mountain’s technical defenses with their advanced skills as well as the equipment they’d ordered from Sporthaus Schuster, they traveled north with David Brower and four other disciples of the Sierra Club’s Rock Climbing Section only to be turned back by the range’s horrendous weather and Waddington’s rugged glaciation. They returned the next year with more people and more equipment, but the conditions and their relative unfamiliarity with alpine terrain thwarted their aspirations once again.

Their equipment list speaks to the evolving understanding of what it would take to climb such a mountain. For their 1934 ascent of Yosemite’s Higher Cathedral Spire, they’d used 55 pitons and 13 carabiners. As Robinson noted, their equipment for Waddington included one hundred twenty pitons, as well as carabiners, piton hammers, crampons, ice axes, snowshoes, tents, sleeping bags and the hundreds of other items necessary for a self-sufficient expedition.” Climbing such a mountain, he continued, would likely require “The Bavarian two-rope technique for overhangs, pitons for direct aid, rope traverses, and other phases of technical rock climbing.” In other words, Waddington would require the most advanced techniques and equipment available.

After the Sierra Club climbers failed, the weather cleared, and Weissner, who had gained American citizenship the year before, was in position with House for their shot. Their expedition had been put together under the auspices of The American Alpine Club. Similar to the Sierra Club attempt, it relied on European gear—but Weissner, who had learned to climb in the Alps, had a much different perspective on how to use it.

The Sierran climbers approached Waddington as if it were an ice-shrouded big wall. Weissner and House approached it as if it were an alpine objective. Weissner had learned that to climb efficiently and safely in the mountains required a light and fast approach. Accordingly, their rack consisted of 18 pitons, 8 carabiners, two piton hammers, a lightweight, supple 35-meter lead rope, a 90-meter, eight-millimeter rappel line, slings, two pairs of ten-point crampons, ice axes, hobnailed boots, and Weissner’s rope-soled climbing shoes.

Ascending a couloir the California climbers had deemed unacceptably dangerous, they accessed the technically difficult upper sections of the route, which Wiessner overcame in part by standing on House’s shoulders. House followed Weissner’s leads with a heavy pack, and, after 13 hours of technical climbing, the pair arrived on Mystery Mountain’s elusive summit. The descent, which took another 10 hours, required all their skill, pitons and slings, and proved to be the most dangerous part of the climb. By the time of their successful ascent, the mountain had turned back 16 teams, including those led by Leonard and Robinson.

Weissner and House’s climb not only proved the merits of a light and fast approach in the mountains; it gained the pair a rarified renown, as well as entry to attempt Devil’s Tower, a monolithic intrusion of igneous stone that rises abruptly from the Wyoming prairies in a steep-sided cylinder. The vertical columns and hexagonal pillars of its symmetrical walls were so imposing, the local rangers had prohibited anyone from climbing it less they die in the attempt. The pair succeeded, with Weissner again leading the way, and when Bates and Houston met House at the American Alpine Club in New York, they asked him to join them on K2.

During the Depression, jobs were scarce and food lines were long. Following his graduation, House had landed work as a forester—no mean feat. The invitation, wrote Bates, “meant nearly a six-month commitment of his time: a month to get to India, a month to trek 350 miles into the mountain, six weeks on the mountain and the same to return, with a little time for emergencies.” House didn’t blink. As Bates recalled, “He gave up his job and was told never to return.”

Petzoldt’s inclusion on the team was almost an afterthought, the suggestion of their first choice, Bill Loomis, who had climbed with Petzoldt in the Tetons and recommended him as a first-rate mountaineer. “The worthies of the American Alpine Club in New York frankly doubted whether ‘this Wyoming packer and guide’ would fit in socially with the others and comport himself as required in the company of their British and Indian hosts,” wrote Maurice Isserman in his book, Fallen Giants, but though Petzoldt, a ranch kid from Twin Falls, Idaho, may have lacked the polish and college degree of his wealthy teammates, he made up for it with his mountaineering acumen, not to mention his prodigious strength and oxlike tenacity.

House and Petzoldt added a perspective to the team that Bates and Houston simply didn’t possess. While the Harvard climbers had become exceedingly proficient at organizing expeditions and operating for extended periods of time in cold and inclement weather, House’s love of steeper climbing had led him to develop his own pitons to facilitate his ascents, while Petzoldt, a veteran of countless trips in the Tetons, had mastered the art of efficient movement as well as the importance of layering his clothing to keep him warm and dry. These talents were put to complementary use on K2, and would soon prove to be critical to the 10th as well.

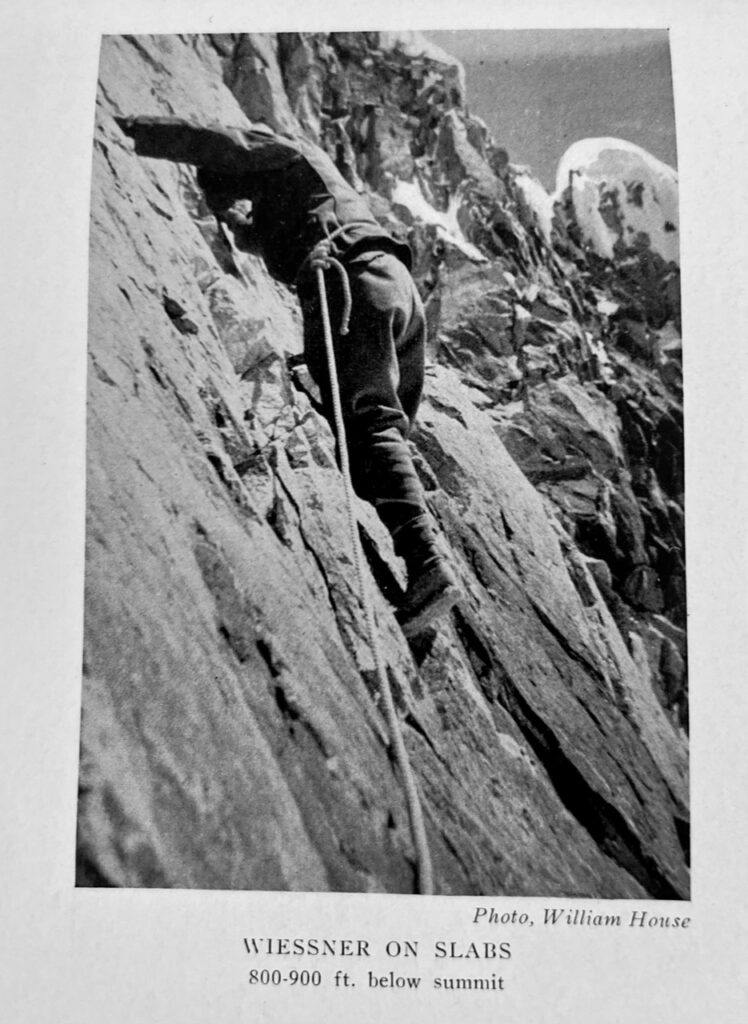

“By the 1930s,” as John Middendorf observed, “arguments against pitons in the high mountains had become moot, as the ability to fix, descend and later ascend a rope became intrinsic to strategy. But on the 1938 American K2 expedition, [Houston] did not consider pitons necessary.”

“Charlie was an Anglophile,” Petzoldt would later write, referencing the British aversion to the new-fangled equipment and techniques then coming into vogue. “He was so Anglophiled … that he forbade me to bring any pitons or carabiners on the trip. I used practically the last money I had to… buy me a bunch of pitons and carabiners [in Paris]. I had a chance to see pictures of [K2], and I wasn’t going up there without any pitons or carabiners. And come to find out, Bill House had done the same damn thing.” Petzoldt and House’s perspective would prove critical once the team’s early reconnaissances turned into a preposterously bold idea: to actually try to climb K2, via a route so difficult the Duke of Abruzzi and his guides “did not feel it even worth consideration” thirty years earlier.

“In order to effect the epic ascent of this Abruzzi buttress,” wrote Washburn, “seven camps were placed on ledges and snowdrifts even an alpine chough would have found it difficult to alight upon. Living for twenty-three days above 16,000 ft.,” he continued, “sleeping in …tiny tents secured in place by pitons and rickety foundations of loose rock, the four members of the climbing party succeeded in overcoming a series of climbing obstacles, many of which would be considered exceedingly difficult even at lower altitudes.”

House proved to be what Bates termed “a magnificent companion on the expedition. He solved the major problem on K2’s Abruzzi Ridge by leading a route up a break in a great reddish rock buttress.” The break, known forever after as the House Chimney, comprised a steep, flaring, relatively featureless 45-meter slot at 6700 meters that took House four hours to climb. He couldn’t have managed it without pitons, and his lead—deemed to be the finest climb done at high altitude before World War II—opened the way to the more moderate terrain above.

Though food shortages and the end of stable weather kept the group from reaching the actual summit, they attained a point nearly a mile higher than anyone had been on the mountain. The high altitude mark went to Petzoldt, who continued when Houston, exhausted, lay down in the snow to rest. At 8100 meters, Petzoldt’s final footprint was higher than any human had ever been.

Their attempt wouldn’t have been possible without European gear. In the article House wrote for the American Alpine Journal, he noted that the team’s “woolens”–the sweaters and underwear and turtlenecks–had been made in England. So had the mittens, socks, windproof suits, gauntlets, and boots. They’d used Primus stoves from Sweden and Eckenstein crampons from Italy and pitons made by France’s Pierre Allain and carabiners from Lawrie in London and ropes from the French company Beal, which had also made their snow shovels. Some of their tents had been purchased from Abercrombie in New York, as had their air mattresses, but on the whole, their kit had a decidedly European flair.

European influences impacted their attempt in more subtle ways as well. House, who had developed an appreciation for Weissner’s German-made pitons and carabiners, not to mention his Italian crampons and Austrian ice axes, had also absorbed his tactical approach to climbing. Similarly, Petzoldt had been influenced by Jack Durrance, a young climbing phenomenon he’d hired to help him guide in the Tetons. Durrance, in turn, had learned to climb in Germany, and his vision for bold new lines had been forged in the Munich school of climbing. On their 1936 ascent of India’s Nanda Devi, Houston and Ad Carter had climbed under the wings of the great British alpinists Noel Odell and Bill Tillman. On K2, all these influences came together to inform the team’s perspective on gear and clothing and tactics. Three years later, that same blended perspective would be put to use in service to their country.

Upon returning home, Bates resumed teaching, and supplemented his income with talks about K2. One such presentation, at Exeter Academy in February 1939, resulted in a job offer to teach at the institution. Another, at the Jenny Lake campground in the Tetons in the summer of 1939, led to his encounter with John McCown. A year later, Bates would nominate McCown for membership in the American Alpine Club, which of course would pave the way for McCown’s enlistment with the mountain troops, the ascent of Riva Ridge, the breaking of the Gothic Line and the end of the war in Europe.

Following his encounter with McCown, Bates traveled to Switzerland to join Carter on a climbing trip in the Alps. By now, Hitler’s increasing belligerence had begun to alarm the continent.

“At mountain huts,” Bates wrote, “it was not easy to get world news, but we did learn from hutkeepers that war was appearing more likely between Germany and Poland. The Germans were getting very aggressive and almost all the Swiss we met were apprehensive. We saw Swiss mountain troops maneuvering, and we talked about how the US Army could make good use of mountain troops too.”

When Germany announced that Poles had raped and murdered a number of German nurses and thrown their bodies into a river, Bates and Carter knew their trip was over. The German propaganda was the excuse Hitler needed to begin his war.

Carter rushed to visit a childhood friend. Bates scrambled to find a boat ride home. Miraculously, he secured the last berth on a ship sailing for New York.

“The boat was crowded,“ he wrote, “everybody with the story of what he had done when war was declared and rumors about submarine sinkings. At night the ship was fully lighted, the spotlight shining on a huge American flag painted on each side. … I wondered if the Germans were planning to change the map of the world as I had seen it changed … the year before.”

I’ve told you about K2, but I didn’t tell you about the boat ride at the start of the expedition.

Bates and a teammate had taken a German-crewed boat from New York to France. As they were wandering around the ship, they’d become disoriented, and had inadvertently stumbled into the crews’ quarters. On the wall was something that had chilled Bates’ blood: an official German map of the future world.

“All of Europe, except the USSR and the British Isles, was to be German,” Bates would later write, “…. Britain and Russia were shown cross hatched, meaning they were to become semi autonomous.”

Now, as Bates sailed away from Europe’s war, he remembered the unsettling sight of the meticulously detailed map of the world, redrawn in Hitler’s vision.

And that concludes Part 1 of our examination of the gear, clothing and food developed for the mountain troops–thank you for listening. In Part 2, we’ll follow Bates and friends as they head up the American Alpine Club’s efforts to assist the Army. We’ll also explore how those efforts converged with the Army’s mountain and winter warfare boards and the Office of the Quartermaster General to prepare the country’s mountain troops for war–and in so doing, established the foundation for outdoor recreation as we know it today.

Thanks as always to our new patrons, Aaron Pruzan, David McCormick, Doug Caldwell, Robbi Farrow, Larrie Rockwell, James Neu, Ruth Hoeren, Scott Kane, Scott Dorrance, and Susan Powers. These folks helped underwrite all the research that went into this episode. If you’re in a position to help support the show, please go to christianbeckwith.com, click the bring orange patreon button, and become an active part of our story.

Thanks to our sponsors, CiloGear and the 10th Mountain Whiskey and Spirits Company; our partners, The 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the American Alpine Club and the 10th Mountain Division Descendants; and our advisory board members, Lance Blythe, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt.

Until next time, thanks again for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.