In Part 2 of our deep dive into Camp Hale, we explore the rocky beginnings of the mountain troops’ high-altitude military encampment. Nestled in Colorado’s Pando Valley, the camp was more than a training base for what would become the 10th Mountain Division; it emerged as a social and military experiment that profoundly shaped the trajectory of outdoor recreation in America.

From the soldiers’ grueling acclimatization to the challenges of uniting skiers, mountaineers, and draftees under the harshest of conditions, Episode 12 uncovers the untold stories of struggle, frustration and resilience that emerged from the smog-filled valley.

We also rejoin John McCown as he embarks on his first journey to Camp Hale, witnessing the stark contrasts among the soldiers who would form the nucleus of this iconic unit. Through McCown’s eyes, we experience the Army’s struggles to adapt traditional flatland tactics to the demands of mountain warfare and the creation of protocols that would go on to revolutionize skiing, mountaineering, and wilderness travel after the war.

In This Episode:

- The Army’s ambitious yet chaotic vision for Camp Hale

- The psychological and physical challenges faced by recruits

- The cultural impact of bringing America’s best skiers and climbers together in one place

- The first steps toward institutionalizing mountaineering and outdoor skills within the military

- John McCown’s reflections on leading a diverse group of soldiers, from seasoned mountaineers to young draftees from the south who would comprise the heart of the unit

Special Thanks:

This episode is made possible by our partners:

- 10th Mountain Division Foundation

- Denver Public Library

- 10th Mountain Division Descendants

- 10th Mountain Alpine Club

And our sponsors:

- CiloGear – Use code rucksack for 5% off at cilogear.com

- Snake River Brewing – Bringing the spirit of the mountains to your glass

Support the Show:

Become a patron at christianbeckwith.com to access exclusive content and help keep this project alive. Special thanks to our newest patrons: Nelson F., Chris Johnson, Clay Kennedy, and more!

Join the Ninety-Pound Rucksack Challenge:

Celebrate the 80th anniversary of the 10th’s historic Riva Ridge ascent by participating in the 2025 Challenge on February 18th. Ski areas across the country are hosting events—find one near you or join independently. Details at christianbeckwith.com.

Merch Alert:

Show your support with official Ninety-Pound Rucksack caps, mugs, and t-shirts—available now on our website!

Advisory Board:

Thank you to Lance Blythe, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid, and Doug Schmidt for their invaluable expertise.

Episode 12: Camp Hale, Part 2

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and today we’re diving into the second part of our exploration of Camp Hale, the military encampment high in Colorado’s Pando Valley where the 10th Mountain Division’s unique mountaineering identity was forged. The impact of the base would go on to extend far beyond its military dimensions—but as we’ll discover, its beginnings would prove to be as rocky as the surrounding terrain.

For those who’ve been following along, you know this podcast is my way of mastering every facet of the Division’s evolution for a book I’m writing about the unit and its transformative role in outdoor recreation.

The story unfolds through the experiences of John Andrew McCown II, a young man from Philadelphia who, like so many of his peers, dropped everything after Pearl Harbor to join the Army. The podcast allows me to examine facets of the unit’s development while weaving together its various threads into a historically accurate portrayal of the details that shaped it. And as with all our episodes, I wouldn’t be able to do it without the support of our partners, the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the 10th Mountain Division Descendants, and the 10th Mountain Alpine Club, as well as that of our sponsors: CiloGear and Snake River Brewing.

Recently, I traveled to the Wyoming Ice Festival in Cody to give a talk on the 10th for the Parks County Search and Rescue Foundation. Both CiloGear and Snake River Brewing were well-represented—which felt fitting, given that Cody’s South Fork, home to one of the largest concentrations of waterfall ice climbing in the lower 48, is a wild, atmospheric place that demands the best of a climber and his or her gear.

Tucked into the Absaroka Mountains on the eastern edge of Yellowstone, the South Fork is remote. There’s no cell service, no city lights, just the sound of your own breathing as you make long, disorienting approaches through frozen creek drainages to towering amphitheaters and some of the most aesthetic ice lines you’ll find anywhere.

It’s a place that demands fitness, preparation and gear that works as hard as you do. That’s why I rely on CiloGear packs. Designed with intuitive features that strip away what you don’t need while giving you everything you do, they’re lightweight and indestructible, and they carry everything you need comfortably for hours on end. Their Worksack has been my go-to for years—it’s simple, durable, and built for the kind of adventures the South Fork has to offer. Right now, you can visit cilogear.com and use the code rucksack to get 5% off your purchase. Even better, CiloGear will match your purchase with a donation to the 10th Mountain Alpine Club, a collective dedicated to advancing alpinism in the spirit of the 10th.

And after a day of climbing the narrow ribbons and towering pillars of the South Fork, nothing hits the spot like an ice-cold beer from Snake River Brewing. They’ve been brewing award-winning craft beer in Jackson, Wyoming, since 1994, and they know how to get the spirit of the mountains into every pint. Whether you’re toasting your partner’s heroic lead with an Earned It Hazy IPA or savoring a full-flavored Pakos IPA while remembering that eerie sense you had of wolves watching from high above, Snake River Brewing brings the adventure straight to your glass. You can find their beers across Wyoming, Colorado, Idaho, and parts of Montana—or better yet, visit the Brew Pub in Jackson for killer brews, great food, and good vibes.

So here’s to CiloGear and Snake River Brewing—two brands that deliver, whether you’re climbing ice in Cody, celebrating the day’s adventure or getting fired up for your next day out.

Finally, a special thank-you to our patrons, whose support helps us keep this project alive. If you’re not yet a patron, consider joining our community to access exclusive content and help us continue telling this story. Go to christianbeckwith.com to learn more, or support the show by sharing episodes, leaving a review, or engaging with us on social media. Every bit helps.

And now, let’s catch up with John McCown as he prepares to join the mountain troops in Pando for the very first time.

[line break]

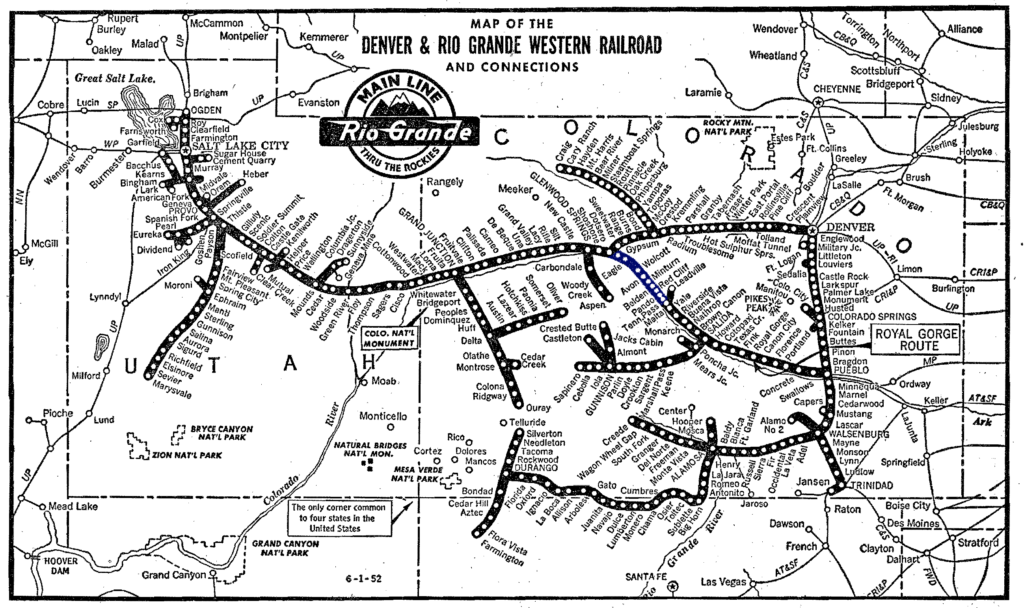

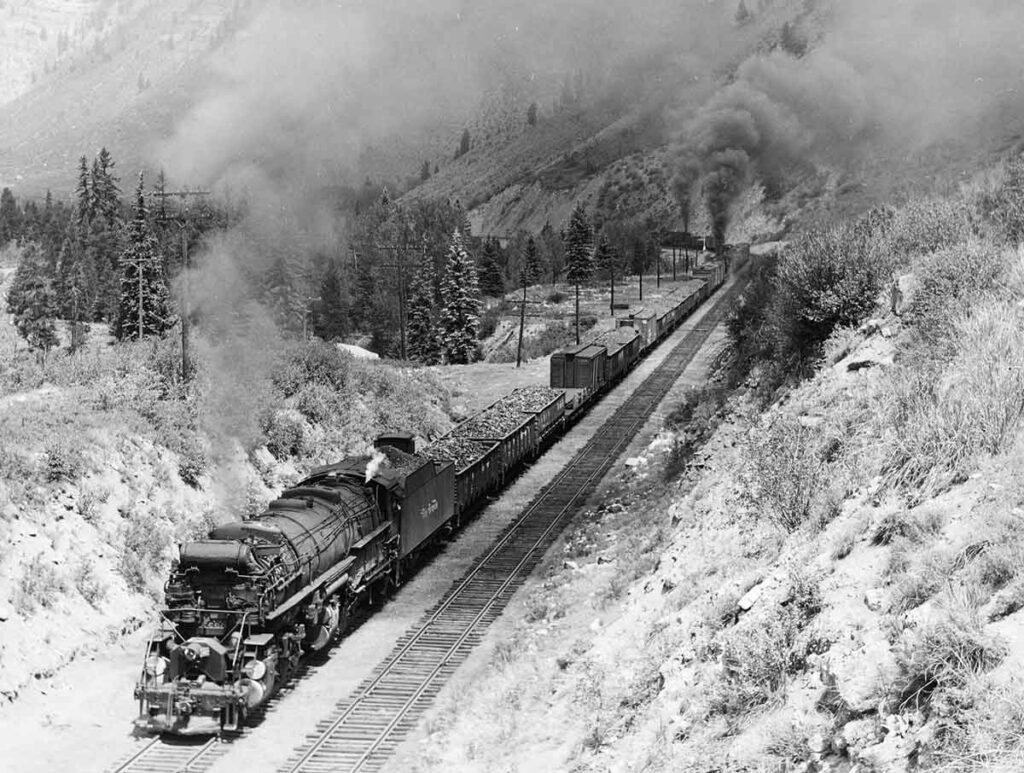

Three billowing columns of thick black coal smoke arced backward into the air as the Denver and Rio Grande train climbed steadily toward Tennessee Pass. Inside the long line of passenger compartments, soft winter light filtered through frosted windows, illuminating row after row of uniformed soldiers. They’d taken up every last mohair-covered bench seat, and their muted conversations blended with the train’s rhythmic clatter as the radiators hissed, battling the drafts for warmth.

John McCown rubbed the glass with the side of his fist. It was January 10, 1943, and, frigid temperatures aside, he couldn’t have asked for better weather for his maiden journey to Camp Hale. The day was dazzling—clear skies, white peaks carved against a dome of blue. Ever since they’d stopped in Leadville to add two engines for the final ascent over the Continental Divide, he’d been riveted by the landscape. To the east, long-shouldered ridges and 13,000-foot summits rose above evergreen forests, their crests blown clean by the wind. To the west, snowy peaks soared up from deep, shadowed basins, their ridgelines riven by steep couloirs. The mountains might have lacked the sharply angled buttresses and serrated aretes of the Tetons, but for the job ahead, they would do just fine.

A haphazard assortment of canvas duffels bulged from the luggage racks above the soldiers’ heads. John’s rucksack sat at his feet, his ice axe strapped to its side. Its hickory handle, shiny from use, had been with him from the Tetons to the Coast Range to the flanks of Mt. Rainier, and it felt mildly reassuring to have it here amid the woolen uniforms and darting eyes of the compartment. In Denver, he’d tried to ignore the soldiers’ stares as they’d flickered from the axe to the bright insignia on his freshly pressed jacket. He’d returned their salutes with a nod, his shoulders tightening under the weight of their glances.

The soldiers in the car were a mix of volunteers and enlisted men. It wasn’t hard to tell which was which. As the train continued to climb, the volunteers, college athletes recruited for their skiing expertise, jostled for views, ooh-ing and ah-ing with every new summit. The enlisted men were notably more subdued. Though they outnumbered the college boys four to one, they kept to themselves at the back of the car, their wool overcoats tightly buttoned and their garrison caps pulled over their ears for warmth. From what John could tell from their abbreviated exchanges, they were mostly from the south, they had not volunteered, and they were not excited by the landscape. Indeed, it seemed that more than a few of them had never seen snow.

Ahead of him, a boy peered out the window, half-standing and half-kneeling as he pressed his face to the glass. The sharp features of his face were dotted with acne; he didn’t look a day over 20. His left knee bounced up and down in the seat as he continued to watch the snow-covered forests that cradled the view.

“Bet you’ve never seen peaks like these back east,” one of the college boys said to no one in particular.

“We’re not in Kansas anymore,” whistled another. “These make the White Mountains look like foothills.”

“Think we’ll get camo outfits like the Finns?”

“What kind of skis do you think we’re getting?”

“I heard Northlands.”

“They’re giving Phil snowshoes. So he can carry our rifles.”

The boy with the acne flushed, his cheeks reddening, but he kept his gaze locked on the peaks.

“Phil grew up as a lumberjack . They’ll probably put him in charge of the mules.”

The boy turned slightly. “Careful what you joke about,” he said. “I’ll carry a mule, your skis, and your rifle and still be the first one down.”

Laughter rippled through the front of the car.

At 25, John was barely older than most of the soldiers, and under different circumstances, he might have joined in, but he held his tongue instead. He could still remember the banter on the troop train he’d taken to Ft. Lewis to join the 87th. He’d been a jangle of nerves all day, and the conversations in the compartment had felt as disjointed as his emotions. Hard to believe that had been less than eight months ago.

He turned to look behind him. Two rows back, a young man with a heavy face and a slightly crooked nose sat stiffly in his seat, shoulders slouched, staring straight ahead. His cap was pulled low over his eyebrows, and he’d tugged the lapels of his olive drab jacket tight against his neck. His cheeks were pale and blotchy. He looked miserable.

Steadying himself against the train’s movements, John pulled himself up, reached into the luggage rack, retrieved a woolen blanket, and made his way toward the back. Conversations hushed as soldiers straightened in their seats.

“Here,” he said, holding the blanket out to the boy. “No sense freezing before you’ve even stepped off the train.”

The boy looked up, surprised. His eyes jumped from the blanket to John’s insignia. When he reached out to accept the gift, John noticed his hands were rough and calloused. Farming, he guessed.

“Thank you,” the boy said, a southern cadence rolling off his lips, then added, “sir.”

John studied him for a moment. A small dusting of freckles graced his face. He couldn’t have been older than a teenager, and he looked like he’d spent far more time driving a plow than riding a train.

“What’s your name, private?” he asked.

“Rawlins, sir.” The boy paused. “Folks back home call me Buddy.”

“Where’s home?”

“Tennessee, sir. Sweetwater. In the Smokies.” Buddy paused again, glancing at the peaks outside the windows. “They’re not as big as these, sir.”

John smiled slightly, nodding. “You’ll do fine, private,” he said. “Just stay close to your squad. The mountains have a way of teaching you things you don’t expect.” He paused, then added, “A good way.”

“Yes, sir,” he mumbled, pulling the blanket around his wiry frame. He looked up. “I’ll try to remember that, sir.”

John returned to his seat, his mind lingering on the boy. If there were too many more recruits like Buddy, he’d have his work cut out for him

A shrill whistle pierced the air, followed by the shriek of boilers.

“There it is!” one of the college boys exclaimed, pointing to a ribbon of white in the middle of a forested mountain. “Cooper Hill!”

Soldiers crowded the right side of the compartment to see. John stood, too, his rangy shoulders filling the aisle as he peered over their heads. He could just pick out the faint tracings of a rope tow sparkling in the sun.

“There’s your home for the next few months,” he said with a grin. “Looks like we might have a few more trees to cut before we go skiing.”

One of the college boys hooted. Another clapped. John’s obvious delight seemed to shrink the space around him. It was infectious, and while it might have been unbefitting of an officer, it was perfectly understandable from the perspective of the mountaineer.

He felt a bump at his elbow. The boy with the acne—Phil— was standing at his side, eager for a better look. John towered over him by half a foot.

“You look like you’re good with an axe,” John said, stepping back so the boy could see.

Phil grinned, his cheeks coloring slightly. “Yes, sir,” he said. His features—oval face, pronounced cheekbones—seemed to brighten as he spoke. “We used to cut slopes on Balch Hill in summer so we could race. Good training, sir.”

“You a skier?” John asked.

“Yes, sir,” Phil replied. His eyes lit up. “Dartmouth. ’44.”

“You don’t say,” John’s interest was piqued. “You know Walter Prager?”

Phil’s smile widened. “Yes, sir. He’s my coach.”

John chuckled. “Well, he must have known you were coming. He’s waiting for you at Camp Hale.”

Phil’s shoulders straightened at that. He looked up at John, then looked back out the window, grinning. His excitement made John feel a little lighter. A kid who raced ski slopes he’d carved on his own—that was exactly the kind of man he’d need at Pando.

Cooper Hill disappeared behind a bend in the tracks. A moment later, the car plunged into darkness as they entered a tunnel. A single overhead light shone dimly above.

With nothing left to see, John made his way back to his seat. He had a lot to think about.

With nothing left to see, John made his way back to his seat. He had a lot to think about. In the five months since he’d left Ft. Lewis for Officer Candidate School, friends from the 87th had kept him abreast of the unit’s developments. They’d been unfolding with breathtaking speed.

Lieutenant Johnny Woodward, the University of Washington ski phenomenon whom John had met at Ft. Lewis the previous spring, had written to tell him of Colonel Rolfe’s ongoing efforts to wrangle a mountain unit out of the War Department’s vague directives. In August, Rolfe had been assigned to Colorado’s Camp Carson to activate the Mountain Training Center, the vanguard of the Army’s efforts to expand the 87th into a full-blown mountain division.

Woodward had joined Rolfe shortly thereafter. One of the mountain troops’ most experienced men, he’d led the Army’s experimental ski patrols the winter before the 87th’s activation, then coordinated its ski training on Mt. Rainier. At Camp Carson, he’d been tasked with forming a training detachment for the MTC. He’d handpicked a hundred of the 87th’s top skiers and mountaineers for the cadre. John was one of them.

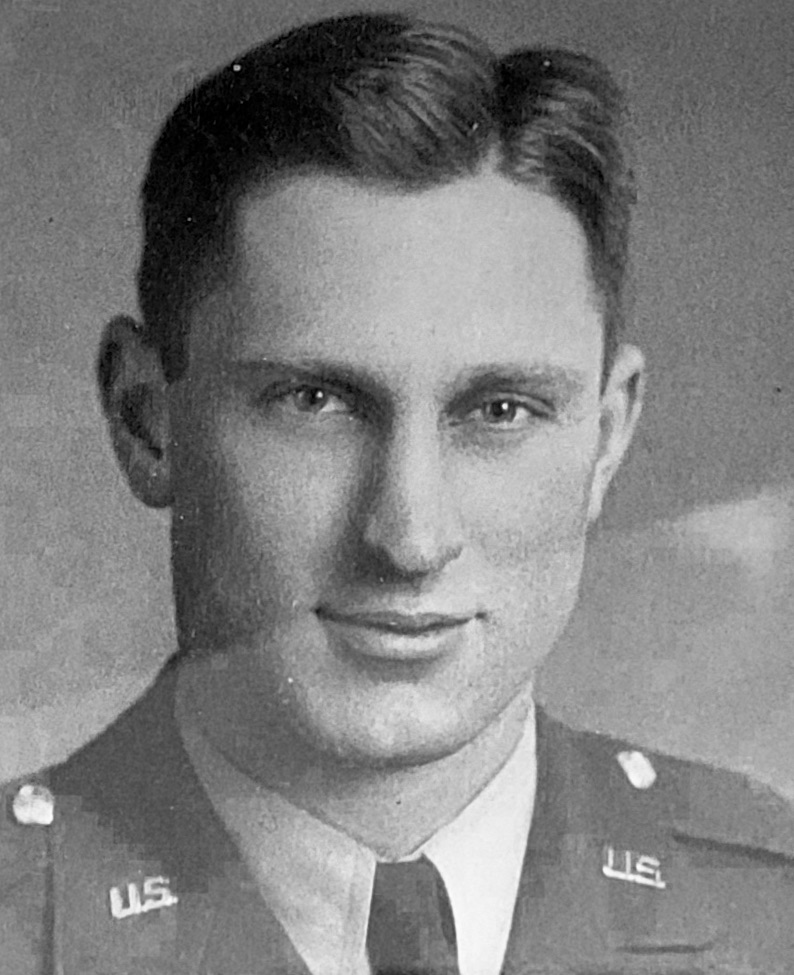

Rolfe graduated from West Point shortly before U.S. involvement in World War I. He served in combat with the 7th Infantry Regiment, and received the Distinguished Service Cross for heroism and the Purple Heart for wounds suffered in a gas attack.

Between World Wars I and II, Rolfe carried out a variety of assignments with increasing rank and responsibility, including professor of military science at Rutgers University, and senior observer and advisor for the Wisconsin National Guard. He also graduated from the Command and General Staff College and the Field Artillery Officer Course, after which he served as senior Infantry instructor at the Fort Sill Field Artillery School.

During World War II, Rolfe specialized in winter operations and mountain warfare. In 1941 he was assigned to command the 1st Battalion, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment. His success at organizing this battalion and leading it during its initial training led to assignment as commander of the regiment and promotion to colonel. Unknown Army planners apparently thought assigning Rolfe to command a unit that would train to use skis and snowshoes was logical, because he had been born in New Hampshire; they were apparently unaware that he had left the state at six years old and had virtually no experience in winter sports. Despite his unfamiliarity with skiing and snowshoeing, Rolfe soon became proficient, and ensured that the soldiers in his regiment did likewise.

From 1942-1945, Rolfe commanded the Camp Hale, Colorado, Mountain Training Center, and received promotion to brigadier general. During his command of Camp Hale, the 85th, 86th, and 87th Mountain Infantry Regiments were organized as the 10th Light Division (Alpine), and Rolfe was responsible for ensuring that the division had the facilities and equipment necessary to complete its training, to include ski slopes, cliffs for rappelling, skis, and winter camouflage uniforms.

Near the end of World War II, Rolfe went to France as deputy commander of the 71st Infantry Division, and took part in the Rhineland campaign and the Western Allied invasion of Germany.

By the time Rolfe had moved the MTC to Camp Hale in November, he’d been working to fulfill the War Department’s mandate for a full year. Thanks to his leadership and the assistance of experts like Woodward, the framework for a mountain division was now in place—but the majority of the details surrounding its development had yet to come into focus. Which is where John came in.

Rolfe had sent promising young men like John to OCS to help build out the unit, but OCS had been designed around warm weather and flatland tactics. At Ft. Benning, John had spent hours with Charlie McLane and Worth McLure debating how to adapt the Army’s standard infantry tactics to the realities of mountain warfare—but all they’d come up with were theories. Camp Hale would put their ideas to the test—and Rolfe, who had recently been promoted to Brigadier General, was counting on them to succeed.

And they had to figure it out fast, because Pando was already filling up. As chaotic as the expansion at Ft. Lewis had been, Camp Hale, Woodward had assured him, represented an entirely new level of bedlam.

As a newly minted second lieutenant, John would be expected to bring order to the mix. The responsibility didn’t faze him, but his new rank gave him pause. A number of the men who would soon be under his command had more mountain experience than he did.

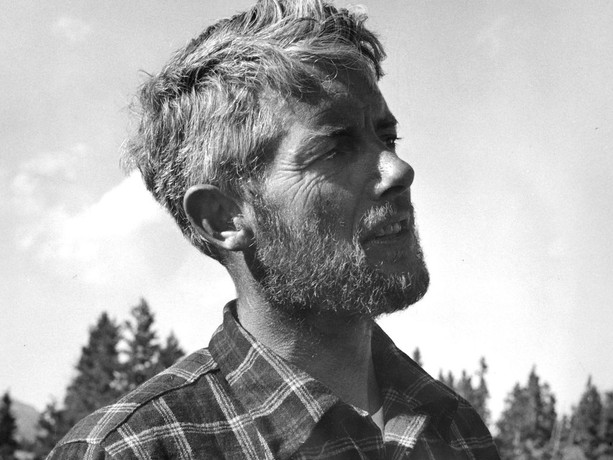

David Brower, the pioneering Sierra Club climber whose Manual of Ski Mountaineering had served as one of the 87th’s handbooks, had joined Woodward at Camp Carson, where they’d worked to put together the mountain troop’s first field manual. He was now at Camp Hale, as was Joe Stettner, the German-born alpinist who’d emigrated to America to escape the rise of Hitler and the Third Reich. Joe had established some of the hardest routes the country had ever seen alongside his brother Paul. Compared to men like these, John’s climbing experience seemed downright pedestrian. He wondered how they’d reconcile their differences in rank—and use it to teach recruits like Buddy, who’d be starting their mountain tutelage from zero.

John was particularly intrigued by the news that an eighteen-year-old prodigy from Seattle had joined the unit. Earlier that summer, Fred Beckey had made the second ascent of Canada’s Mt. Waddington with his sixteen-year-old brother, Helmy. The climb had stunned the mountaineering community. Mt. Waddington was considered one of North America’s hardest peaks; its first ascent had been achieved only five years earlier by Fritz Wiessner and Bill House, two of the country’s top alpinists. John himself had attempted the mountain with his partner Ed McNeill in 1941, barely escaping with his life. John couldn’t wait to trade notes—but with fraternizing between the ranks prohibited, how to do so remained an enigma.

As John tried to piece together everything he’d learned at OCS, everything he’d heard about Camp Hale and the variables of his new assignment, a change in the acoustics announced the tunnel’s end. A moment later they burst into sunlight, and soldiers scrambled to get a glimpse of the Pando Valley—but their excitement quickly gave way to confusion.

John was confused too. He’d expected to see Camp Hale laid out with military precision on the valley floor. Instead, the rolling foothills on either side ended in cloud. As the train plunged into the blanket, the compartment filled with an unmistakable smell.

“Smoke,” one of the college boys said with surprise.

John rubbed at the glass and frowned. “Inversion layer,” he said quietly. The cloud wasn’t a cloud. It was smog.

The train’s brakes shrieked. Row after row of barracks began to emerge from the haze. As the train came slowly to a halt, soldiers wrestled their duffels from the overhead racks. John shifted his long legs, rose, plucked his pack from the floor, and set it on his seat beside him to wait.

Ahead, Phil struggled with his duffel, the weight of it threatening to pull him back into his seat. John moved forward with a quick stride, grabbing the bag and swinging it easily off the rack. He steadied it as Phil looped the strap over his shoulder.

“Thank you, sir,” Phil said, his voice brimming with excitement as he looked up at John. “I’m looking forward to this, sir.”

John nodded, clapping him lightly on the shoulder before stepping back to let the others pass. As soldiers continued spilling into the aisles, Buddy shuffled forward, his duffel lashed to his back.

John waited for him to approach. The younger man’s cheekbones were clenched with nervous tension.

“What unit did you say you were with, private?” John asked.

“33rd Division, sir. Camp Forrest, Tennessee.”

John nodded. He leaned closer. “You’ll do fine, Buddy,” he whispered. “Just don’t eat the yellow snow.

Buddy looked momentarily confused. “Yes, sir,” he said. When John winked, a small smile crept over his freckled face.

John shouldered his pack. The acrid smell of coal smoke drifted through the car. At Ft. Benning, he’d read the directives, memorized the training schedules, and studied the logistics of the Army’s plans. He and Charlie and Worth had led their fellow candidates through simulated battles and pored over the field skirmishes outlined in their books. They’d deliberated their Camp Hale assignment and how they’d carry it out until the details had seemed clear as day. Now, though, as he thought about Phil and Buddy, he realized the reality of what lay before them all was as murky as the haze outside his window.

The brief exchanges lingered in his mind. The mountains had taught him about resilience, commitment, and the importance of his teammates. Now, he’d have to teach the same to these boys. He didn’t know how he’d navigate the task ahead—but as he shifted the familiar weight of his pack onto his shoulders, a climber’s resolve settled over him. With their help, he’d figure out a way.

[Opening narration from Warner Brother’s 1943 film, The Mountain Fighters]

How do we talk about Camp Hale, now that we’ve arrived, at long last, at its start? Contrary to popular belief, the 10th Mountain Division proper never even trained in Colorado; it wouldn’t be activated until November 6, 1944, nearly six months after John and his comrades had departed Camp Hale for flatland training in Texas. The various regiments and field artilleries and medical battalions and ordinance companies and military police platoons that General Rolfe had begun assembling in the Pando Valley were part of the 10th’s foundational elements, to be sure, but on the day John rode the coal- train into Pando, the unit remained a test force, its future still very much in doubt.

Should we cloak its skeletal outline in robes of hagiography, v à la Warner Brothers’ 1943 production, The Mountain Fighters, glossing over its troubles as the national media of the day was apt to do? Or do we dive head-first into those troubles: the noxious pollution, the debilitating altitude, the psyche-sucking cold, the specter of ambivalence that hung like a shadow over the entire make-it-up-on-the-fly endeavor?

What’s important for me to emphasize, and for you to know? In the wake of Pearl Harbor, the country had united in an existential effort to defeat Hitler and the Axis powers. Teenage boys and men in their twenties had poured into bases around America to fight on behalf of their country. While their childhood friends shipped out to the European and Pacific Theaters, the mountain troops remained stateside, training in all seasons and all types of weather, learning to climb and ski and camp and hike on maneuvers that lasted for days or weeks or even months at a time, their morale oscillating with each new rumor about their own deployment.

Should we focus on the story’s military angle—Rolfe’s struggles to build a mountain unit on the scaffolding of the Army’s flatland tactics and protocols, the draft-induced tension between the old Army regulars and the new civilian recruits, the disparity between the mountaineering talent of volunteers like David Brower, Fred Beckey and Joe Stettner and that of commanding officers who had never swung an axe or held an edge?

Or should we examine the story behind the story: What happens to young men when they are thrust into circumstances beyond their control, deprived of ordinary social outlets in general and the company of women in particular, and forced to train indefinitely without an endgame in sight? The recruits pouring into Pando were at the height of their testosterone-fueled abilities to fight. They were also civilians, at the height of their biological imperative to reproduce, and, walled off from the outside world, they existed in a state of pronounced social isolation. What sort of psychological impact did the segregation have on them, and how would it affect their outlook once they were re-inserted into civilian society, bent and battered by war?

Never before had the country’s best skiers, climbers and mountaineers been gathered in the same place at the same time to resolve a riddle of the magnitude General Rolfe had been tasked with addressing. They would do more than develop protocols and doctrine where none had existed; they’d create a distinctly American form of institutional knowledge that transformed skiing, mountaineering, mountain rescue, avalanche science, and wilderness travel after the war.

Before Pearl Harbor, climbing and skiing had been the province of the elite. At Camp Hale, men like John McCown turned their niche expertise into a teachable military discipline, instructing tens of thousands of soldiers to operate in cold weather and mountainous terrain under the pressures of war. Operating out of the Office of the Quartermaster General, mountaineers like Bob Bates, Bestor Robinson and Bill House would collaborate with American manufacturers to equip these troops with the best gear, clothing and food the country had ever produced.

But Camp Hale was more than a base. It was a hub. Men like McCown who were headquartered in the Pando Valley would be sent out on special missions, instructing thousands of GIs from other divisions in the art of outdoor self-sufficiency—and those men, in turn, would teach their own units the same skills, disseminating outdoor expertise across the Army and eventually the country. When the specialized equipment became Army surplus, soldiers who had learned to ski and climb and camp with it would buy it for pennies on the dollar and teach their families as well. The results democratized the outdoors, opening it to broad swathes of the American public for the first time and helping lay the foundations of today’s $1T/year outdoor recreation industry in the process.

So: Do we focus solely on the troops’ training at Camp Hale, or do we trace its ripple effect to the postwar embrace of the outdoors?

Camp Hale changed everything. It wasn’t just a military experiment. It was an unprecedented social experiment as well: an instant mountain town built at 9,200 feet in seven months’ time to train tens of thousands of soldiers to fight amidst the most challenging conditions the Army could find. As with all great experiments, it yielded unintended consequences that were at least as consequential as its primary goals.

[Line break]

All of these threads are connected to our narrative, and they all came together at Camp Hale. So where, and how, do we begin?

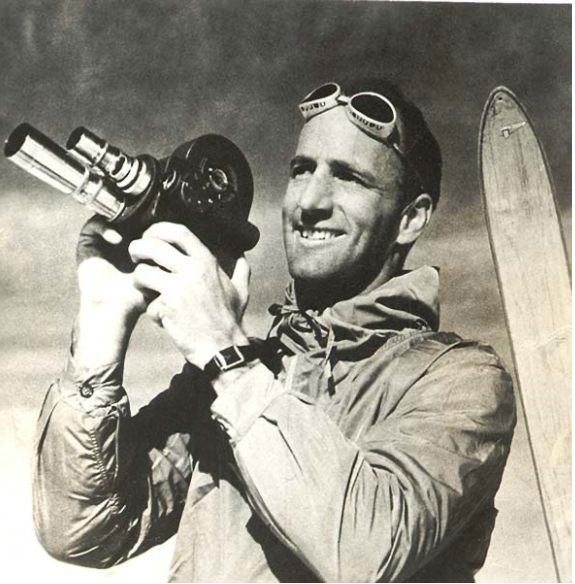

In developing this podcast, I rely on a combination of sources for my research, and they run the gamut from the objectively reliable to the subjectively inconsistent. Let’s start today’s episode with one of the former: John Jay’s History of the Mountain Training Center, a military-sanctioned report written contemporaneously by someone who was there and cross-checked by the Army’s own historians.

During his undergraduate winters, Jay filmed numerous local events, including the Williams Winter Carnival, the Dartmouth Winter Carnival, the second Inferno Race down the Headwall of Tuckerman’s Ravine, and the Madison Square Garden’s Winter Sports Show. Time, Inc. hired Jay to write commentary for the prestigious March of Time.

He released his first short film, Sons of Eph, in 1937, and graduated from Williams the following year. In the late 1930s, he was commissioned by Williams College, the Canadian Pacific Railway, and Panagra airline to produce promotional films. He was selected for a Rhodes Scholarship in 1939 but the war intervened.

In 1940, he released his first feature film, Ski the Americas, North and South, which played to more than 50,000 viewers during its tour. The following year, he released two more films, South for Snow and Ski Here, Señor. He was also drafted into the Army. Assigned to the Signal Corps, he traveled to Sun Valley to make the training film, The Basic Principles of Skiing, which would be used to train mountain troops throughout the war.

In January 1942 he was assigned to the Mountain and Winter Warfare Board at Ft. Lewis as Photographer and Meteorologist. His responsibilities would expand to include public relations, and in the spring of 1942 he returned to Sun Valley to make ten additional training films for the mountain troops. He also released They Climb to Conquer, and the following year released Ski Patrol, which the Army used to help with its recruitment efforts.

Throughout the war, Jay continued to make training and recruiting films and evaluated equipment for winter warfare. In late 1943 he was promoted to Major and named Commanding Officer of the 10th Mountain Division’s Reconnaissance Troops. In 1944, he wrote the definitive History of the Mountain Training Center, which was released in 1948.

Following the war, he embarked on his defining accomplishment as the father of modern ski cinematography, releasing nearly a film every year for the next thirty years.

As Jay points out, the long list of uncertainties plaguing America’s first mountain unit didn’t include the Army. It had been ambivalent when it gave Rolfe his marching orders at Ft. Lewis, and it remained ambivalent when it directed him to relocate the operation to Colorado.

“All … Colonel Rolfe knew when he was called to Camp Carson in August 1942,” Jay wrote, “was that a ‘test force’ of specially trained mountain soldiers was to be established at Pando that winter, with his former regiment, the 87th Mountain Infantry, as the nucleus.” The Army wanted Rolfe to expand the test force into a full mountain division in the spring, but as he took up residence on the eastern fringes of the Rockies, the actual point of the entire experiment remained maddeningly vague.

To be fair, the move to Colorado did include a rebranding. Gone was The 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment, a mouthful if ever there was one. In its place, the endeavor was to be known as the Mountain Training Center. But Rolfe’s new orders, which were to “develop procedures and manuals, test equipment, and conduct training in mountain warfare,” sounded a lot like his old ones. He had the unit’s experiences at Ft. Lewis and on Rainier to go by, as well as the input of experts like Woodward, but without additional clarity from above he was still flying by the seat of his pants.

Jay tried to provide the Army with cover for its equivocation. The two directives, he noted, were “phrased in these general terms undoubtedly because of the newness of the venture, and the fact that at that time the War Department had no concept of where or when these new troops might be called upon to operate….” But there was no explaining away the resulting uncertainty, or the effect it had on morale.

“The mission throughout [remained] indefinite,” Rolfe said. “We never knew whether we were training small units to go overseas … or whether we were developing a large tactical unit which would go across as a whole.”

The 87th had been a “Break glass in the case of emergency” contingency plan in the event cold-weather expertise, God forbid, was ever needed. Now that the operation was in Colorado, it had a new name, but it was still the Army’s misbegotten child, and as such remained subject to general disregard from above. As Jay noted, War Department officials “never took much stock in what the 87th was supposed to do.” As a result, a communication abyss existed between Washington DC and Washington State.

The move to Colorado did little to change the situation. “Throughout the growth of the mountain troops,” Jay wrote, “there was all too ample evidence of the lack of proper liaison between the men who were doing the planning and those who were … actually carrying out the work.” Had Rolfe managed to corner a War Department official in the shadowed recesses of a Colorado speak-easy and pleaded for additional clarification, the answer might well have remained, “Figure the damn thing out, and get back to us when you do.”

“We don’t know whether we’ll be sent to Norway, Russia, Burma, or the Italian Alps,” Rolfe muttered, “and each area presents different problems that demand ultra-specialized training. It is physically impossible with the time and facilities on hand to train men for combat in all these areas.”

And yet there he was, preparing the Mountain Training Center for a range of possibilities while staring into the crystal ball of the war’s future.

[line break]

Camp Carson is located at 6,000 feet near the southern end of the Front Range mountains. Rolfe’s orders had been to prepare the MTC to move to Pando the moment the last carpenter moved out. “For six weeks,” Jay wrote, Rolfe “drilled and trained his new command with but one aim in mind: to get them acclimated to higher altitudes.” Every day, officers and privates alike ran a fast mile “to strengthen their lungs for the thinner air … at Pando,” as Jay put it, “where carpenters were already demanding double wages because of the effects of altitude on their systems.” Muleskinners led their mules into the canyons adjacent to camp wearing heavy rucksacks. At night, enlisted men, noncoms and officers “crowded the lecture halls to hear talks and see demonstrations on mountaineering, camping in snow, and on life in general in the high mountains. Calisthenics … gave way to ski exercises specially designed to build up muscles used in skiing and mountain climbing.”

And on November 16, 1942—a year and a day after Rolfe began assembling the test force at Ft. Lewis—Pando was more or less ready, and so were its future occupants. As Rolfe watched, all 32 officers and 2,100 men of the Mountain Training Center left Camp Carson in a convoy of trains, trucks and private cars and proceeded across the Continental Divide to Camp Hale, 158 miles away.

Jay’s history provides a broader context for their arrival.

“Survivors of the original Mountain Training Center will long remember that first winter at Camp Hale,” he wrote. “All the many problems connected with moving into a nearly completed post were multiplied tenfold by climate and location. A light snow had fallen previous to the troops’ arrival, hiding the trash, debris, and mud of a summer’s work, but it turned the streets into a quagmire of slush, which concealed the nails that soon began to puncture G.I. tires. No theaters were completed nor clubs for men or officers; there was no entertainment on the post whatsoever, and furthermore there was none off it, as Leadville was immediately placed off limits for military personnel by Colonel Rolfe. Week ends were restricted to twice a month, because of the transportation problem; at other times no one was allowed to leave the post for any but emergency reasons. The camp had no facilities for laundry and cleaning, no gasoline, restaurants, or even a guest house for officers’ ladies. The much-talked-of housing project for noncommissioned officers’ families, so strongly recommended by one of the [Army’s advisory] boards, failed to materialize; the nearest sanctioned place was Glenwood Springs, seventy-two miles away, and the commissioned officers’ families soon filled that up. Camp Hale became known as ‘Camp Hell’ during the first grim weeks of occupation.”

Hal Burton, a newspaper reporter who joined the unit at Ft. Lewis and served alongside McCown all the way to Italy, wrote his version of events in a book entitled The Ski Troops. Published by Simon and Schuster nearly twenty-five years after the fact, it recounted the unit’s developments in the third person, with a journalistic objectivity that was nonetheless informed by Burton’s own experiences.

Like Jay, Burton had “been there,” nearly from the start, and thus had a front-row seat to the proceedings. Unlike Jay, his account was not cross-checked by military historians—but given that he pulled much of it from Jay’s work, sometimes nearly verbatim, it stands as a fairly reliable source of information.

When the U.S. entered World War II, Burton enlisted early, becoming one of the first to join the Army’s experimental mountain unit. Assigned to the Canadian Rockies to work on military operations in the high mountains, he and his detachment camped on the Saskatchewan Glacier north of Lake Louise, testing military snowmobiles (Weasels) under alpine conditions. He also trained artillery officers at Camp Carson, Colorado, developing the Cheyenne Canyon climbing area, still used by the military today to train National Guard and Reserve units in rock climbing. Burton also convinced military leaders to take his climbing school to the Crestone Needles, where soldiers trained on some of the finest climbing routes in the Rockies.

In 1943, Burton helped lead a climbing school at Seneca Rocks, West Virginia, where units from twelve other divisions were trained by 10th Mountain Division instructors. Burton devised a harrowing training scenario where assault teams scaled a 300-foot cliff under simulated artillery fire, with instructors throwing fuse-lit dynamite to simulate combat. The experience was so intense that many soldiers later remarked that actual combat was anticlimactic in comparison. Toward the end of 1943, Burton and fellow instructor Ed Link led a team to Italy, where they trained British and Gurkha forces, known for their climbing prowess.

Burton’s 10th Mountain Division unit participated in the famous Italian campaign, including the daring raids on Riva Ridge and Mount Belvedere. The assault on Riva Ridge, requiring a 1,500-foot vertical ascent, succeeded because the Germans believed no force could scale it.

“Camp Hale,” Burton observed, “was almost an unmitigated disaster. It had never occurred to the Pentagon that this isolated camp, in a barren pocket among the high Colorado hills, was at too high an altitude….”

As we detailed in our last episode, this was not entirely true, as the workers who dropped like flies during its construction had quickly found themselves in violent agreement with the engineers who’d cited the altitude as one of the primary causes for their concern. At 9,200 feet, Camp Hale sat higher than most Alpine passes, which typically range from 6,000 to 8,000 feet. Burton underscored the comparison: “The altitude of Hale was about the same as the Hörnli Hut, where the final ascent of the Matterhorn takes place.” He could make the connection firsthand, having reportedly climbed the mountain in the 1950s.

Climbers like mountains. Mountains are high. The higher one climbs, the lower the air pressure, and the lower the amounts of oxygen available to one’s body. Without enough oxygen, physical exertions can result in headaches, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, fatigue, trouble sleeping, dizziness, lightheadedness and changes in one’s vision.

The process of adjusting one’s body to lower oxygen levels is called acclimatization, and it takes time: up to three weeks for 6,000 feet and four weeks for 9,000. Yet the Army’s approach to acclimatization at Camp Hale was essentially non-existent.

In mountaineering circles, there are various schools of thought regarding the best way to acclimatize. Westerners often subscribe to an iterative “climb high, sleep low” approach, wherein one adjusts to altitude over a series of ever-higher forays interspersed with sleep at lower altitudes. Masters as they were of the art of suffering, Soviet-era climbers employed a “climb high, sleep high” approach: they would simply climb to altitude, crawl into their tents and endure the lethargy and headaches that ensued.

There is no school of thought that sanctions the approach I once took as part of an expedition to Kyrgyzstan. From the capital city of Bishkek, elevation 2,600 feet, we traveled by military truck to a base camp at 10,000 feet in the unexplored Kokshall-Tau range on the border with China. By the time our truck departed Bishkek, I’d spent a week climbing up to 15,000 feet in the mountains outside the city, so I experienced minimal effects. The same could not be said for one of our British teammates, who’d hopped on the truck after flying in from England. After three days’ travel, including a day spent extricating our truck from axle-deep mud with our ice axes, we reached base camp. Enthusiastic young man that I then was, I immediately set out with a teammate to investigate the potential of the 20,000-foot peaks on the horizon. Upon our return we found our British teammate missing. He’d been evacuated by helicopter. The near-instant insertion at altitude had yielded a life-threatening case of high altitude pulmonary edema, or fluid in the lungs.

Ours was not a wise strategy. It was, however, the one adopted by the Army at Camp Hale. As new recruits accustomed to sea level arrived by train, they were unceremoniously dumped at the Pando depot, gasping for breath. “Newly arrived recruits were forced to unload heavy crates from boxcars,” Jay wrote, “to shovel a couple of tons of coal, a day or so after their arrival at the nearly two-mile-high camp.” Six months after the camp opened, battalions were still being sent out directly on three-week bivouacs. “Many of the men had been bank clerks and white-collar workers in New York City the week before,” Jay noted. At least three of them ended up in the hospital before receiving medical discharges.

Unfortunately for the new recruits, altitude was hardly the only problem they encountered at Camp Hale. There was also the matter of that inversion layer. The locomotives’ coal-powered steam engines and the more than 500 coal-powered stoves used to heat the camp barracks filled the valley with a perpetual haze that hung over Camp Hale like a plague.

“Seen from above, on the road up to Cooper Hill,” Bill Putnam wrote in his memoir, Green Cognac: The Education of a Mountain Fighter, “the valley of Camp Hale often looked like a lake, only the surface was not water, but rather the top layer of the smog, below and in which we lived.”

I knew Bill. When I took over the editorial duties of the American Alpine Journal in 1996, he was one of the Club’s emeritus members, an Honorary President who had appointed himself its de facto historian. His strong sense of self, coupled with his privileged lineage—he came from two of New England’s most illustrious families—might have been off-putting to some, but he was always good for a story, and he didn’t let the facts get in the way of telling it.

At 18, he left Harvard to join the newly formed mountain troops, training in Colorado before deploying to the Aleutians with the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment. He participated in the harrowing 1943 assault on Kiska, a Japanese-held island in the Aleutians, and later fought with the 10th Mountain Division in Italy’s Apennine Mountains. As a platoon leader, he was wounded twice in combat, earning two Purple Hearts, a Silver Star, and a Bronze Star for gallantry. His wartime experiences formed the basis for Green Cognac, his memoir detailing the 10th Mountain Division’s brutal campaigns.

After the war, Putnam returned to Harvard and pursued a career in broadcasting, founding WWLP, Springfield’s first television station, in 1953. He expanded into multiple markets and was later inducted into the Broadcasting Hall of Fame.

An accomplished alpinist, he made numerous first ascents in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia, edited influential climbing guidebooks, and played a leading role in the American Alpine Club and the UIAA. In 1987, he became the sole trustee of Lowell Observatory, guiding its expansion and the construction of the Lowell Discovery Telescope.

Bill’s memoir falls squarely in the category of subjectively inconsistent. Still, like Jay and Burton, he had been there, and he’d spent more than enough time living in the soup to report accurately on its choking, ever-present qualities.

In a letter Burton excerpted in his book, a California recruit elaborated on the air quality. “This morning,” the soldier wrote on January 26, 1943, “I could just make out the outline of the eighth barracks building 50 feet away… every breath I took just reeked of … smoke…. Last night, [it] was so thick in the barracks itself that you could plainly see it by looking at the light at the end of the room…. [T]he perpetual smoke cloud, train smoke, and all the soft coal smoke from all the buildings here … hangs like a pall over the camp, night and day….”

Burton summed it up succinctly: “The clean, white snow of skiing song and story was there, all right, but it was high above the camp.”

Adding to the rigors was the humidity, or lack thereof. As Lou Dawson pointed out in our last episode, the Pando Valley exists in a high, semi-desert climate, which, when combined with the elevation, created desiccated conditions for the camp’s new residents.

“Both the air pressure … and the 20% relative humidity were abnormally low for most of us,” Putnam wrote. “In an attempt to increase atmospheric humidity within the barracks, local regulations at Camp Hale called for a few buckets of water to be poured on the floors at night, just prior to bed check.” When temperatures dropped below freezing, the floors turned to sheets of ice.

The cumulative effect of the smoke, the humidity and the altitude led to a respiratory scourge so acute, it got its own name: the Pando Hack. The affliction “shook the whole frame and left the [victim] weak and water-eyed,” Jay wrote. Its symptoms—which included a “nasty sore throat” and a dry, grating, throat-clearing wheeze — soon “had the medical staff,” as Jay observed, “working overtime.”

Sick call is common in the Army. So is its systematic abuse. “More soldiers go on sick call than civilians on buses,” observed an article in the Camp Hale newspaper. “There was a fellow … who bragged that he had never been on sick call. When the doctors heard about it they rushed him straight to the hospital, and he turned out to be the only genuine case that had come along since the Selective Service Act was put into effect.”

The article in question was a syndicated piece first published in Yank, the Army’s weekly magazine. It was written by Sgt. Allen Kleinwaks. Sergeant Kleinwaks was not stationed at Camp Hale. Had he been, he would have likely revised parts of his essay.

Sick call, Kleinwaks wrote, most generally afflicted “soldiers who have kitchen patrol one day and a date in town the next.” While kitchen patrol, or KP, was as common at Camp Hale as it was everywhere else in the Army, the same could not be said for dates.

As we discussed in our last episode, the closest town to Camp Hale was Leadville, a mere 18 miles away up and over Tennessee Pass. But Leadville had a prostitution problem, a gambling problem, and a drinking problem, and despite the fed’s efforts to persuade the town to clean up its act, the brothels and gambling dens and saloons had continued to do brisk business during Camp Hale’s construction. Once the camp opened its doors, an outbreak of venereal disease jostled with the Pando Hack for the medical staff’s attention. General Rolfe couldn’t do anything about altitude or smog, but he could do something about sexually transmitted diseases, which is why he’d placed Leadville off-limits to the troops.

Prostitution aside, the tete-a-tete between the sexes is key to a young person’s social and emotional development—and for the teenage boys and young men who began to occupy Camp Hale, it was essentially absent. By December 1942, fewer than 200 of the encampment’s 6,000 residents were women. Apart from Leadville, the closest towns were Redcliff, Minturn, Eagle and Glenwood Springs—but they were hamlets. Denver and Colorado Springs were both 150 miles away. Private cars were a rarity on the base, which left trains, but even a train ride to Glenwood Springs took four hours one way. Denver was nine hours. For a soldier with a weekend pass, neither was viable, which meant staying in Pando, which essentially meant forced celibacy.

The Army tried to compensate. Plans for the base included an 1,800-volume library, an adjacent writing room and a music room complete with a radio phonograph, a growing record collection and a referee to decide who got to play what. Three theaters equipped with the finest projectors and sound apparatus available would soon offer a lineup of current films. Efforts were underway to bring in popular entertainers, and the field house, once constructed, would offer everything from boxing and wrestling matches to fencing, tennis, badminton, basketball, softball and baseball.

But that was all to come. For now, traveling radio and stage shows, fearful of the high altitude, shunned Camp Hale. No one could leave the post during weekday evenings, leaving officers and men alike to grumble at the base restrictions. Clubs and recreation centers were slow in going up and lame once they were finished. As a result, “the need for social outlets,” as Jay put it, “soon loomed large on the trouble chart.”

The solution? According to the camp newspaper, it was dances.

The inaugural edition of the paper had come out on December 18th, with a bold-faced question, “What’s My Name?” in place of a title and the promise of $5 for the winning answer. Inside, an article announced that the Camp’s Service Club would open just in time for Christmas. Better yet: it would kick off with a dance, complete with humans of the female persuasion.

By the time the December 25th edition rolled out, the paper had its name: Corporal Ralph Pugh had beat out more than 250 submissions—including the pack artillery’s suggestion, Donkey Serenade—to win the $5 prize with his proposal, the Camp Hale Ski-Zette. And the Service Club was officially in business. The dance had gone off swimmingly, with more than 100 women—“imported,” as the Ski-Zette put it—from Leadville, Gilman, Redcliff, the Pando Construction company, and the Camp itself in attendance.

Lest you become inordinately excited at the news, it should be noted that nearly 1,000 soldiers had also been on hand, vying for positions on the lucky ladies’ dance cards.

Dances would become a staple of Camp Hale social life. David Little, an advisory board member who has spent decades interviewing 10th Mountain Division veterans, notes that while they may have provided brief moments of levity for the soldiers, they did little to alleviate their underlying loneliness.

[David Little] The socialization impact at Camp Hale was almost non-existent for most of these guys, which is why the US Army made arrangements to hold these regimental dances on Friday and Saturday night to bring in ladies from neighboring communities so the soldiers had someone to dance with and interact with on their days off. And they would bus women in from Grand Junction, Colorado, which is, what, 90 miles away. They would bring them up on trains from Denver and out of surrounding mining communities and they would endeavor to bring in maybe 500 ladies to hold these dances. And here’s 3,000 soldiers, for example, in the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, who would love to have a chance to say hello to an eligible female and they did what they called taxi dancing. The ladies would have a number and as a soldier you would come through and draw a number for yourself, and then you had to find your lady who had the corresponding number. And then soldiers [from companies] A through C got the first dance, D, E, F, and G got the second dance, H, I, J and K got the third dance. So it was a taxi dance. The ladies danced with 10 to 20 different soldiers and might strike up a friendship with one of them, and then the evening was over and they were back on the buses and outta town. And the guys had to remember probably for 30 days before they had another regimental dance what it was like to see a female.

All work and no play makes GI Joe a dull boy. Throw in relentless pollution, bone-chilling temps and the near impossibility of a Christmas hug, and it’s no wonder Camp Hale during the holiday season of 1942 was a decidedly grumpy place to be.

But surely it wasn’t all bah humbug, right? There had to be some silver linings hiding beneath the inversion layer of that first winter.

Right. Just so you don’t think the entire experiment was a fiasco from the get-go, let’s take a moment to explore a few of the bright spots.

[Crickets]

Yep. It pretty much sucked.

One could perhaps point to the high caliber of the camp’s earliest residents as a cause for optimism, but I’m pretty sure they were grousing too.

We’ve met many of them already. Johnny Woodward and University of Oregon ski team coach Paul Lafferty joined our story way back in Episode 4, the winter before the 87th was even a twinkle in the War Department’s eye. The Swiss ski champions and mountain guides Walter Prager and Peter Gabriel, who had helped them train the 87th on the flanks of Mount Rainier, were there as well. So was the ski-jumping, cross-country skiing Wisconsonite Charles Bradley, whom we last met in Episode 6 as he was summiting Mt. Rainier.

Prager served as coach and trainer of the cross country team of the Swiss Ski Association and was running a successful ski school at Davos when he was discovered by Dartmouth college officials who were on the lookout for a new coach. After serving several months in the Swiss Army, he arrived in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he succeeded Otto Schniebs as Dartmouth’s ski coach. He would coach the team for 17 seasons, from 1936 through 1957, with the exception of 1941-1945, when he served with the 10th Mountain Division.

After joining the Army in 1941, he was temporarily discharged to work with famed Dartmouth skier Dick Durrance as a civilian ski instructor training army units in Alta, Utah. He returned to Ft. Lewis in time to help instruct the troops of the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment in Mount Rainier National Park’s Paradise Valley. During this time, he placed second in the Silver Skis race on Mt. Rainier.

He continued to instruct with the mountain troops all the way through their deployment to Italy in late 1944. In 1945, he won the Bronze Star for valor in action in the Apennine mountains. In 1948, he was named head Alpine coach of the U.S. Olympic Ski Team for the games in St. Moritz, Switzerland, coaching all four events: downhill, slalom, cross-country and jumping.

In 1942, he was drafted into the Army and joined the 1st Battalion (reinforced), 87th Mountain Infantry Division at Ft. Lewis, Washington, where he became a key ski instructor. In May 1942, he led a test expedition of eight to the summit of the 14,408 foot Mt. Rainier. Shortly thereafter, he participated in the Army’s test expedition to Denali, North America’s highest peak, to test clothing and gear. The team made the third ascent of the peak in the process.

According to 10th Mountain Division officer John Woodward, Gabriel and fellow Swiss emigre Walter Prager advocated adopting the Swiss technique for military skiing with packs, without the upper body rotation of the Arlberg technique that the Austrian instructors at Camp Hale favored. During summers at Camp Hale, Gabriel and Prager likewise were the chief instructors for the MTC Mountaineering School, teaching the climbing instructors who then taught the techniques to the ranks.

After the war, Gabriel was involved as a civilian instructor and administrator in creating the Arctic Training Center in Fort Greely, Alaska, where the military trained troops in cold weather warfare. That unit was later renamed the Army Cold Weather and Mountain School and moved to Fort Wainwright, also in Alaska. Gabriel died about 1968, and was memorialized by the naming of the Gabriel Auditorium at Fort Greely.

To this roster of old stalwarts—if men in their twenties can be called old—came a fresh wave of recruits who would guide the mountain troops to competency, and, in doing so, help redefine outdoor recreation in America. Among them were legendary climbers like David Brower, Joe Stettner, and Fred Beckey. But in 1942, there were far more skiers than climbers in the United States, and Camp Hale carried a distinctly skiing-centric vibe.

Dartmouth College, the undisputed skiing powerhouse of the day, boasted a disproportionate presence. In addition to Coach Prager and Charlie McLane, who’d captained the 1941 team, no fewer than 62 current or former Dartmouth students would fill the ranks by the time John McCown arrived in camp. As McLane put it in a June 1943 article for the college’s alumni magazine, “On some days … it isn’t possible to drive the length of [a] street— not because of the mud, though there is plenty of it in the valley when the snow melts above, but because you can’t help meeting anywhere from five to fifty old friends….”

There was 24-year-old Percy Rideout, who had been McLane’s predecessor as captain, and who had stepped into Prager’s shoes as coach after the Swiss skier had joined the mountain troops, as well as 25-year-old Johnny Litchfield, a Maine native who had earned a spot in the 1937 World Championships and qualified for the 1940 winter Olympics, only to see his dreams of gold dashed by the war.

And there were men like Phil Puckner, the 20-year-old John had met on the train. Phil, who had grown up in Wausau, Wisconsin, a logging town on the Wisconsin River known for its rolling hills and cold winters, had quickly risen to prominence on Dartmouth’s ski team, competing in all four disciplines with a relentless work ethic and natural talent. When war broke out, Phil had enlisted with the mountain troops, landing on the troop train with John en route to Camp Hale. Post-war, he’d return to Dartmouth to finish his studies, becoming Captain of the Ski Team his senior year.

On and on the list went, a veritable who’s who of American skiing. Twenty-one year old Ralph Townsend, a 5’ 2” dynamo who had skied for the University of New Hampshire, had recently risen to prominence as the Eastern cross-country champion. He was at Camp Hale; so was his older brother, Paul, who’d competed in the infamous Silver Skis race while training with the 87th on Mt. Rainier. We first met the Boston-born Harvard boy and 1936 Winter Olympic skier Bob Livermore way back in Episode 1, when he, Minnie Dole, Roger Langley and Alec Bright were participating in the historic February 1940 meeting in Vermont often credited with the Division’s inception. He, too, had joined the 87th at Ft. Lewis, and now he, too, was in Pando, serving as one of Woodward’s instructors on the slopes of Cooper Hill.

But as our advisory board member McKay Jenkins points out, it wasn’t just American skiers who were showing up at Camp Hale. As the unit’s renown continued to spread, its makeup became increasingly international.

[McKay Jenkins] Word got out to Europeans that a new mountain division was going to be formed in the United States, and a wave of world-class skiers and mountaineers from Europe began to arrive, including many from countries occupied by the Nazis, notably Austria and Norway. Some very famous individuals—literally world-class or world-record-holding skiers—came here—perhaps most famously, a Norwegian named Torgar Tokle, who held the world record in ski jumping at that point.

A short, powerful twenty-three-year-old, Tokle had been skiing since he could walk. Born in 1919 into a poor family alongside six brothers, he’d started skiing at age 3 on skis his father had fashioned from barrel staves. By age 6, he was launching himself competitively off forty-meter hills. On January 21, 1939, he’d emigrated to America, and—eighteen hours after stepping off the boat from Norway—set a new jumping record at the Bear Mountain Park Tournament in New York. The following weekend, he set another.

Born in Løkken Verk, Norway, Tokle began skiing at three and was competing on forty-meter jumps by six. In 1939, he immigrated to the United States, settling in Brooklyn, New York. Over the next six years, he won 42 of 48 ski jumping tournaments and set 24 hill records, earning the nickname “the Babe Ruth of ski jumping.” He won three consecutive titles at the Harris Hill Ski Jump, permanently retiring the coveted Winged Trophy in 1942.

Later that year, Tokle enlisted in the U.S. Army and joined the elite ski troops of the 10th Mountain Division. He played a key role in training soldiers in mountain warfare, earning admiration for his unassuming leadership. In March 1945, during the battle for Iola di Montese in Italy, he was killed in action while leading an assault on a German stronghold.

Honored posthumously, Tokle was inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame in 1959. His younger brothers, Kyrre and Arthur Tokle, carried on his legacy as prominent ski jumpers and coaches.

Tokle’s American debut turned into a sensation. The Norwegian flew through the air “as graceful as a bird,” raved the papers about the latter event, “hit the lower slope of the landing hill, proceeded smoothly along the out-run and completed his brilliant performance with a Christiana that won the admiration of both the spectators and other jumpers.”

In his first winter stateside, he won seven out of eight tournaments. At the international tryouts in Berlin, New Hampshire, he competed before a crowd of 30,000. The following week, at the Eastern Championships, he went head-to-head with Reider Andersen, considered the world’s most stylish jumper, battling to a draw. By 1940, Tokle had won everything except the national title. In 1941, he claimed that too. Hitler’s invasion of Norway had given him a deeply personal reason to join the Army, and now there he was, in the Pando Valley, part of Camp Hale’s growing cast of mountain superstars.

Yet if you had asked Tokle or Livermore or Prager or Brower or any of the other skiing and climbing celebrities for their first impressions of Pando, they might well have echoed Burton’s assessment of the place as a disaster.

Brower, for one, couldn’t even find solace in the mountains surrounding camp. The Colorado air didn’t “ring right,” he wrote in the November 1942 edition of the Sierra Club Bulletin—and while the Rockies might have been beautiful, the smog put a damper on their charm. “I must come back some time when I can see them,” he groused. He even dissed the snow, which he compared to chewing gum.

And as if all the aforementioned warts, hiccups and personality tics plaguing Pando that first winter weren’t enough, The Mountain Training Center faced a slew of additional issues as well, some of which had dogged the unit since its start.

Brower and his peers had volunteered to serve their country, and they’d specifically asked to be in the mountain troops because the mountain troops needed their expertise.

“These men did not expect an easy life—a Sun Valley vacation in the Army,” Jay wrote. They “were real skiers and real mountaineers, with years of experience behind them, ready and willing to take all the physical hardships that necessarily form part of the daily routine in the life of a mountain trooper. All they ever asked was a fair chance to advance with the line soldier.”

They didn’t get it. Advancement in the Army was a by-the-book affair—and the mountain troops’ chapter was still being written. The specialized nature of the unit had collided with the traditional military framework once again—and to understand just how this played out, you need to understand the Table of Organization and Equipment, and for that, we turn to our advisory board member Lance Blyth.

[Lance Blyth] The Table of Organization and Equipment, sometimes called a TO&E (or simply TO), is the specified organization, staffing, and equipping of a unit. It is a list of everyone by rank, by specialty, and by the numbers that can be assigned, as well as everything—such as weapons and gear—that a unit should have and can have. It sets the standard for what a unit is supposed to have but also establishes a ceiling for what it can possess. Rolfe actually had a TO&E for a mountain division. Remember [General] Twaddle, back in early 1941? He began developing this table of organization early on because he realized how much time it would take to complete it.

Unfortunately the Table of Organization in Rolfe’s possession had yet to catch up with the unit’s rapid development, which left a number of key elements in a holding pattern.

[Christian Beckwith] Talk to us a little bit about the lack of any sort of technicians’ ratings for mountaineering and ski and climbing instructors and its connection to the TO&E.

[Lance Blyth] Yeah, and that is probably Rolf’s fundamental problem at this point in time. Late 1942, early 1943, he does not have a Table of Organization for the instructors, so he has no place to put them. It was intended that you could get people and promote them and reward them for doing their job vice the line they were holding on that TO. For example, if you didn’t have room for a sergeant in the unit, you couldn’t promote anyone to sergeant. So that was what Rolf is trying to do.

So they try for… until the spring of ‘43 to create in the US Army “mountain guides” as a technical rating. It’s just too hard and they just—they never get it approved. They just say, no, we’re not going to do it. So many of these instructors, very highly skilled people, will remain as privates the entire war. They want to be instructors. That’s what they’re good at. They’re never able to reward them or promote them beyond that.

Rolfe had given it his best shot: in early October, a month before relocating the MTC to Pando, he had formally requested ratings for climbing and skiing guides that would have allowed him to promote them. But the Army, mystified by the concept of a mountain unit in general and mountain instructors in particular, had failed to acquiesce. Predictably, morale plummeted even further. As Jay observed, “Men who had come in full of enthusiasm gradually became embittered and soured by a system that punished those it should have rewarded.”

And all this continued to play out against the backdrop of the MTC’s ongoing identity crisis.

“If a casual observer had dropped in on Camp Hale during the winter of 1942-43,” Jay noted, “and asked the first trooper he met just what his training mission was, the answer would have been, ‘Learning how to fight in the mountains.’ If he had gone further and questioned … the commanding general himself, he might have been given a more detailed statement, but the basic answer would not have changed.”

Uncertainty is stressful . For young men intent on fighting a righteous war on their country’s behalf, the unit’s ambiguity left their own sense of self in a disorienting state of limbo. Some of the boys they’d grown up with had already thwarted Japanese expansion in the Pacific with the battle of Midway and participated in the Allied invasions of Sicily and North Africa. All they wanted to do was fight. But as they continued to stumble through their maneuvers in search of their purpose, a collective anxiety settled over Pando’s residents to the detriment of morale and performance alike.

There was also the not-insignificant matter of personnel.

[Lance Blyth] By 1942, as all is taking place when McCown is at Officers Candidate School. The United States is running into a manpower crisis. It’s 300,000 men short of its planned mobilization numbers for that year. It had underestimated how many men it would take to keep the factories running—hadn’t expected to send a whole bunches of stuff to the Soviet Union. So if they needed more people in industry than they had thoughts, they could not draft and mobilize as many.

By the holiday season, Pando was welcoming hundreds of new recruits a day. While the influx wasn’t enough to activate a full mountain division, it might have been a promising start—had all the newcomers been like Phil Puckner. They weren’t. Eighty percent of them were more like Buddy. As with every other unit in the Army, the Mountain Training Center needed men, ASAP, and quantity took precedent over quality. As a result, the great majority of the new recruits came not via the National Ski Patrol Systems’s careful recruitment process but from bases in the south, in particular, the 31st Division from Louisiana, the 30th from Memphis, and Buddy’s unit, the 33rd Division, from Camp Forrest, Tennessee.

“It was unfortunate,” Jay wrote, “that these particular divisions happened to father the first full-scale Mountain Troops.” Unaccustomed to the challenges of the mountains, southerners like Buddy struggled to adapt. “Over half the men in the 110th Signal Company eventually had to be transferred,” he continued, “because they could not take the cold climate, high altitude, and the rugged mountain life.”

As the southerners trickled in, it was clear to the Mountain Training Center’s instructors that they would have their work cut out for them. “A group of new recruits arrived from Camp Barkeley, Texas, to join our company,” reported the May 19th issue of the Ski-Zette. “They arrived in the evening in the midst of a snowstorm clad only in their sun-tans.”

Rolfe had repeatedly requested rugged, outdoorsy types who could take the mountain life regardless of prior experience. What he got instead were “raw recruits” direct from induction centers—men ill-prepared for the rigors of mountain living or mountain warfare. The result was as frustrating as it was wasteful. The new soldiers needed basic training; they also needed mountain training, for which Rolfe needed veterans from the 87th, but there weren’t enough of them to go around. The qualified personnel who were available could either put the new recruits through boot camp, which meant postponing mountain training for three months, or combine the two. Neither was a good solution.

And everyone who walked through Camp Hale’s gates needed to be fed, housed, clothed, and equipped. When recruits failed to make the cut, all the resources the Mountain Training Center had just invested in them went down the drain. It was a mess.

Did we mention that much of the specialized equipment being developed by Bates, House, and Robinson at the Quartermaster General’s office had yet to arrive?

If this were a movie, you can imagine the setup:

The camera pans over the imposing Pentagon, then swoops through its wrought-iron doors. Footsteps echo sharply as the lens focuses on a red-haired figure, mid-40s, striding briskly down a polished corridor. A Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart gleam faintly on his uniform .

The man enters a small, windowless room, where a suited bureaucrat sits behind a metal table.

“Colonel Rolfe,” he says, sliding a folder across the table.

Rolfe glances at the folder but doesn’t move.

“You will build a test force with no precedent and minimal support, under conditions that will make most men quit.”

Rolfe’s expression remains unchanged.

“You’ll rely on civilian athletes—men with no military background—to train thousands of soldiers who’ve never seen snow.”

He opens the folder. One sheet of paper.

“All this will be done at 9,200 feet, amidst toxic air and extreme conditions. Direction from your superiors will be inconsistent, inadequate, and contradictory.”

Pause.

“Any questions?”

Rolfe studies the paper briefly, then looks up.

“No, sir,” he says, his jaw tightening. He exits, his polished boots echoing in the corridor.

Cut to a wide shot of snow-choked peaks. An isolated base sits battered by wind and cold. A title card slams onto the screen:

Camp Hale: Mission Impossible.

Yeah, alright, you get the picture. But let’s be honest: if you’d been stuck at Camp Hale that first winter alongside General Rolfe and David Brower and Johnny Woodward and the rest of the unit, you might have been more than a little dubious of your chances too.

Woodward hadn’t sugarcoated a thing in his letters to John McCown. The smog, the altitude, the recruitment problems, the flagging morale—it was all there, laid out in blunt, unvarnished detail. But beneath the frustration John detected something deeper: an unshakable belief in General Rolfe, and the conviction that from this mess, something greater could be forged. To Woodward, the problems weren’t setbacks. They were tests. And failure was not an option.

John felt the same.

As he stepped off the train in Pando and shifted his rucksack, his mind was already racing ahead. The chaos and disorganization? Temporary. The bureaucratic blunders and raw recruits? Manageable. The disaster of Camp Hale’s opening didn’t matter. What mattered were its lessons, and how they would shape what came next.

His eyes swept the depot. Recruits huddled in self-selected groups, stamping their feet against the cold, their breaths rising in ragged clouds. Beyond them, soldiers in oversized white parkas trudged between buildings like ghosts, skis slung tips-down over their shoulders, faces buried beneath layers of wool. Snow piled high against the white-sided barracks. Above them, the mountains loomed, their ridgelines blurred by smog, silent and indifferent to the men below.

John spotted Phil Puckner among the college boys, his face alight with excitement, anticipation, and curiosity. A few yards away, Buddy stood with the Southerners, hands jammed deep in his pockets, his expression hovering between doubt and something closer to fear.

John had a better sense than they did of what lay ahead—the endless drills, the brutal cold, the lessons etched in sweat, exhaustion, and frostbite. But even he couldn’t grasp the adversity they’d endure, or the impact it would have on them, and the country they’d sworn to defend.

He inhaled. The sub-zero air mixed with the acrid bite of coal smoke as it filled his lungs. Tightening his shoulders against the cold, he turned to the recruits.

“Well, boys,” he exhaled, his voice cutting with authority through the brittle chill. “Welcome to your new home.”

But it wasn’t home—not yet. The encampment’s buildings, its drills, and the instruction that would transform the test force into America’s first full mountain division were still taking shape. Home would come later, rising from the unforgiving lessons of the Colorado Rockies and the bonds forged in their shadows. For now, there was only the snow, the cold, and the first uncertain steps toward a future that would change us all.

“And thus,” Jay wrote, “did the Mountain Training Center get its start, among the snowdrifts and unfinished buildings of Pando.”

[line break]

And that concludes today’s episode. Thank you for listening.

If you want to take your appreciation of the 10th a step further, don’t miss out on this year’s Ninety-Pound Rucksack Challenge, our annual ski mountaineering tribute in honor of the 10th and its contributions to American skiing. 2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the 10th’s historic World War II ascent of Riva Ridge, and we’re excited to announce ski areas around the country will be hosting the Challenge on February 18th at 7 pm local time on their slopes, including Vail, A-Basin, Ski Cooper, and Steamboat Springs in Colorado, Whiteface Mountain and Snow Ridge in New York, Mad River Mountain in Ohio, the Dartmouth Skiway in New Hampshire, White Pass in Washington, and Mt. Hood SkiBowl in Oregon. We’re also excited to welcome our new partners, The National Ski Patrol and Uphill Athlete, and of course I’ll be doing the Challenge right here on Mt. Glory in Jackson Hole. I hope that you will join me.