The Origins of Camp Hale: How the U.S. Army scouted, selected, and developed Colorado’s high-altitude Pando Valley site to create a training ground for mountain warfare.

Episode Synopsis:

In Episode 11 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack, host Christian Beckwith explores the origins of Camp Hale, the high-altitude training ground where the mountain troops were transformed into the elite mountain warfare unit of the U.S. Army. Nestled in Colorado’s Pando Valley, Camp Hale wasn’t just any military base—it was a place where soldiers would develop the skills and toughness needed to fight in Europe’s mountains during World War II.

The episode covers the decision-making process behind the camp’s selection, the incredible logistical challenges of building it, and the impact it had on both the 10th Mountain Division and the nearby town of Leadville. As we follow the personal journey of John Andrew McCown II, a climber-turned-soldier, we get a glimpse of the broader legacy of Camp Hale, not only in military history but also in shaping post-war outdoor recreation and skiing in America.

The episode includes interviews with:

- Lance R. Blyth: Command Historian of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM); Adjunct Professor of History at the United States Air Force Academy.

- Chris Juergens: Curator, National World War II Museum.

- Sepp Scanlin: military historian and museum professional; served as the 10th Mountain Division and Fort Drum Museum’s Museum Director.

- Lou Dawson: Author, Colorado ski mountaineering pioneer

Key Points:

- Origins of Camp Hale: How the U.S. Army scouted, selected, and developed the high-altitude Pando Valley site to create a training ground for mountain warfare.

- Key Figures: Brigadier General Harry Lewis Twaddle and Colonel Onslow Rolfe were instrumental in bringing Camp Hale to life.

- Challenges of Construction: The environmental and logistical challenges involved in building a base for 15,000 soldiers and 5,000 mules at 9,200 feet in just seven months.

- John McCown’s Story: The personal journey of John Andrew McCown II, a climber-turned-soldier, whose rise through the ranks paralleled the evolution of the 10th Mountain Division.

- Leadville’s Origins & Relationship to Camp Hale: The rich history of Leadville, once a booming silver mining town, and how the proximity to Camp Hale redefined its role during WWII. The town’s “triple iniquities” (saloons, gambling, and prostitution) posed unique challenges for the military, leading to a strained yet interdependent relationship between the base and the community.

Featured Segments:

- Opening Segment: Christian Beckwith introduces the episode and highlights the significance of Camp Hale in the 10th Mountain Division’s history.

- Interview with Lance Blyth: Military historian and Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board member Lance Blyth discusses the requirements for selecting Camp Hale and the challenges involved in its development.

- On the Ground: A vivid description of the construction process at Camp Hale, bringing to life the stories of the workers, engineers, and military personnel who made it happen.

- Expert Insights: Ninety-Pound Rucksack Advisory Board members Sepp Scanlin and Chris Juergens provide context on the camp’s construction and its impact on Leadville, Colorado, while Colorado ski mountaineering pioneer Lou Dawson describes the topography and climactic challenges of Camp Hale.

- John McCown’s Journey: A narrative that ties McCown’s personal climbing experiences to his role in the formation of the 10th Mountain Division.

Partnership Acknowledgements: We’d like to thank our partners, without whom this podcast wouldn’t be possible: the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, Denver Public Library, The American Alpine Club, 10th Mountain Division Descendants, and the 10th Mountain Alpine Club. Their continued support helps us uncover and share the rich history of the 10th Mountain Division.

Sponsorship Acknowledgements: Special thanks to our sponsors for their generous support of Ninety-Pound Rucksack:

- CiloGear: Makers of the best alpine backpacks in the industry. Get 5% off your purchase and support the 10th Mountain Alpine Club by entering the code “rucksack” at checkout at cilogear.com.

- Snake River Brewing: Wyoming’s oldest and America’s most award-winning small craft brewery. Whether you’re enjoying an Earned It Hazy IPA or celebrating with a Dirty 30 IPA, Snake River Brewing is the perfect après-adventure beer. Visit their brew pub in Jackson or find them in stores throughout Wyoming, Idaho, Colorado, and Montana.

Patron Support: We want to extend a heartfelt thanks to our growing community of patrons, who make this podcast possible through their support.

————

EPISODE 11: CAMP HALE, PART 1

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and I’m so glad you’ve decided to join us today, because we’re about to embark on one of the 10th Mountain Division’s most famous chapters: the selection and development of Camp Hale, where the unit’s mountaineering identity would be forged in the shadows of Colorado’s highest peaks.

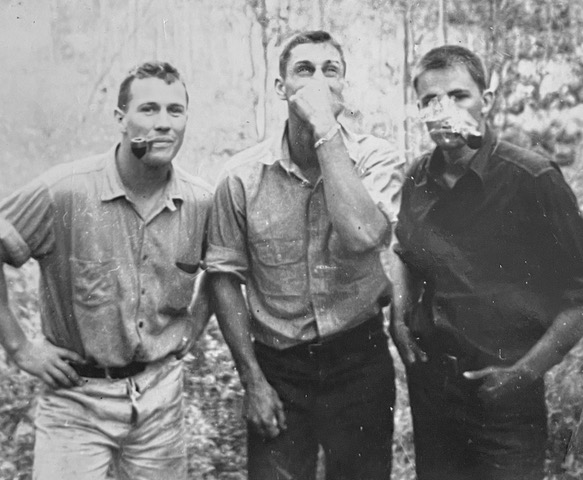

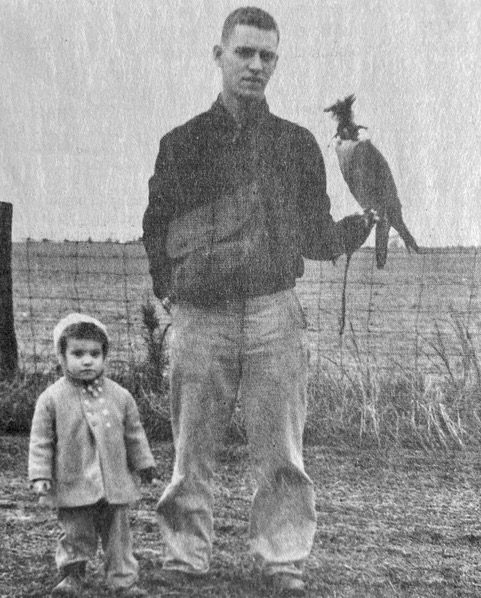

If you’re just joining us, Ninety-Pound Rucksack is the real-time research for a book I’m writing about the 10th Mountain Division and its impact on outdoor recreation in America. The book will recount the 10th’s story from the perspective of John Andrew McCown II, a young falconer from Philadelphia who learned to climb in the Tetons, joined the mountain troops after Pearl Harbor, and went on to engineer its signature offensive, the 1945 ascent of Riva Ridge that broke Hitler’s Gothic Line and helped precipitate Germany’s surrender of Italy. As those of you who have been following along for the past two years know, the podcast is my effort to master all aspects of the Division’s evolution so that I can recount its story while creating a historically accurate portrait of John’s journey through its ranks.

I wouldn’t be able to do any of this without the support of our partners, the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, The American Alpine Club, the 10th Mountain Division Descendants, and our newest partner, the 10th Mountain Alpine Club a collective dedicated to advancing alpinism in the 10th Mountain Division community.

I also wouldn’t be able to do this without the support of our sponsors, CiloGear, and Snake River Brewing.

Any great mountain adventure deserves a great pack, and if you’re in the market for the lightest, most durable, best-fitting alpine backpack that money can buy, CiloGear has you covered. I’ve been using my CiloGear Worksack for a couple of seasons now, and my appreciation for its attention to detail has deepened with every climb. As much as I love its bombproof construction and impeccable fit, I love the fact that it never gets in the way of my climbing even more. It does everything I need it to do when I need it—and the rest of the time, I never notice it’s there.

CiloGear is 100% owned & operated in the US , and if you go right now to their website at cilogear.com—that’s c-i-l-o-gear.com– and enter the discount code “rucksack,” you’ll get 5% off and they’ll make a matching donation to the 10th Mountain Alpine Club.

Snake River Brewing is Wyoming’s oldest and America’s most award-winning small craft brewery. I developed a taste for their beers in 1994, the year the Snake River Brew Pub opened here in Jackson. I was one of their dishwashers by night, but by day, I was in the Tetons, and I always reached for a Snake River beer after every adventure. Thirty years later, I still do. Now, with distribution across Wyoming, Colorado, Idaho, and parts of Montana, you can too.

Whether you’re refreshing yourself with an Earned It Hazy IPA or celebrating their 30th anniversary with a Dirty 30 IPA, discover the taste of adventure with Snake River Brewing. And when you’re in Jackson, swing by the Brew Pub for some good vibes, killer brews, and delicious grub. Serving breakfast, lunch and dinner 7 days/week. Check them out at www.snakeriverbrewing.com.

Most of all, I’d like to thank our community of patrons. Patrons are more than just listeners—they’re a crucial part of our effort. Their contributions help cover the costs of research and production, ensuring that we can continue delivering a factually accurate, high-quality story. As a token of our appreciation, we provide patrons with access to bonus content we develop exclusively for them.

Becoming a patron is the best way to support the show. But you can also tell your friends about it, give us five stars on your podcast app, leave a review, and get social with us on Instagram, LinkedIn and Facebook. Trust me when I say that every little bit helps.

And now, let’s catch up with our protagonist as he prepares to make the first first ascent of his young life.

[line break]

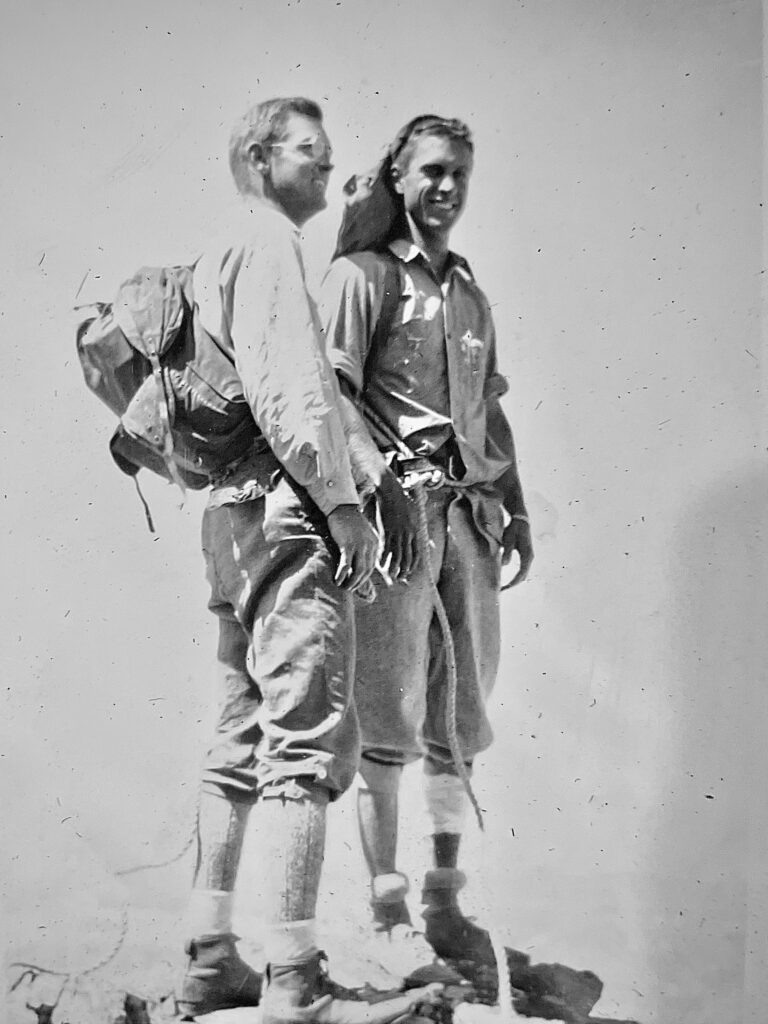

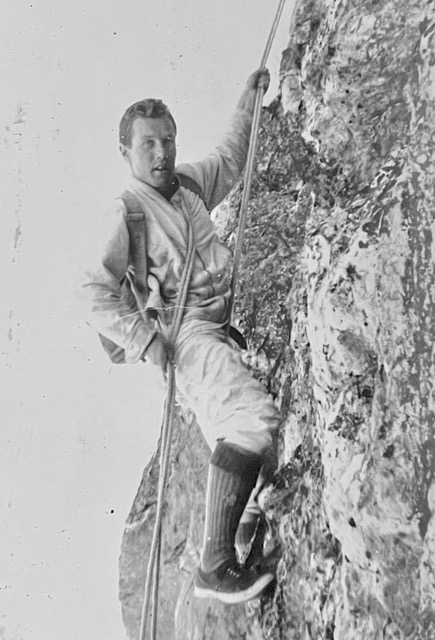

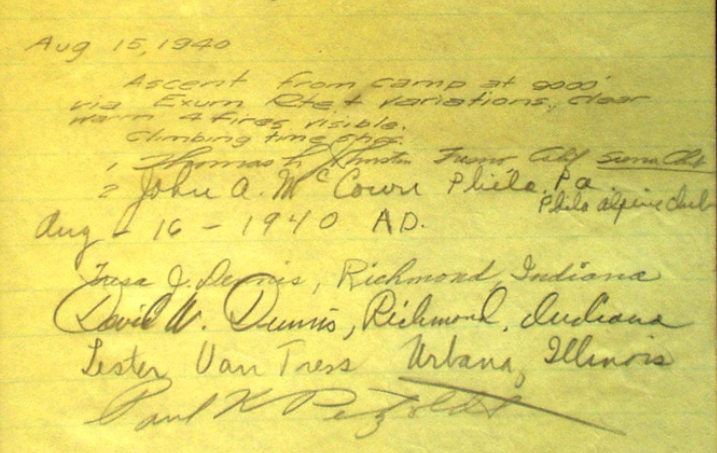

John McCown seated his left foot on a protrusion, pressed his right against a flake, and stabilized himself into a hands-free stance at the base of the vertical wall. It was August 9, 1940, and John, twenty-two years old and recently graduated from Wharton, was nearly a mile above Moran Canyon, at 11,000 feet on an unclimbed peak in the northern reaches of the Tetons. All that remained between him and the top was a fifty-foot, north-facing summit cap. It didn’t look difficult, particularly after what they’d been through earlier in the week, but he was meticulous about every aspect of his climbing, both because he didn’t want to die, and because he had more than just himself to think about. Though he could no longer see them below, his younger brother Grove and their friends Ed McNeill and Ponto Edwards were awaiting his call in the ridgeline notch where he’d left them. There were times to be bold. A day’s hike from help wasn’t one of them.

He fished a flat steel piton from his pocket, seated it in a thin crack above his head, and began tap-tap-tapping it in with his hammer. The deeper he drove the piton, the more resonant the sound, until with one last satisfying thwack he sank it to the eye and it pinged back with reassuring solidity. He pulled out a four-foot piece of cord, threaded it through the eye, looped it around the lead rope, and tied it off with a fisherman’s knot. Satisfied with his work, he slipped the hammer back into its holster and studied the moves ahead.

The vastness of the landscape stretched out around him like a four-dimensional map. Far below, to his left, a spherical lake ringed by steep talus walls gathered shadows with the advance of day. To the northeast, a ridgeline, spiny as a dragon’s back, dropped 3,000 feet into the canyon’s depths. The flat summit of Bivouac Peak was just visible above the dragon’s spine. Overshadowed by the hulking massif of Mt. Moran, Thor Peak rose to the east, its pyramidal summit awash in light. Moran’s southern flanks and Bivouac’s northern ridgelines plunged to the canyon floor like towering gates, framing the glittering waters of Jackson Lake.

As John analyzed the terrain above, he played out the moves against his protection and the implications of a fall. About twenty feet up, the wall seemed to yield to a steep, east-facing slab. Splotches of green and black lichen dotted the textured rock like splattered paint. The crack system split in a Y; it looked like he could use the left fork to hand traverse to the slab, working the footholds for balance.

He pulled himself back into the rock, took a deep breath, slotted his fingers into a constriction and began to climb. Bumping his left foot up to a small shelf, he transitioned his weight onto the felt soles of his kletterschuhe, torqued his fingers in the crack to stabilize himself, high-stepped, then slid his hand up the slab until he found a positive edge. The piton was by now ten feet below him, which meant that a fall would have sent him twenty feet into the broken rock at the base of the wall. But the edge was good, the severity of the angle had lessened, and he knew without thinking about it that he could make the moves.

This is what he loved about climbing: the decision-making, and the single-minded focus it entailed. Figuring out protection, evaluating features, weighing the consequences, and committing to a route demanded a concentration that was absolute. The harder the climb, the deeper he had to dig to process all the variables. Once he began moving, everything else disappeared, leaving him alone with the rock.

But it was more than just focus. In the middle of a crux, fragments of his life would pierce his concentration like a ray of light in a darkened room. A lingering thought—his brother Andrew’s sad, sweet face, his mother’s emotional retreat, the escalation of his father’s implacable demands—would slip into his mind to shadow his exertions. At the belay, as his breathing subsided while he assembled an anchor, he’d find that he’d made peace with something that had been vexing him for days, weeks, months. Afterward, he could replay the subtleties of the movement and the clarity of his realization in intimate detail. He’d never experienced anything like it.

John continued up the smooth slabs, padding around the lichen patches. The climbing required diligence, but it was too easy to give him the laser-like focus he’d come to crave. After half a dozen moves, the angle backed off, and he scrambled the remaining twenty feet to the top without placing another piton.

To the south, a cleft in the summit dropped away to a narrow saddle. Beyond it rose another steep rib, a horizontal column of golden rock radiating warmth in the midday sun. Beyond that, the iconic summits of the Cathedral Group—Teewinot, Owen, the Grand, Middle, and South Tetons—dominated the horizon. John could just make out the summit of Woodring in the eastern foreground, scene of the crazy 4th of July ski race Fred Brown had roped them into eleven months earlier. He marveled at how much had changed since then. An image of Margaret Smith’s playful smile bubbled up, leather belt cinched tight around her Levis as she glanced over her shoulder at him on their way to Woodring’s base. To the west of the Cathedral Group lay Table Mountain’s breadloaf-like summit, where he, Grove, and Ed had encountered a group of 101 Boy and Girl Scouts on top. The rounded features of the South Teton bumped up against the Middle’s sharper edges, and John thought of Grove’s brown eyes, wide behind his wire-rim glasses, as he’d hauled him onto a ledge. It had been the first real mountain they’d ever climbed, and the start of a new chapter in their brotherhood. Everywhere he looked, he saw memories.

The summit was too pointy to stand on, so John swiveled, sat, and balanced his butt on the east side of the block. “Off belay,” he called, using the signals Teton guide Paul Petzoldt had introduced to the range. He pulled up the rope, coiling it around his knees, then looped it over his shoulder and braced himself as best he could.

“On belay!”

As he waited for the rope to move, he took in the view. To the west, in Pierre’s Hole, Idaho, and north beyond that, toward Yellowstone, smoke plumes rose from four distinct fires, gray tendrils twisting into the clear blue sky. Bivouac’s south face soared above Jackson Lake. A few days earlier, they’d made it 1,500 feet up the 2,000-foot wall. It had been the most ambitious adventure he’d ever undertaken, on one of the biggest unclimbed features around, and he wanted more.

After a summer in the Tetons, his senior year at Wharton had felt tedious. The sports he’d loved growing up—football, track, baseball, lacrosse—had come to seem simplistic. He still appreciated the short bursts of activity they required and the strength and endurance he’d developed in their pursuit, but compared to climbing’s all-encompassing burn, they felt silly, almost childish. Even his falconry, which had provided him solace and escape after Andrew’s death, no longer held his interest. He’d given his Cooper’s Hawk to his brother Dick and buried himself in his studies—but his thoughts were consumed by climbing.

The best way to train for climbing was climbing itself, but that was in short supply around the UPenn campus, so as fall turned to winter, he’d traversed back and forth on the protruding stone edges of Houston Hall, run miles after dark in the rain and sleet, and carried hundred-pound loads of water up and down the stadium stairs of Franklin Field. Before bed, he did pushups, pullups, and sit-ups to exhaustion. Even his senior thesis, on the economic importance of Jackson Hole, had doubled as research for his climbs. As he’d pored over state and county financial reports, he’d laid out maps and photos of the Tetons on the library’s long wooden desks, piecing together what was known—and, more importantly, what wasn’t—about the range.

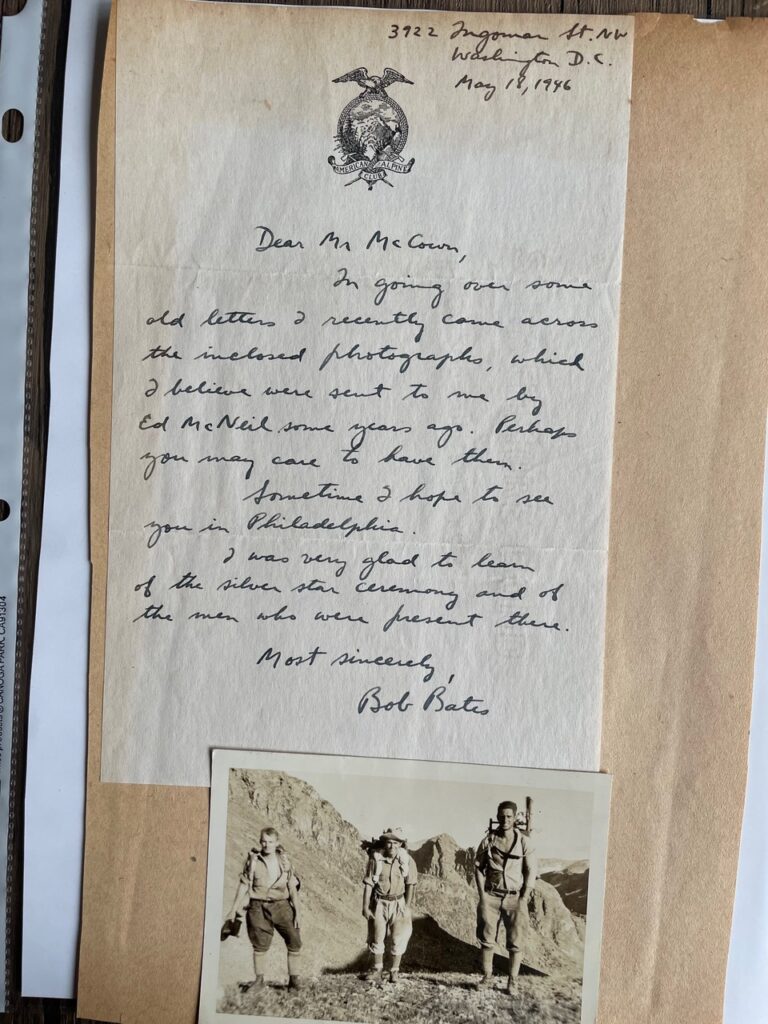

A chance encounter in July, soon after they’d set up their tents in the Jenny Lake Campground, had alerted him to Bivouac’s potential. In 1938, five of America’s top alpinists—Bob Bates, Bill House, Paul Petzoldt, Dick Burdsall and Charlie Houston—had attempted K2, the second-highest mountain in the world, in 1938, reaching the hitherto unheard-of height of 8100 meters. Bates and House had shown the film of their attempt in the campground, and John had watched the grainy black-and-white footage flicker across the makeshift screen with a mix of wonder and awe. Cloaked in ice and shattered stone, exotically remote and impossibly high, the Karakoram giant seemed incomprehensibly removed from the familiar profile of the Tetons, and yet Bates, House, Petzoldt and their teammates had nearly made the summit.

As Bates recounted their harrowing attempt, John had felt a magnetic draw to the audacity of their struggle. He’d approached Bates afterward, and when they’d discovered they shared an alma mater in the William Penn Charter School, Bates had invited him to their campfire. John’s fascination with K2’s lethal beauty and his obvious admiration for Bates and his partners seemed to amuse the smiling, skinny man. “You know,” he’d chuckled as embers danced into the night, “if you really want an adventure, you should have a look at the south face of Bivouac. The rock looked pretty clean. I don’t think anyone has been on it.”

Impossible to see from the valley floor, Bivouac’s south face rose from the lodgepole pine forests and huckleberry brambles of Moran Canyon in a sweeping escarpment of banded rock and broken buttresses. Bates had studied it while climbing the north ridge of Mount Moran. John had been floored by his suggestion. To have one of America’s best alpinists propose an unclimbed wall to a second-year climber like him was as intoxicating as it was irresistible. He’d immediately taken the idea to Ed, who shared his obsession, and they’d begun plotting their attempt. Grove, who idolized his brother, and Ponto, who had never climbed anything higher than a tree, had initially shared their excitement, but as the scope of the objective became clear, they’d grown increasingly quiet.

The four friends had left the campground mid-morning and made their way through the forest around the east side of Leigh Lake. The further they’d traveled, the more the trail had deteriorated, and they’d soon found themselves climbing over, around and under downed timber. By the time they’d entered Moran Canyon, their approach had slowed to a crawl. They’d bushwhacked their way through thickets of cottonwoods and huckleberry brambles, yelling out in fake jest —”Hot dogs! Get your hot dogs here!” — to scare off the grizzlies Grove was convinced were lurking in the underbrush.

Bivouac’s south face steps up along a ramp of steeply angled talus. They’d arrived at the base of the ramp in the early afternoon, sweating profusely and scratched and bleeding from the approach. While Grove and Ponto stayed behind to set up camp, John and Ed had dumped their loads and hustled higher for a better look. Puffing up the shifting talus, they’d craned their necks until Ed had spotted a weakness in the middle of the face where the verticality relented into a series of dihedrals and chimneys. John, swatting flies with one hand, had traced out a potential route with his index finger. By the time they’d returned to camp, Grove and Ponto were building a fire for dinner, and John and Ed had decided on a plan of attack.

They were sorting their equipment at the base of the wall when the first blush of dawn illuminated Moran’s summit. Grove tended to get “nervous,” as he put it, and it was Ponto’s first real route, so John had gone first, fighting his way up a dirty dihedral, brushing lichen from the rock and banging suspect holds with the palms of his hands to test reliability. As the morning light began to wash out, Ed had taken over, working his way into a recessed chimney that shed debris into his eyes and mouth with every move. The pair had continued swapping leads, zigging around sections of loose choss, zagging to avoid the overhangs that dotted the face like eyebrows and bringing Grove and Ponto up on tight ropes.

The higher they’d climbed, the more exhilarated John had felt. Each loose block he’d sent soaring into space, every precarious foothold that amplified the exposure beneath his heels had unlocked a deeper sense of freedom. He’d waited a year for this. The reality was even more intoxicating than he’d dared to dream.

As the shadows of the peaks had crept across the valley floor, John had climbed into a crack system only to discover, thirty feet out from his last piton, that the crack was actually a flake. The higher he’d climbed, the more the flake had flexed, until finally the piton simply fell out, leaving him, in essence, soloing. Too far from his last protection to downclimb, his only option had been to keep going. With a deep, guttural yell, he’d liebacked up the remaining twenty feet, then thrown for a thank-god hold just below a narrow ledge. By the time he’d yarded himself onto the shelf, heaving with exertion and stress, he’d felt electrified.

John had begun to develop a reputation the previous summer. One could tell just by looking at him that he was prodigiously strong, but it was his ability to make decisions under pressure that had set the campground talking. On his first proper climb, of the Grand Teton’s Exum Ridge, he had followed his partner up the route with neither a rope nor a whimper. He’d brought Grove and Ed up the mountain three days later, then, always in the lead, guided them up Teewinot and Nez Perce in quick succession. Once John made a decision, it was as if a switch had been thrown, and he moved with unshakeable confidence. It wasn’t courage, or bravery; it was just something some people had and others didn’t. He had it. Grove didn’t. Grove would appear at a belay, pupils dilated, shaking with adrenaline, and look at his older brother with a mix of terror and awe. In those moments, any pride John might have felt was outweighed by his sense of responsibility for Grove’s safety—but the rush he got from each brush with danger only heightened his appetite for more.

Ed shared his proclivities, though to a lesser degree. Grove and Ponto were another matter. Overwhelmed by the sheer scale of their undertaking, Ponto had stopped talking less than a hundred feet up the wall. Grove’s reticence had grown in direct proportion to their distance from the ground. As the sun had arced westward, John and Ed had debated the route while their partners pressed against the rock in silence. It had been nearly five when John had reeled his bespectacled brother onto the ledge. “Nope,” Grove had said, gasping for breath and clinging to the rope. “That’s it. I’m done. I want to go down.”

Down was known, pedestrian, safe. Up was uncertain and elusive, each additional move one more piece of the riddle they’d set out to solve, and John’s desire to grasp the answer in his scraped and swollen hands burned hotter than anything he’d ever known. Far from the bustle of the Jenny Lake Campground and the well-trodden summits of the Cathedral Group, the south face of Bivouac was as remote a place as one could hope to find in the Tetons. John wanted the wildness; within it, anything could happen. He wanted the mesmerizing possibility of looking up and not knowing if he could do whatever came next. The other side of knowing held the promise of something profound, and the desire to understand it lent him purpose and resolve. Pitch after scary pitch of loose and dubious climbing, he redefined his conception of what he could do, and with it, any limits he might have placed on himself.

But Grove wanted down, and Grove came first. Their brother’s death had expanded John’s sense of responsibility until it had begun to feel like part of his skin. Healing, he’d come to realize, depended on more than just him. It included Grove, of course, but Ed and Ponto were part of it too. The number of variables one encountered in the mountains was endless. Inexplicable rockfall, sudden storms, dehydration, hypothermia, the dangers of falling, of being benighted, of making one wrong decision in the course of a day filled with them: it all had to be accounted for, and the rich complexities demanded an interdependence that was critical to success. As the sharp pain of Andrew’s loss had receded, scar tissue had knotted around the space he’d occupied in John’s heart, and his partners had become part of the resulting fiber. They were a team, and as he’d reeled Grove onto the ledge, John had seen in his eyes that he’d pushed too far. He’d redirected all his energies to the descent, and they’d reached the base of the wall in the deepening gloom, pulled their ropes, and staggered down the steep talus slopes to their tents.

The veteran climbers John had met in the campground—people like Petzoldt, Bates and House—seemed to have been baptized by similar experiences. The shared excitement in preparing for a route, the doubt and fear of a challenging climb, the elation of success: all of it was inspired by the mountains, but its animating spirit seemed to flow between partners, and it lent the stories around the campfires a camaraderie that had seduced him. He’d found his people.

The rope began to move, and John leaned his broad shoulders against the weight, rocked forward, and took in the slack. As he did, he marveled at the summits and ridgelines and precipitous canyon walls laid out against the horizon. Bates’ story of K2 had sparked something new in him. They’d hiked for 350 miles just to get to base camp, then climbed for three weeks in utter isolation before reaching their high point. Now, he wanted to be in a place where there was no one for miles, for days, where the consequences of every decision lay in his hands, where he could think about Andrew in peace. He wanted the full responsibility for his own survival.

Ever since Hitler’s invasion of Poland, the edges of John’s life had begun to blur. Even the campground was marked by war. The previous summer, he’d been captivated by the Swiss mountaineer Peter Gabriel, who’d guided countless ascents of famous Alpine peaks before fleeing Hitler’s aggression. The German-American brothers Fred and Helmy Beckey, ages sixteen and thirteen respectively, had parried questions about their ascents of the Grand, the Middle, the South, Teewinot and Nez Perce in five quick days as nonchalantly as they’d recounted their parents’ escape from Düsseldorf. Bates, who’d observed Swiss mountain troops undergoing maneuvers in the Alps the summer before with his friend H. Adams Carter, had confided to John their intent to lobby the American Alpine Club to offer its services to the War Department. War had a dark and terrible magnetism to it, and the possibility of America’s engagement elicited a curiosity in John that was not dissimilar to the draw of the unclimbed peaks to the north. He felt like he was being pulled toward something momentous. He just wasn’t sure what it was.

As the rope continued to move, John watched the fires dance in the north, their pillars of smoke mushrooming in the wind. There was no way he could have known that in less than a year, the U.S. Army would begin scouting the area in their path for an encampment for the mountain troops. There was also no way he could have known that he would become one of the unit’s leaders, working alongside climbers like Bates, Gabriel, Petzoldt and the older Beckey brother to prepare his soldiers for war—or that the decision-making, the focus, the mental and physical toughness, the camaraderie and most of all his sense of responsibility for those who relied upon him would come to inform his perspective in battle as it had in climbing.

For now, though, the fires burned on, a distant reminder of the world beyond the peaks.

[line break]

John and his partners would name their mountain Cleaver Peak, after the prominent cleft in the summit cap. Bivouac’s south face would remain unclimbed until after the war, when Dick Pownall, an Exum Mountain Guide and future member of the 1963 American Mount Everest Expedition, made the first ascent with Paul Kenworthy, a future Academy Award winning filmmaker. Had it not been for a bird, John might well have had another shot at it, a few years later, with his fellow mountain troopers as part of their maneuvers.

One of the 10th Mountain Division’s great unsung heroes is Harry Lewis Twaddle, an electrical engineer from Ohio who helped plan for the US Army’s expansion in the leadup to World War II. In 1912, he had been commissioned into the Army as a second lieutenant, then posted to Fort Gibbon, Alaska, during World War I, an experience that had refined his appreciation for the rigors of cold-weather training.

In 1938, Twaddle, by now a colonel, had been assigned to the General Staff at the War Department’s Operations and Training Division, where he oversaw the preparation of soldiers and units alike for combat. He quickly became the staff’s recognized expert on training, and in mid-December 1940 he wrote a memo to the Army’s Chief of Staff, General George C. Marshall, calling for surveys of potential high-altitude sites for a mountain camp.

At roughly the same time, a senior military officer reached out to American Alpine Club vice president Walter Wood Jr. and asked him to put together a display of state-of-the-art mountaineering equipment for the Army. To assist him, Wood had tapped fellow AAC member Bob Bates. “The display and the discussion that followed obviously made an impression on [the officer],” Bates would later write in his auto biography, The Love of Mountains is Best. Indeed, he continued, it “may have triggered a letter…, on December 20, 1940, to the American Alpine Club from Colonel Harry L. Twaddle,… [asking] for information on essential items of mountaineering equipment that could be of use to the army.”

Twaddle’s Alaskan experiences coupled with his exchanges with the AAC got his wheels spinning. In March 1941, soon after being promoted to Brigadier General, he arranged a meeting with Woods and Bates to discuss their upcoming expedition to the St. Elias Range in the Yukon.

In the aftermath of the Soviet invasion of Finland, General Marshall had assigned Lieutenant Colonels Charles Hurdis and Nelson Walker to study the country’s readiness for mountain warfare. With Hurdis and Walker by his side, Twaddle grilled the two climbers on their plans, then asked for their help testing equipment for the Army.

In April, as his thinking on the matter evolved, Twaddle wrote a second memo, calling for the establishment of a proper mountain encampment. “Troops operating in mountains will normally encounter high altitudes, snow, and low temperatures,” he’d observed. “They must be accustomed to life under such conditions. The camping problems alone are tremendous. Troops must actually live and train the year round under high-altitude conditions if we are to obtain any worthwhile results. There is no case where realism in training is more appropriate.”

On the heels of Twaddle’s memos, Marshall directed Hurdis and Walker to begin investigating high mountain areas around the western US for a training site for a full division.

The activation of the country’s first mountain test force, the 1st Battalion of the 87th Mountain Infantry, was still six months away, and it would take the bombing of Pearl Harbor for Congress to authorize the sort of funding necessary to build a mountain encampment from scratch. Still, it didn’t take a genius to realize that Washington’s flat, rainy Ft. Lewis, where the 87th would begin its historic journey, wasn’t going to cut it. For one, the nearest suitable mountain terrain was located on the flanks of Mt. Rainier, half a day’s travel away. For another, the base would soon be bursting at the seams. The day John belayed his partners up Cleaver Peak, the post garrison numbered 7,000 men. By the spring of 1942, when he joined the 87th at Ft. Lewis, more than 37,000 troops from six divisions would be billetted at the base, with thousands of soldiers living out of “winterized” tents, complete with hastily assembled floors and plank side walls to protect them from mud and snow.

Finding a site for a proper mountain camp was imperative. But as Ninety-Pound Rucksack Advisory Board member Lance Blyth points out, Twaddle’s requirements for such a camp amounted to a tall order.

[Lance Blyth]

The camp had to be at elevation because they wanted to have to acclimatize to get troops used to being at altitude. And they needed enough snow and cold to be able to carry out a relatively lengthy winter training period. It had to have a flat enough of an area to build a camp large enough for 20,000 men. That’s a small city. Those are the premium in the mountains. As someone who has spent 30 minutes looking for a place just to put up a two man tent, trying to think of a place for 20,000 would be a pretty large call.

It had to be accessible by road and railroad because you were going to bring most of the supplies into the camp via railroad. You would move troops to the railroad, but you also needed to be able to get access by car, by bus and so forth. So it had to have enough fuel and water to support that large of a camp. And you had to have sufficient space nearby to where units could go out and train. And you needed a place that would be safe enough [that] you could fire artillery in it—because sometimes artillery doesn’t always go where you expect it to. So it had [to have] kind of a wide buffer zone on it.

These requirements soon narrowed the Lieutenant Colonels’ prospects to three areas. John McCown could see one of them from his perch on Cleaver Peak.

By late April, 1941, as John McCown was finishing his first year of law school at the University of Virginia, Walker and Hurdis were completing their investigations of sections of Idaho and Montana for a mountain camp. Adjacent to the western boundary of Yellowstone National Park, they found a site they deemed, as Captain John Jay would put it in his history of the mountain troops, “quite satisfactory.” Seventy-five miles northwest of the Tetons, two miles west of the Continental Divide and some sixteen miles west of the gateway community of West Yellowstone lies Henrys Lake, a rectangular-ish body of water in the middle of a wild, untrammeled landscape. Though the lake’s altitude, at 6,500 feet, was lower than what they were looking for, it had just about everything else on Hurdis and Walker’s checklist.

The lake was located in Idaho’s Targhee National Forest, which made negotiations easier and cheaper than they would have been with private landowners. Both a highway and railroad were already in place. The lake itself, while shallow, is four miles long and two miles across, providing ample water for the encampment’s 1 to 1 1/2 million gallons per day needs. The area’s real draw, however, were the mountains, the snow, and the cold.

West Yellowstone holds the all-time lowest recorded temperature for any residential community in the contiguous United States at −66 °F. Behind the lake, to the northeast, rise the Henry’s Lake Mountains, which culminate in five summits higher than 10,000 feet. North of that lies the Southern Madison Range, with nine peaks above 10,000 feet and four higher than 11,000. The Red Rock Mountains lie just to the southwest. And from November until April, all of it is covered in deep blankets of snow.

Convinced they’d found their site, Walker and Hurdis relayed the news back to DC, and construction of the 35,000-person West Yellowstone Winter Training Camp, as the Army base was to be called, was soon underway.

Had it continued, the mountain troops would have trained in the heart of majestic surroundings. The Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, within which Henrys Lake resides, is the largest intact temperate ecosystem in the world. Sweeping vistas, rolling grasslands, and picturesque mountains etch themselves against some of the clearest, cleanest air in North America. Springs dot the lake’s shoreline, which lies within a rolling, grassy basin. Grizzly bears, elk, deer and bighorn sheep roam the adjacent forests. The Henrys Fork, a tributary of the Snake River, flows from its southern end, providing blue ribbon fishing. Wetlands at its western and eastern ends serve as breeding grounds for numerous species of birds, including white pelicans, cormorants, great blue heron, bald eagles… and trumpeter swans.

As suitable as the area might have been for an encampment, it would have irrevocably altered a gem of an American landscape. It is perhaps fitting, then, that it was saved by the swan.

On December 6, 1941, the day before Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, the National Parks Association’s Executive Secretary, Edward Ballard, sent out a letter to its members. “Dear Conservationists,” the letter began. “The Trumpeter Swan is safe from disturbance by the threatened artillery range around Henry[s] Lake …. [T]he Army has abandoned its year-old plan for this development.”

“Last year,” Ballard continued, “the Forest Service sent a list of fifteen possible training areas to the War Department. From these the Henry[s] Lake site was selected for the proposed development, without formal request for its release. When the true situation was discovered early in the fall, the Interior Department made a serious study of the proposal. Behind-the-scenes efforts of several organizations … have helped to demonstrate that national defense needs can be reconciled with national conservation policies.”

Said behind-the-scenes efforts included the advocacy of one Frederic A. Delano, a railroad muckety-muck and vice chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Delano had been awarded France’s Legion of Honor and the US Distinguished Service Medal for his service during World War I. He had also invented and patented a one-way window glass, was part of the League of Nation’s International Commission on opium production and served as a member of the Smithsonian Institution Board of Regents. But his most important attribute was, at least in this case, the fact that he was President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s uncle. And he’d pointed out that an encampment of 35,000 soldiers would pose an existential threat to the world’s remaining 200 trumpeter swans that used the Henrys Lake area as their breeding grounds.

Delano’s efforts forced the Army to abandon its construction, which, Ballard argued in the letter, would have posed a “danger to the sanctity of Yellowstone Park itself…,” as the troops “would have used Yellowstone Park for maneuvers.” Presumably, they could have used the Tetons for their training as well, as they lay less than an hour and a half’s drive away.

Their primary plans scuttled, Colonels Hurdis and Walker turned their attentions south, to the high country of the Colorado Rockies.

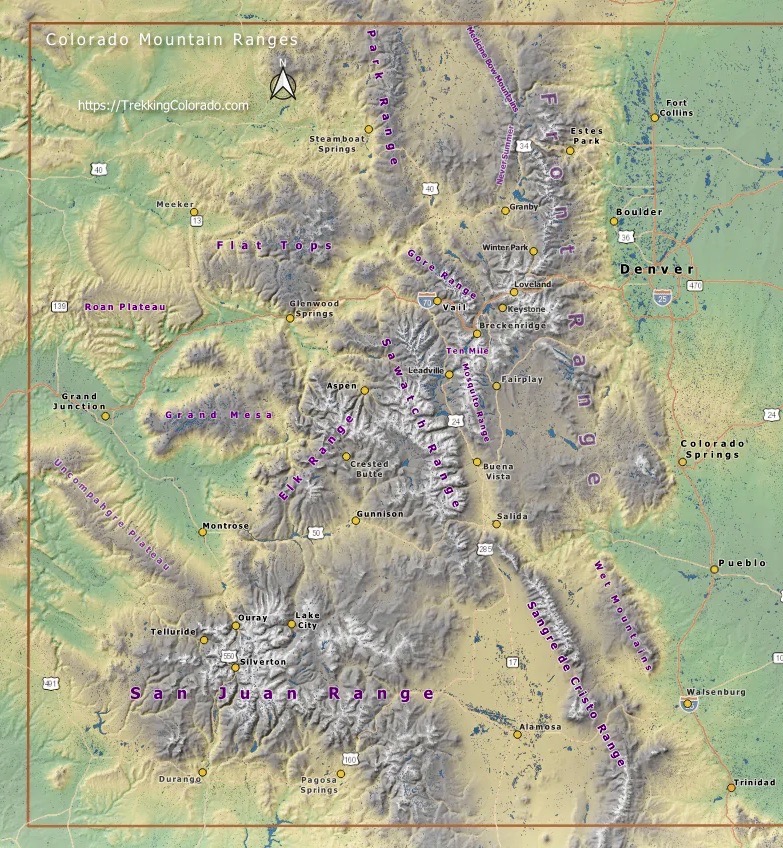

Seen from space, the Rocky Mountains stretch for more than 3,000 miles from the northernmost part of British Columbia to New Mexico, a jagged, continuous wave of summits, ridges and valleys that look as if they’re about to crash against the North American flatlands. In surfing, the part of the wave that holds the most power and energy is the steep, unbroken portion just in front of the curl. This section is called the face, and it is where, hydraulically speaking, most of the action can be found. Zoom in closer on the wave of the Rocky Mountains and you find its face centered in Colorado.

Colorado’s mountains, which occupy roughly the western half of the state, consist of eight distinct ranges. The longest and easternmost of the bunch is the Front Range, which stretches from the Wyoming border 180 miles south to Pueblo; its most famous mountain, the flat-topped Longs Peak, presides over all other summits in Rocky Mountain National Park at 14,259 feet high. The largest range, the San Juan Range, is a sprawling collection of peaks and valleys in the southwestern corner of the state that encompasses the towns of Telluride, Ouray and Silverton. In the center of the state, the Sawatch Range extends southeastward for 100 miles from the Eagle River to the little town of Saguache. It contains fifteen peaks higher than 14,000 feet, including mounts Elbert, Massive, and Harvard, Colorado’s three highest mountains. To its west lies the Elk Range, with the small cities of Aspen at its northeastern end, Crested Butte in its middle and Gunnison to the south. To its east lies the Tenmile-Mosquito Range, a single range split, somewhat confusingly, by the Continental Divide: the Tenmile Range lies on its north side, the Mosquito Range on its south. North of the Tenmile-Mosquito Range and running for some 60 miles northwest-to-southeast sits the Gore Range, home to the modern-day resort town of Vail; Interstate 70 cuts across its southern flanks. These ranges are, quite literally, the roof of the Rockies: from Denver, elevation 5,280 feet, the mountains rise nearly two miles to their highest points. Fifty-eight of them, commonly referred to as the “14ers,” are higher than 14,000 feet.

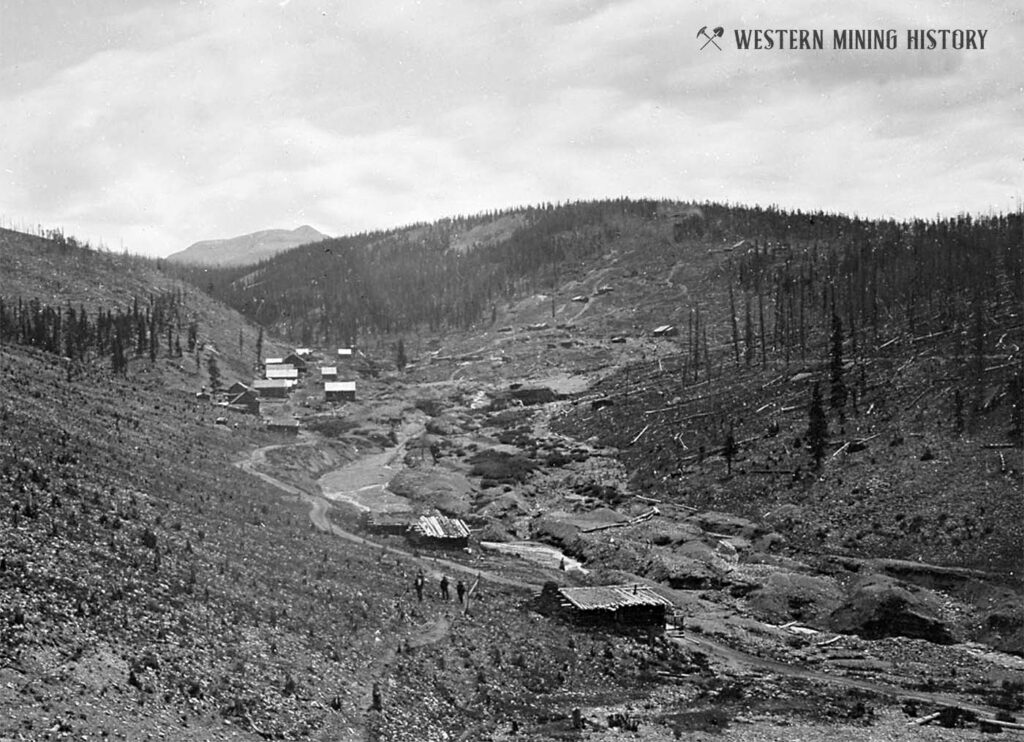

The lieutenant colonels’ search played out a bit like Goldilocks and the three bears. First up was Aspen, which had been languishing in what the locals called “The Quiet Years” since the silver boom had gone bust in 1893. Of the 12,000 people, six newspapers, two theaters, one opera house, and small brothel district that the town had harbored at the height of the boom, only the opera house and 777 resourceful, winter-hardened locals remained by 1940.

The Aspen area had sufficient flat ground for an encampment, but most of it was privately owned by ornery ranchers and gun-wielding claim holders, space was insufficient for military maneuvers and terrain suitable for proper climbing and skiing was too far away for efficient training. Hurdis and Walker then turned to the ghost town of Ashcroft. It, too, had been settled during the silver boom, and it had been, for one hot minute, vibrant enough to merit its own post office—but that was nearly thirty years in the past, and the only access that remained was via a Forest Service truck trail. The colonels investigated another abandoned mining site nearby, but if anything it proved even more remote.

But in the center of the state, midway between the small city of Leadville and the village of Minturn, in a long, broad, L-shaped basin sculpted by glaciers and encircled by the high summits of the Tenmile Range to the east and the even higher summits of the Sawatch Range to the west, they found a site that was just right: the Pando Valley.

Pando, as it would come to be known, ranks among the coldest and snowiest regions in the state, guaranteeing snow cover from November through May. At an elevation of 9,200 feet, it met the Army’s altitude requirements. It was secluded, sparsely populated (it had a railroad depot, but that’s about it), and was located on National Forest land, which simplified lease negotiations and lowered costs in the process. The Eagle River, wandered through the valley, providing enough water to meet an encampment’s needs. A scruffy outcropping on the east side of the valley provided terrain suitable for rock climbing, while the slopes above Tennessee Pass at the valley’s southern end were perfect for teaching soldiers to ski. Here’s Lance Blyth.

[Lance Blyth]

Pando was a train stop where you could put more coal, more water in these steam engines, and these were spread all along the railroad. Anyone who’s gone through the Vail Valley knows—you know Minturn, they know Eagle. These were all original train stops—and it looked good. It had a big wide valley floor. The road and railroad went through it and the road had just been built. Highway 24 had just been extended up from Highway 6 through the town of Minturn by Edward Vail, who was the chief highway engineer in Colorado, and he basically got this road built and it was probably the most expensive piece of roadway made at that time in North America. Just the bridge outside Redcliff alone was probably a pretty expensive undertaking. So you had the road, you had a railroad. The only downside was they felt that the nearby town of Leadville was maybe not the best social outlet.

General Marshall had gone around in the 1940, had basically gone in civilian clothes and gone to all these nearby towns and camps of the army he was mobilizing and realized that soldiers needed to get the heck out of camp—needed to go just have a hamburger or watch a movie, just get away, have some sort of social outlet. This is a citizen army. It is a conscript army and so you had to give a way to get them out. Leadville was an old mining town and your lieutenant colonels basically felt that it was a questionable social outlet, that it had relatively low morals as a mining town. And any mining historian will tell you, you did not make money by mining. You made money by mining the miners and that meant saloons, that meant prostitutes, opium dens, that sort of thing.

When discussing the Army’s deliberations about the Pando Valley, one cannot overlook the importance of Leadville, which lies 18 miles to the south, up and over Tennessee Pass. And when discussing Leadville, one cannot overlook the importance of the so-called “triple iniquities”—saloons, gambling and prostitution—that proliferated with Colorado’s development.

In 1848, the inadvertent discovery of gold in what would become California sparked the greatest mass migration in American history. Between 1849 and 1855, approximately 300,000 people, half of them foreign-born, flocked to the territory by both sea and land, transforming the west in the process. By the time the last of them were trickling in, California’s gold deposits were petering out.

The first Coloradoan traces of gold were discovered in a creek in present-day Arvada outside what is now Denver in 1850. In 1857, a much more significant gold deposit was discovered twenty miles to the south. The news quickly spread. Easterners who had been bankrupted by the Panic of 1857, the world’s first great economic disaster, saw the chance for financial redemption; Californian prospectors who had been frustrated by diminishing returns began looking east. A second gold rush was on.

By the spring of 1859, newspapers from St. Louis to Kansas City were reporting the passage of as many as 100 wagon teams per day, headed for the fabled riches. Some 100,000 prospectors flooded the region between 1858 and 1860, establishing towns along the Front Range—Denver, Golden, Boulder, Colorado Springs—as they arrived. It was a surge so powerful, it sparked the creation of the Colorado Territory the following year.

Most of the prospectors were transient, living out of their wagons or tents. As they ventured deeper into the mountains, they and their entourages—savvy entrepreneurs intent on a slice of the pie—established shanty camps and rudimentary road networks they could use to transport equipment, provisions, and discoveries in and out of the valleys on horse-drawn wagons. Settlements like Idaho Springs and Georgetown in the Front Range mountains became towns almost overnight as people arrived by the thousands in search of the latest golden rumors.

In the spring of 1860, gold was discovered in California Gulch, a mile east of what would later become Leadville, between the 14,000-foot summits of the Sawatch and Mosquito ranges. By the end of that summer, the ensuing camp, named Oro City, had yielded $2 million in gold and grown to a population of 10,000. Similar narratives unfolded across the region, displacing the Utes, Navajo, Shoshone, and other tribes who had used the valleys as summer hunting grounds for millennia in the process.

The prospectors engaged in placer mining, swirling sediment-filled water with a pan or sluice box so that the sand or gravel spilled out and the heavier gold nuggets stayed behind. By the time Colorado achieved statehood in 1876, most of the placer gold deposits were gone. Oro City’s population dropped to less than four hundred by 1865; two years later, the settlement was practically deserted. “Humbug mania” swept the region, and frustrated prospectors, as well as the service sector they’d inspired, became known as “go-backers” as they headed home.

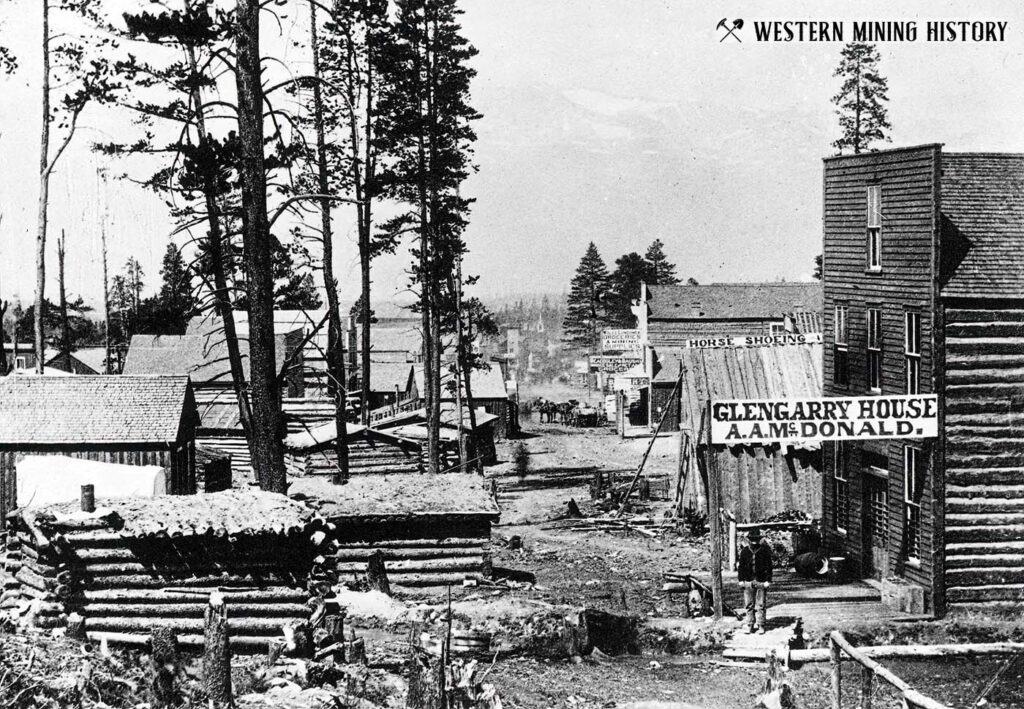

They left behind the infrastructural foundations of Colorado’s future: towns, buildings, roads, and railroads, all intertwined into knotted threads that linked remote valleys over mountain passes. The population ebb, however, didn’t last long. The area around Oro City, a forested plateau at nearly 10,200 feet, was covered in a heavy, black sand that had proven difficult to separate from placer gold. In 1877, prospectors discovered that the sand contained 15 ounces of silver per ton. The following year, Oro City became Leadville, the highest incorporated municipality in the country. By 1879, the city boasted 791 establishments, including 120 saloons, 19 beer halls, 115 gambling houses, 35 houses of prostitution, and 4 dance houses. The 1880 census recorded 14,809 people living within the city limits. Including the shanty towns that surrounded the city, Leadville’s population was closer to 30,000, second in the state only to Denver. The Tabor Opera House in downtown Leadville, constructed in 100 days by the local silver magnate Horace Tabor, was soon billed as “the finest theater between St. Louis and San Francisco.” In 1882, when Oscar Wilde performed on its stage, he described Leadville as “the richest city in the world.”

The mining camps that emerged during the Colorado Gold Rush were lawless and rough, and those that followed during the Silver Boom weren’t much better. As the historian Darby Simmons noted, the earliest prospectors to arrive were “primarily young, unmarried men who left their occupations and homes seeking to strike it rich mining at one of the newly discovered lodes. Following quickly behind them were those who mined the miners. This group included lawyers, bondsmen, shopkeepers, smiths and grocers, all of whom sought to exploit the needs of the camps and their male populations which seemed to have sprung up overnight. They could not, however, fill one of the town’s most pressing needs, the company of women.”

That role was filled primarily by prostitutes—the topic of Simmons’ honors thesis, Labor of Love: Prostitutes and Civic Engagement in Leadville, Colorado, 1870 – 1915. “The ratio of men to women in Colorado in 1860 was sixteen to one,” Simmons observed, “and in the California Gulch near Leadville there were only 36 women living in the midst of 2,000 men.” As it would in mining settlements throughout the Colorado Rockies, the profession played an outsize role in Leadville’s development.

As Colorado’s prosperity and population grew, the state sought to rein in the free-for-all by restricting both gambling and prostitution. Vice was woven into the fabric of mining towns like Leadville, but they had little choice but to comply, at least on paper. In 1881, the city of Leadville established a code of written laws directing its government to “suppress bawdy and disorderly houses, houses of ill-fame or assignation…, gaming and gambling houses, lotteries, and fraudulent devices and practices….”

Leadville enforced the new laws with a fine system. Those guilty of violations were required to pay fines ranging from five dollars to one hundred dollars. For the city’s prostitutes, who could make fifty cents or more per customer, the fines amounted to a business license. “On the last day of each month,” Simmons noted, “prostitutes, or the madams under whom they worked, were expected to report to the police station to pay a fine of five dollars [each]. Once the fine was paid, the women were free to go on their way and operate for the next thirty days without fear of interference by the authorities so long as they did not ply their practice on the streets, appear drunk, or engage in lewd behavior in public.”

From 1881 to 1915, revenue from saloon licenses, taxes, and fines collected from prostitution and gambling accounted for over half Leadville’s income. This revenue, which far surpassed that collected from any other taxable business in the city, underwrote many of its civil projects, including water supply, road upkeep, and payroll for the police and fire departments. “By the end of 1895,” Simmons wrote, “the city of Leadville had collected a total of $14,647 in fines from prostitution and gambling, more than doubling the amount [it had] collected … just four years prior.” The fine system would remain a major engine of Leadville’s development for the next thirty-five years.

In 1915, the Colorado state legislature passed a law that, among other things, declared all houses or buildings “used or resorted to as a public or private place of lewdness, assignation or prostitution” a nuisance. The so-called Nuisance Law marked prostitution’s “official” end, but in boom towns like Leadville, its practitioners simply went about their business more discreetly. “While the City Jail Register stopped listing prostitute’s fines,” Simmons wrote, “old timers in Leadville today pass down tales which suggest that the fine system …. continued to thrive for years afterward.” Indeed, the Pioneer Bar, a saloon and brothel, would remain in business until 1972. Gambling hadn’t gone anywhere either.

For Hurdis and Walker, this was a problem.

Much as the lust for gold and silver had created settlements of thousands almost overnight, the Army’s proposed encampment would develop an instant mountain town of 15,000 men, and they would need social outlets. Denver, population 322,000 in 1940, was 150 miles away. While only a tenth Denver’s size, Colorado Springs was equally distant. Leadville was only a hop, skip and a jump over Tennessee Pass, but a disproportionate number of its 5,000 inhabitants were engaged in professions that could undermine soldierly decorum. As the lieutenant colonels’ report would later note, that fact rendered Leadville unsuitable “as a recreation center for military personnel.”

Without access to Leadville, an army base in the Pando Valley would leave soldiers in a state of pronounced social isolation. That said, if one were looking for mountains, well, Pando had that in spades.

Lou Dawson is among North America’s best-known ski mountaineers. The founder and publisher emeritus of the backcountry ski blog WildSnow.com, and the author of the recent autobiography, Avalanche Dreams, Dawson was a top rock and ice climber of the 1970s, and, in 1991, he became the first person to ski all of Colorado’s 14ers. More important for our story, he lives in the Roaring Fork Valley, just over the Sawatch Mountains from Pando, and he knows the terrain around the Pando Valley like the back of his hand. Here’s how he describes it.

[Lou Dawson]

This really was high altitude—or is high altitude—exacerbated by what is actually a dry climate. They say Colorado would be a high desert if it wasn’t for the snowpack accumulating over the winter and feeding the aquifers throughout the spring and summer. 9,200 feet, that’s where you’re transitioning from a deciduous forest to conifers and just above there, at about around 11,500 feet, you reach timberline. And then things in the winter are just a barren windswept landscape that’s pretty harsh—a lot of wind. And the temperatures aren’t arctic like you’d think of them in Alaska. But in the winter you’re gonna get days that are consistently below freezing and then at night it clears up often and you get the radiation cooling to the sky. And nighttime is when you can get your consistently low temperatures around single digits down, say, to 10, 20, below zero during the colder parts of the winter, such as December.

In terms of terrain, if you were looking for mountain terrain, there’s no shortage. If you go five miles to about the southeast, you have the Homestake Ridge, which is a series of mid-height, 13,000 foot peaks. And if you continue about 20 miles south southeast, you have two of the highest peaks in Colorado, which are Mount Massive at 14,427 feet and Mount Elbert, the highest peak in Colorado at 14,440 feet. And what that means overall in terms of the terrain is you’re in some of the highest ground in Colorado. As soon as you strike out, you’re encountering elevations that are higher than you would ever have to deal with in Europe, for example.

And then if you go east, you encounter a vast area of kind of lower altitude terrain around timberline a little bit. Below that is kind of what you could loosely term foothills. But those foothills lead up to another range called the Tenmile Range, which again is, gets up there into the high twelves and stab into 13,000 [feet]. So essentially what you have is you can close your eyes and point, and no matter where you go in that area, you’re going to hit something challenging in terms of mountain conditions, especially during winter seasons. Now, let’s be clear that this isn’t the cliff walls type of terrain that you would climb, say in the high Alps or in other parts of Colorado, such as Longs Peak and Rocky Mountain National Park. Instead, it’s where you would have to practice skills that were more involved with how fit you were and how able you were to endure the hardship of just plain slogging through the terrain for miles and miles to get to these things. In fact, you could actually call most of what you do around this area advanced hiking.

While “advanced hiking terrain” might not sound that impressive, the mountains around Camp Hale would come to prove exactly the sort of landscape the troops needed for their training—particularly in winter.

In June 1941, as John McCown and Ed McNeill were embarking on their expedition to British Columbia’s Coast Range and Bob Bates and Walter Wood Jr. were preparing to explore the St. Elias Range on behalf of the Army, Lieutenant Colonels Hurdis and Walker reported back with their findings, reservations and all, to the War Department. Soon, a delegation of officers and engineers traveled out for further investigation. As John Jay noted in his history, they, too, found Pando up to snuff.

“The valley floor was large enough for a triangular division and formed a natural bowl, sheltered from wintry blasts by 14,000-foot mountains on all sides,” they observed. “The Eagle River and its branches were available for pure water…. U. S. Highway 24, an all-winter road, served the camp site…. Very few railway spurs needed to be built. An 110,000-volt power line was available. No gas was nearby, but coal could be had at Newcastle, 90 miles away on the railroad. Several ranges suitable to the employment of mountain artillery could also be developed, and large cleared areas were available for ski courses.”

They also agreed on the problems, particularly as it related to Leadville’s triple iniquities. “To solve this,” Jay noted, “the board suggested that pressure be brought to bear on local civil authorities to clean up the town….” They furthermore recommended that “special furlough trains be run by the railroad to Denver and Colorado Springs….” On an optimistic note, they added that the hunting and fishing around Pando were both quite good.

The reports seemed to settle the matter. Pando it was. The only dissenting vote was cast, as our advisory board member Chris Juergens points out, by the Engineers.

[Chris Juergens]

We just opened that new exhibit about the 10th Mountain Division at our museum, and there was some temptation when we were writing the labels. You know, editors kept wanting to weigh in: “Oh, why don’t you call it, ‘Colorado’s the perfect site for this camp?'” And that is not in fact what the 8th Corps report says in 1941. Pando Valley is considered “the most suitable site for such an installation,” but it certainly wasn’t the perfect site.

So some of the things that it had going for, we already mentioned: the accessibility by rail and by highway. It had the other requirements. The Army was looking for heavy snowfall [and] slopes suitable for skiing, including slopes that had already been cleared for various lumber activities as well as steep cliff faces for climbing and that sort of thing. But the balley needed to be manipulated quite a bit for the Army to actually prepare that installation.

So it’s not as if this was a ready made place for them. I mean there were still plenty of challenges left even though Pando Valley was the most suitable.

So it’s really in June 1941 when they get the mandate to start looking at these sites and they move pretty quickly considering that they get this order in early June to start looking at Pando Valley. Within 10 days, they’ve interviewed local forestry officials, they’ve met with the railroad, they’ve met with locals in the mountains. They understand that time is of the essence here because of the wintry conditions that do make Pando Valley so appealing for this kind of training. Those same conditions also make construction a nightmare, and so they’re really cognizant of the seasons up there and of the timeline that they would have to pursue—this really aggressive timeline to get this installation up and running in time before the snows roll in and basically grind it all to a halt.

The engineers were not just skeptical; they turned their reservations into a full-on buzzkill. “The Pando, Colorado site is found NOT well-suited from an engineering and construction viewpoint for a cantonment of thirty thousand men,” they roared (though, to be fair, they conceded that 15,000 men might be squeezed into the valley in a pinch). “[W]hile land costs are extremely low,” they continued, “in all other aspects this site appears to be unsatisfactory. The water supply is uncertain and the sewage disposal may cause difficulties. The cantonment is small and hemmed in on all sides so that there is no room for expansion. Access to the training area is limited . . . and construction costs will be higher for northern climates…. [T]his office,” their report concluded, ”is not responsible for the selection of … [Pando] for a camp.”

Well, shit. Leave it to the engineers to let a few small technicalities get in the way of a perfectly good encampment.

At this point in our story, dear listener, it should be pointed out that the world was pretty much on fire. Germany had been blitzkrieging its way through Europe like a sociopathic bully murdering sixth-graders for their lunch money. Earlier that winter, the Nazis had begun rounding up Polish Jews for transfer to the Warsaw Ghetto, where 10,000 would be intentionally starved to death between January and June alone. Great Britain had lost more than 50,000 civilians and a million homes to the German air campaign that would come to be known as the Battle of Britain. Hitler was days away from launching his invasion of Russia and initiating the mass execution of Russian Jews.

Fast forward five months to November 15, 1941. As John McCown was, rather begrudgingly, pursuing his law studies at the university of virginia and the 87th was assembling at Ft. Lewis under the command of Colonel Onslow Rolfe, the Pando matter still lingered. By January, Pearl Harbor had plunged the US into war, John had dropped out of law school to join the 87th, Hitler had completed his plans for the mass murder of some 11 million Jews across Europe, and Colonel Rolfe remained a red-headed cavalryman with a mountain problem. The Swiss mountaineer Peter Gabriel had joined two thousand other skiers and climbers at Ft. Lewis, but without a proper mountain camp, there was little he could do to teach the troops to ski. To address the issue, Rolfe had been forced to negotiate a short-term lease for the Paradise and Tatoosh Lodges on Mt. Rainier’s southern flanks. The need for a permanent encampment was abundantly clear—but the Pando issue remained unresolved.

What the mountain troops needed at this point was a hero. It certainly wasn’t going to be General Leslie McNair, the mountain-doubting architect of General Marshall’s army. While world events had convinced him to approve the 87th as a test force, he was still opposed to the concept of specialization in principle, a passive-aggressive resistance that would simmer within the War Department for more than three years. If the mountain troops were going to get a camp, it would be up to their leader to secure it.

On February 6, 1942, as John McCown was finishing up his basic training in California’s Camp Roberts and Peter Gabriel and John Jay were preparing to take up residence in Paradise with the rest of the 87th, Rolfe made the journey east to see the Pando Valley for himself. His arrival was greeted by two feet of snow. Now this, he decided, was a place he could get behind.

Over the course of the next five days, Rolfe explored Pando’s nooks and crannies with an eye to what he knew his troops would need. To address the lack of social outlets, he proposed building playing fields as well as a special indoor arena the troops could use as a recreational center. Recognizing that a valley colder than a barefoot skier’s toes would wreak havoc on morale, he recommended barracks be insulated to 20 below. He knew the future division would need supply rooms to house its specialized gear; it would also need stables for its 5,000 mules. He noted his recommendations accordingly. Though he’d only been in command of the mountain troops for three short months, that still made him the Army’s ranking officer when it came to mountain warfare, and his recommendations did the trick.

“This afternoon,” Leadville’s newspaper reported on February 27, 1942, “The Herald Democrat received the following telegram from US Senator Edwin C. Johnson who is in Washington: ‘Have succeeded in getting Pando for winter training back in (the) picture. Prospects (for) its selection are good.”

The news came at a time of renewal for the high-altitude settlement. War is good for business, and, as European belligerents had begun preparing for battle, the Molybdenum Mine in Climax, fourteen miles to Leadville’s north, had begun ramping up production of the metal, which was used to strengthen steel and other alloys. The Climax mine was located in Lake County, and taxes from its production flowed to Leadville, the county seat. As other mines that had gone idle between the wars resumed production, the town’s atmospheric boom-bust cycle was back on.

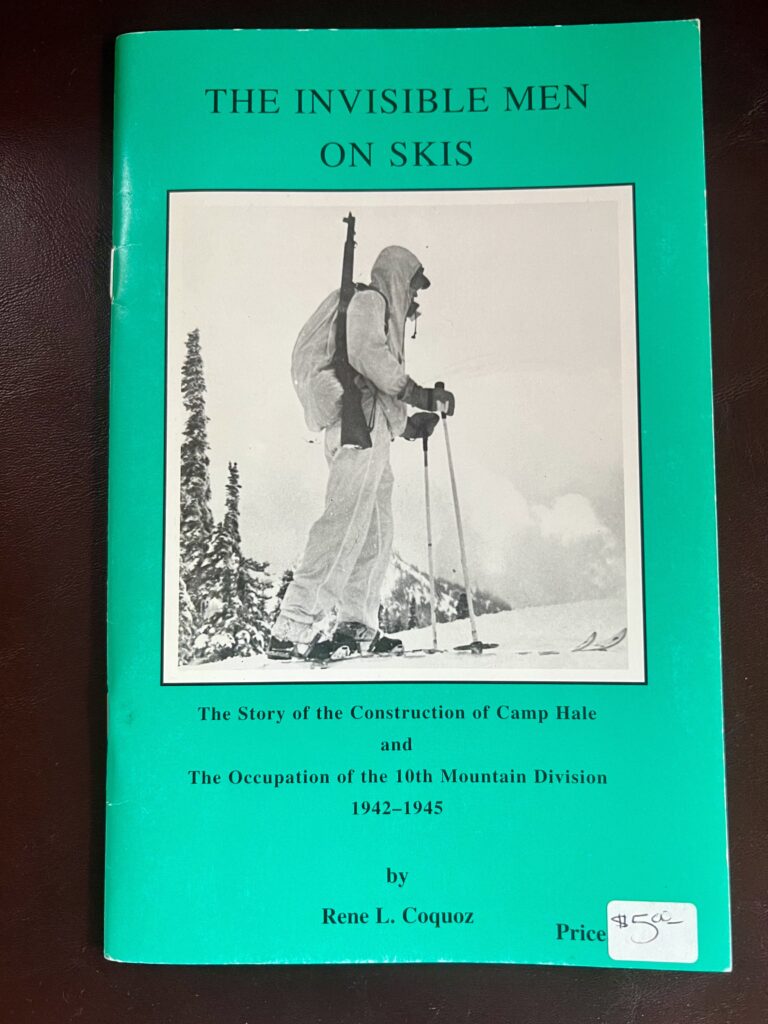

In 1970, Leadville historian Rene Coquoz published a 32-page pamphlet entitled “The Invisible Men on Skis.” The pamphlet, which you too can purchase for the eminently reasonable sum of $5 from the local souvenir shop, documents the impact the encampment and its construction had on the town. According to Coquoz, on March 31, 1942, the Herald Democrat received two telegrams from Colorado politicians eager to take credit for something neither had made happen. Both announced the same thing: they had just received official notice from the War Department that construction of a “five-million dollar cantonment” at Pando had been approved.

Coquoz’s pamphlet includes another interesting bit of history. A year earlier, both City and County attorneys had been directed by the feds to establish a full-time health unit. The unit, which was to be staffed by three to five nurses and overseen by Army physicians, would be responsible for child welfare, water and milk sanitation as well as “other health conditions,” which Coquoz defined simply as “bars, restaurants etc.” Anyone with the slightest familiarity with Leadville’s history understood that the feds wanted Leadville to take care of its triple iniquities as well.

When the US Government tells you to clean up your act, you comply, which is what the City and County Commissioners agreed to do at a City council meeting on June 19, 1941. But agreeing to do something and actually getting it done are two different matters.

In the days of the gold and silver booms, railroad workers engaged with prostitutes left red lanterns outside the doors so they could be roused when it was time to get back to work. The collective glow on busy nights gave birth, as it were, to the term “red-light district.” Leadville’s had existed since the city’s inception. Now, it was ordered closed, “and the brilliant lights of the so-called ‘cribs’,” as Coquoz put it, went dark. “Some of the prostitutes simply moved to other parts of the city,” he continued. Lake County’s police force, which consisted of a City Marshal, a night Police Captain, an officer, and a two-person sheriff department, dutifully tracked their whereabouts. “Known prostitutes who remained in the city and county were compelled to report at three-week intervals for an examination by the city and county physician,” Coquoz observed. Other vices were curtailed as well. “The lid on gambling was tightly closed and heavy fines were imposed on anyone arrested during a gambling raid.”

While Leadville scrambled to get its house in order, the feds prepared to build. In the leadup to war, President Roosevelt had spearheaded a massive military expansion that included restructuring how bases were constructed. Remember the Quartermaster Corps, the Army unit Bob Bates and Bill House had joined at the start of the war? Their mandate was to develop gear, clothing, and food for the mountain troops. But the Quartermaster Corps was responsible for much more—it oversaw the development, testing, procurement, and production of every item in the Army’s arsenal—including the development of military bases. It was too much. Beginning in late 1940, those duties were transferred to the Corps of Engineers. Within the year, real estate acquisition, construction, and maintenance for a wide array of domestic Army facilities, including training camps, air bases, and munitions plants, fell under the Corps of Engineers’ umbrella.

By 1942, military base construction in the US had reached unprecedented levels. Expenditures in July 1942 alone surpassed the total spending from 1920 to 1938. Rapidly built and bustling with activity, these bases became significant economic hubs for adjacent communities.

As the Corps of Engineers oversaw the construction of bases in Arkansas, Missouri, Alabama, Florida, Virginia, Texas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Georgia and Tennessee, local economies prospered. By year’s end, the Army had built out enough new bases to house nearly four and a half million soldiers—and the influx of federal funds, coupled with the arrival of thousands of civilian employees to meet the needs of the burgeoning military sites, transformed the economic and social fabric of adjacent communities.

How did the Corps of Engineers build so many new bases across the country in such a short period of time? By adopting the same cookie-cutter approach General McNair applied to all aspects of the Army’s expansion. Everything was the same: the barracks, the training lanes, the recreation facilities, the mess halls, the roofs, the walls, the windows, the doors. You could walk into Camp Livingston in Louisiana, Camp Shelby in Mississippi, Camp Gordon in Georgia, or Fort Campbell in Tennessee and not be able to tell the difference. That was the point. The only way General McNair was going to be able to build an army big enough to defeat Hitler was to borrow directly from Henry Ford’s assembly line approach.

These bases had something else in common as well: location. They were all in the south, where land was cheap, the construction season was long, and the relatively mild climate allowed for year-round training.

The land in the Pando Valley might have been cheap, but the long winter that made it ideal for cold weather training also made construction a complicated and very expensive race against time. It necessitated tweaks to the cookie cutter approach as well: buildings had to be constructed to withstand snow and cold, coal-fired stoves had to be installed for additional heat, supply rooms had to be built for skis and mountaineering equipment and stables had to be designed to accommodate the mules. All of it added up to yet one more instance of specialization to chafe General McNair’s backside.

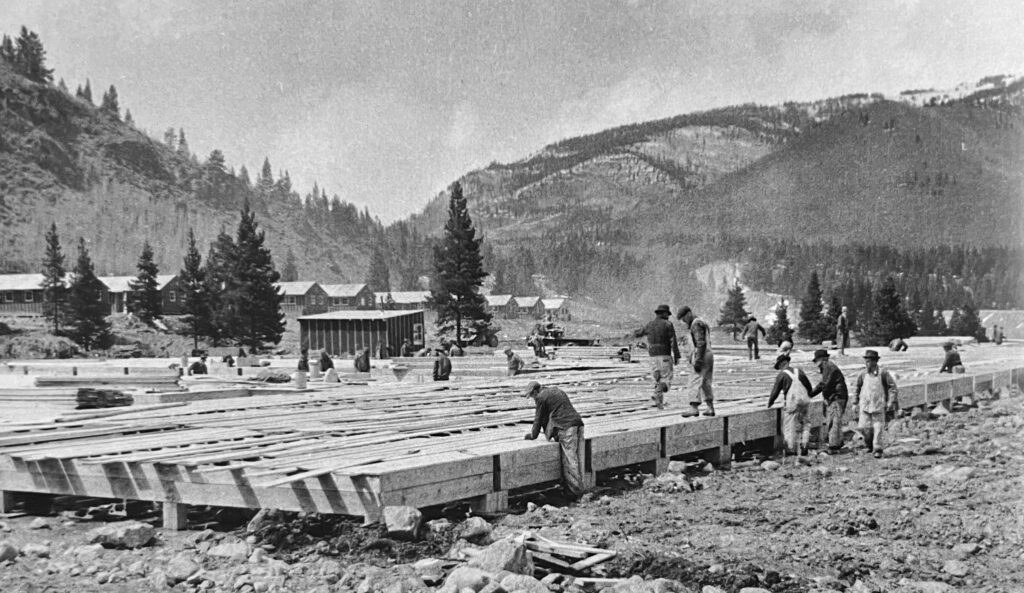

How does one build a military base at 9,200 feet for 15,000 soldiers, 5,000 mules, and 200 dogs before winter intervenes? For one, you do it quickly: by early April, as John McCown was joining the 87th at Ft. Lewis, the next season’s snows were already less than seven months away.

Planning for the camp began on April 3. Four days later, the War Department negotiated a contract with Black & Veatch, consulting engineers out of Kansas City, and Platt Rogers, Incorporated, contractor of Pueblo, Colorado, for the “design, professional supervision, and construction”of everything the camp would need. On April 10, construction began in earnest.

As the bulldozers began arriving in the Pando Valley, a crucial debate was unfolding in Washington.

Even if the engineers and contractors were able to complete their historic construction project in time for winter, the question of who would occupy the camp remained unresolved. John McCown, Peter Gabriel, John Jay and the rest of the 1st Battalion of the 87th Mountain Infantry were a test force, and one comprised of a mere 2,000 soldiers at that. Pando was being developed to house a full mountain division of 15,000 men. As engineers began removing two hundred beavers from the ice-filled Eagle River and clearing 17 acres of willows from the snow-covered valley floor, Generals McNair and Marshall were furiously debating how to populate the camp.

“It seemed to these officers,” Jay observed, “that to activate a division in December in the heart of the Rockies, and start basic training with raw recruits at that altitude and season was not a wise move.” Instead, McNair proposed forming a new unit—soon to be named the Mountain Training Center—at the newly completed Camp Carson, just south of Colorado Springs. With recruitment support from the National Ski Patrol System, the 87th would expand to a regiment of 4,000 men at Ft. Lewis before moving to Pando in the fall. To meet the need for mules, the War Department planned to relocate the 4th Cavalry from Ft. Meade, South Dakota, to Pando as well. Under Colonel Rolfe and the Mountain Training Center’s command, the entire operation would gradually ramp up over the winter as a test force—a more advanced version of what Rolfe had already organized at Ft. Lewis. A full Mountain Division would be activated in the spring from this foundation. While the plan wasn’t foolproof, it gave the War Department the flexibility it needed to finalize details as Pando was being built.

The crews in Pando, meanwhile, had their work cut out for them. The Eagle River not only meandered through the valley; it left much of it a swampy mess. To straighten it, engineers dug a single channel through the valley’s center, scraped 2,000,000 cubic yards of earth from the adjacent hillsides and used it to level the valley floor.

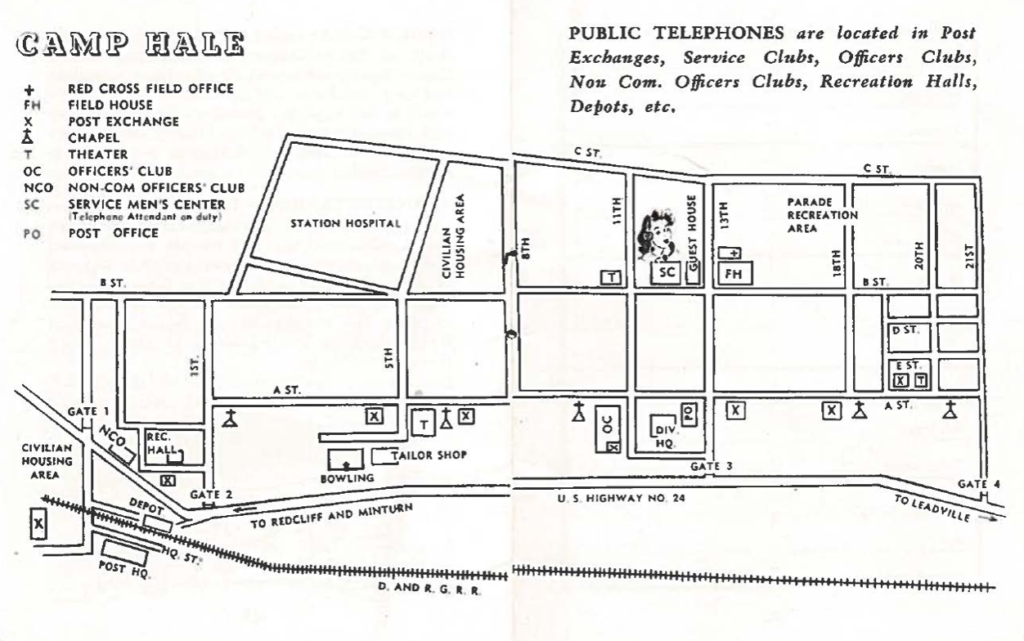

As Lance Blythe noted, Highway 24 had been shortened and straightened at a cost of nearly $400,000 – the most expensive road project in state history. Now, a road network was laid out in the center of the valley in a grid pattern: A, B, C and D streets ran the valley’s length, while 21 numbered roads cut across its width. Space was marked out for exercise fields, a parade field, a bayonet course, a gas mask drill area, and rifle and pistol ranges. On May 1, as the 2nd Battalion of the 87th was activated at Fort Lewis, adding another 1,000 men to the regiment, foundations began going in. Just as the mining camps had sprung up almost overnight, a new boom was on in the Pando Valley.

Leadville had been told that the construction would double its population. The estimates would prove off by a factor of two. As Jeff Leich notes in his book, Tales of the 10th, the operative hiring philosophy for the project was “Hire everyone – then weed out the incompetents.“ Soon, workers “began arriving en masse,” as Leich put it, “in a caravan of cars.” Vehicles and trailers filled the roads leading into town as people came to work from every part of the country. Since Leadville had neither the rooms nor the houses to accommodate them, it began fixing up homes that had been abandoned during the last bust. People slept under trees and in their vehicles. Leadville’s miniscule police department found itself on call night and day. The town, which had had no patrol cars, added one. The City Council, which had historically met twice a month, began meeting once a week, and then multiple times per week as the need arose. Local stores were soon selling out of milk, bread, and eggs by 11 a.m.

In June, as the activation of the 3rd Battalion added another 1,000 men to the 87th and Peter Gabriel prepared to join Bates on a gear-testing expedition to Mount McKinley, the highest military encampment in American history continued to come together. To accommodate the overflow of workers, 87 barracks, a 603-trailer trailer camp and 12 mess halls were developed in the Pando Valley. Buildings, all painted a uniform white, began to rise: barracks designed to accommodate five dozen men, complete with built-in storage for skis and mountaineering equipment, alongside mess halls, stables, an officers’ club, a Service Club, a field house, a bowling alley, a Red Cross station—over 1,000 structures in total.

The encampment received its official designation on Flag Day, June 14. The Denver-raised, West Point educated Brigadier General Irving Hale had graduated with the highest score ever recorded at the academy. As an officer with the Colorado National Guard, he had earned a Silver Star during the Spanish-American War and later played a key role in organizing the Veterans of Foreign Wars. Now, in the shadow of Colorado’s highest mountains, his legacy received the tribute it deserved, as Camp Hale was named in his honor.