A version of this article appeared in the February 1998 issue of Rock & Ice and the book The Best of Rock & Ice: An Anthology.

—-

Bishkek: the ache of traveling knees, the smell of unwashed crotches, thin film of sweat in dried waves on our skin. An English show dubbed in Russian blares from the window of a cement-block apartment complex. Fetid water gurgles in shallow canals on the shoulders of the streets. Old women in flower-patterned dresses sell laundry soap and Fanta from rickety wooden tables while Ladas, the vehicle of the proletariat, fart foul exhaust into thin blue air. White mountains float against the haze. We have come to climb them. What we do not expect is the struggle at their base.

In Kyrgyzstan’s capital, as in all the former Soviet Union, communism is finished, ripped from the body politic by a violent and imprecise event called perestroika. Grandparents reel from it, unable to comprehend what it has done to their world. Their grandchildren will feel its effects for generations to come.

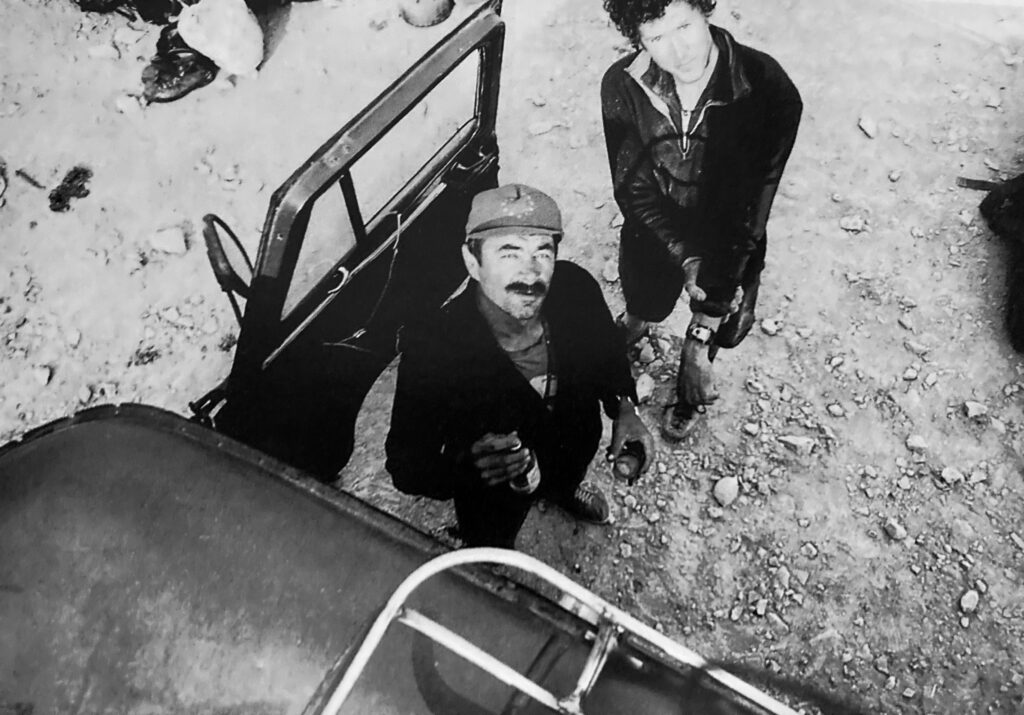

My climbing partner, Brady Van Matre, and I stay with Vladimir Komissarov, the president of the Kyrgyz Mountaineering Federation, in a disheveled, clean bungalow that serves as the offices for his guiding company. We drink vodka. Everyone always drinks vodka.

“Before perestroika,” Vladimir tells us, “there were thousands of climbers in Bishkek. Now there are very few. Before, all you had to do was show up at the alpine center for gear provided by the government and go off into the hills and climb. It was very easy. Now everyone worries about work; there are few people who can afford to climb anymore.”

Nearly 5,000 feet above Bishkek’s leafy streets lies a clutch of glaciers and stunning peaks that comprise the crown jewels of Ala Archa National Park. The park is as close to Bishkek as Rocky Mountain National Park is to Estes Park, and similarly blessed with climbing objectives, though the Kyrgyz park has far more ice than granite, its glaciers, both large and small, cradling 2,000-foot lines. Were they in the west, walls such as the 3,000-foot north face of Free Korea Peak would be world-famous. In Kyrgyzstan, they’re deserted.

Brady and I spend a week in the park and see six other people. It’s late in the season, and the weather is changing, growing colder; a day after our first climb, it snows half a foot in twelve hours. Is this why there are no climbers here? Maybe. But with a city of more than 600,000 people a mere six hours’ hike away, we have our doubts.

——

Brady is a Colorado climber, tall and lean and reserved, tight coils of brown curly hair hinting at the restless energy that has brought him halfway around the world to climb in the Switzerland of Asia. In the half-light of dawn we skittle across the Ak-Sai Glacier for our first objective, a 2,000-foot ice line that soars up to a crenelated ridge. I go first, trailing a rope and moving quickly, then slow as the surface crust becomes broken by sporadic patches of ice. Hundreds of feet up, a tumble of large granite blocks pokes out at the couloir. I size up the remaining distance and concentrate on my placements.

Ten feet from the boulders, the snow goes to hell: my tools plunge into depth hoar before finding purchase. Suddenly my tool hits a rock the size of my chest, and it sags away from the slope.

“Brady! I’m holding in a rock with my tool! Traverse right! Get out of the way!”

“Hold it in!” he yells. I can see him looking up at me beyond my heel, wide-eyed and frightened.

I hold the loose block with my axe until he is sheltered from sight, then gingerly relax. The block holds. I climb above it and angle toward an outcropping for an anchor. When Brady reaches the block, he taps it with his pick. lt rolls from its perch and tumbles down the mountain.

We rope up, and, with Brady in the lead, move onto the first real ice of the climb. When the ropes go tight we simul, the couloir singing up straight as sunshine, our tools sinking snugly two inches deep.

l am out of breath by the time I reach him. To our left, the ice surges through a vertical bulge.

“How’s the anchor?”

“All right. Decent ice.”

The ice is brittle here, and steeper than anything I’ve been on in the mountains. I sink a screw 15 feet out, then another at a block twenty feet higher while Brady mumbles words of encouragement from below. The ice is thin and hollow, melted out by hidden rocks that blunt my picks. Confidence recedes, then reappears as I set up an achor.

Brady goes next, getting in one screw 20 feet above me and another 80 feet above that. He disappears from sight, and I feed out the rope without a break for half an hour. When l start climbing, I find that his second screw was his last.

Aiiy! Calves burning, lungs cracking, l thunk-thunk my way up the couloir. The sun has burst over a corniced ridge; sweat percolates through skin, soaking polypro and GoreTex as I arrive to find Brady sitting comfortably on a golden granite bench. Sweat wets my scalp, mingles with my hair, drips down behind my glacier glasses.

“Nice lead,” I offer.

“What did you say the highest you’d been before was?”

“Thirteen seven-twenty. What are we at now?”

“Ten feet shy of that,” he says, holding out his watch.

The couloir rises along a rib of rock for another 200 feet, then flows around a gendarme in the middle. We have to climb left; a healthy serac caps the ridge crest to the right.

“All right. Give me a shot of water and I’ll get out of here.”

The line exits via a steep constriction that hugs the rock wall of the gendarme. I place a nut in a fissure and then it’s away, up into the ice as it narrows and gets steeper, picks sinking perfectly, angle kicking back, rock wall looming behind my head. Up, up, each placement bringing me that much closer to the two-foot gap at the top, until finally I am swinging awkwardly into névé and dragging my heaving body into bright sunshine and flat snow. The wind howls and whistles; I stand blinking in the bright glare, awed at the panorama of mountains before me. I throw down my tools, sling a flake and bring Brady up.

——

A few days later, we take dinner with Vladimir at a hole-in-the-wall restaurant 100 yards from his office on Panfilov Street. We drink char, the dark brown tea leaves congregating in swirling clumps at the bottoms of our glasses, while he questions us about our impressions of the Ala Archa. We tell him about the couloir.

Vladimir, who was born in Bishkek and has climbed in the Ala Archa all his life, squints his blue eyes in concentration.

“That route is new route,” he announces, sliding skewered pieces of mutton and raw onion past his mustache and into his mouth.

We whoop, high-five, inadvertently spit food onto the dirt floor. Impossible! How could that be—such an obvious ice route, and in mountains twenty-five miles from the nation’s capital? Something here is amiss, and we set to work trying to understand how such stunning peaks could be so free of climbers, how obvious lines could remain unclimbed, and how the rest of the world has not heard of these wild knotted mountains in the lost heart of Asia.

——

In 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev took over the reins of the Soviet Union and began the ambitious and unprecedented campaigns of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), he pitted his resources against the biggest bureaucratic monster in the world. For six years, he whittled away at its systemic flaws, encouraging movement toward democracy, private enterprise and self-will. In 1991, the monster thundered to the ground. The Soviet Union was dead.

In the west, Gorbachev was a hero. At home, he had destroyed a safety net that provided security to his people. The basic services upon which they had depended—medicine, education, housing, jobs—were gone. The money to fund the services had all been used up in the arms race with the West. What was left fell into corrupt hands. Honest people—people who had spent their lives paying into a system of communism—were told that the system was bankrupt, and that now they were on their own.

Vladimir and I eat again at a restaurant a block from Victory Square. I pepper him with questions, trying to understand what has become of his country, its people and its climbing.

Within the framework of communism, he tells me, alpinism played out along a party line. Money was available to the “trade unions” of the USSR for various pursuits, mountaineering among them. Climbers had to join a union, which gave them vouchers to attend mountaineering camps and equipped them with the necessary gear.

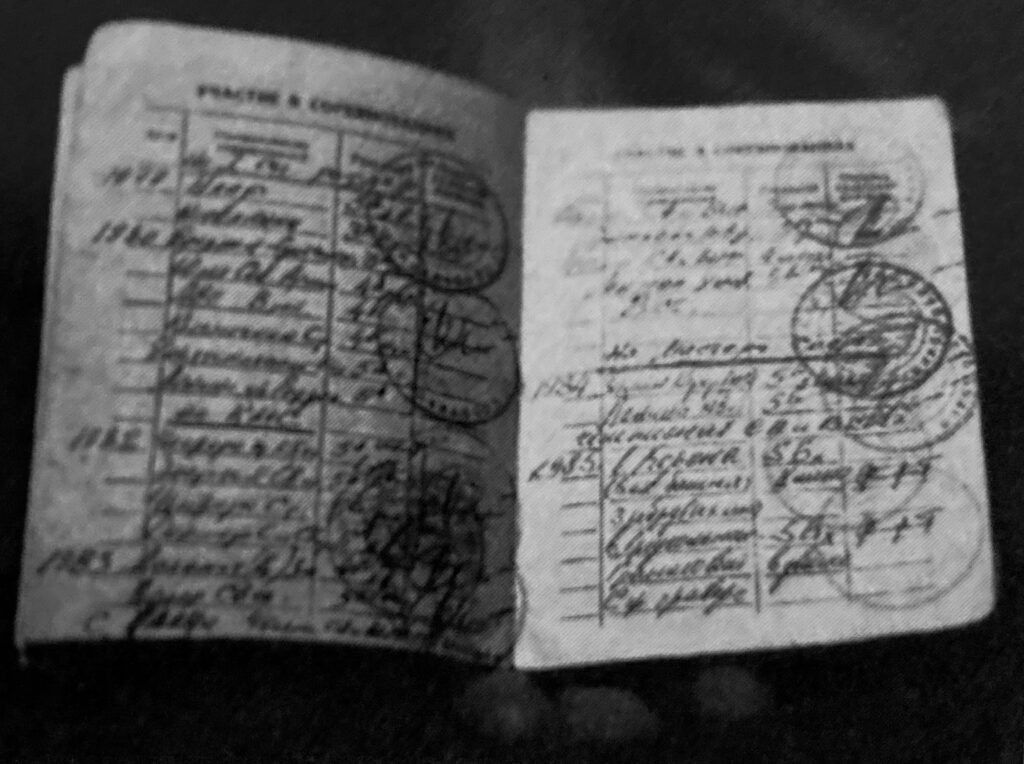

Every climber in the USSR had a Climber’s Book, into which was entered a complete history of his or her climbing, all validated by climbing officials. Climbs in the Soviet Union were assigned a grade. If a climber wished to climb a route of a certain grade, he or she had to receive permission for that route from the appropriate alpine authorities. In order to receive permission to climb, say, a 3b, a climber would have had to have had their Climber’s Book stamped with satisfactory performances on routes of 3A.

“But Vladimir,” I pause, trying to understand. “What about new routes? How could you explore new areas and new mountains if everything had to be pre-approved?”

“You had to make a proposal to the trade union,” he says, “detailing where the route would be, how hard you expected it to be, and showing qualifications that proved you could do it. Then, if you were given approval, you climbed—because, if you didn’t, for weather or any other reason, it went down in your book, you were demoted, and you had to start again at a lower level in order to regain your status.”

I ask if there were any climbers who refused to take part in the systems, who climbed independently, rebels in a lockstep world.

“Impossible,” Vladimir says. “To do that you had to have your own equipment, which meant you had to have your own money—and nobody had that kind of money. To climb, you had to climb with the trade unions—and to climb with the trade unions, you had to climb by the rules.”

I had read of climbing competitions within the former Soviet Union: speed ascents on the limestone walls of the Crimea and the soaring, 7000-meter peaks of the Pamir and Tien Shan, and new route competitions in the alpine peaks of the Caucasus and great granite walls of the Pamir Alai. Many Western climbers denigrated these competitions, and I, too, felt they ran counter to the spirit of climbing. Now, l began to see that competitions were an organic extension of a system where climb and climber—as with every other aspect of society—operated according to strict codes.

But this was the world before perestroika, and, just as the complete order of Soviet life disintegrated with Gorbachev’s historic moves, so, too, did the internal scaffolding of the alpine system that made climbing possible for Kyrgyzstan’s climbers.

——

A few days after our return to Bishkek, Brady and l hook up with Matthias Engelien, a young German climber with greasy hair, acne and a high lilting laugh we’d met during our week in the Ala Archa, and the three of us journey to the Karavshin region of the Pamir Alai. After a three-hour flight to Osh, Kyrgyzstan’s second biggest city, we hire a taxi to take us to the Tajik town of Vahrook. From there, we make the 50-kilometer approach into the Ak-Su Valley in two days.

Again, the wild, Patagonianesque formations that form the jagged walls of the Ak-Su Valley would be festooned with climbers in the west. Again, we have the place practically to ourselves.

A helicopter arrives two days after we do and disgorges a load of Brits. They’re on a guided mountain holiday with the legendary British climber Pat Littlejohn, and Komissarov has stashed our food and gear amidst their kit. The next day, Brady, Matthias and I climb a 1,000-foot granite pillar at the base of the magnificent Slessova Peak—six or seven pitches of moderate, fun cracks that vary from incipient to sphincter-tighteningly wide. Brady finds shiny new bolts adjacent to the cracks at the top of the first pitch. Higher, I get my head wedged in a womblike feature as I try to chimney when I should have thrutched. We make the top by late afternoon, and descend with gratitude for the convenience (if not the unnecessary placements) of the anchors.

The British tents spiral in an irregular circle around the mess tent. There are 12 clients and three guides. Two Kyrgyz men, Yuri and Agnar, quickly put together a comfortable hamlet that includes a shower, a privy (complete with an inexhaustible supply of toilet paper—the first we’ve seen in Kyrgyzstan), a cooking tent, a food tent, a deep fire pit and half the dead wood in the area to feed it. The group eats lavishly, three times a day. A woman named Ala works from five in the morning until ten or twelve at night to prepare their food. We quickly make her acquaintance.

Ala is petite, with fine red hair and rounded, slightly Kyrgyz eyes. The morning after our climb I ask her whether she is a climber.

“Oh, not now, not as much,” she says. “One time, yes. But since perestroika, I can only work.”

Ala is a doctor by training and profession, but the pay of roughly $20 a month is not enough to make ends meet. When she found an opportunity to work as an interpreter for a British company, she parted ways with medicine. She has a month off a year, and for two years in a row, she has gone to the mountains with Littlejohn, who pays her the equivalent of a doctor’s monthly salary every day.

I talk to Ala about her climbing.

“I was part of a team in Bishkek,” she says. “There were six of us, and we only climbed together. My job was to climb quickly, to never hold up the team. We climbed well—up to the 5b level. I jumared the pitches—I never led, but it was very fun. We were a good team. Every summer, we would climb two times together, for two weeks in May and two weeks in November, at the alpinist training camps. The trade union would give us permission to leave work for three weeks and pay 30 to 50 percent of the fees. Everyone went to the Ala Archa to climb. But after perestroika we stopped climbing: the trade unions were dissolved, so there was no equipment, and we all had to work too much to climb.”

“How has perestroika affected climbing in Bishkek?” I ask.

“Before perestroika there were many, many climbers—not less than a thousand. Not everyone who started in the camps continued climbing, of course: maybe 70 percent kept climbing, and of them 30 percent were serious climbers. But now there are maybe 20 or 30 climbers in Bishkek—no more.”

We attempt two more peaks in the Ak-Su and fail on both. During the days, the thundering granite walls keep the sunlight from the valley for all but a few hours; at night, their silhouettes block out the stars. We kill a sheep in basecamp; Vladimir skewers the meat on whittled branches, and the blood runs into our hands as we eat. We climb a final line, then drive a train of pack mules down the valley to Vahrook.

——

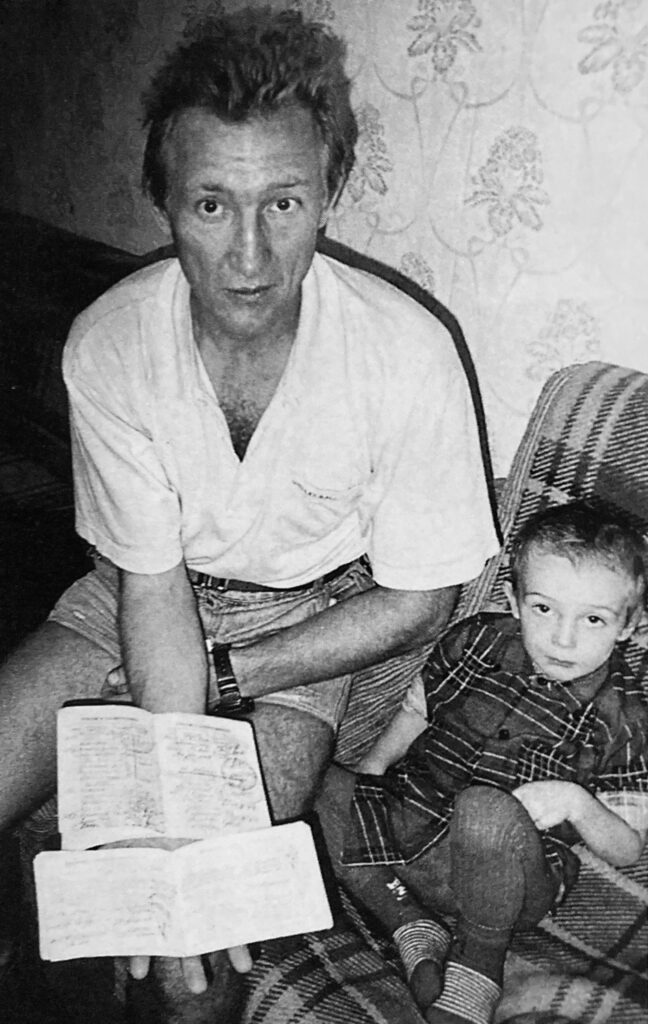

Back in Bishkek, I speak with Alexander Agaphonav, a Master of Sport, the highest level one could achieve in Soviet alpinism. He is 38, 5’ 8” and compact, with legs that ripple with tight muscles beneath torn and patched denim shorts worn thin over countless summers and innumerable climbs. His blond hair is spare, and his wide Russian face is punctuated by the lumped bridge of a nose broken long ago.

While a woman from a local trekking firm translates, I talk to him about climbing before and after perestroika.

“We had two kinds of climbers before perestroika,” he tells me, “one professional, the other who climbed as a lifestyle. The professionals were part of 16 teams in the former Soviet Union. Each team had eight members. Of these, four were masters of sport and four were apprentice masters. The masters were masters of six classes of climbing, for which there were competitions: rock class, for mountains not higher than 5000 meters; technical class, which was climbed regardless of height of mountains; ice class; high technical, on mountains higher than 6500 meters; traverse class; and winter class. Sometimes there were competitions between the two kinds of climbers in three different classifications: high peaks, middle peaks and low peaks. The winners became part of the professional teams.”

“The professional climbers received a salary from the state, though it wasn’t enough to live on, and the climbers had to find other ways to earn money. Meanwhile, you had to always train, always be in shape for the competitions, and you always had to take part in higher levels of competitions. It was a special kind of life, not a sport: you had to live to climb. lt was a very hard system to take part in.”

At his apartment, Alexander shows me his climber’s book. In it are recorded and duly stamped all the climbs of his career, from his earliest ascents in the Ural Mountains, where he had lived before perestroika, to his climbs as a Master.

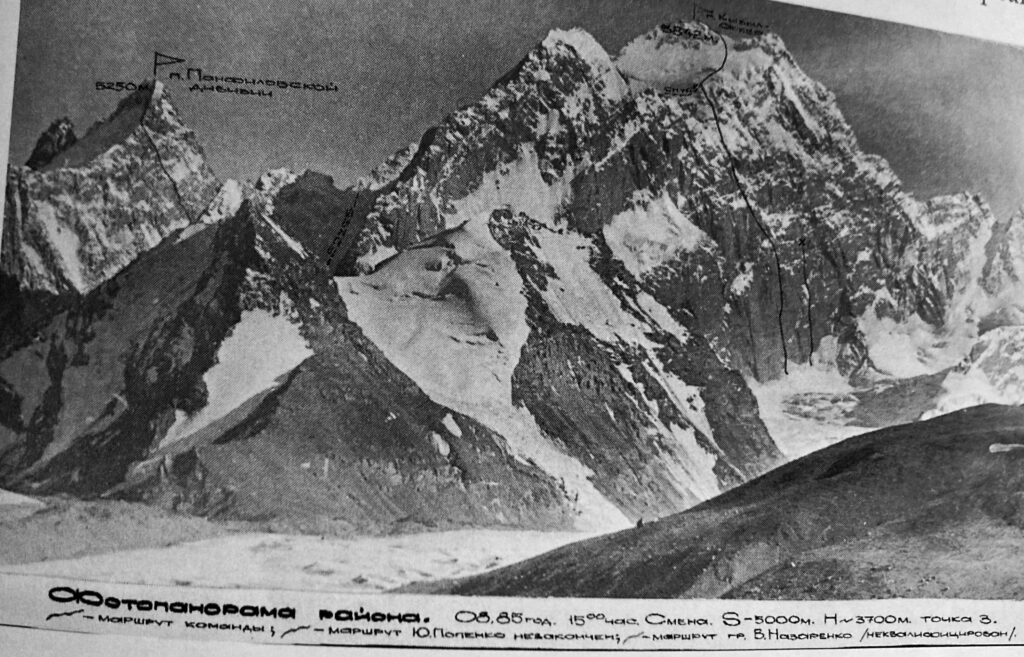

He pulls a gray notebook from a shelf and opens it. Pictures of a 3,000-foot wall are marked with lines and numbers—the record of a first ascent in Tajikistan. Such detailed itineraries, he explains, were required of all first ascents in the former Soviet Union.

Two initial photos of the peak are followed by three pages of Cyrillic text followed by black-and-white photos of the climbers themselves. He points to a dot high above the belay: a climber nailing an incipient crack on a 20-foot roof in a blizzard.

“Me,” he says.

Before perestroika, Alexander traveled every two weeks with his team around the numerous mountain ranges of the USSR. After perestroika, the professional teams collapsed. He moved to Bishkek to be close to the mountains, but he struggles to make ends meet. He is most qualified to teach climbing, but now, of course, the trade unions are gone and without them people lack the money to pay for trainers.

“Sometimes, I train young people for no money,” he says, “but it is very hard. No one helps us to go climbing, and we don’t have money to go on our own.”

His words echo everywhere. There is no money. There is no work. There is no climbing. The reality of post-perestroika alpinism is the same as life everywhere in the former Soviet Union: a stripped-down version where children in their mid-20s support their parents on salaries that wouldn’t afford a pair of jeans in the States, where the only common thing left from communism is poverty, an asphyxiating blanket that affects everyone, young and old, smart and simple, bus driver, doctor, factory worker, climber.

l remember what Vladimir told me one night over too many shots of vodka, in the basecamp tent of the British, beneath the brilliant Central Asian stars. He said that the former Soviet mountaineers, in their prime, were perhaps the best in the world, because once they had overcome the bureaucratic hurdles necessary to attempt a route, nothing could dissuade them—not winter, not weather, not lousy gear nor jumping nerves nor any of the excuses that crop up in the West.

Within the walls of communism, Soviet mountaineers ascended stunning routes on tremendous peaks in total isolation from the rest of the world. They were arguably the best-trained mountaineers on the planet, and, in 1982, when the first Soviet expedition visited the Himalaya, it successfully climbed a new route on the Southwest Face of Mount Everest that has yet to be repeated. Due to political obstruction, the next Himalayan expedition didn’t follow for seven years. When it did, the first complete traverse of the four 8000-meter summits of Kanchenjunga—one of the great feats in Himalayan history—fell to the Soviets. Later, more Soviet climbers began to climb beyond their borders, racking up Himalayan successes that continue today. But the number of climbers who made it abroad was nothing compared to those who climbed only at home.

In 1991, when the Soviet Union fell apart, Soviet climbers gained complete freedom to travel. But they lost much more. The alpine centers, the training camps and the professional teams disappeared. Today, a few commercial firms have stepped into the void, funding expeditions to the Himalayan peaks, and some climbers have organized themselves into private trade unions, paying money from their salaries into a common fund so they can keep climbing. But training for large numbers of new climbers is finished, and only the most ardent of the old school survive.

And yet the proving ground of the Soviet climbers remains, and is now open for the West—and its wallets—to explore. Soon, the soaring granite walls of the Pamir Alai will be famous, and the hospitality of its nomadic people will be widely known. Climbers from around the world will explore the high-altitude climbing of the Pamir and Tien Shan and the alpine majesty of the Ala-Archa, the Kokshaal-Tau, Ak-Tau and Karakol ranges. With them will come some money. Other funding, one hopes for the sake of the people, will come from other sources, and the Commonwealth of Independent States may find its economic heartbeat, struggle back to its feet, and begin to function once more. Then, maybe, its climbers will enjoy a renaissance—but until then, there isn’t enough money for the people to go climbing, and the system that raised generations of the world’s best mountaineers is forever gone.