Available only to you, our Patrons, this Unabridged version of Episode 6 follows the mountain troops to Mount Rainier National Park where, in the middle of February 1942, they began their ski training at one of the best places a soldier could ever learn to ski—a place called, appropriately enough, Paradise.

The episode includes interviews with Ninety-Pound Rucksack board members:

- Lance Blyth, the Command Historian of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) and an Adjunct Professor of History at the United States Air Force Academy.

- David Little, the historian for the Tenth Mountain Division Foundation

- Military historian and museum professional Sepp Scanlin

See here for biographies of characters introduced in this episode.

This Unabridged version of Episode 6 features the following exclusive content:

- Complete transcript of the episode

- Historical imagery illustrating the events covered in the episode

- A chronology of events related to the episode

Tier 2 ($10/month) and Tier 3 ($15/month) Patrons also receive:

- Bonus Episode 1: an interview with professional trainer and world-renowned alpinist Steve House on the training protocol put together for the mountain troops by The American Alpine Club

- Bonus Episode 2: an interview with Kit DesLauriers, the first woman to ski the seven summits, on the regiment’s ski mountaineering training from the perspective of the modern ski mountaineer

- Bonus Episode 3: The original recordings of the songs the mountain troops used to sing at Paradise Lodge on Mount Rainier, including the one that gave Ninety-Pound Rucksack our title

Tier 3 Patrons also receive a live monthly Q&A with Ninety-Pound Rucksack host Christian Beckwith with a special 10th Mountain Division guest. Stay tuned for details!

To upgrade your Patron level and receive these additional patron perks, click here.

Patrons are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Your support allows us to pursue the show’s journalistic and educational objectives as we detail the Division’s living legacy. In return, we’re excited to provide you with access to all Unabridged content and exclusive interviews.

Thanks for listening, and enjoy the show!

Episode 6: Ninety Pounds of Rucksack

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and I’m so happy you’re joining us today, because we’re jumping right back into our story of the 10th Mountain Division with one of its most significant chapters: the ski training that began in the middle of February, 1942, in Mount Rainier National Park at one of the best places a soldier could ever learn to ski—a place called, appropriately enough, Paradise.

Thanks to the ingenuity of Colonel Onslow Rolfe, the red-headed World War 1 veteran who’d been charged with developing America’s very first mountain unit from scratch, the 700 soldiers of the 1st Battalion (Reinforced), 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment were settling into their snow-covered barracks on the southern flanks of Mt. Rainier. At the same time, our hero, John McCown, was at California’s Camp Roberts, where he was undergoing basic training in advance of joining the 87th later that spring. We’ll start today’s episode by catching up with John before going north to Mount Rainier, where some of the country’s best climbers and skiers were about to begin their training.

On June 21, 2023, thanks to this podcast, the 10th Mountain Division renamed its Light Fighter School in John’s honor, a testament to his service to both division and country.

Before we begin, I’d like to make a note about the recreation of events related to John in this and other episodes.

Ninety-Pound Rucksack’s factual background relies upon detailed accounts from military and civilian histories and personal records from the Denver Public Library. I’m also fortunate to have the invaluable guidance of an advisory board that is deeply immersed in the division’s story.

The information related to John McCown is more finite. His niece, Susan McCown, has compiled a collection of letters, expedition logs, photos, and family history that helps us to tell his tale. Will Holland, a writer who has been working on a screenplay about John for more than two decades, has generously shared his extensive research on him as well, aiding in the development of our narrative.

However, it is important to acknowledge that the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri, destroyed millions of World War II personnel files, including John’s. To address the gaps in his service, I triangulate from what we know about him and what we know about the division. First-hand sources, when available, inform the recreation of events related to John, while in the absence of such sources, I develop scenes with the help of our advisory board to ensure their accuracy. This approach aims to provide you, dear listener, with a deeper understanding of one man’s experience in the war, and shed light at the same time on the human dimension of the Division and its impact on American society.

Today’s episode is brought to you by CiloGear, the Portland, Oregon-based company that makes the lightest, most durable, best-fitting alpine backpacks that money can buy. I’ve been using my CiloGear 3030 Worksack on climbs here in the Tetons, and I gotta say, I’m a backpack freak and it’s the best alpine pack I’ve ever owned. The litmus test for a high quality piece of equipment for me is that it has everything I need and nothing I don’t. My Worksack passes that test with flying colors: it’s comforable, the materials are bombproof, it never gets in the way of my climbing and it does everything I need it to do when I need it—and the rest of the time, I never notice it’s there.

A number of years ago, when I was running Alpinist Magazine, we gave the CiloGear Worksack our Mountain Standards Award. I’m happy to report their rabid attention to detail and focus on function are still very much alive. If you’re in the market for a killer alpine pack that will last the rest of your life, check out Cilogear at cilogear.com. Or check out their military pack systems at CGStrategic.com and enter the code “Ninety-Pound Rucksack” to get 10% off your next order.

Ninety-Pound Rucksack is made possible by our community of patrons. If you’d like to hear exclusive interviews with some of America’s top alpinists, please go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. For $5 a month you’ll not only help to support the show; you’ll get exclusive, behind-the-scenes content available only to patrons.

Patrons will receive two special interviews related to this episode. Professional trainer and world-renowned alpinist Steve House examines the training protocol put together for the 87th by The American Alpine Club, while Kit DesLauriers, the first woman to ski the seven summits, explores the regiment’s ski mountaineering training from the perspective of the modern ski mountaineer.

But wait—there’s more! Patrons will also receive the original recordings of the songs the 87th used to sing at Paradise Lodge on Mount Rainier, including the one that gave us our title.

So go to christianbeckwith.com and become a patron—and while you’re there, sign up for the newsletter so you never miss an update, give the show five stars on your podcast app, leave a review and tell your friends about it and help us to keep it all going.

And now, let’s catch up with John McCown as he begins his transformation from mountain-climbing law student to a soldier in the United States Army.

[line break]

The crisp morning breeze at Camp Roberts cooled the sweat on John’s forehead. He and the other recruits had gathered on the parade ground before dawn for calisthenics, and the air echoed with the sound of barked commands and marching platoons.

The attack on Pearl Harbor and America’s entry into the war had prompted a surge in enlistments, flooding the camp with fresh-faced soldiers. Many recruits, like John, had signed up for the mountain unit expecting to be sent to Fort Lewis in Washington. Instead, they were informed that the 1st Battalion of the 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment had already reached capacity. They would complete their basic training at Camp Roberts instead and transfer to Ft. Lewis later with the next group of mountain troops.

John surveyed the rolling golden hills, scattered scrub oak, and winding arroyos surrounding camp. Aside from the arid beauty of the landscape and the majestic golden and bald eagles soaring high overhead in the distance, there was little about the base that appealed to him.

It had been a grueling few weeks. The mental challenges of John’s studies at the University of Virginia had been replaced by the physical demands of boot camp. The daily routine was relentless: waking up at 0430, calisthenics at 0500, breakfast at 0600, followed by training exercises until noon. Recruits had a rushed half-hour to wolf down food that ranged from bland to unpalatable before continuing their training in the afternoon. At 1700, they had another meager half-hour to eat an equally unsavory meal. After dinner, a drill sergeant would lecture them on all the things they’d done wrong throughout the day. Their supposed one hour of personal time at the end of the day was often filled with whatever the drill sergeant thought would help improve their training or their attitudes. They barely had time to check their mail before lights out at 2100. John was hardly the only new soldier to come to the conclusion that basic training was for the birds.

John’s twenty-man platoon was now on the ground, completing their latest set of pushups. All, that is, except John, who was upright, perspiration beading his forehead as he waited for the others to finish. This was their fourth set of twenty, and the sun had yet to break free of the horizon.

Drill Sergeant Johnson, a compact man with a barrel chest and weathered features, paced back and forth before them, his voice booming as he marched. He was in his mid-thirties, but he looked like he’d been rode hard and put away wet, as the cowboys liked to say in Jackson’s Hole, and his spiteful demeanor made him seem even older.

According to other recruits’ tales during mealtime at the mess hall, all the drill sergeants were tough, but Sergeant Johnson had an extra dose of spite. Anger seemed to radiate from within him, and a Southern twang distorted his speech even more —particularly when he was swearing. John wondered if he could complete a sentence without the aid of profanity.

“Come on, maggots!” Sergeant Johnson bellowed at the recruits as they struggled to finish their pushups. “You are personally holding up the goddamned war effort! You think the Krauts will wait for you to complete your warmups? Hell no they won’t: they’ll shoot you like the pathetic dogs you are! Now stop embarrassing me and finish the fuck up!”

A fair-skinned man of medium build lay on the ground next John, struggling to catch his breath. John reached out a helping hand: to hell with the sergeant’s belittlement. “Don’t let him get to you,” John said. “He may be mean, but at least he’s stupid.”

The young man looked up, his blue eyes reflecting both exhaustion and gratitude. “John McCown,” John introduced himself, gripping the man’s hand firmly. “From Philadelphia.”

The man nodded. “Worth McClure,” he gasped. “Junior. Los Angeles.” Sweat streamed out of his red hair and into his freckled face. He was older than John, and he wiped the moisture from his eyes with the back of his hand as John pulled him up.

Drill Sergeant Johnson turned abruptly, catching sight of John assisting McClure. He seemed to balloon with anger as he marched toward them, his chest puffed out like a rooster’s.

“What’s your name, boy?” Drill Sergeant Johnson spat at John, his eyes narrowing as he pointed his square chin up at John’s jaw. John towered over him, but he stiffened as the sergeant leaned in.

“John McCown, sir!” he shouted.

The sergeant’s nostrils flared. “You think you’re better than this here maggot?” he snarled, jabbing a finger into John’s chest as his face flushed crimson. “You think he needs your help, you shit stain?”

“No, sir!” John responded, his brown eyes fixed straight ahead. He was so much taller than the drill sergeant that he could see the first few silver hairs on the top of his balding head.

“Maybe what this maggot needs is more pushups so he can be as big and strong as you. Is that what you think he needs?”

The drill sergeant’s face contorted with rage as he roared, “Alright, maggots! Thanks to Private McCown here, you’re going to do 500 pushups by the end of the morning!”

A collective groan swept through the platoon.

“You will run one mile. You will drop and do 100 pushups at the end of that mile. You will repeat until you’ve completed five miles and 500 pushups. And you will remember who made this extra R&R possible for you here today!”

McCown’s eyes clouded over. He had no qualms about angering the sergeant, but he hadn’t intended for his fellow recruits to suffer the consequences.

“And furthermore, I’m going to introduce you to your new platoon commander. His name is Private McCown, and he’s going to make sure you do every one of your goddamned pushups before chow.”

“Sir!” McCown said, his round ears marooned on the sides of his head by his military haircut. Dismay filled his expressive face. “My mistake, sir! I’ll do the pushups!”

“Hell yes, you will, private! While they do their 500, you’ll do 1,000, and you’ll finish them all by chow. And if you don’t finish by chow,” he gestured to the rest of the recruits, “you’ll all be doing 1,000 by the end of the day!”

Drill Sergeant Johnson’s fury lingered in the air as the recruits muttered their resentments. McClure shared their dismay. At the same time, he couldn’t help but admire John’s audacity. He sensed that John’s resistance had earned him a certain level of respect, not just from him but from the rest of the recruits as well.

As John turned to lead the run, his face reflected a mix of determination and remorse. He wasn’t going to let bastards like the drill sergeant break him, but he also didn’t want to become an outcast on the base. He was going to have to be smart if he wanted to figure this Army thing out.

John’s parents had raised him not to swear, and he’d never been much of a drinker. But goddamned if the Drill Sergeant’s bullshit didn’t make him want to do both.

This was shaping up to be a hell of a 12 weeks.

[line break]

On February 15, 1942, while John was acquainting himself with the pleasantries of Sergeant Johnson’s demeanor, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was updating the Allies on the state of the war. Hitler, you’ll remember, had betrayed his former ally Josef Stalin the preceding summer and invaded Russia with the intention of destroying what he considered to be the racially “inferior” Slavic populations and gain Lebensraum or “living space” for the German people. Not unlike Russia’s more recent invasion of Ukraine, Hitler’s forecast of a quick victory had been flawed. Though the Nazi army had expected to take Moscow within months, their offensive had stalled amidst the plunging temperatures and blizzards of winter, and in early December Russian forces had turned the tables by launching a counter offensive of their own.

Mr. Winston Churchill:

How do matters stand now? Taking it all in all, are our chances of survival better or worse than in August, 1941? Let us take the rough with the smooth…. The first and greatest of events is that the United States is now unitedly and wholeheartedly in the war with us. …

When I survey and compute the power of the United States, and its vast resources, and feel that they are now in it with us… all together, however long it lasts, till death or victory, I cannot believe there is any other fact in the whole world which can compare with that….

But there is another fact, in some ways more immediately effective. The Russian armies have not been defeated. They have not been torn to pieces. The Russian peoples have not been conquered or destroyed. Leningrad and Moscow have not been taken. The Russian armies are in the field…; they are advancing victoriously, driving the foul invader from the native soil they have guarded so bravely and loved so well.

More than that, for the first time they have broken the Hitler legend. Instead of the easy victories and abundant booty which he and his hordes had gathered in the west, he has found in Russia, so far, only disaster, failure, the shame of unspeakable crimes, the slaughter or loss of vast numbers of German soldiers and the icy wind that blows across the Russian snow.

——

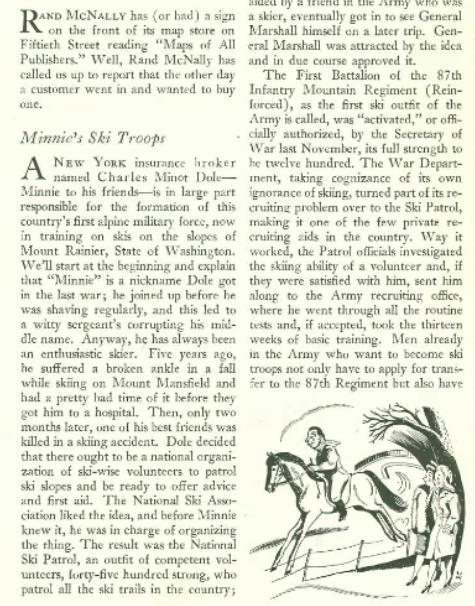

Germany’s unfolding disaster in Russia had confirmed to the War Department the importance of cold-weather training. Recognizing the limits of its expertise in the matter, the Army had retained the assistance of civilian organizations to help develop its new test force. In the fall of 1941 it had signed a contract with the National Ski Association that designated its National Ski Patrol System as the official recruitment agency for the 87th; it had furthermore requested that the NSPS find some 2,500 soldiers for the unit in sixty days.

Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board member Lance Blyth is the Command Historian of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) and an Adjunct Professor of History at the United States Air Force Academy. Here’s how he describes the Army’s contract with the National Ski Assocition.

[Lance Blyth]

“This has never been done before; it has never been done since—for a civilian agency to recruit personnel for the US military. And this is the classic “three lettermen.” They put advertisements out there in a variety of places and they said, ‘Hey, if you have experience in the outdoors skiing or camping or any of that sort of thing and want to join’—they often said, ‘ski troops’—’send us your resume with three letters of recommendation attached to our address here in New York and we will then, if you meet the standards, we will pass you onto the army.’ And the Army had it set up that if an individual was vetted by the National Ski Patrol system, they would be sent to the mountain troops—in this case, to Ft. Lewis.“

The Army had turned to The American Alpine Club for help with specialized gear, clothing and techniques, and it had asked the AAC to look for potential mountaineering instructors like John among its membership as well. And while the Army had not formally engaged with the Sierra Club, the Californian organization had nonetheless sent out information about the mountain troops to its nearly 4,000 members in the late fall of 1941. At the same time, a coalition of board members from the Club’s Rock Climbing and Mountaineering sections had begun working with the NSPS and AAC to aid the war effort in any manner possible.

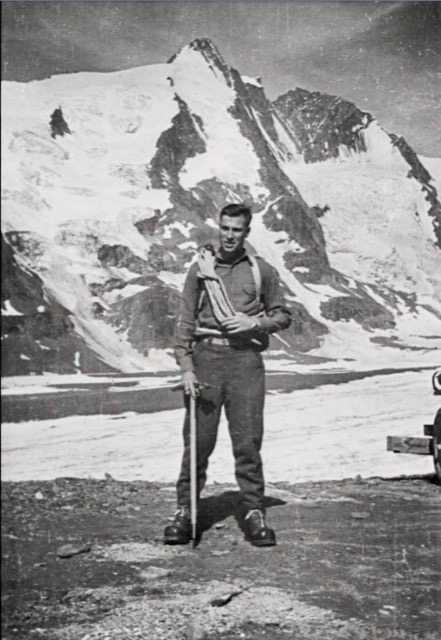

Two days prior to Churchill’s speech, the 87th’s cold weather training had begun in earnest. The 700 men of A, B and C Companies had boarded buses in Ft. Lewis and begun the sixty-mile journey to their new barracks in Paradise. Among them were a number of skiing and mountaineering experts we’ve met in previous episodes, as well as new recruits such as Private Charles Bradley.

Bradley was a thirty-year old ski jumper and cross-country skier from Wisconsin who’d closed down his photography business half a year earlier to join the Army once war appeared inevitable. Like many of the men on the buses, Bradley had both skiing experience (albeit of the Nordic, rather than the downhill, persuasion) and a college education. His original assignment in the Army had been to the Medical Service, which would have made more sense had he possessed a medical background, and he’d quickly engineered his transfer to the 87th instead.

Bradley had fallen in love with the Sierra Nevada mountains as a youth, and he’d been among the first dozen men to join the 87th at Ft. Lewis, arriving hot on the heels of Charles McLane, captain of the 1941 Dartmouth Ski Team and the first enlisted man to join the unit. Bradley had been assigned to A Company, where he was under the command of northwestern ski mountaineering pioneer Captain Paul Lafferty, who had led some of the Army’s exploratory ski patrols on Mt. Rainier the winter before.

Private Bradley would go on to write a book about his experiences entitled Aleutian Echoes. In it, he recalled the bus trip to Paradise, “where the well-plowed roads lay in snow canyons deeper than the buses,” he wrote, “and where my quarters on the first floor of the lodge required me to climb to the third floor to step out of doors. Paradise? Right on! A place to study war? Too weird to think about.”

McLane lent additional detail in an article in the 1943 American Ski Annual. “At 5,500 feet we were at the edge of the timberline,” he wrote. “Below us were thick forests of spruce and pine, excellent terrain for the maneuvering we would do after we learned to ski. Above were snowfields stretching up to 10,000 feet where a fringe of ice falls and cliffs kept the upper cone of the extinct volcano reserved for only the best mountaineers.”

Colonel Rolfe had negotiated the lease of Mount Rainier’s Paradise and Tatoosh lodges from the National Park Service, and an instructor core of skiing superstars had assembled to teach the soldiers of the 87th to ski.

[Lance Blyth]

“I mean Paradise Lodge, they must have thought was so aptly named.

“They were learning to ski; if they knew how to ski, they were testing equipment. It must have been a blast—and you had all the best skiers in the country. You had one of the best ski coaches in the country there.”

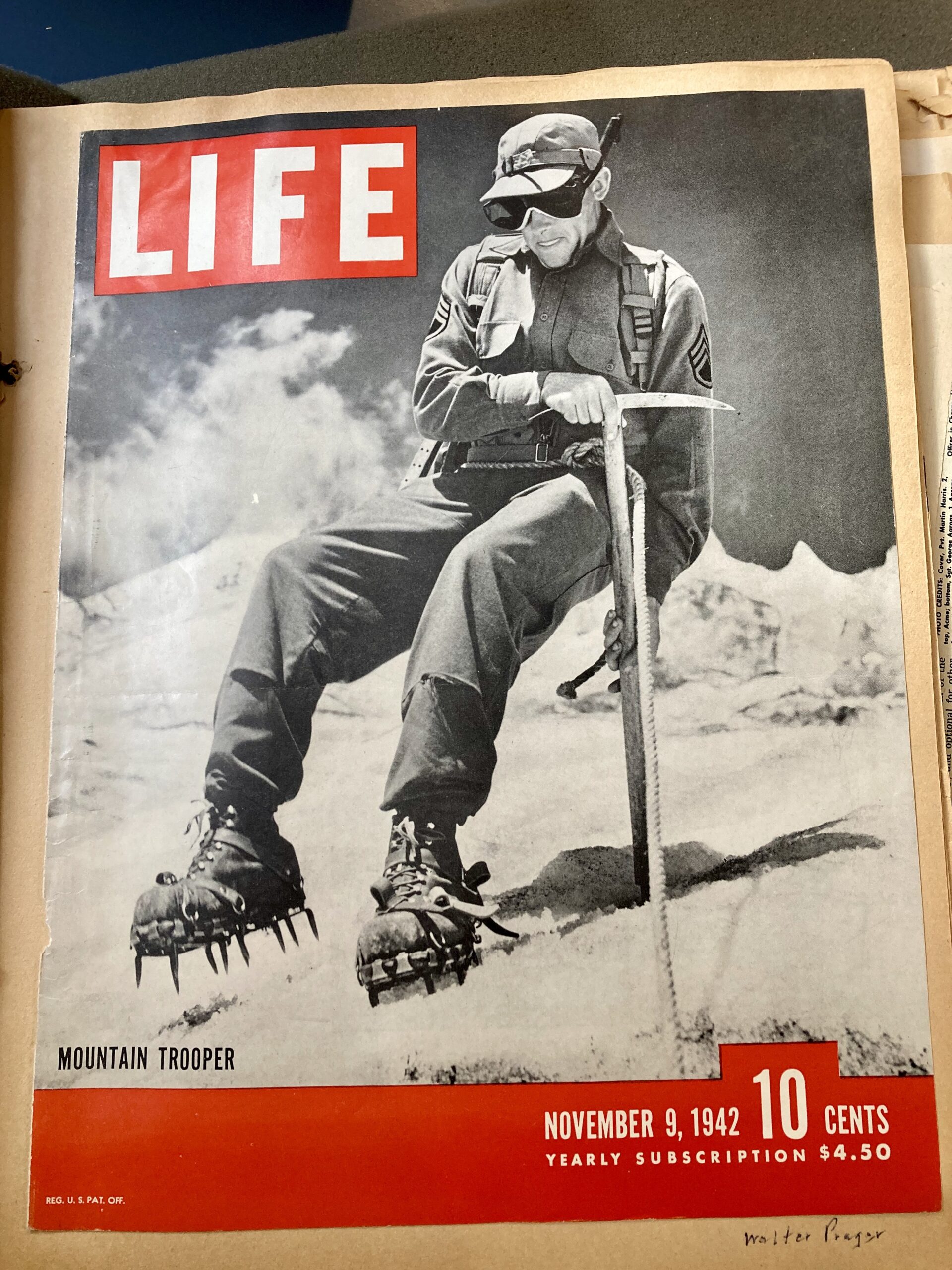

[Christian Beckwith] He’s referring to Walter Prager, the world’s first downhill ski champion and coach of the Dartmouth ski teams.

[Lance Blyth] “I mean, imagine going out and you discover your ski coach, your ski instructor is Lindsey Vaughn or Michaela Schiffrin. I mean they were like, ‘holy cow. Okay, hang on, we’re gonna go.'”

The instruction began the day after they arrived in Paradise. For six hours a day, six days a week, they began to learn everything there was to know about skiing—or, to be more precise, about the form of skiing that had been ubiquitous half a dozen years earlier.

As we’ve detailed elsewhere in this series, skiing in America had taken off with the advent of rope tows and chair lifts in the mid-1930s. There would be no chairlifts to the tops of Nazi-held summits in the Alps, and the kind of skiing in vogue on America’s ski slopes wasn’t the kind the Army needed. “Civilian skiing is nearly all downhill skiing, with no excess weight being carried,” Colonel Rolfe explained. “Military skiing teaches the individual to operate not only downhill but across country with a heavy pack and accessories, and to develop proper stamina and form.”

Lieutenant John Jay, who’d helped make one of the Army’s only training tools on the subject, a Hollywood-quality film entitled The Basic Principles of Skiing, concurred. “[T]he graceful sweeping turns of civilian skiing were out,” he wrote in his history of the unit. In its place was a kind of skiing that, sixty years later, would start to become popular once more as backcountry skiing.

To Lafferty and his fellow instructors fell the job of teaching large numbers of men to move efficiently up, down and over snow-covered terrain. Some of these men, like Bradley, had cross-country experience that made them quick studies. Others had never seen a rope tow or, for that matter, snow. The instructors, out of necessity, started with the basics: how to choose the right length of ski (it should brush the top of your outstretched hand), how to adjust cable bindings to fit the blunt, square toe of the single-leather ski boots, how to file metal ski edges, and how to give skis a proper wax.

Once they’d gotten the troops into their skis, the instructors taught them how to glide, herringbone, kick, and switchback. Young men who had never seen snow before learned to snowplow. They learned to perform right and left stem christiania turns. They sidestepped. They kick stepped. They step turned. They linked stem turns on slopes of 15 to 20 degrees until they could demonstrate complete control. And they learned how to get to the top of mountains the old-fashioned way: by hiking or with the use of climbing skins.

But it wasn’t enough to show them how to ski: the instructors also had to teach the men how to move safely and efficiently in all mountain terrain and all conditions.

To expert skiers such as McLane, the remedial components of the training entailed “…eight weeks of painless monotony, and a dozen or two broken legs, which would heal long before next winter.” To others, he wrote, “[t]he winter at Paradise would be remembered as the finest season of them all. Soldiers from Texas and Nebraska and North Dakota, whose interest had been in the flatland and city streets, made a discovery that would change their attitude. On Mount Rainier they caught hold of something they couldn’t shake off….” For these soldiers, their volcanic baptism would stand out, McLane wrote, as “the highlights in their Army careers.”

And all the learning and training took place in Rainier’s shadow. “We never got over the hugeness,” McLane remembered. “On days when there was a low ceiling we were always surprised to see the cone framed in a cloud-break thousands of feet higher than we expected.”

Once they’d learned to ski, the troops enhanced their mountaineering capabilities with additional manuevers. Over in A Company, Captain Lafferty took his soldiers on long tours up, down, in and around Paradise.

“[W]e carried packs,” Private Bradley recalled, “lightly loaded with extra clothing, matches, food, light sleeping bags, and other necessities. As time went on the loads in our packs increased to include overnight and cooking equipment. Our backs and shoulders were toughening up and we were learning some of the difficulties arising from barreling down hill with a heavy load riding high on our backs that has its own inertia, power and direction. When we were finally carrying rifles, a common misjudgment of speed and control could end in the load lifting the skier off the snow, rolling him forward in the air, and driving him head first back into the snow. The rifle, lagging slightly, would now catch up and deliver the coup de grace by whacking the skier on the head and driving him still deeper into the snow.”

The weight of the soldiers’ packs grew in tandem with their skill sets and their stamina. A one-day patrol might entail a forty-pound pack, and the weight went up from there in proportion to the length of the mission. A table in Lieutenant Jay’s history meticulously details the “typical load” in multi-day packs, which included, among other things: 1 bag, Sleeping, 12 pounds, 11 ounces; 1 bayonet, 1 pound, 8 ounces; 1 rifle, M1, 9 pounds; ½ Tent, Mountain, 6 pounds 3 ounces; 4 Rations, 12 pounds. Total: 84 pounds 4 oz.

As any backcountry skier today will tell you, the lighter the load, the happier the skier. Ascending thousands of feet on skis with a forty-pound pack can be soul-crushing. Adding 10-pound M1 rifles and 20-pound Browning Automatic Rifles, and doing it in wobbly leather boots on narrow wooden skis, is nearly incomprehensible to the modern skier.

It didn’t always go over well. After one particularly long tour, the mood in A Company was foul. “[A]ching backs, chafed shoulders, bumps on the head, exhaustion [and] frosted fingers” had inspired, according to Private Bradley, grumblings of a mutiny.

When Captain Lafferty strolled by the company’s quarters, he caught wind of the complaints. Looking as fresh as he had in the morning, he approached Bradley and asked him, with his usual smile, how things were going with his squad. Bradley confessed that the day had been a bit of a workout. They chatted some more. Lafferty mentioned he’d been testing a new rucksack, and he invited the private to try it on to see how it felt. When Bradley went to put it on, he could barely lift it off the floor. What in the world was in it, he asked? The captain’s eyebrows went up a notch, and he smiled ever-so-slightly as he replied, “Oh, that. I always add a few rocks so as to keep fit for combat loads.” When news of Lafferty’s additional training spread through the company, Bradley recalled, the “bitching faded away on the night wind.”

And as they trained through fair and foul weather, they developed the sort of fitness necessary for longer and longer missions. “Our faces grew dark and tough as leather, our muscles grew hard, our reactions quickened,” McLane wrote. “There were probably few troops in training anywhere who were healthier than we at the height of our training. But that was not the important point; what mattered was that we had learned to move around on skis and were able to handle ourselves as a group in varying kinds of snow and rain.” They were becoming mountain athletes.

[line break]

In early 1942, Minnie Dole, the Director of the National Ski Patrol System, together with the National Ski Association’s Director, Roger Langley, embarked on a countrywide tour of the National Ski Patrol System’s divisions to promote the War Department’s plans for a mountain unit. The tour took them from Chicago to Denver to the mining town of Butte, Montana, and on to Salt Lake City. From there, they continued to Seattle, then drove to Mt. Rainier, entering Paradise Lodge through a tunnel.

The New Yorker, a gossipy, high-falutin’ weekly for supercilious Manhattanites that features as its mascot a gentleman dandy in a high top hat perusing the behavior of a butterfly through a monocle, had just published a three-column essay in the front of the magazine entitled “Minnie’s Ski Troops.” The essay celebrated Dole’s role in the formation of the 87th. Dole and Langley arrived in Paradise just in time for lunch, and were quickly surrounded by friends from eastern ski slopes.

Colonel Rolfe was on hand to greet them as well.

“Pinkie led me by the arm to a large bulletin board,” Dole recounted in his biography, referring to Rolfe by the nickname he’d earned at West Point for his red hair. “Plastered in the middle of it was my bête noire–the New Yorker article … .I don’t think Pinkie was very impressed with it, or me, or the idea that I was inspecting for the War Department. Also, I was sending him a lot of college kids.”

In Dole’s telling of the story, the college kids–especially the ones from the east—confided to him that Colonel Rolfe’s attitude needed an adjustment. He failed to realize, Dole wrote, “the potential of soldiers on skis and the value of their mobility in mountain warfare.” Dole pointed out to the eastern skiers that, in Rolfe’s defense, their attitudes needed some adjustment as well. The 87th was, after all, a test force, without precedent in American military history, and the three-letter men “did not realize the amount of improvising that Pinkie, lacking detailed directives from Washington,” was being forced to do.

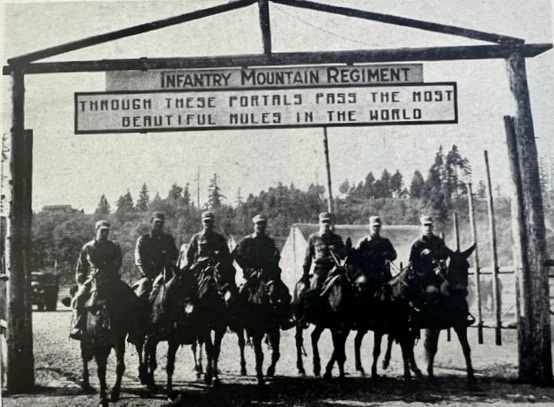

Dole and Rolfe had a sit-down to discuss the situation. “By mess time,” Dole wrote, “Pinkie’s spirits had risen considerably, while the level of my carefully hoarded bottle of Scotch had lowered.” Rolfe asked Dole to address the troops and explain to them why they had been sent to Ft. Lewis. Once he’d finished, Rolfe thanked him and took over the address. “You men seem to have the idea that you’re ski troops,” he said. “Well, you aren’t. You’re mountain troops and anyone who knows anything about the mountains knows that we have to have mules to carry equipment and mountain artillery.”

“And mules won’t go anywhere without a little bell mare to lead them. We will have a little belle mare any day now and I propose we name her ‘Minnie.’”

Dole thought that perhaps he was being compared to the working end of a mule.

Mules? What do mules have to do with our story?

Let’s pause for a moment as 10th Mountain Division Foundation historian and Ninety Pound Rucksack advisory board member David Little (with the help of his dog, Riva) illuminates a topic that will play a pivotal role in the development of America’s mountain troops.

[David Little]

“A light infantry unit—the concept of the 87th Mountain Infantry—was a rapidly deployed, self-transporting force. They didn’t need trucks or wagons to get into combat. They could march where they needed to go. And following that would be the mule train, bringing the supplies of ammunition, their artillery, their food—anything that they would need could be transported on that same gravel road or mountain path.

“In all previous mountain operations, both in the US military and the civilian world, mules were a standard form of transport. It’s slightly smaller than a horse—around an 800 pound animal—that can haul a 200 to 250 pound load on its back when the trucks got bogged down. You could transfer the load to a mule and split a truckload up among several mules and a mule will walk in basically the same path that a man will walk. The mule could go all the way up to the front lines through the mud following footpaths and can transport a goodly amount of equipment. This was the only way to get things through impassable terrain. You could hack out a path for a man and a mule would follow that path.

“The Mountain Howitzer, which was a World War I design, adopted by the army, could be broken down by six pieces. Each of those six pieces could go on a mule. And this way a1400-pound artillery piece that is about six foot wide and 12 foot long could be transported into a battlefield on top of a mountain where there is no road. And this was key to the survival of these soldiers. They had to have all of the army technology available to ’em.

“In addition, the mules could help evacuate casualties. They could be ridden at twice the speed of a man marching, which allowed you a faster resupply time. Evacuation of casualties; bringing in food and supplies: these were critical. They had to have some method of doing it. And the US Army Jeep, which was developed in 1940 and ’41, was just now coming online, but it could not walk in the path of a man.

“[The mule] was probably the only piece in the inventory that was sitting on the shelf and ready to be used. So as we developed this concept of mountain infantry, we looked to the Europeans, the Italian Alpini, the German gebirgsjager, and we looked at how they were transporting their heavy equipment and it was by mule. Well, we have those and we had packed saddles ready to go sitting on the shelf that could be adapted to most of the equipment that we would be using. So off the shelf that came and the 87th Fountain Infantry got mules.“

Colonel Rolfe might not have known anything about skiing, but he did know mules. He’d been an artillery officer in World War I, when equine strategy played a significant role in military considerations. Problematically, skiing was how the National Ski Patrol System was selling the unit. The conflict between Minnie Dole’s sales pitch and the Army’s actual needs created a tension, as military historian and Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board member Sepp Scanlin points out, that would dog the division for the next three years.

[Sepp Scanlin]

“The development of the division pursues two different goals. The skiing aspect is really born out of the Finnish winter war and the efforts of the National Ski Patrol, which is okay, but from the military officer’s perspective, they’re less interested in skiing because in their view we can march, we can put on snowshoes, we can transport, which is really how they saw the skis being used. But what we don’t have expertise on is on mountaineering. Like if you look at the Alpine Front, it was not a ski war, it was a mountaineering war. And I think this is probably best demonstrated with the early growing pains between Colonel Onslow Rolfe, who’s developing the 87th, and Minnie Dole when he visits Ft. Lewis. They don’t see eye to eye for much of the engagement. Colonel Rolfe is very much of the opinion that he’s building mountain troops, whereas Minnie is constantly talking the ski troops. And famously, and I think in in Minnie’s memoirs, he talks about how Colonel Rolfe brings him out and points to the article ‘Minnie’s Ski Troops’ and tells him that’s not what we need. We are building mountain troops because it’s broader than skiing. I need more than skiers. I need mountaineers, I need muleskinners. I need all these extra skills that aren’t brought to the table when you just call us ski troops.

“Minnie didn’t understood that, but what Minnie understood that that maybe the military people didn’t was the salesmanship piece. The number of skiers versus the number of mountaineers in the United States just gives you a bigger recruiting pool, right? It’s a numbers game. John Jay’s movie that’s used to recruit for the division, it’s a ski movie.“

(He’s referring to the War Department’s 1941 training film, The Basic Principles of Skiing, which Jay directed and produced.)

“People are inspired by the skiing aspects, right? It’s very picturesque. It’s as seen as an elite sport. The Hollywood elite are doing it places like Sun Valley where they film the film, those types of things are really a great sales pitch. Minnie sees it like, ‘Hey, this is recruiting gold, right? We’re gonna get troops like this. What you do with ’em when I get ’em to you, if you call ’em mountain troops and you teach ’em to climb ropes and walk on snowshoes, I get it.’ Nobody’s gonna join the army to do that because it’s, it’s somewhat intimidating. Where skiing seems like it has a more public appeal. You see that in some of the obstructionism, right? So the early complaints about the division and the training that’s going on at Fort Lewis is that the 87th is the army ski club. They’re just up there skiing and having a busman’s holiday. Mountain warfare is anything but a skier’s holiday. It’s going to be the toughest combat the army will see.“

Dole, with his aristocratic background, had little in common with a career Army officer like Rolfe, so it’s no wonder they didn’t always agree. But the men of the 87th saw things differently.

“Colonel Rolfe was a brilliant choice” to lead the regiment, McLane wrote in his essay. “With his wide military experience and precision, he combined an open mind and willingness to be advised. He frankly admitted he was ignorant of mountain and winter warfare, and set the precedent, unique in the army, of listening to privates and corporals who had something worthwhile to say…. There was no detail he was willing to leave unnoticed; his curiosity was penetrating. And his interest extended to everything pertaining to his regiment, both military and social. In the manner that only army men understand, Colonel Rolfe demanded our respect and devotion, and was — exactly as it should be – the most popular figure in the regiment.”

Rolfe was, first and foremost, a good leader, and good leaders never ask others to do anything they wouldn’t be willing to do themselves. He not only listened to the input and suggestions of the mountaineering experts under his command; he learned to ski right alongside all his other soldiers, enhancing his standing amongst his troops in the process.

[line break]

The instruction continued week after week. Soldiers underwent camouflage practice, learning to erase ski tracks that would otherwise reveal their locations. They honed their maneuvers in squads, and in so doing learned the importance of similar standards of proficiency lest the slowest skier impede a unit’s ability to execute. In an extraordinary moment of acquiescence, the Army permitted the suspension of all military preparation while the troops learned to ski—which was perhaps just as well, given that live fire exercises were prohibited within national park boundaries.

They learned to orient with map and compass. They developed a working knowledge of first aid and how to navigate avalanche terrain, build a two-man sled, rescue an avalanche victim and extricate him from the backcountry. At times, they served as the guinea pigs for food experiments, living on field rations of canned pork and watery soup for a week at a time as the Army tried to figure out how to fuel its mountain troops in the mountains. It all had to be figured out: the food, the gear, the clothing, the tactics and technique of skiing. The instructors argued the minutiae of form and style over dinner. While Lieutenant Jay developed meteorology reports, took photos, and shot film, Captain Albert Jackman hovered nearby as he had the previous winter at Wisconsin’s Camp McCoy, jotting notes in his small notebook that would inform future iterations of the regiment. It was all a work in progress, and everyone played their roles.

But skiing six hours a day, six days a week still leaves time for R&R, and the 87th was as serious about fun as it was about training. When the soldiers had moved into Paradise and Tatoosh lodges, they’d left the even more majestic Paradise Inn for civilian use. Come the weekend, that meant something close to a soldier’s heart: sex.

“On Saturday evenings, the Inn opened its arms to the mountain troops,” McLane wrote, “who in turn opened theirs to the scores of lonely university co-eds and Seattle woodworkers that came up to make hay while their tires lasted. Glühwein [mulled wine], yodeling, and polkas set an atmosphere that, if not unique to resort ski fans, was certainly unique to the army. The old fashioned, gangling, wooden frame building, half buried in snow, rocked and reeled one night a week until the midnight bed check retired 90% of the male attraction.”

To look back through eight decades at the unit today is to see a place and time both similar to and simultaneously worlds apart from our own. The national response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the patriotic rush to serve one’s country, the rudimentary understanding of both mountain travel and mountain warfare, the furious, concerted effort to figure out how to build the regimental airplane as it was leaving the regimental tarmac—it can all seem impossibly anachronistic. But if anything is hard to get one’s modern head around, it’s the Regimental Glee Club.

Glee clubs first appeared in London at the end of the 18th century. A century later, they began to show up in America, primarily among the well-to-do. Harvard’s formed in 1858. By 1900, they’d spread through the Ivies and public institutions alike. Given the preponderance of college-educated soldiers in the ranks of the 87th, the bonding experience of hundreds of young men learning to ski in service to their country, and the joy of doing so in one of the snowiest places on earth, it’s little wonder a regimental Glee Club quickly bubbled up in Paradise.

Organized in the dark pre-Christmas days on Ft. Lewis, the group, which was originally dubbed the Government Issue Choir, comprised twelve officers and enlisted men who sang, at the start, for themselves. A ski instructor from Sun Valley wrote most of the songs. Charles McLane was part of the Club; so was Charles Bradley. Under Lieutenant Jay’s managerial direction, the group quickly rose to fame, singing at a Parent Teachers Convention, for a commanding general of the Army, and finally, to conclude their season, before an audience of fifteen hundred in Seattle.

But the performances you and I would have wanted to witness took place on Saturday nights at Paradise Inn.

“The repertoire was small,” McLane wrote, “and before the end of the winter Paradise fans knew most of the songs by heart.”

The songs memorialized their training. One shone a light on insights that might have seemed obvious: “There are systems and theories of skiing,” the lyrics went, “But one thing I sure have found/While skiing’s confined to the winter/The drinking’s good all year round.”

Another, entitled Ninety Pounds of Rucksack, celebrated the loads the soldiers carried; it also lent this podcast its name.

[Ninety Pounds of Rucksack song]

I was a barmaid in a mountain inn;

There I learned the wages and miseries of sin;

Along came a skier fresh from off the slopes;

He’s the one that ruined me and shattered all my hopes.

Singing:

[Chorus:]

Ninety pounds of rucksack

A pound of grub or two

He’ll schuss the mountain,

Like his daddy used to do.

He asked me for a candle to light his way to bed;

He asked me for a kerchief to tie around his head;

And I a foolish maiden, thinking it no harm;

Jumped into the skier’s bed to keep the skier warm..

Singing:

[Chorus]

Early in the morning before the break of day,

He handed me a five note and these words did say,

“Take this my darling for the damage I have done.

You may have a daughter, you may have a son.

Now if you have a daughter, bounce her on your knee;

But if you have a son, send the young man out to ski.”

Singing:

[Chorus]

The moral of this story, as you can plainly see,

Is never trust a skier an inch above your knee.

For I trusted one and now look at me;

I’ve got a b*stard in the Mountain Infantry.

Singing:

[Chorus]

The Army uses basic training to build camaraderie. But basic training, as we’ve pointed out, sucks.

The training the soldiers of the 87th were undergoing that winter in Paradise was the opposite. It was fun, which is why they loved to do it. The esprit de corps that began to emerge as a result was stronger than anything basic training could build.

Three years later, in the mountains of Italy, the 10th Mountain Division would be asked to do what the US Army’s 5th Army had failed for 500 days to do before them: break Hitler’s Gothic Line, force the German surrender and end the war in Europe. The engine of their success would be their self-reliance, stamina, fitness and fellowship, and its fuel was love. There is no stronger motivation, and no more powerful bond, than that.

[line break]

In mid-April, with eight weeks of training under the soldiers’ ski suspenders, it was time for the Army to measure their proficiency. For that, it needed a test. It got two.

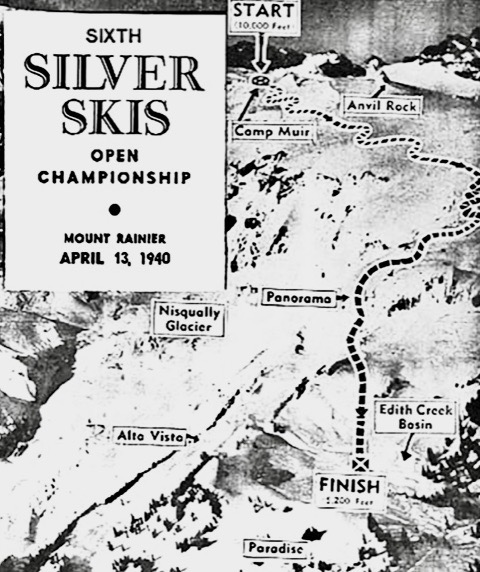

First up was the annual Silver Skis, the audacious ski race on Mount Rainier that had risen to infamy before the war. As we detailed in the last episode, the race began with a four-hour ascent from Paradise Inn up the glaciated southern face of the volcano to Camp Muir, a perch of horizontal terrain shoehorned into a ridge of volcanic rock at 10,200 feet. From there, it rolled and plunged 4,600 vertical feet over the course of four and a half miles back to the finish line in front of Paradise Inn.

On April 12, fifty-four competitors, including twenty-five soldiers from the 87th, entered the race. The presumed favorite was a corporal with the 87th who had run the course in four minutes and two seconds the day before, shaving 49 seconds off the record time in the process.

Civilian and Army competitors alike climbed to Camp Muir, rested for an hour, then began to queue up behind the starting gate. One by one they dropped, straining to control their hickory skis as they arced around rock pockets and across rutted snow. With their knees pushing their stomachs into their throats, they willed their legs to hold over steep rollovers before flying down the last half of the course at breathtaking speeds of up to 60 miles per hour.

Granted, the Army skiers had an advantage: they’d been practicing on the slopes for weeks. But when the snow settled, four out of the top six and thirteen of the top 20 finishers were mountain troops.

The results made headlines around the country, but the Army needed more than a civilian ski race to test its troops. Enter one of the country’s greatest mountain minds, and a man we’ve encountered in previous episodes: the Sierran mountaineer Bestor Robinson.

Robinson, as you’ll remember, was a climber and ski mountaineer of the first order, and part of the pioneering group of Sierra Club climbers that had created the first distinctly American school of rock climbing. In the early 1930s, he’d helped evolve both the tools and techniques of climbing, devising tests to measure the efficacy of rappels, determining how much weight a belayer could actually catch in a fall, and testing the breaking strength of pitons and carabiners. He’d then applied what he’d learned to some of the most outrageous climbs the country had ever seen.

Europe has the Alps. America has walls, and Yosemite Valley is their crucible. In 1934, Robinson and his fellow Sierra pioneers had assembled the most advanced collection of climbing gear in the country and launched America’s big-wall era with an ascent of the Valley’s Higher Cathedral Spire. Intensely curious and an inveterate tinkerer, Robinson was brilliant: he had received his law degree from Harvard in 1922 before joining his father’s law firm. He was also a badass. He’d been elected to The American Alpine Club in the late 1930s on the basis of his climbs, but he was a pioneering ski mountaineer as well: over the course of four winters, he’d put together a 300-mile ski itinerary along the crest of the Sierra Nevada, dialing food rations (which he got down to two pounds per person per day), drilling holes in his toothbrush handles to save weight and whittling away at tents, stoves, and sleeping bags until he’d reduced the weight of his multi-day pack to a remarkable fourteen pounds.

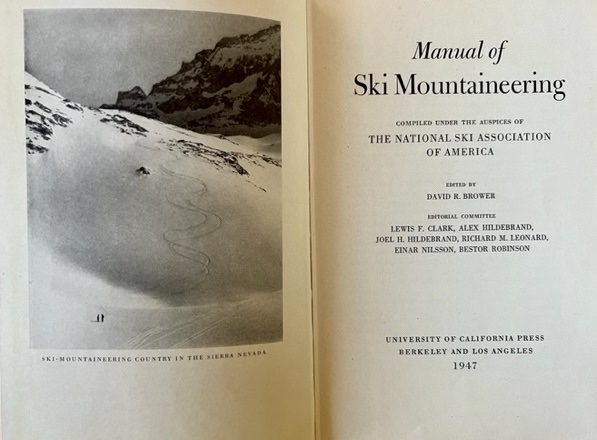

Though the National Ski Association had adopted uniform ski touring tests for civilians at its annual meeting in 1940, the Army and its military skiing required a new kind of exam. The National Ski Association appointed Robinson the chair of its Winter Equipment Committee and, the day after Pearl Harbor, directed him to develop a manual the Army could use to test its mountain troops and teach them the fundamentals of ski mountaineering at the same time.

Robinson called on his partners from the Rock Climbing and Mountaineering section of the Sierra Club to help. The resulting Manual of Ski Mountaineering, which came out as the 87th was beginning its ski training, was the country’s first compendium of ski mountaineering information. Edited by David Brower, who, like Robinson, would soon become a pivotal part of the mountain troops, the book covered virtually anything and everything a backcountry skier needed to know: how to wax skis, melt water, break trail, orient, select a campsite, bivouac, negotiate avalanche slopes, use a map and transport the injured. The keys to safe mountain travel in winter, information that had heretofore been scattered across the country’s few mountaineering publications, lay between its covers.

To be frank, the book’s overviews were cursory at best. A scattering of rudimentary drawings illustrated a single paragraph or at most a page devoted to topics that are the subject of advanced college degrees today. But in the spring of 1942, the Manual of Ski Mountaineering represented the sum total of America’s knowledge on the subject, all condensed into a single, slim, 200-page volume the Army could use to train and test its troops.

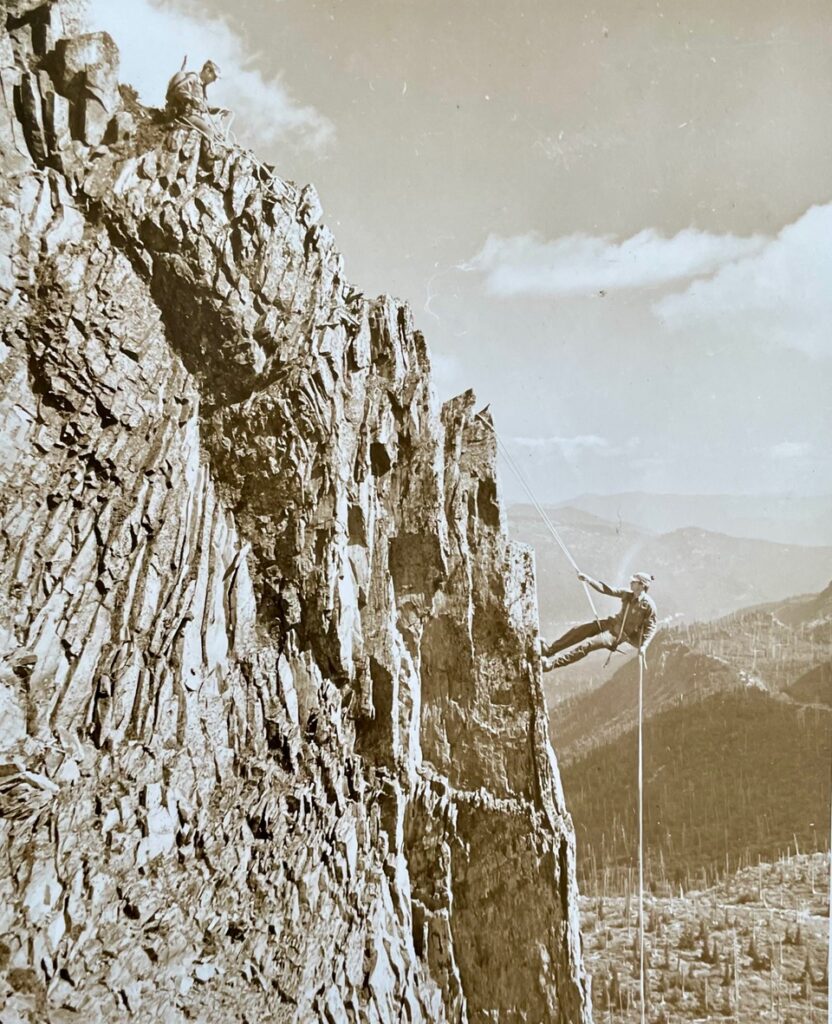

The soldiers proceeded through the test under the watchful gaze of their instructors. They skied uphill and downhill along a two-mile course while carrying forty-pound packs and rifles. They went on all-day tours, two-day tours, and multi-day tours, demonstrating their mastery of all aspects of military mountaineering. They finished with a battalion ski march, carrying packs and rifles for seven miles from the lodges, up four thousand feet on Mount Rainier, then down a glacier, over a ridge and back to their barracks in Paradise.

The results were inspired. Three-quarters of the soldiers qualified as military skiers on a course that expert civilian skiers would have had trouble handling, even without packs and rifles.

Above and beyond what the tests could tell the Army, the training had demonstrated a number of unique characteristics that would become hallmarks of the 10th Mountain Division. They’d developed initiative and self-reliance. Their esprit de corps was through the roof. Their stamina and high levels of physical fitness were extraordinary. “I do not believe I have ever seen a better group of physically trained men in my life,” Colonel Rolfe wrote to his commanding officer. The first official chapter in the history of the mountain troops was in the books.

[line break]

One of the war’s great contributions to American mountaineering was the dissemination of ideas and information amongst what had previously been insular groups. “Climbers from all over the country enlisted in the mountain troops,” wrote Chris Jones in his history, Climbing in North America, “and got their first real chance to compare notes and explore problems of technique.” They also got, for the first time in American history, not one but two compendiums of up-to-date information on how to climb and ski in the mountains.

By the early 1940s, America’s one to two million skiers gathered with regularity throughout the winter months. The skiing public went to ski areas for weekend outings. Racers convened for regional and collegiate ski meets, and events such as the Silver Skis attracted the country’s top practitioners. Publications such as Ski Magazine, The Ski Bulletin and The American Ski Annual reported the latest news and developments, while books such as Otto Lang’s Downhill Skiing provided how-tos for an increasingly curious audience. Although still in its relative infancy, downhill skiing—wherein descent was facilitated by rope tows and chairlifts—was an established sport.

Climbing wasn’t. It remained, by and large, an unorthodox, provincial pursuit, its relatively few practitioners scattered amongst a handful of locations in the Rocky Mountains and on the east and west coasts. The American Alpine Club’s American Alpine Journal was the country’s leading mountaineering publiction, but its circulation was less than 1,000. The Appalachian Mountain Club’s publication Appalachia, the Sierra Club’s Bulletin and The Colorado Mountain Club’s Trail and Timberline disseminated information as well, but, as we’ve discussed, the audience was miniscule, as the total number of mountaineering club members in the country was around 12,000.

Ever since Bob Bates and H. Adams Carter had observed the maneuvers of the Swiss mountain troops in the summer of 1939 and begun thinking about the need for American mountain troops, America’s leading climbers had been pondering precisely what those needs would entail. First, they had to deal with the fact that no training manual for cold weather and mountain warfare existed. Over the course of a year and a half, Carter, in an effort so Herculean we’ll cover it in depth in our next episode, identified, procured, and translated war manuals from the Swiss, Italian, French, Austrian and German mountain troops. When he finished, the US Army had the foundations of a mountain warfare manual of its own.

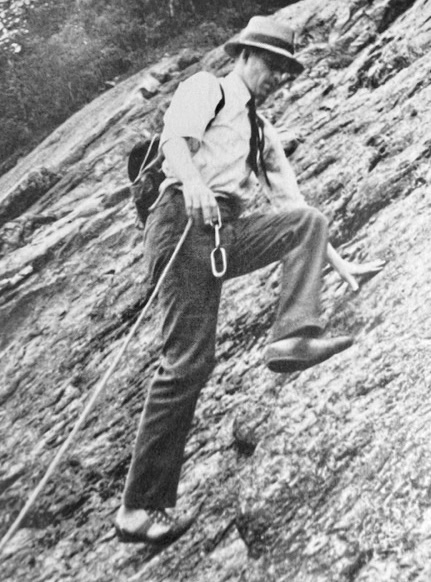

But the problem went deeper than anything such a manual could address. The Army needed a how-to book it could use to teach the soldiers to climb. As we discussed in Episode 1, the most comprehensive resource on mountaineering available to American climbers at the time was Sir Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s Mountain Craft, a 600-page, twenty-year-old British tome with a decided bias for the Alps that had enshrined the maxim, “The leader must not fall.” It was a how-to book from a bygone age and a foreign land, and it was woefully out of date.

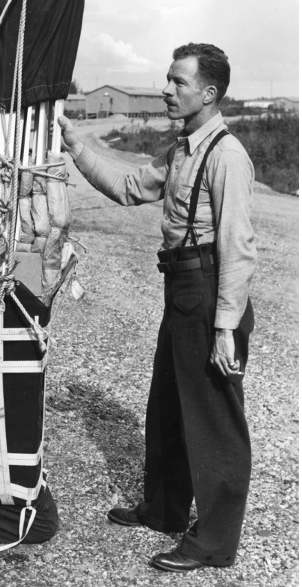

In the early 1920s, American climbing lagged far behind the standards of its European counterparts. By the end of the decade, that had begun to change, in no small part thanks to a banker from Boston named Ken Henderson.

Like other gentlemen climbers of his generation, Henderson had learned to climb in the Alps with guides, then brought his experiences, insights and European climbing equipment home and applied them to objectives on this side of the Atlantic.

In an era without specialized clothing, he climbed in a jacket and tie. He often wore a fedora. For rock climbing, he used crepe-soled golf shoes or sneakers—and in an era when every mountain outing was an adventure, he pushed the boundaries of the possible. His 1929 ascent of the Grand Teton’s East Ridge, with Robert Underhill, was longer, bolder and more technically difficult than anything previously done on American soil. Entailing old-school 5.7 rock climbing as well as snow and ice work, the route connected nearly three thousand feet of alpine terrain via two rappels. It not only stood as a test piece of American mountaineering; it also marked the first time anyone had ever rappelled in the Tetons.

In addition to his alpine talents, Henderson documented his climbs with films, edited the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Appalachia, and wrote the first guidebook to the Wind River Range. As an officer of the American Alpine Club, he developed the first guide certification process in the US as well as distress signals climbers could use to call for help.

The National Ski Association had formed its National Volunteer Winter Defense Committee in November 1940. Around the same time, the AAC had put together its National Defense Committee to assist with the gear, clothing and recruitment of mountaineering instructors from its ranks.

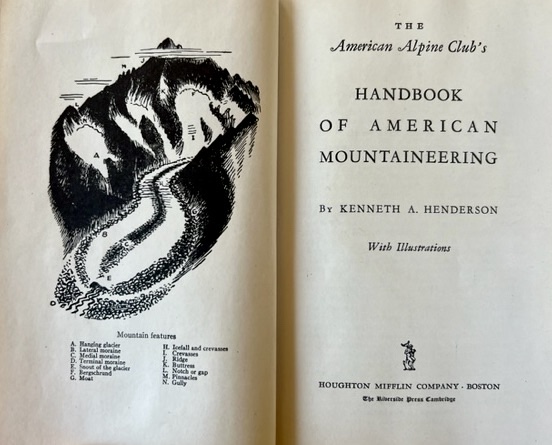

In early 1941, The AAC’s National Defense Committee, cognizant of the almost complete lack of literature on the subject, unleashed the kraken: they let Henderson loose on an effort to put together a textbook on climbing for both Army and civilian use.

For more than a year, Henderson diligently set down the fundamentals of a distinctly American school of climbing, jettisoning the European assumptions of hut systems and guides in favor of distinctly American considerations such as horsepacking, the use of airplane support for objectives in the Yukon and Alaska, and the considerations of adventures amidst Arctic conditions and extreme cold.

He modeled the book on the excellent layout of a German manual on military mountaineering and covered everything from movement over rock, snow and ice, to objective hazards and mountain rescue. He detailed how to camp in the mountains, what equipment to use for cooking, and how to manage the vagaries of mountain weather. Apart from the book’s marvelous illustrations, which depicted everything from shoulder belays to igloo building to the dangers of an ice fall, he wrote the vast majority of the book by himself, unpaid, in under a year. By December, he’d secured a publisher, Houghton, Mifflin Co. Four months later, its publication expedited by the AAC to assist with the war effort, the Handbook of American Mountaineering was released. It was available to AAC members for $1.75, and to the general public for a dollar more.

The Handbook of American Mountaineering covered some of the same ground Brower and Robinson had detailed in The Manual of Ski Mountaineering, but Henderson’s book was a more robust production, with better illustrations and far more detailed descriptions. More importantly, thanks to Robinson, Brower and Henderson, the country’s mountaineers had, for the first time in history, instructional manuals on how to climb and ski—and so did the Army.

[line break]

As the soldiers of the 1st Battalion were finishing up on Mount Rainier, John McCown was completing his basic training in Camp Roberts. If three months in the Army had convinced him of anything, it was that there was a right way to do things, and there was the Army way. The latter was beginning to earn his full contempt.

In early May, John boarded a troop train with Worth McClure and their fellow soldiers and headed north, out of the hot dry air of Central California, past the San Francisco Bay, into the state’s redwood forests and up through the mist-shrouded Douglas firs of Oregon.

Some of the infantrymen on the train were, like John and Worth, college educated. Others were fresh from high school, teenagers who had never been away from home. Sierra Club members who had responded to the questionnaire sent out by the organization in December were on the train; so were recruits channeled into the battalion by The National Ski Patrol System, which had recently been directed to broaden its pitch to include “mountaineers, loggers, timber cruisers, prospectors and rugged outdoor men.” Some of these were on the train as well, but the organization’s recruitment was soon suspended by the War Department, ostensibly because it had filled its quotas, but also, perhaps, because of the military’s latent distrust of skiers.

Suitable men from other Army units— muleskinners from the south, heavy artillery specialists, and soldiers with backgrounds, however thin, i animals or mountains or cold weathe—were on the train too as it made its way north.

John and Worth took their meals in the baggage car with the rest of the soldiers. Amidst the rhythmic clickety-clack of the train tracks, their conversations jumped from the war to their lives back home to what awaited them at Ft. Lewis.

As news coverage of the mountain troops had continued to grow, the public’s interest had surged in tandem. John’s father sent him news clippings about the unit almost daily, and now he unfolded one from the New Yorker entitled “Minnie’s Ski Troops.” He furrowed his brow as he read the article, smoothing out the creases where he had folded it to fit into his pocket.

“I don’t know why they’re calling us ski troops,” John muttered, his voice tinged with frustration, as he bowed over the article. “Henry Hall, the American Alpine Club secretary, has been writing to me, and the AAC is working just as hard as the Ski Patrol on the unit. They should call us the mountain troops.”

Worth, sitting across from John on a bench seat, listened quietly as the scenery flickered past. The intensity of John’s emotions amused him. He was like a juvenile puppy, eagerly barking at anything that caught his attention. “You needn’t get so worked up about it,” Worth said in a calm voice. “I’m not sure it matters what they call us, as long as we get to train in the mountains.”

Ignoring his friend’s response, John continued with unwavering enthusiasm. “Look,” he exclaimed, pointing his finger at a particular line in the article. ” ‘In the summer, the ski troops will practice straight mountain-climbing.’ See? We’re going to climb mountains!”

Curiosity piqued, Worth took the article from John’s hand and began reading it from the beginning. John’s right knee bounced up and down as he pressed his face against the train window. “Walter Prager will be there,” he remarked, almost to himself. “He’s the coach of the Dartmouth ski team. And Peter Gabriel, too. They’re both Swiss mountain guides. Henry Hall already wrote to both of them—I’m supposed to help them with the mountain training.”

“You’ve mentioned that,” said Worth, who’d listened to John talk about Walter Prager and Peter Gabriel and Henry Hall since the day they’d met.

John’s inability to contain his emotions was a big part of his charm; it had also been the source of more than a few of his problems in basic training. Most of the new soldiers had quickly learned to bite their ton gues when confronted with officers like the drill sergeant. Not John. His frustrations with the Army’s absurdities were exacerbated by the fact that he didn’t know when to back down. He was both whip-smart and eloquent, and, to the growing delight of their fellow recruits, hardly a mess time had passed without John cracking up the table with yet another account of an encounter with an officer gone wrong. “McCown stories,” as they’d come to be known on base, had grown to near-legendary status by the time they’d finished their training.

Worth was half a dozen years older than John, with a wife and one-year-old son waiting for him in Los Angeles. He enjoyed listening to John’s misadventures as much as anyone, but he’d also grown to feel a mix of protectiveness and responsibility toward his new friend. To him, John had become a combination of a younger brother and an older son.

When the conversations turned to the war, they both became more subdued. Neither the fight in Europe nor the one in the Pacific were going well. Germany continued to bomb the hell out of Britain. While its assault on Russia had been stymied by winter and the Soviet counter-offensive, Hitler had retaliated in the spring with massive airstrikes that were now debilitating the Red Army. In the Pacific, the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, which had begun ten hours after its attack on Pearl Harbor, had forced the American Asiatic Fleet to withdraw, stranding more than 75,000 American and Filipino defenders who would soon be put on a death march that would kill more than 10% of their numbers. Rumors circulated of German U-boats attacking American merchant ships along the Eastern Seaboard. As excited as both men were about joining the mountain troops, they couldn’t escape the reason the unit was being formed in the first place.

[line break]

“We’re here to report to the mountain troops,” John confidently announced to the guard on duty at Ft. Lewis when he and Worth arrived at the main gate.

Their expectations were hazy. They hadn’t anticipated a grand reception, but they’d secretly hoped for some form of acknowledgment that matched the mixture of anticipation and uncertainty brewing inside them.

While the guard looked over their paper, John leaned sideways to see past his shoulder. A six-wheeled transport truck thundered by, revealing soldiers in the back clinging to hooped bars beneath its canvas cover and lurching in unison when the vehicle hit a pothole. Platoons marched in formation in the distance. Rainier, the colossal volcano they had glimpsed during their train ride, was now shrouded in clouds.

“They’re with the 87th,” the soldier informed someone inside the guardhouse.

“West six blocks, cross the highway,” came the reply from within. “Camp Murray. Two miles on the right.”

“Camp Murray?” John’s voice was laced with confusion. “I thought the mountain troops were here at Ft. Lewis?”

“Son, there are 26,000 troops at Ft. Lewis,” the guard explained with a hint of exasperation. “We’ve got a national guard unit, an engineering unit, an artillery unit, and a cavalry unit. You’re in Camp Murray, across the road. It’s a sub-camp. Look for the sign.”

“What sign?” John inquired, perplexed.

“You’ll know it when you see it,” the guard replied, handing back their papers.

John and Worth proceeded across the vast base , passing a sea of marching soldiers and row upon row of identical two-story white buildings. Initially, John attempted to count them, but the sheer number overwhelmed him, and he eventually gave up.

After what seemed like hours, they crossed the road.

“Look—there it is,” Worth exclaimed.

A pine-post gate was topped by a pine-post triangle. Resting below it were two rectangular signs. “Infantry Mountain Regiment” proclaimed the one on top. Beneath it, another read, in block letters, “Through These Portals Pass the Most Beautiful Mules in the World.”

“Is this some kind of joke?” John asked incredulously.

“It’s like the sign above the Earl Carroll Theater in Hollywood,” Worth mused, a smile playing on his lips. “You know, ’Through these portals pass the most beautiful girls in the world.’”

Perplexed by the military’s sense of humor, the two men, one rugged and the other slim, entered through the gate.

[Line break]

The sign had been Colonel Rolfe’s idea, but not much else about the mountain troops was funny. Everything apart from the name had become bigger and more confusing. To the delight of military historians everywhere, the 1st Battalian (Reinforced), 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment was now, simply, the 87th Infantry Regiment, in part because a 2nd and 3rd battalion had been activated. This expansion added some 2,100 men. Now, in addition to the 1st Battalion’s A, B, and C companies, each with an authorized strength of 193 men, and the smaller heavy weapons D Company, there was the 2nd Battalion’s E, F and G companies, plus its heavy weapons company, H, and the 3rd Battalion’s I, K and L companies, plus M, its heavy weapons company. There was no J Company, because the Army didn’t trust its soldiers to be able to tell the difference between the letters J and I.

In the weeks before John and Worth reported for duty at Ft. Lewis, E Company had been deployed on a forced march to the coast to thwart a suspected Japanese attack. Lacking real weapons, soldiers held their positions on a beach for three days with simulated mortars, machine guns and aspen sticks for rifles. Other companies had been ordered from Paradise back to Ft. Lewis to take over guard duty, only to be informed they’d been relieved of said duty before they arrived.

Limited training on Rainier continued, but the end of the lease of Paradise and Tatoosh Lodges meant a two-hour bus ride just to get to the mountain. That didn’t stop the heavy weapons D Company from practicing their Rainier maneuvers, but they did so on snowshoes with eighty-pound packs. Complaints ensued.

Complaints continued when 1st Battalion instructors, expert skiers and climbers who had volunteered for the mountain troops specifically to help train its soldiers, returned to Ft. Lewis at the same low rank at which they’d begun their service. The Army recognized cooks and typists with technician’s ratings, a recognition made all the more valuable by a bump in pay. Paratroopers had patches. To their great frustration, American mountaineers who had just been teaching officers to ski were now laboring away on kitchen patrol without distinction.

John and Worth were given orders only to have them overturned by counter orders. They were assigned to one unit and then reassigned to another. John’s arrival had been accompanied by additional duties: he’d been made a squad leader. The new position of authority was perplexing—he was still only a private—but it was, as he was learning, consistent with the Army way of doing things. With three months of basic training under his belt, John’s responsibilities now included guiding others nominally less qualified then himself through basic training of their own.

One thing was certain: he’d be no Drill Sergeant Johnson. As patiently as possible, John introduced the eight men under his command to the manual of arms, the Army’s instruction book for handling and using weapons. He showed the new recruits how to march and how to fall into formation. He was supposed to make sure they had all the requisite gear, but the base was short on uniforms and rifles. For that matter, it was short on toothpaste. Hell, they’d had to set up field kitchens for the 87th because there weren’t enough mess halls. The turmoil was exhausting.

And when in the world were they going to start climbing? Henry Hall had sent John the Handbook of American Mountaineering as soon as it was published, and he’d read it cover to cover, making notes in the margins of the pages. But days turned into weeks, and weeks dragged into summer, and still the military mountaineering phase of the unit’s training failed to begin.

As with all things mountain-warfare related, the playbook for how to train a regiment to climb had to be developed from the ground up. As the Army had continued to expand at unprecedented speed through the winter, the AAC had heard from its contacts in DC that it planned to develop not one but two divisions of mountain troops by the end of summer. How did the Army expect to train 30,000 troops to climb in less than half a year’s time? It had barely figured out how to train fewer than a thousand soldiers to ski on Mount Rainier.

To address the matter, the AAC had tapped Walter Wood Jr, the esteemed geographer and explorer and the chair of its National Defense Committee whom we met in Episode 3. Conscious of the need for speed, Wood had convened some of the brightest minds in American climbing at his home in New York in late March . Hall was there, as were Henderson and Bestor Robinson. So were Bob Bates and Bill House. Over the course of a single weekend, eleven men, most of them not yet in their thirties, put their heads together to figure out not only how to train the troops, but how to train their instructors.

Within a week they’d come up with an outline. By early April they’d come up with a full-blown plan. They would prepare a six-day course of intense instruction in rock, snow and ice climbing, select a qualified body of instructors, put them through the course, then provide oversight as the instructors used the same program to train the general troops.

The course was brilliant. From climbing pace and elementary rope technique, it progressed through ice and snow travel, avalanche considerations, advanced rope work and the movement of weapons, equipment and injured personnel over vertical terrain.

To get a modern-day take on the course’s efficacy, I interviewed Steve House, one of the world’s foremost alpinists and professional trainers. The interview, which is available exclusively to patrons of the show, underscores just how groundbreaking the AAC’s training program was: it mirrored the training programs Steve has developed for his company, Uphill Athlete. The only difference is that Steve, who is in his fifties, has developed his programs over the course of three decades of cutting-edge climbing in Alaska, the Canadian Rockies and the Himalaya. The AAC climbers—who were, for the most part, in their twenties—developed the Army’s program in a weekend.

The AAC had submitted the training program to the War Department in early April. As part of their presentation, they proposed that the program be overseen entirely by the Club itself.

Perhaps the plan had landed on the desk of one of the War Department’s mountain skeptics; perhaps the proposal by yet another civilian organization to take sole ownership of a mission-critical component of the mountain troop’s training was a step too far. Whatever the reason, the proposal had gone over like a fart in church. “The mention of the possibility of the 87th Infantry Regiment becoming pupils of the proposed school appears to have been badly received by Washington,” Chairman Wood reported to his fellow AAC board members on April 11. The AAC, in its patriotic enthusiasm, had gotten out over its skis.

And now John, who had joined the 87th expecting to become one of its AAC-appointed military mountaineering instructors, was charged with ensuring new recruits could find enough toothpaste.

At the end of another long day with his squad, John made his way toward a table in the mess hall. As he did, he noticed a tall man with a deep tan bent over his meal tray. The man had racoon eyes where his glasses had shielded his skin from the sun. That could only mean one thing: mountains. And it couldn’t have been Rainier, because Paradise and its lodges were now occupied by civilians. Plus, there hadn’t been a single day of sun at Ft. Lewis since John arrived.

Eager to talk about climbing, John approached the man with a friendly smile.

“Where’d you get that tan?” he asked, sliding his meal tray onto the table and extending a hand in greeting.

The man looked up and chuckled. “Funny you should ask,” he said. “I got it from my wife.” He accepted John’s handshake. “John de la Montagne,” he said.

McCown did a double take. “Seriously? John of the Mountains?” he asked. “What, did you change your name on purpose before joining up?”

“I know,” Montagne answered. “If I had, I would have changed it to something else. I’d do anything to avoid another conversation about my name.”

“Well, that has to be the best name of any mountain trooper in history,” John mused.

Like a disproportionate number of the new recruits flooding the base, Montagne was a Dartmouth boy—the college had accelerated graduation for the class of 1942 to accommodate WWII enlistment. He’d gotten his tan courtesy of a two-week ski honeymoon with his new bride just before arriving in Ft. Lewis.

McCown’s face lit up at the mention of Dartmouth. “Do you know Walter Prager?” he asked.

“Yes, of course!” Montagne exclaimed. “He’s a legend. I trained under him for a while. He’s the reason I fell in love with skiing in the first place.”

“Would you introduce us?” John asked. “I’m supposed to work with him on the mountain training.”

“I’d be happy to,” said Montagne. “But I wouldn’t get too excited. He doesn’t think we’ll be climbing in the mountains any time soon.” John’s face fell in disappointment.

“But we’ve been talking about it, and I think there’s an alternative,” Montagne continued hopefully.

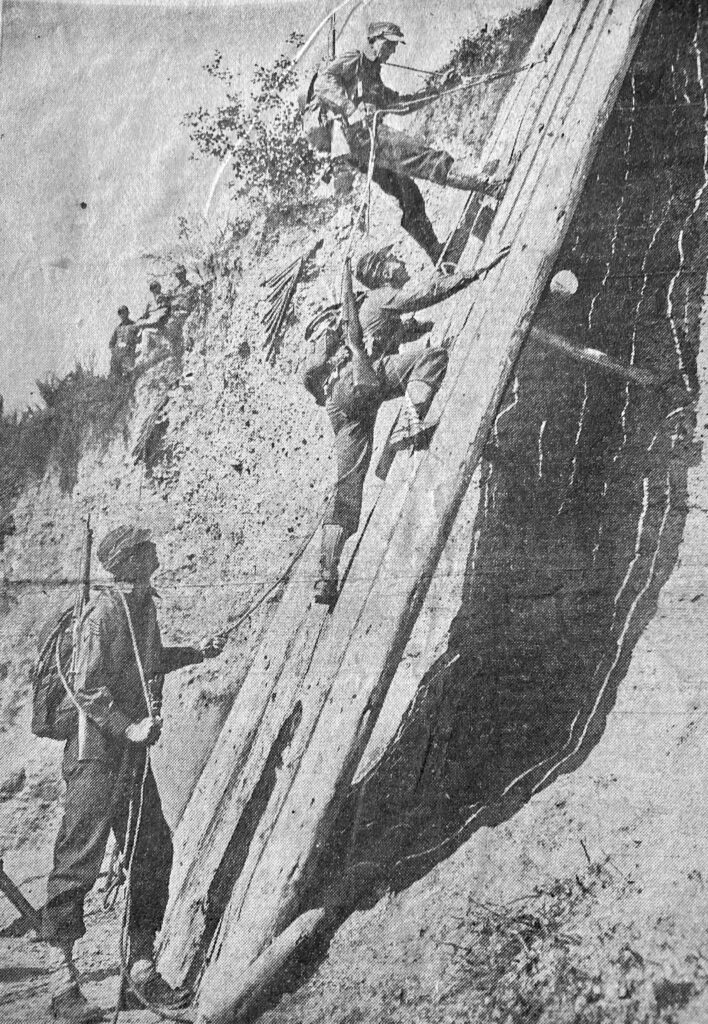

After mess, Montagne led John to a gravel pit, where they were greeted by an extraordinary sight. Sergeant Walter Prager, with the assistance of Lieutenant John Woodward, was assembling three thirty-foot panels of lashed-together logs. The logs were notched with hand- and footholds, creating the world’s first artificial climbing walls. On a base as flat as Ft. Lewis, and in the midst of the regiment’s chaotic expansion, it was an ingenious solution to the problem of teaching soldiers to climb.

John’s eyes widened with excitement. “This is incredible! Climbing—right here at Ft. Lewis!”

“Let me introduce you to Walter,” said Montagne. “You two are kindred spirits.”

As Montagne made the introductions, John sized the slender man up. Though Prager was a fraction of his size, John was more than a little awed: he was, after all, one of the best skiers in the world. And judging by the climbing walls, he was also resourceful. “Ja,” said Prager, in response to John’s questions. “It may not be vhat ve vanted, but it’s zomething. Ve can learn the fundamentals and ve can practice for the real thing.”

Over the next few weeks, soldiers and officers, including Colonel Rolfe himself, gathered around the makeshift climbing walls. Under Prager’s watchful eye, they began to learn to climb. With full military packs strapped to their backs, they scaled the logs, honing their skills and learning the intricacies of rope management, belaying and rappelling. It was a far cry from the training the soldiers needed, but under the circumstances, it was the best the regiment could do.

[line break]