Episode 2 Part 1 provides a sweeping overview of the history of skiing in America as told through the experiences of one of the 10th Mountain Division’s greatest unsung heroes, John Andrew McCown II. Episode includes interview excerpts with Paul Petzoldt, the Teton climbing legend who would join the 10th Mountain Division at Camp Hale in 1942 and be put in charge of developing its mountain rescue system.

Episode also includes an extended interview with Dr. E. John B. Allen, professor emeritus of history at New Hampshire’s Plymouth State University and the author of numerous books, including From Skisport to Skiing: One Hundred Years of an American Sport, 1840–1940, on the evolution of skiing in America before the war.

Listen to the episode here:

See here for an overview of the characters mentioned in this episode.

Available only to patrons, this Unabridged episode of Episode 2 Part 1 features an exclusive interview with Ninety-Pound Rucksack Advisory Board member Jeff Leich on the explosion of skiing’s popularity in America in the 1920s and 1930s.

This Unabridged episode also includes an excerpt from the working draft of the book, Ninety-Pound Rucksack: The True Story of John McCown, the 10th Mountain Division and the Dawn of Outdoor Recreation in America, detailing John McCown’s experience in the 1939 4th of July ski race that led to his decision to stay in the Tetons for the summer.

Thank you for being a patron of the show—you are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Your support allows us to pursue the show’s journalistic and educational objectives. In return, we are honored to provide you with exclusive access to all Unabridged content.

The State of the Art: Episode 2, Part 1

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and boy, am I excited you’re here for this episode. There is so. Much. To. Unpack.

If you’re just tuning in, here’s a quick recap to bring you up to speed. Ninety-Pound Rucksack is the story of the 10th Mountain Division, told in two ways. An Advisory Board of the 10th’s foremost experts helps ensure the podcast’s historical accuracy. We’re also weaving in the narrative nonfiction account of First Lieutenant John Andrew McCown II, a young man who learned to climb in the Tetons, joined the Division at its inception and rose through the ranks to become one of its greatest unsung heroes.

John’s story is part of a book I’ll release upon the conclusion of the podcast. Its factual foundation, including the recreation of events found in this episode, relies on first-person sources. Where such sources are unavailable, civilian and military histories of the unit and input from the 10th Mountain Division community are used to fill in the gaps.

In Episode 0 we recounted how the discovery of John’s story led to the genesis of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. In our last episode—Episode 1— we examined how the 1939 Soviet invasion of Finland, the National Ski Patrol System, the US Army, and the American Alpine Club converged in their efforts to develop America’s very first mountain unit.

If you haven’t already, make sure you subscribe to the show so you don’t miss an episode, and please consider becoming a Patron. Not only do patrons help to underwrite all our research for the show, they get access to our Unabridged content, which includes exclusive interviews, historical documents, supporting materials and photos that illustrate each episode. To become a patron, just go on over to christianbeckwith.com and click the Patreon button. It’s easy, and it makes it possible for us to continue this exciting and important work.

OK, so now buckle up, because we’re about to begin our exploration of the state of climbing and skiing in America and Europe before the war. To give each element the attention it deserves, we’re breaking this episode into two parts. Part 1 here today will drill down into the history of skiing in America. Part 2, which we’ll release next month, will provide a deeper analysis of climbing before the war, explore the history of European mountain troops, and examine how the rise of the Third Reich caused some of the best German and Austro-Hungarian mountaineers to emigrate, influencing climbing and skiing on this side of the Atlantic and contributing to 10th Mountain Division’s fighting skills.

A quick call-out to The American Alpine Club for supporting our podcast today.

The American Alpine Club has been supporting climbers and preserving climbing history for more than 120 years. AAC members receive rescue insurance and medical expense coverage, providing peace of mind on committing objectives. They also get copies of the AAC’s world-renowned publications, The American Alpine Journal and Accidents in North American Climbing, and can explore climbing history by diving into the AAC’s Mountaineering Library. Learn more about the Cub and benefits of membership at americanalpineclub.org, and get a taste of the best of AAC content by listening to the bi-monthly American Alpine Club podcast on Spotify, Apple podcasts, or Soundcloud.

The golden nubbin stood out like an inverted dimple on an otherwise smooth rock wall.

It was August 3, 1939, and twenty-one year old John McCown was perched forty feet above a bone-shattering ledge on the Grand Teton’s Exum Ridge, 12,500 feet above sea level in the pale blue Wyoming sky.

John pasted the felt sole of his right climbing shoe on a gray convexity, smeared his left on a ripple, fingered a flaring crack for purchase and scanned the stone for alternatives.

There were none. The dimpled nubbin was the sole feature in a four-foot radius—and not much of one at that.

John looked down at the ledge below; it was strewn with shards of talus and broken rock. To the east, the view dropped away thousands of feet to the plains of Jackson’s Hole. The serrated architecture of the Grand Teton’s southern walls crowded the vista to the west, with Pierre’s Hole in Idaho shimmering in the heat just beyond. He’d never been so high or exposed in his life.

He wished they’d brought a rope.

“Glenn Exum didn’t use a rope on the first ascent,” his partner, Joe Hawkes, had argued the night before, his angular face twitching in the firelight. “Paul Petzoldt didn’t either, on the second. Climbed it right after him, the same day—handed off his clients to Glenn on the descent and practically ran up the route. And that was seven years ago!”

Perhaps it had been the second bottle of beer that had convinced John of Joe’s logic. Maybe it was the warm blanket of dancing flames that had befuddled his thinking. Whatever the reason, they’d left the rope behind in Grand Teton National Park’s Jenny Lake Campground at six that morning—and now, five hours, seven miles and more than five and a half thousand vertical feet later, Joe was somewhere above, having climbed out of sight, and John was nervously eyeing the terrain ahead of him, wishing they’d brought a rope.

Son of a bitch, John muttered to himself. His fingers were starting to sweat.

He blinked, searching for another hold, but all he could see was the nubbin.

The speckled stone all around him was coarse and warm from the sun. John had rolled the sleeves of his white cotton shirt past his elbows, but even with the light breeze blowing in from the west, he could still feel the sweat on his back soaking into his canvas rucksack as he studied the rock for clues.

All around him, bands of feldspar and quartz arced and swirled in interlocking patterns of tawny-colored rock, rough as a lion’s tongue after two billion years of metamorphosis. Zebra stripes of white and black silicate alternated with waves of bronze. It was like climbing in a cosmos of foliated granite.

He was glad he’d warn his kletterschuhes; the tricouni nails of his climbing boots would have skittered around on the rock like metal on glass.

Maybe there was a feature he’d missed; maybe there was an edge for his foot hiding somewhere on the wall.

He blinked, stared. There wasn’t.

John looked up. Joe had moved through this section so easily John hadn’t paid attention. Now he was nowhere to be seen, and the Grand’s summit lay out of sight, too, hundreds of feet above.

How long had he been stuck here without moving? Thirty seconds? A minute?

Maybe longer. Cumulus clouds decorated the sky in long gauzy trains, running their suspended outlines over the plains and peaks to the east in lazy shadows.

He didn’t know if he could do this.

Keep going, a voice within him said, so softly it could have been the wind.

John pressed his right palm to the weathered, textured matrix of golden stone for balance, then stretched left for the nubbin, pinching it between his fingers. With no other holds for purchase, he slowly raised his left foot up to the level of his hand. Ever so delicately, he straightened, shifting right, pressing against the wall to maintain equilibrium until he was standing. His right foot was pasted to nothing, but he was centered, upright.

Black and gray mica. Rounded waves of white. Stripes and striations, bands and belts, golden kaleidoscopes of warped and wavy crystals. The definition was shocking.

He would never be able to reverse the move he’d just made.

The premise of Ninety-Pound Rucksack is that we’re not only telling the story of the 10th Mountain Division; we’re exploring the origins of outdoor recreation in America as well. John McCown offers insights into both, in part by helping to illustrate who was climbing and skiing before the war.

On the day he found himself so delicately positioned on the Exum Ridge, John’s love of the outdoors was about to go through an exponential leap. The Exum Ridge was not only the Grand’s most famous route; it was the first real climbing route John had ever been on. For most people, even today, the exertion necessary to climb the Grand in a twenty-four-hour period is enough to shift one’s perspective. Though John had left the Valley floor that morning, he’d been engaged in the technical rock-climbing sections of the route for barely an hour when he found himself balanced atop one of the signature moves on a signature section of the route called the Friction Pitch that is devoid of incut holds. Years of athletics had quickened John’s response times, but nothing had prepared him for the mind-altering move off the nubbin.

The man who had left camp that morning without a rope was young and vigorous, a bystander to the world unfolding before him because he knew no other way. The man who would return to it later that day would no longer be a bystander. In his next few moves off the nubbin, John would brush up against a previously unknown dimension wherein his own actions determined which side of the line between life and death he would inhabit. Never before had he imagined a situation that was both so mesmerizing and terrible in its allure, and he instantly wanted more—and that would have implications not only for him, but for the 10th Mountain Division, the US Army’s assault on Hitler’s Gothic Line and the outcome of World War II in Europe.

Six-foot-two and square-jawed, with broad shoulders, olive skin and dark hair, John had been born on the Fourth of July in 1918 in Washington, DC. His father, Andrew, was a prominent corporate lawyer in Philadelphia; his mother, Mary, came from successful entrepreneurs on both sides of the family. Her parents had built a family summer camp near Dingman’s Ferry in the Poconos, where Andrew, an active sportsman, had instilled his love for the outdoors in his four sons as he taught them to hunt, fish, backpack and camp.

John was the oldest. He was whip-smart, mischievous, funny, and bow-legged, which saved him from being a cliché, because he was also good-looking. He was the sort of strapping young man who, from the outside, seemed both charmed and charming. But as with all people, John’s outward appearance offered little insight into his inner workings, and they were troubled, as most peoples are, by the circumstances he couldn’t control.

John and his brothers, Grove, Dick and Andrew, had been raised in a big house in Germantown, Pennsylvania, a well-to-do suburb in the northwest corner of Philadelphia. They’d all attended private schools, first Germantown Academy and then William Penn Charter, and John had run track and played baseball and football and lacrosse until the sports had fleshed out his frame. He was a good student, polite and considerate with his parents and strangers alike, and an affectionate teacher had taught him and Grove to ski on winter vacations in New Hampshire. Natural athletes both, they took to the sport with ease—but it was a chance encounter with falconry that had caught John’s heart, and that had come to define his teenage years.

Andrew, the youngest in the McCown family household, was five years John’s junior. Grove, the second oldest, and Dick, the middle child, were physically and intellectually gifted, though not as much as John was, and they shared a love of similar things—the sports and the hunting and the camping and even the singing, which they’d inherited from their father, a 1st tenor with the Orpheus Club of Philadelphia.

But not Andrew. He didn’t have the stamina. He loved butterflies, and their father had given him a Winchester .22 pump rifle for his twelfth birthday, but he didn’t have the heart to shoot the squirrels and crows and turkeys the way his brothers did, so John, who was sweeter on Andrew than anyone else in the family, taught him to hawk, the way his high school teacher had taught him, holding Andrew’s arm up while the raptors learned to feed from his hand. But hawking exhausted Andrew. Everything had, since he’d developed leukemia.

Their father had made it clear to the boys that he expected them to follow him into the family practice. Not Andrew, of course. Andrew was too ill for dreams. But Dick, Grove, and John most of all, had had their lives set out for them by their father, and they’d done as he’d decreed. Following William Penn, John had gone to the University of Pennsylvania, where he was currently studying at the Wharton School. Law school was next. It was the family way.

Except John didn’t want to study law, and he didn’t want to work in his father’s firm. From an early age, he’d loved the outdoors most of all, scrambling around on cliffs in the Poconos and losing himself in the forts and fantasy fights he’d concocted for him and his brothers to play. Falconry had accelerated that love in a way so fierce it made his breathing thin, and soon all he’d wanted to do was climb trees in search of nests. He’d brought Grove along with him, and they’d practiced shimmying down the side of their house in Germantown with a hemp rope, then telling Dick and Andrew about their adventures after their parents had gone to bed. Being outside, particularly with his birds, offered John an escape that had become like an addiction. He wanted to be free like them, beautiful, flawless, soaring high above his father’s expectations and Andrew’s illness with effortless maneuverability and quick bursts of speed. But he didn’t know how to be free, and so every day he returned to the ordinary rhythms of school and sport and family as one returns to waking from a dream.

And then on July 27, 1938, Andrew died. He was 14. Their parents didn’t speak of his death, just as they had never spoken of his illness. Lacking a vocabulary with which to discuss their loss, the boys didn’t either. John retreated into his falconry and the outdoors, which offered both catharsis and an escape from the life he had been groomed to inherit.

This summer trip out west had been his parents’ idea: give the boys some space, let them hunt and fish and breathe in the wide western landscape until the fog that had enveloped them broke apart. With John’s Cooper’s Hawk hooded and perched atop a bar across the back seat of their 1937 Ford Woody Wagon, he and Grove, two years his junior and five inches shorter, had left Germantown on June 19 with their brother Dick, who was 16 and shared their dark skin, dark hair, athletic frame and bow-legged stance. They’d headed west, through West Virginia and Illinois and Missouri, stopping for repairs when a pin dropped out of the drive shaft (twice) and sleeping in the back of the car. On June 21, in Hannibal, Missouri after regaling onlookers at the Ford Dealership with his hawk, John was invited to give a speech about it at the Lions Club. On June 22, car fixed, they drove 570 miles in a push and camped on the side of the road outside of Denver. John bought a black Stetson hat with a two and a half inch brim for $7.50. The next day, they dropped Dick off at a summer camp for boys in Estes Park, Colorado, then continued north, through the high summits of the Rocky mountains, still blanketed with snow and more magnificent than anything they’d ever seen, toward the Tetons, where they planned to spend three or four days with a family friend before heading on for the trip’s ultimate objective, Washington’s Mt. Baker.

They’d come to ski, something they’d figured would be in abundant supply among the snowy summits of the west. They’d fallen in love with speed during their winter holidays in New Hampshire, and when John found an article on summertime skiing on Mt. Baker’s glaciers, there was nothing that could dissuade them from their goal. But as they were driving out of Jackson’s Hole up Teton Pass to continue west, they were pulled over by Fred Brown, six feet tall and slim almost to the point of frailty, who’d noticed the skis on top of their car when they’d driven past his house and roared up from behind to cut them off. Did they know about the second annual Fourth of July ski race taking place the next day in Paintbrush Canyon, deep in the Park? They’d looked at each other, then at the man with the bright blue eyes that bulged from behind wire-rimmed glasses who was bending over to interrogate them through the window of their own car. They didn’t. Brown, who they’d soon learn was Grand Teton National Park’s ski operator, Wyoming State Ski Champion and an indefatigable promoter of all things skiing, insisted they stay at his house that night and compete in the race the next day—which happened to coincide with John’s 21st birthday.

How do I know all this? Because John’s niece, Grove’s daughter, Susan McCown, shared with me the letters that the brothers wrote almost every day, all summer long, to their parents. The letters paint a portrait of two endearing young men who are falling increasingly in love with the mountains—and, as we shall soon see, with climbing.

And yet, even as I pored over their letters and cross-referenced them with details gleaned from conversations with Fred’s son and email exchanges with his protégé and newspaper clippings and park reports and Teton summit register entries from the climbing season, it seemed strange to me that in the summer of 1939—just a few short months before the Soviet Union invaded Finland and launched the Winter War—a ski race was being held in Grand Teton National Park on the 4th of July. It seemed stranger still that early that morning, John and Grove were joined by fifty other skiers, cowboys and cowgirls for the six-mile hike into Paintbrush Canyon’s Holly Lake below the southwest slopes of 11,555-foot Mt. Woodring, where the race was to occur.

For one thing, skiing and summer vacations take money. In America, as the post-WWI economic boom of the roaring twenties led to the wide-spread adoption of the automobile and the expansion of train routes throughout the country, people had turned to recreation as a way to spend their money, and the wealthy in particular had become enamored of skiing—but then, in October 1929, the stock market collapsed, and a decade of economic calamity ensued.

I knew how John and Grove had managed to make their way to the Tetons: they were rich. But what about the four dozen other people who were following Fred, the pied piper of Teton skiing, into the hills?

By 1933, when the Great Depression reached its nadir, nearly half the country’s banks had failed and some 15 million Americans—a quarter of the working-age population—were out of a job. Even those lucky enough to keep theirs were up against it, as wage income fell more than 42% between 1929 and 1933.

In the 100 days following his March 1933 inauguration, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration had reformed the financial system, passed legislation that created jobs, stabilized industrial and agricultural production, and begun to stimulate the nation’s economic recovery. Over the next three years, the Gross Domestic Product had grown at an average rate of 9 percent per year—but in 1937, another economic depression wiped out much of the previous gains, and though the economy had begun to improve by the time the McCowns reached the Tetons, the country was by no means out of the economic woods.

For another thing, Jackson, Wyoming, population 1,000 in 1939, was geographically isolated. Tucked away in Wyoming’s northwestern corner, the mountain hamlet wasn’t reachable by rail, and even reaching it by car in the 1930s required a level of commitment difficult to imagine by today’s standards. In 1929, the year Grand Teton National Park was established, 51,500 people visited the area. By 1938, despite the Great Depression, that number had swollen to 153,353. It dipped to 87,133 the summer the McCowns arrived as the economy shuddered, but was back on the upswing by 1940, when 103,324 people visited the Park.

Are those big numbers, or small numbers? Were the only people marching up Paintbrush Canyon to have a go at Fred Brown’s hairbrained race members of America’s upper class?

No. There was enough socioeconomic diversity in their ranks to illustrate that in America at the end of the 1930s, it was more than just the wealthy who enjoyed the mountains.

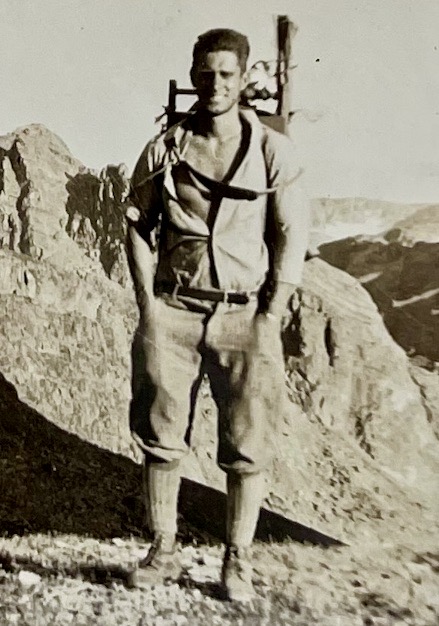

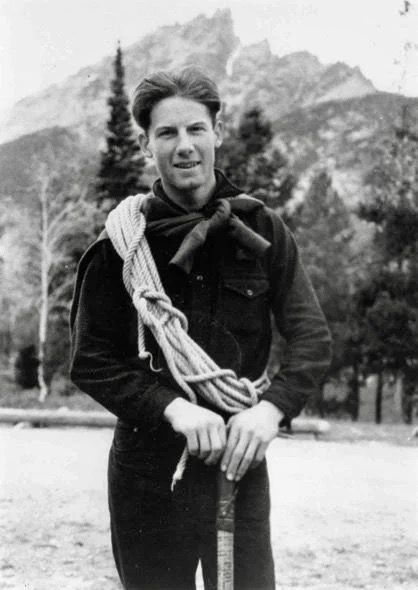

Among the party was Fred Brown’s best friend, a twenty-nine-year old, bushy eyebrowed ox of a man named Paul Petzoldt. Charismatic, with a booming voice and a bear-paw grip, Petzoldt had pale blue eyes, a thatch of dense brown hair and enough character flaws to satisfy a Greek playwright.

By 1939, Petoldt’s exploits as both a climber and a personality were already legendary. His first attempt on the Grand in 1924 as a sixteen-year-old farmboy from Twin Falls, Idaho, had ended in near-calamity when he and his childhood friend, the nineteen-year-old Ralph Herron, had attempted the mountain’s longest feature, the still-unclimbed east ridge, in cowboy boots and bib-top overalls with only a lasso rope and a pocketknife for equipment. Both had come in handy the next morning when they’d rappelled into, and then cut their way out of, an iced-up chimney they’d hoped would provide an escape from the storm that had left them buried in snow and ice overnight. Too embarrassed to return to town without a summit, they’d managed to work their way around the mountain and climb it by its route of first ascent. Back in town, they were hailed as heroes, and Petzoldt had become the range’s de facto guide when he took three parties of locals up the mountain over the next month.

The following summer, he’d become its de facto rescuer when he caught Herron’s fall with a lasso rope on the same east ridge, then carried him off the mountain on his back. A week later, he oversaw the range’s first body recovery when he retrieved Theodore Teepe from the glacier at the base of the Grand that now bears his name.

Petzoldt had made the first winter ascent of the Grand Teton in December 1935 with his brother Eldon and Fred Brown. The following summer, he’d made the first ascent of the Grand’s north face—the most fearsome alpine wall in the United States. He’d perfected the concept of layering after discovering the perils of cotton and the merits of wool the hard way, and he’d developed a form of mountain communication using short, distinct words— “On belay, up rope, slack, climbing”—that persists to this day. He’d also established the foundations of American mountain guiding with his Petzoldt School of Mountaineering, which actually taught clients how to climb—a direct repudiation of the European model and its focus on roping clients up and down a mountain without so much as a discussion of the how or the where or the why.

All of Petzoldt’s skills would be put to good use in 1942 when he joined the 10th Mountain Division at Camp Hale and was put in charge of developing its mountain rescue system.

Had Petzoldt simply been the sum of all the good he brought to the world, his reputation would have been sterling. Such was not the case, for Paul Petzoldt contained multitudes.

In 1938, Petzoldt had been invited by Charlie Houston to join him, Bob Bates, Bill House, Richard Burdsall, and Norman Streatfeild for the First American Karakoram Expedition to the 28,251-foot K2, the world’s second-highest peak.

Oh, to have been a fly on the wall on that expedition. Bates and Houston were part of the “Harvard Five,” who, as we discussed in the last episode, were the group of young Americans that included H. Adams Carter, Terry Moore and Brad Washburn who had helped advance the standards of mountaineering in the 1930s. Though Petzoldt had spent the summer of 1934 at Windsor Castle as a guest of one of his climbing clients, the private chaplain of the King and Queen of England, and dined with Fred Astaire and the Prince of Wales, he hadn’t finished college, and even in the ostensibly classless America, the tension between the elite and the commoner must have been palpable.

Despite their social differences, the team worked well together. Greatly benefited by Petzoldt’s experiences in both the Tetons and with piton craft, to say nothing of his ample energies, they managed a successful reconnaissance of the mountain. With Houston, Petzoldt ascended to the team’s highest point, at around 26,000 feet, then continued to climb after Houston, exhausted, lay down to rest in the sun. Petzoldt reached a point 2,200 feet below the summit, higher than anyone had ever been.

Post-climb, things got interesting. The affluent members of the team hired a bus and driver and made a tour of the journey home, driving from Rawalpindi to Afghanistan to Iran en route. Lacking his companions’ financial latitude, and curious about Eastern religions, Petzoldt decided to travel to India, where he eventually fell in with a Dr. and Mrs. Johnson, two American ex-patriots who had joined a charismatic guru in his commune. Petzoldt’s first wife, Bernice (he would go on to have three others), traveled to India to join her husband. Mrs. Johnson poisoned her food. Beatrice stopped eating and, a few days later, recovered. Petzoldt went to get a meal for his now-ravenous wife. When Mrs. Johnson found out that the meal was intended for Beatrice, she demanded Petzoldt give it to her so she could take it to Beatrice herself. Petzoldt demurred. Mrs. Johnson grabbed a gun. Petzoldt bolted for the courtyard and ran smack into Dr. Johnson, killing him. Though Petzoldt was eventually acquitted of manslaughter, he exited the country using funds pulled together by Houston and Bates, who never saw the money again.

(In 1940, there was a reunion of sorts of the K2 expedition in the Tetons when Bates, House and Petzoldt climbed the north ridge of the Grand and the north ridge of Moran. This indicates they must not have been too crosswise with one another; but in 1997, at an American Alpine Club annual dinner, I sat beside Bob and his wife, Gale. For the entire evening, they told me the story of the 1938 K2 expedition. More accurately, they told me the story of Paul and the missing funds. Sixty years after the fact, they were still pissed.)

Petzoldt was a force of nature. He was complicated, suffering bouts of periodic depression that caused him to disappear from time to time and launching and losing countless businesses over the course of his long career with business practices that would have made a former president blush.

But Petzoldt was scrappy. Lacking the financial safety net of his Ivy League partners, he hustled out of necessity.

Petzoldt was first and foremost a climber, but he could also ski. He had to. The ferociously cold and snowy winters of Jackson’s Hole—as the valley, named for fur trapper and explorer Davey Jackson, was known—lasted from the end of October until May, leaving 200 to 300 inches on the valley floor and 500 inches higher in the mountains. Fur trappers had been using rudimentary wooden planks to navigate the valley in winter as early as the 1860s, and for the hardy souls who, starting in the late 1890s, called the place their year-round home, skiing was both transportation (roads were not plowed regularly until the mid-1930s) and one of the only diversions from cabin fever. Though Fred had pioneered ski touring in the Tetons in the early 1930s, intrepid skiers had been making journeys to and from town for years, from as far away as the outlying settlements of Moose and Moran—distances of twenty and forty miles respectively. Hell, in early December 1935, Paul and Bernice had skied 70 miles from Ashton, Idaho over Teton Pass to a dude ranch they’d been hired to manage in Moran during a blizzard. The seventy-mile journey had taken them seven days.

Here’s what Petzoldt had to say about skiing in the 1930s.

“I had not been a skier in my youth, because there’s not much snow on the lava beds of Twin Falls, Idaho. At that time, adventure skiing or skiing for fun was practically unknown. Of course, in those days, you’d have been criticized for doing anything for fun because you weren’t supposed to have fun, you were supposed to be working. You had to produce something—bring back some wood or go out to herd cattle or something. But you didn’t go out there to have fun. That was against the ethics of the day.

“But we did. We did.”

Jackson was a hardscrabble ranching community in the 1930s, and like many of its residents, Petzoldt didn’t have a lot of money, but he had heaps of mountain smarts and ingenuity, and he applied it to skiing.

“We were experimenting with skis, we were making ski wax out of honey and tar and lard and coal dust, trying to get something on skis that we could put on whenever the weather changed so they would either glide like wind over water or they would stick without sliding back so we could climb up the hill with them. So I learned how to ski, and we experimented with the old type of skis that we made ourselves from pieces of lodgepole pine, where we split the logs down the grain and then sawed them off so that we had long boards that looked like skis, and then we boiled them in water for a while and bent them up on the ends and held up there till they dried so we had an upper end. And then in those days, we could find some old belts from washing machines that were very sturdy, and we could put those on there, so we could put our feet in [the bindings] and bundle up [our feet] in the wintertime, so they were very warm. And we could get a long pole made out of lodgepole pine again that was strong and limber, and we would use that to pull to push our way along on the skis—it was like paddling. We reached out with the pole, and put it in the snow, and you rode down through the snow, and the skis were long, so they would stay up on top of the snow—because people didn’t have the mechanical means of building ski trails like they do now.“

I knew that not everyone in the 1930s was making their own skis out of boiled wooden planks and their bindings out of rubber gaskets, but I was still unclear on the socioeconomic factors at play during the depression or how they affected the state of American skiing. So I did what any curious skier doing a podcast on the skiers and climbers of the 10th Mountain Division would do: I called Dr. E. John B. Allen, an 89-year-old professor emeritus of history at New Hampshire’s Plymouth State University and the author of the book From Skisport to Skiing: One Hundred Years of an American Sport, 1840–1940.

And because we want this episode of the podcast to provide a solid foundation for our examination of the ways the 10th contributed to the evolution of outdoor recreation in America, I asked Dr. Allen to start from the beginning.

[Dr. John Allen Interview]

A trailer for Arnold Fanck’s ski film Sonne über dem Arlberg, starring Hannes Schneider. The spread of Schneider’s Arlberg technique was aided by his appearance in a dozen ski films, the most important of which was Fanck and Schneider’s first collaboration, “Das Wunder des Schneeschuhs” (“The Wonder of Snowshoes”).

Dr. Allen tells me that prior to the advent of skiing in the country, outdoor recreation in the winter was limited to three things:

“Snowshoeing, tobogganing and skating. The first time that Americans in the lower 48 see ski tracks is 1841 in Beloit, Michigan.”

In its earliest incarnations, skiing was used primarily for utilitarian purposes such as travel, hunting and delivering the mail.

But then, in the early 1800s, a massive wave of imigration began that would have profound implications for the sport. Between 1820 and 1920, more than 2 million Scandanavians came to America. More than 100,000 arrived in 1882 alone. They settled primarily in the midwest, and brought their traditional mode of travel with them.

“The huge numbers of Scandinavian, particularly Norwegian immigrants, appear in the 1880s, 90s right up through to the First World War. And that is exactly the same time when Fridjof Nansen crossed the lower half of Greenland—the actual crossing was 1888, but his book about it came out in 1890. So just as he was describing a kind of leftover Christian healthy outdoors activity that would better body [and] soul—not only just of himself, but people that he met, even to the extent of having an effect on local village, local town, even local country—you have these thousands of immigrants coming over. When they strap on skis, they don’t think in terms of Christian nationalism, but they do think in terms of health and enjoyment of the outdoors—and this comes just at the same time that America is going through one of its great industrial pushes.”

The sort of skiing that Petzoldt and Brown liked to do and that the McCown brothers would soon come to love was not, by and large, a mechanized form of skiing. It was instead the kind of skiing that backcountry skiers enjoy today: ascending and descending under one’s own power, with little to interrupt the connection with the natural world. It’s hard to find the right words in English for this sort of skiing, where the exertion of the body leads to a settling of the mind. So when I heard Dr. Allen talk about a concept first described by Nansen that lay at the heart of America’s earliest chapter of skiing, I lit up, because it’s the essence of the skiing the soldiers of the 10th would later learn to do.

“The Norwegians have a term which has no equivalent in English; the actual term in skiing is “Ski Idraet.” And it’s always translated as “sport.” But back then we just didn’t have the word “sport.” Sport only comes when you’ve got organization and when you’ve got records to be broken and records to be made. And it comes to mean, let’s say, around 1900, that it is a foundation for a strong national country. And this is very important where Norway is concerned because it’s been under the overlordship of Sweden for 100 years. Norwegian independence took place in 1905—precisely as Idraet was in full swing, just as these masses of not just hundreds of immigrants, but thousands of immigrants were coming over. As far as nationalism was concerned, it was extremely important because here was a new country [Norway], and this new country had eternal snow. And there was a real romantic connection between the nationalism of Norway and the actual political success of the state. And Nansen was the person who really described it best of all. He talked a bit in terms of wiping the soul clean, getting out into nature and God’s great universe and making all of it something for yourself as a better person which would then affect kith, kin, village, town. And indeed, as he said, it is something that is perhaps really important wherever national psyche is concerned.”

In America at the turn of the century, Norwegian quickly became the lingua franca of the pursuit.

“It was very much a club activity. And that club activity was run basically by Norwegian immigrants. In many ways you had to go along with the Norwegian styles of skiing, the Norwegian way of measuring jumps; the general sort of aspect of being was more or less entirely Norwegian. The US National Ski Association was founded in Ishpeming, which is in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, in 1905. And they immediately started a magazine—and what was it called? Ski Idraet. I can remember reading a fairly long article in Ski Idraet. It was in Norwegian. There were two lines at the bottom: “These are the rules of jumping, and they will be obeyed.” That was in English.”

There were two kinds of Norwegian skiing: cross country, and jumping. In America, one quickly eclipsed the other in terms of popularity.

“In Norway, even in the late 19th century, the idea was that a good skier was an all-round skier. The Norwegians had a major meet at Holmenkollen, and until 1933, a man who wanted to enter the competition had to do both cross-country and jumping. It was only in 1933 that they were allowed if they were a jumping specialist just to jump in the competition and didn’t have to worry about cross-country racing.

“But what happened in the United States was that jumping became a real crowd puller. I would almost say that in the Midwest, ski jumping almost turned skiing into a spectator sport. When there was a jump, trains would come into some little town of maybe 1000; people would suddenly have an influx of 8000 people coming to watch maybe 16 jumpers. And that sort of attitude also produces professionalism. And one of the things about Ski Idraet was it was supposed to be so pure, so unprofessional, so full of godliness rather than money. Increasingly, the people in charge of Norwegian skiing out there in the National Ski Association had to realize that there were enough people around to have a professional class as well as boys’ classes and men’s classes and so on.”

Ski jumping’s popularity had profound implications for cross-country skiing.

“And it almost failed over here. I have read a number of reports where it says things like the Finn boys finish, the Finn boys are going to run a race. Anybody that wants to can join and if you want to use two sticks, you can—the Norwegian way was to have one stick, or pole, that is—and then this sort of result would be that the race attracted 10 people. And the winner was expected to be some local guy, but he’d been in the United States too long and had just grown fat. So he was red in the face, you know, is sort of what happened. And when you look at the statistics for national championships, in one particular year, probably 1915, 1916, 1917, somewhere around about there, there were no takers for a national championship in cross country skiing.”

On June 8, 1914, a Serbian nationalist assassinated Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife while they were in Sarajevo, Bosnia, which was then part of AustriaHungary. Within two months, Europe found itself embroiled in the first world war—which had implications for both the future of ski troops and the future of skiing.

“During that war, there had been a fair amount of action in a comparatively few places. One of the places was the Italian front, in the Dolomites. Ski troops and ski trooping after the war gave skiing a sort of foundation in one sense. In another sense, there was a real foundation, particularly among the Austrians and the Germans, because realizing that the Italian front was (a) in the mountains and (b) much of the difficulty occurred during the winter, there was a decision to boost the mountain troops.”

Austria did more than simply boost its troops. Thanks to one man operating out of the country’s Arlberg mountains, it midwifed the birth of a technique that, once the war was over, would change skiing forever.

“One of the reasons why skiing took off in the 1920s was largely because of the success one particular man, Hannes Schneider, had teaching troops how to ski on the Italian front. He and his mentor, they would take a group of men—let’s say 40 men—teach them how to ski, meaning really not ski fast or anything but ski steadily, and be able to do marches on skis and climb on skis, herringbone, and so on. And at the end of that, they would keep maybe three or four ones who had done rather well and turn them into instructors. So what actually Schneider was doing during the war was providing a form of instruction, which made for a form of skiing, which made for the growth of skiing after the war, because he applied his military way of skiing to civilians.

“Schneider was one of the earliest people who seem to recognize that “speed is the lure.” By, let’s say, 1922, the techniques that he had produced, which became known almost instantly as the Arlberg technique, was both a way to teach, a way to learn and finally a way to ski. And it was rather different from the way Norwegians skied. The Norwegians came down their hills in rather swift telemark turns; Schneider came down his hills with a low crouch and a lift and swing into the turn, one turn after the other, with a fair amount of speed attached to it. And it is at that sort of moment that you begin to get the real divergence between Nordic—because it wasn’t called Nordic skiing, there was only skiing— but you begin to get the divergence between the way that the Norwegians skied and the way that Schneider skied.

“After the First World War, there was a competition to win the peace, as the French said, and to win the peace really meant getting tourists there. And so what happened to ski schools? One of two things. The one thing was that the Arlberg became so ubiquitous and so admired that, as the London Times said, at one stage, “it seems to be impossible to tamper with it”. It was The Word, largely because it was also made a requirement for school education teachers in the land of Tyrol in the various sections of Austria. And then with Germans from the south, it became the way to ski. There was an Arlberg school in Paris, there was an Arlberg school in London, and when some instructors from Hannes Schneider’s ski school came over to New Hampshire, you find Benno Rybizka, who was one of his leading instructors, managing the American branch of the Hannes Schneider’s ski school in North Conway.

“Into that mix comes probably the more important person. And this is Arnold Lunn, who was really a mountaineer before he got hurt, and who made a couple of places in Switzerland a sort of Rock of Gibraltar, sort of a British enclave. And he liked the idea of mountains very much. He was a lover of mountains.

“What he found was that if you climbed up a mountain, you of course left your valley floor, which was farmland, then you walked through the woods and up you went. And then you came to tree line, and then the top was open for another 1000 feet or however much. So mountaineers climbing up would have to have two sorts of skiing. In order to get to the bottom again, one would be the down-mountain skiing—what used to be called the straight race—so that the top of the mountain to the tree line was one sort of skiing; but then you had what he called tricky tree running. And in order to make that possible for practice, what you do is you get a hill, put some branches in the way and make up what became called a slalom—”lom” in Norwegian means a track and “slal” is going around obstacles. It was all done to kind of bring the level of skiing up to a certain stage where you could enjoy yourself in mountains, and he promoted this increasingly in the early 1920s.”

In the 1920s, thanks to Arnold Lunn’s races and Hannes Schneider’s techniques, alpine skiing became increasingly popular in Europe. As Austrian instructors versed in the Arlberg school came to America to teach, the Nordic dominance of skiing in this country began to be displaced.

Other factors were at play as well. The Dartmouth Outing Club had been formed in 1909 by Fred Harris, a student who by his own account had “skeeing on the brain”. As the DOC developed, it became the focus of collegiate skiing in America, creating a model that other universities could and did emulate, and connecting the sport to the affluent and elite in the process.

“The outdoors was part of a possibility for the educated. However, what Fred Harris did and what the Dartmouth Outing Club did was to provide a framework which could be easily copied, and indeed was copied. UNH, Middlebury, Williams and Yale, Harvard, Cornell—you know, this is the Ivy League stuff, or if not Ivy League very near Ivy League stuff.”

The DOC organized the country’s first downhill and slalom races in the mid- to late 1920s. As Dartmouth held, and won, more and more such races, it influenced the National Ski Association to sanction them for the first time, further disrupting nordic preeminence. By the early 1930s, the college had become the unparalleled leader in American skiing.

“Alpine racing became increasingly important in the winter circuit. And who won all the Alpine races? Basically Dartmouth. So it becomes very influential.”

There was another club that played an important role in the alpine skiing invasion. The Appalachian Mountain Club, which was headquartered in Boston, had been established in 1876 to promote exploration and conservation of nearby wilderness areas and, in particular, the pristine White Mountains of New Hampshire. It, too, was a club for the well-to-do, who, as economic prosperity swept the country in the 1920s, vacationed in the Alps on winter holidays.

In 1928, AMC member Wilhelmine Wright travelled to Kitzbuhel, Austria, where she was introduced to the Arlberg technique first hand. Upon her return, she wrote an article on Alpine skiing in Appalachia, the AMC’s publication, that began to socialize the method amongst its membership. That same year, the AMC began offering club instruction, and brought Otto Schneibs, a German-born skier and the author of several influential books on the topic, to teach its members to ski. Cost: $.25/hour, for a two-hour lesson. The Arlberg technique began to catch fire throughout the east coast. In 1930, when Schneibs was hired by Dartmouth College as the coach of its ski team and propelled the college to the vanguard of American skiing, that fire began to burn hotter.

The stage was set for an explosion in American skiing. As the equipment from the 1920s began to improve to accommodate Alpine skiing, a more sophisticated ski with steel edges appeared on the scene, accompanied by tighter bindings and stiffer boots. Ski clubs that doubled as social clubs sprung up, helping to establish a tone for the increasingly popular sport.

And that tone had a decided German accent.

World War I had made the US the world’s banker, and when America sneezed, the world caught a cold. As the October 1929 stock market crash plunged the country into an economic tailspin, the ripple effect engulfed Europe. Mass unemployment, hyperinflation, the collapse of industrial output and trade, bank closures, and mass poverty led to increasingly turbulent domestic politics—including, as we discussed in our last episode, the rise of Hitler and the Nazis.

For those appalled by the racist, totalitarian fascism that defined the party, and for Jews in particular, the writing was on the wall: get out of Europe if and while you still could. The resulting exodus included Alpine skiers, instructors and mountaineers, who arrived in America to escape Hitler’s malignant nationalism.

Hannes Schneider was one of them. An outspoken critic of the Nazis, Schneider had been stripped of his ski school and imprisoned following the Anschluss, as Germany’s 1938 annexation of Austria is known. A masterclass in international relations not only managed to free Schneider from house arrest, but to bring him to North Conway, New Hampshire, where he re-opened his ski school to American clients.

Hitler’s loss was America’s gain. Not only would Schneider go on to teach the Arlberg technique to Americans out of North Conway for another fifteen years; he would also go on to teach it to the soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division, in which his son Herbert would serve, as well.

As the Arlberg technique flourished around the country, the German language became synonymous with skiing, displacing Norwegian as the sport’s mother tongue.

Schneider had imbued his method of teaching with military precision, and the German and Austrian instructors who taught it to Americans beat the same regimented approach into their students, but their Teutonic rigor did nothing to diminish the sport’s growing popularity.

Neither did the depression. In fact, it became instrumental to skiing’s growth. Fiscal policies enacted by President Roosevelt helped to lay the sport’s infrastructural foundation. The Civilian Conservation Corps went to work building ski trails in the East. In the West, where much of the desirable ski terrain lay on public lands, chambers of commerce lobbied the federal government to open them to skiing and to underwrite the costs of development. As the revenue generated by skiing justified the expenditures necessary to keep roads open, winter snow removal took place in smaller, more remote communities for the first time.

Despite, or because of the depression, the business of skiing began to boom.

[Paul Petzoldt:] “But the real reason the skiers were starting was that the railroads wanted to get more passengers on their trains.”

How much do I love these ski trains? Let me count the ways. First, the people getting on them sometimes didn’t even know where they were going.

“People had carried their skis on the trains way before 1931. But the snow train era begins largely as a result of a couple of people in the AMC and the Dartmouth Outing Club of Boston who have had experience on snow trains in Germany. They’d been there, and they’d seen this happening. And then they say, well, why can’t we do this in Boston? And so they get the ear of people in the Boston and Maoine [Railroad] who are looking very desperately to keep alive during the Depression. And then in January 1931, 197 people get onto the train in Boston, and they go to a place called Warner, New Hampshire. The natives of Warner don’t like these people wandering around on our gardens. They look funny. They don’t talk like we do. They don’t like it. Three weeks later, 923 people got out at Epping, New Hampshire. Epping is a flat as you can imagine. The Ladies Aid Society was there, the Boy Scouts were there, the churches were opened, the women were providing lunches, taxi drivers were there, their farmers were there with their carts and horses and everybody had a wonderful time. New Hampshire had found a new winter business.”

Second, the passengers didn’t even necessarily know how to ski… or, for that matter, have their own ski equipment or clothing.

“Two or three people who were the organizers—they came from the AMC and the Dartmouth Outing Club—they had weather people dotted around in the various stations. Frequently they were station masters of odd little towns, and then they’d be sent indications of what the snow depth was, and so on and so forth. But what it meant was that these two or three people sitting around just said, well, this week, let’s go to Canaan. And it didn’t matter at all that the person on the train knew they were going to Canaan. In fact, they probably didn’t even know the name. Because the train would go to Canaan, stop there and be the lodge, as it were: a place where you left your clothes, you left your picnic. When you needed to rest, you came back and sat in your seat. You had to make sure that you got on the train when it went back, that’s the only thing that really was vital.

“Certain of the clubs would have actual instructors on the train. And the instructor would sort of gather his group and take them off when they arrived at the particular destination. It became so sophisticated that a couple of shops used to have a train car literally for renting all equipment, and all clothing. You could walk onto the train in your suit, and by the time you got off, two hours later, you could be outfitted with skis, boots, poles and clothing.”

Third, the ski trains’ new clientele began to alter the socioeconomics of skiing.

“Sociologists would probably call them lower middle class. These are people who work in banks, tellers. These are people who perhaps are on the telephone exchanges. These are new to skiing people who make just about enough money so that they can spend the $2.10 it takes to get from Boston to, let’s say, to Plymouth, New Hampshire.”

Still, I struggled to understand the economics at play. In 1939, a stenographer’s average salary was $80 a month. Compare that with the costs of a five-day ski trip to Franconia, New Hampshire, one of the country’s skiing hot spots.

A pair of skis in 1939 cost $20. Bindings were $10; boots, $15; poles, $10; a ski hat, $2; parka, $9; ski pants, $11; socks, $3.50; mitts, $2.50. To get from Boston to Fanconia cost $4 for a round-trip ticket. Use of the ski tow cost $1, and admission to the ski area cost another $1. Food and lodging were $5 a day, or $15 for a five-night stay. Total cost: $142.

How were stenographers able to afford such a trip on their $80/month salary?

“They don’t do it. They go on the weekends, possibly only a one day or a lot of one day trains. They don’t take week vacations. The people who do take this sort of week vacation are the expensive types.”

The expensive types were the wealthy: the Dartmouth graduates, the members of the Appalachian Mountain Club, and the ranks of the exclusive ski clubs that sprang up in urban centers around the country—such as the Amateur Ski Club of NY, of which Minnie Dole was a member.

The Minnie Doles of the world were already skiing, so here’s another thing I love about the ski trains: the way they reached the new-to-skiing skiers was by promoting the ski-train outings as…

“Suntan Special. They used to run it. They’ve advertised this as the Suntan Special.”

Stuck in dreary Boston on yet another winter weekend? Rejoice: now you can jump on the ski train and get both a sun tan and a stem turn!

The ski trains became an overnight sensation. Twelve trains took 8,731 passengers out of Boston’s north station that very first season alone. From 1936-1940, the B&M delivered 174,622 ski passengers to their destinations. A new era had opened for New England skiing… and the idea quickly caught on.

“The success of the B&M was not lost on the New York to Haven and Hartford railroad out of New York City. In New York, out of Grand Central, the authorities had to cordon off the line for the ski trains. Because people came to watch these weird people carrying these boards, probably dressed in raccoon coats—they became a kind of New York sight to see. There were also lines out of Chicago. And also there were lines going out of San Francisco.”

And Washington DC. And Minneapolis. And Denver. To quote Dr. Allen from his book, “All across snow country in the mid-1930, trains took growing numbers of new skiers to a winter’s day away from office and bench.”

As the ranks of skiers grew from coast to coast, another innovation made the pursuit irresistible.

“The first one on the continent had been at Shorebridge Quebec and was basically copied at Woodstock in January of ‘34—and was an instant success. If you imagine skiing on a mountain, let’s say it’s a thousand feed: how many times do you walk up that? Once a day, twice a day if you’re young and healthy and so on, but it’s hard work.

“The moments that you get a rope tow, then all of a sudden, you ski an incredible amount more than you used to. To begin with, they were pretty primitive. And little by little they got fairly efficient, but as they got fairly efficient, other, more sophisticated lifts began to appear—first the J-bar and the T- bar—in the early days that was called he and she stick which shows how social skiing had become. And then you get the chairlift, the first one out in Sun Valley over Christmas of 1936, the second one in probably Laconia, New Hampshire in ‘38.”

By the time John and Grove McCown were making their way up Paintbrush Canyon, skiing had become the fastest growing recreational activity in America. The government had helped to fund the infrastructure. The trains had solved the riddle of transportation. The rope tows and chair lifts had made skiing convenient, social and fun. The first ski journalists had started covering skiing for national magazines, socializing the concept further. To quote again from Dr. Allen, “By 1940 Time magazine estimated the skiing population of the United States at one million. The Red Cross’s estimate was two million. Another authority put the figure at three million.”

All the elements of an explosion in American skiing were in place before the war . But then, of course, Hitler intervened.

At Fred Brown’s insistence, John and Grove had not only entered the 4th of July race that day in Grand Teton National Park; after the first heat, Grove was in first place, and John was in third. Now John watched from high on Mt. Woodring as his brother made the final turns of his second lap and double-poled across the finish line toward the high-altitude tarn of Holly Lake far below.

It was a stunning location for a ski race. Everything around John seemed to either plunge or soar. Holly Lake sparkled like a turquoise jewel in the glacially-carved cirque. To the south, the serrated ridgeline of Mt. St. John swept around to form the cirque’s western wall, its multiple summits stacked horizontally like the plates on a dragon’s back. Stone pyramids dotted snowfields and couloirs and gullies all around him. He tried to follow individual lines of rock and snow with his eyes, but each one led to another tower, another snowfield, another jagged edge or doglegging couloir or clean prow of rock that gouged the sky. The mountains seemed to reinforce themselves in repeating patterns, but the more he looked, the more he realized no two elements were the same.

Adding drama to the day, the cumulus clouds that had begun peppering the sky on their hike in were now cumulonimbus, dark and powerful, crowding the top of the canyon as they piled on top of one another like waves.

Fred had jabbed cottonwood saplings into the slope for gates, and they formed an irregular line down the mountain. The summer snow was firm and cupped and furrowed—nothing like what John had learned to ski on in New Hampshire. Tongues of it licked the lakeshore. He could see the upturned faces of the onlookers gathered around it as they watched from below, but, apart from Grove in his bright red Hawaiian shirt who was skiing up to Fred, and Fred, who looked like a beanpole even from where John stood, they were too far away to tell who was who.

A crack of thunder jolted John out of his reverie. He bent over and guided the toe of his leather boot into the metal toecup of his Kandahar bindings, pulled the steel cable tight around the heel, levered the coiled spring closed and repeated the process on the other side. He checked the cables one more time, straightened, then slid-stepped his way between the sapling starting gates.

Grove had stopped next to Fred and was doubled over, holding himself up with his ski poles and tilting his head to look back up the slope at John. Everyone seemed to be looking up at him. John thought that maybe he should yodel, but he didn’t know how.

The brothers’ parents had given them Otto Schniebs’ book, Modern Ski Technique, as a Christmas present the year before, and they’d pored over it until they could quote passages on techniques to one another with Germanic accents. It was hard to reconcile the black words and white pages with his surroundings now, though. Beyond Mt. St. John, the pyramidal summits of Teewinot, Mt. Owen and the Grand Teton were being swallowed by storm. What remained of their north faces was laced in spiderwebs of white. None of it seemed real.

John pushed off from between the gates in a tentative snowplow, then pulled his ridgetop hickory skis into a parallel Christie. As he picked up speed, he crouched lower into a powerful Arlberg squat the way the illustrated skiers had done in Schnieb’s book. The mountains soared at the periphery of his consciousness, thrusting their pointed tops into the black and roiling clouds, but all he noticed were the cupped ridges beneath his skis. He widened his stance to absorb them and shifted his weight to torque his skis into turns. He could feel the leather pressing down on the toenails of his downhill foot as he fought to complete each one.

The terrain came at him in a quickening rush of three dimensions. The snow was as corrugated as cardboard. He rotated the edge of his downhill ski out, then strained to bring the uphill ski parallel as he leaned his inside shoulder around another sapling. Gate after gate after gate flew by. Wet snow splashed from his edges. He registered the storm clouds blanketing the peaks around him in shadow, but they blurred in a flurry of speed as he willed his muscled frame to transfer what he wanted it to do through the steel shank of his boots, into his skis and onto the crenelated surface.

He released an outside knee, and a wake of snow plumed left. He shifted to the right; the plume shifted too. He fell into a bouncing, metronomic rhythm that buttered his transitions. Gravity loosened. John wasn’t a pretty skier, but he was strong, and he wrenched his skis from side to side in explosive, bounding turns.

The harder you go in the mountains, the greater the intensity becomes. As he peered down toward and through the gates below him, John’s perception seemed to deepen. The separation between calculation and movement shivered, then fell away. He could feel his legs burning, but it seemed to be happening outside his own body.

And then he hooked a sapling with a ski tip, spun sideways and tumbled to his hip.

Years of track and baseball and football and lacrosse had sharpened John’s reflexes. He popped back up without stopping and centered himself back over his skis. Holding his arms slightly out at his sides, he tucked his torso to lower his center of gravity—and hooked another gate. Down he went. He righted himself, but the rhythm was gone. He poled and kicked as hard as he could, and a few moments later glided through the sapling finish gates in a Nordic sprint.

He was panting. Blood pounded in his forehead as he turned and looked back up the slope. The… speed. The way his thoughts and turns had merged.

Was that what his falcons felt then they soared?

No. It was more than that. For the most fleeting of moments, it had seemed as if he were part of the mountain.

He’d never felt anything like it.

Fred ran up, laughing, and slapped him on the back. John could see Grove over Fred’s shoulder, struggling to release his skis from his bindings and giggling with the abandon of a child.

“You didn’t tell me you and Grove could ski!” Fred whooped. He practically sang the last word. “What did I tell you? Best damn skiing in America! Maybe you should come back here this winter, get some real skiing in.”

“Good effort, my boy!” a man boomed, sticking out a hand the size of a kitchen mitt. He was bigger than John, which was saying something, and thick as a tree trunk. His blue eyes danced beneath sea-anemone eyebrows and his white t-shirt twitched with tendons as he vigorously pumped John’s hand.

“This is John,” Fred said to the man. “He told me he was a falconer, but I think he’s been training with the Dartmouth boys.”

“John, Paul,” Fred said, introducing him. “Paul Petzoldt. He’s a climber—owns the Park’s guiding concession. If you ever want to learn to climb, he’s your man.”

“A falconer, eh?” Paul said. His calloused hand felt rough as granite and just as strong. “Careful—it’s a slippery slope between falconry and climbing. Have you been up the Grand yet?”

“You’re a climber?” a tall man, thin as piano wire, said excitedly, leaning out from behind Paul’s broad back. He was all sinew, with long arms, a long neck and spindly, needle-like legs that protruded from his runner’s shorts as he lurched forward to shake the hand Paul was still pumping. “Joe Hawkes. Chicago.”

“John McCown,” John said. He couldn’t stop grinning. “Philadelphia.” People were crowding around Grove, too. John winked at him. Grove was beaming.

“You’re a climber?” Joe repeated. “You did pretty well with that course. Any interest in the Grand?”

“Got lucky, I guess,” was all Joe could think to say.

More people gathered around the brothers, forming an undulating wall between them. Fred huddled with the time keeper, tallying scores.

“Well, would you look at that!” he exclaimed, rising up. “The boys from Pennsylvania did good! With a combined time of 1:18.5, the winner of this year’s race is … Grove McCown! And in second place, and on his twenty-first birthday no less: John McCown!”

A collective cheer went up from the audience. It was matched by a clap of thunder that boomed across the top of the cirque. The clouds had gone from dark to furious.

“You know, if you had just two weeks of real skiing out here with some instruction,” Fred yelled into the wind, “you’d be pretty good.” It seemed like a terrific compliment.

The sky opened up. Fred, waving wildly for help, ran for the horses. Almost everyone else began running toward the valley floor.

“See you back in the Hole, John!” Paul, who was running with his pack over his head, yelled over his shoulder. His t-shirt was already soaked.

“Let me know if you want to climb the Grand!” yelled Joe.

The wind whipped so hard it rocked John back on his heels. Rain pelted his eyes.

“What do you think about sticking around a while?” John shouted to Grove as they ran toward Fred, who was struggling to lash skis to a horse’s flanks with a lasso rope.

“It’s your birthday,” Grove shouted back, laughing.

“I think I like this place,” John yelled.

The boys were laughing uncontrollably. John shoved his brother’s dark curly head with fierce affection. Grove stumbled, then regained his balance and punched John in the side.

“SKI RACE WON BY BROTHERS AT TETON NATL. PARK,” read the headline on the front cover of the Jackson Hole’s Courier the next day. Grove even got a blue ribbon, proclaiming him the “1939 Grand Teton Nat’l Park 2nd Annual 4th of July Slalom Race Champion.”

Mt. Baker would have to wait.

And that concludes Episode 2 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening. If you liked it, make sure you subscribe to the podcast, and please share it, tell a friend about it and give it five stars on your app. Sign up for the newsletter at christianbeckwith.com so you don’t miss an update, and while you’re there check out the episode’s additional content, including bios for all the new characters we introduced today.

And if you’re really into our story of the 10th Mountain Division, please consider becoming a patron. Patrons are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack, because they support the podcast’s journalistic and educational objectives. In return, they receive access to Unabridged versions of each episode, including exclusive interviews, in-depth journalism, supporting documentation, historic images and behind-the scenes content available only to them.

Special thanks go out to our advisory board members, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergensen, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt, for their help with this podcast, as well as to Dr. Allen for his contributions. Thanks to Tom Turiano for generously sharing the interview with Paul Petzoldt, and props to Roma Deschenko and Francisco Diaz for their help in putting this episode together.

Until next time, thanks for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.