Available only to Patrons, this Unabridged version of Episode 3 explores the 10th Mountain Division’s backstory in the lead-up to America’s entry into World War II.

The episode includes interviews with Chris Juergens, PhD, the Anschutz Curator of Military History at History Colorado, on the history of Germany’s mountain troops, and Sepp Scanlin, the former director of the 10th Mountain Division and Fort Drum Museum, on the resistance the idea of an American mountain division faced from within the War Department.

Unabridged versions of both interviews are embedded in the transcript below.

This Unabridged version of the Episode also includes this complete chronology of events leading up to General George Marshall’s decision to conduct exploratory ski patrols in the winter of 1940-41. Included in the transcript below is a narrative account of the involvement of The American Alpine Club members H. Adams Carter, Bob Bates, Bill House, Walter Wood Jr. and Dr. James Grafton Rogers in the lobbying efforts for a mountain division.

See here for an overview of the characters mentioned in this episode.

Episode 3: The Drumbeats of War

—–

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and I am so glad that you’ve decided to join us for yet another episode in the story of the 10th Mountain Division. Today we’re going to be looking at the history of Germany’s mountain troops before the war, as well as Minnie Dole’s herculean efforts to establish a ski division, the resistance the unit faced from within the war department, and the way world events as well as America’s climbers helped persuade military leaders that maybe we really did need a mountain division after all.

But first, it’s time for a confession. Before I started this podcast, I spent about six months writing a seventy-page chapter for a book I was working on about the history of Teton climbing. The chapter detailed the ways Teton climbers influenced the 10th, and the ways the 10th influenced the evolution of Teton climbing after the war. Given the work I’d already done on the story, I figured I’d be able to knock out an episode every other week and chronicle the complete history of the division in about a year.

I was so wrong.

I’m currently giving myself a month to research, write, and record each episode. Unfortunately, research is taking two weeks, interviews are taking two weeks, and writing is taking two weeks —and that’s only if I stop climbing and skiing. Don’t get me wrong, I love writing about climbing and skiing, and I love working on this story. But I love climbing and skiing more, and I’m getting weak, and fat, and I’m going broke. So I’ve got to figure out a better way to do this—and for that, I’m asking for your help.

So here’s the deal. I’m going to keep producing these episodes as quickly as I can, but I’m also going to go back to my lunchtime ski breaks and to weekend adventures in my beloved mountains.

So, if you love the story of the 10th, and if you love this podcast, buy me a beer! Go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. For $5 month—which unfortunately is the cost of a beer these days in the Tetons—you’ll help me keep producing the show, and in return you’ll get extended and exclusive interviews, as well as bonus content like historic photos and full transcripts from each and every episode. And I promise to spend some of the money on food as well as beer.

I’d like to thank The Tenth Mountain Division Descendants, the Denver Public Library and the American Alpine Club for being such great partners for this show. I’m also excited to welcome a new partner, The Tenth Mountain Division Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to honoring and perpetuating the legacy of the soldiers of the Division. We couldn’t do this show without them, and we can’t do it without you, so please become a patron. Sign up for the newsletter at christianbeckwith.com. Give it a five stars on your app, tell your friends about it and help us to keep it all going.

And with that, let’s get back to the Tetons, where our hero, John McCown, is just finishing up his first season of climbing.

—-

The worst day of every climbing vacation is the day it ends. In late August 1939, John and Grove McCown and their buddy Ed McNeill said goodbye to the friends they’d made that summer in the Tetons—Fred Brown and Joe Hawkes and Margaret Smith and the Craighead twins—and, their imaginations aflame with the mountain adventures of the past two months, headed east. It was time to go back to school.

They did so as the simmer in Europe reached to boil. September 1st, 1939, Germany invades Poland.

[Radio Newscast]: “Those assembled arise and stand to greet the arrival of the German Fuhrer.”

“Poland for the first time this evening has shot at regular soldiers upon our territory. From now on bomb will be met by bomb.”

“We interrupt this broadcast of Adolf Hitler’s speech just momentarily to report a dispatch from Paris, which says that the Premier Daladier of France has now called the French Council of Ministers for an emergency meeting, which is to take place just 10 minutes from now at 5:30 a.m. eastern daylight time.“

Two days later, on September 3rd, Britain and France declared war on Germany.

But as any climber knows, once you’ve had your first taste of the mountains, all you can really think about is climbing, and, like the war in Europe, climbing in Philadelphia, where John was entering his senior year at Wharton, must have seemed a long ways away.

In 1940, Americans who wished to enhance their understanding of mountaineering lacked much in the way of suitable resources to do so. British climber Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s 1920 tome, the 600-page Mountain Craft, remained the most comprehensive book on the topic available in the country. Periodicals such as The American Alpine Journal, Sierra Club Bulletin and Appalachia had published articles on tools and techniques, but it must have been frustrating for John to peruse old issues of the AAJ, stumble upon Max Strumia’s essay on the latest climbing equipment at the back of the 1932 edition, and realize that almost none of it was available in the US.

The same could not be said for skiing. The first thirty-three pages of the 1939-1940 edition of the American Ski Annual, the country’s premier publication on the sport, were filled with ads for everything one could want for adventures on or off the piste: skis and poles and ski boots and bindings and climbing skins and ski waxes as well as a wide variety of clothing, hats and mitts were all readily available from shops around the land. Indeed, in his article The Present Status of Skiing in America in the same edition, Roger Langely, president of the National Ski Association, summed it up this way: “Skiing is big business today. It is said to be a $20,000,000 industry, a figure reached after a thorough survey of the market.”

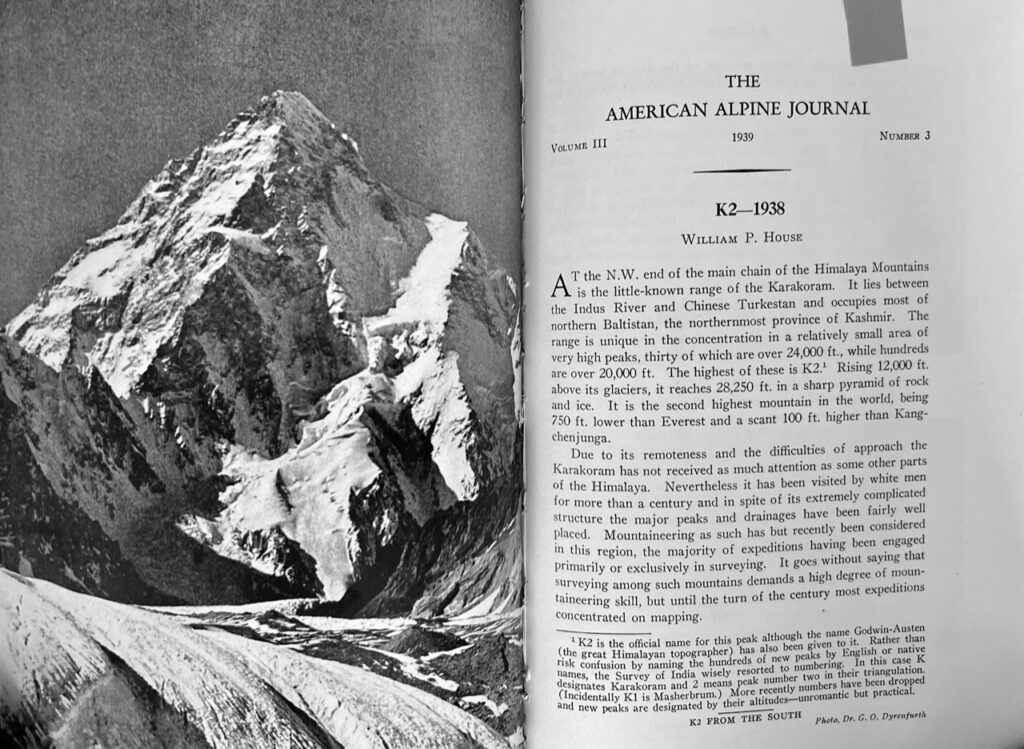

Had John perused the 1939 American Alpine Journal, on the other hand, and read the article, by Bill House, on his 1938 K2 expedition, with Bob Bates and Paul Petzoldt, whom John had just met in the Tetons, he would have noted the expedition’s list of equipment: crampons, pitons, Karabiners, rope, stoves. Almost all of it had been made in Germany, Austria, Italy or France, and purchased for the expedition through intermediaries in London.

Still, the next best thing to climbing is dreaming, talking and reading about climbing. Given the paucity of American climbers at the time, it’s difficult to imagine John finding anyone on the UPenn campus who shared his passion, so to feed his mountain dreams, he would have found no better source than the AAJ.

There, in the 1940 edition, he would have read an article by noted Yosemite pioneer Bestor Robinson on the first ascent of Shiprock, a massive volcanic plug on the Colorado Plateau that Robinson had ascended, with fellow Sierra climbers David Brower and Raffi Bedayn, using some of the most advanced ironmongery the country had ever seen. John would have marveled at the account of the second American expedition to K2, which, unlike the first, had gone horribly awry when German emigre Fritz Wiessner’s team lost four of its members high on the mountain. The geographer and explorer Walter Wood Jr was all over the pages as well, recounting his adventures in the mountains of Columbia while his wife, Foresta Wood, detailed their expedition to the St. Elias Range in the Canadian Yukon. In the back of the book, under the section entitled “Various Notes,” John would have seen an entry about his friend Joe Hawkes, who had climbed the Grand Teton in an astonishing 5 hours and 22 minutes, trailhead to trailhead, with John Holyoak. And he might have noted the absence of any mention of Margaret Smith, who had made the first manless ascent of the Grand with three other women on the very day that Joe had introduced John to climbing with their solo of the Exum Ridge.

John’s senior year at Wharton would have been bell to bell: in addition to his studies and fraternity life, he played varsity football and lacrosse, ran track, and was part of the Mask and Wig’s theatrical production of a musical comedy. It’s unclear when or where he would have trained for the mountains: climbing gyms were fifty years in the future, and there simply weren’t many cliffs of any size near Philadelphia, where he was going to school. But whatever he did to feed his stoke in the climbing-poor environs of Pennsylvania worked, for the moment he graduated in the spring, it was back in the Ford with Grove, Ed and another friend, Pouty Edwards, for a second annual western road trip. And when they got back to the Tetons they didn’t just ease into it; they plunged headlong.

The Teton range is remarkably compact, with the majority of its significant peaks—the Grand, the Middle, and the South Tetons, as well as Teewinot, Mt. Owen and Nez Perce—assembled in a knotted clutch at its heart known as the Cathedral group. To the north rise other pointy and compelling objectives, but they’re more remote, harder to access and thus less seldom climbed, even today.

One of the more obscure, and impressive, mountains in the northern part of the range is called Bivouac Peak. Its south face features a convoluted swathe of stone nearly 2,000 feet high—a remarkable feature, particularly in a country that had barely begun to dabble in big-wall climbing.

Ordinarily, after eleven months off, one reaquaints one’s body and mind with the movements and psychological gyrations necessary for harder climbs by doing easier ones. This was apparently not John’s style, for in early August, after a single warm-up climb on the south face of Symmetry Spire, John led his team to Bivouac’s base.

Perhaps he’d had found Robinson’s account of the first ascent of Shiprock inspiring, for, as Leigh Ortenberger and Renny Jackson note in their guidebook, A Climber’s Guide to the Teton Range, ”In early August 1940, three-quarters of [Bivouac’s south] face was climbed by a group of Philadelphia lawyers, John McCown II, C. Grove McCown, Edward McNeill, and Thomson Edwards; their remarkable attempt was stopped by lack of time and an understandable reluctance to spend the night on the face. The same party later continued up Moran Canyon to make the first ascent of Cleaver Peak.”

While Ortenberger and Jackson might have erred on the students’ avocation, they nailed the assessment of their attempt.

Bivouac’s south face would remain unclimbed until 1947, when Dick Pownall, one of the great Teton pioneers of the post-war years, made its first ascent with Paul Kenworthy. The next time a new route went up on the face was September 2, 1969, when George Lowe, one of America’s greatest alpinists, established a fifteen-pitch route on the face with Juris Krisjansons. Krisjansons returned the following year to establish another line on the face, a Grade IV 5.9 that he climbed with legendary Yosemite big-waller Yvon Chouinard.

To say that it was bold of John to jump on the south face of Bivouac as one of the first climbs of his second season of climbing is an understatement. The fact that he and his friends almost made it: well, that’s what the Brits would call gobsmacking.

And they didn’t stop there. On August 14, John, together with Ed, Pouty Edwards, Thomas Johnston of the Sierra Club and Charles Webb of the Dartmouth Mountaineeing Club, launched up the north face of Nez Perce, a nearly 12,000-foot-high peak in the Cathedral Group that looms over Garnet Canyon. North faces are cold and forbidding in general, and the north face of Nez Perce adds size—it’s some 1,500 feet high—as well as dubious rock quality and two steep snow couloirs on either side that lend it an alpine ambiance. The first ascent of the face had been made five days earlier by Jack Durrance and fellow Dartmouth Mountaineering Club founding member Hank Coulter.

You’ll remember from our last episode that at this juncture in the evolution of American climbing, Durrance ranked among the hottest young climbers of his generation. He’d arrived in the Tetons at the behest of Paul Petzoldt in 1936 and proceeded to execute a number of routes so bold that Fritz Weissner had invited him on his ill-fated 1939 expedition to K2.

As Chris Jones, whom we met in our last episode, put it, ”Climbing in North America at that point, while coming along nicely, remained a far cry from the levels of technical difficulty at play in Europe…. [Yet] Durrance and his Munich friends were of a new generation of climbers…. Durrance was the first climber in the Tetons to seek out bare ridges and smooth walls, routes which often lacked ledges and natural belays.”

Indeed, on the day John and company started their ascent of the north face of Nez Perce, Durrance and Coulter were on the west face of the Grand, establishing one of the country’s most difficult routes.

The pair were friends with Charlie Webb, and it’s likely he had a general sense of their line on Nez Perce. “Made (direct?) ascent of Northwest Face by a new route starting at the hourglass,” they noted in the summit register—though, as Ed McNeill would later write to Leigh Ortenberger, “If there was any originality to [our] climb it probably came about by our realization that we had lost the Durrance route early [on] and we had to make our own.”

Still, their effort begs the question: where did the boys get the gumption to embark on a route that two of the country’s best climbers had just opened up?

And what possessed John to think that he could undertake such ambitious outings with a single season of climbing under his belt?

Angels look after fools and climbers, and perhaps John had a particularly attentive one watching over him that summer. Be that as it may, his 1940 climbs—which, in December of the same year, would result in his election to The American Alpine Club—were no anomaly. The following summer, as we’ll learn in our next episode, he would push the boat out an order of magnitude further.

“Until one is committed,” Johann Wolfgang von Goethe is said to have said, “there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back…. the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too…. Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it.”

Four and a half years later, in the dead of winter, on the flanks of Italy’s Riva Ridge, John would lead his soldiers up the mountain’s hardest line under cover of darkness to capture the German soldiers on top without a casualty. The boldness of that audacious action, which would help break Hitler’s Gothic Line and end the war in Europe, was on full display that summer of 1940 with John’s climbs.

And America would need his boldness, for even as John and his future 10th Mountain Division comrades were learning the ropes, Germany’s alpinists had already spent generations mastering the art of climbing and fighting in the mountains.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: To really understand the impetus behind Mountain Warfare in the 19th and 20th centuries. You have to go back to the 18th and even the 17th century when you had, you know, line infantry formations and lots of soldiers lined up with muskets shooting at each other over open fields.

I’m speaking with Ninety Pound Rucksack advisory board member Dr. Chris Juergens, the Anschutz Curator of Military History at History Colorado and the 10th Mountain Division Resource Center.

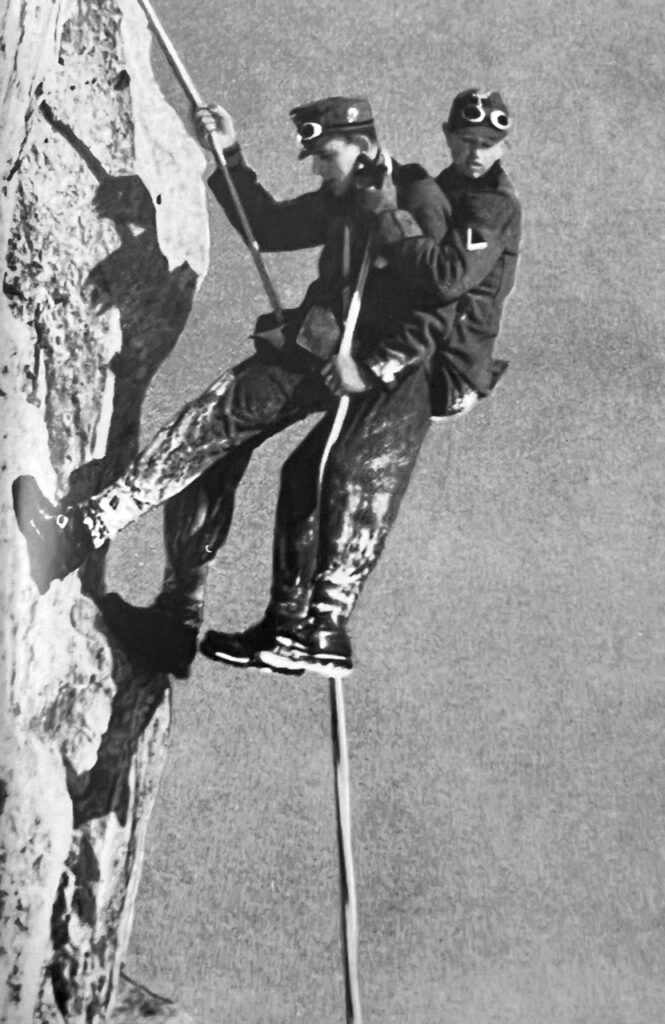

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: The armies recognized that there was a need for more independently minded troops, especially for adverse terrain. So moving through forests, moving across hills where communication as a problem, you needed more specially trained elite troops that could handle that kind of environment.

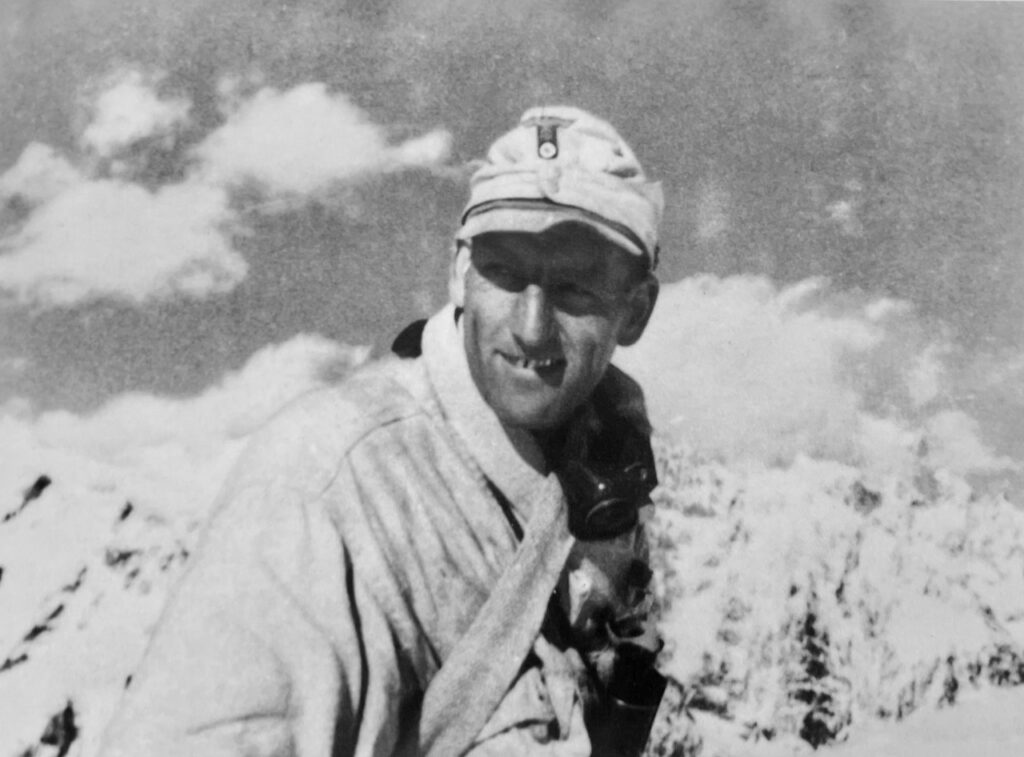

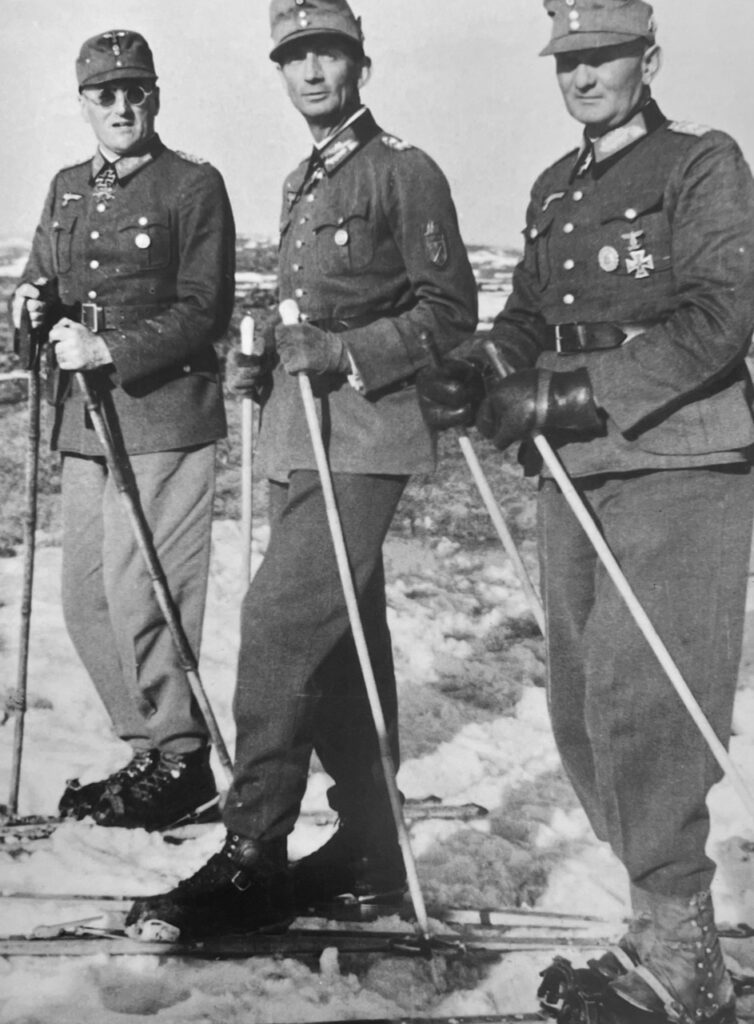

The realization would prove critical to the formation of the most famous mountain troops in the world, the Gebirgsjäger, or mountain hunters.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: So that actually started in central Europe, in Germany, and they became known as Jaeger, which is the German word for hunters. These were just light infantry outfits and you see that terminology carried forward. So when the first mountain troops are being formalized in the 19th century and early 20th century, that term Jaeger comes to encapsulate not only the light infantry divisions, but also the mountain troops that are forming at this time as technology progressed, war was moving to new environments. I mean, they had, they had new possibilities of combating each other. And it was actually during the Napoleonic wars that you see for the first time warfare happening in the mountains and generals kind of debating how best to accomplish that. For example, Switzerland was essentially impassable terrain for armies for much of its history. And all of a sudden you had French troop climbing mountain passes and fighting the Swiss resistors. And so for the first time, you have armies really contemplating, you know, what it means to fight in the mountains.

Thanks to the natural topography of Europe, the fundamentals of mountain warfare quickly became evident.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: Elevation always gives you a certain degree of advantage. I mean, not only do you have a better feel of the view, but your enemy also has to exhaust himself as he is charging up, you know, a hill or a mountain side. But on top of that, when you get to more, more alpine conditions, controlling mountain passes is always much easier for the defenders. They can really dig themselves in there and they can lock down those passes with far fewer numbers than the attackers are able to bring to overwhelm that position. I mean, even in flatland conditions, the attacker, in order to have a successful attack, you always want to have, you know, two or three times the enemy that you’re, that you’re facing. But when you’re closed down into those narrow mountain passes you don’t really have a chance to overwhelm the defenders with numbers. And so the defenders can, can hold those passes with far fewer numbers than the attackers can bring against them. And so that’s a huge advantage.

Much has been made of the fact that the lobbying for and composition of the 10th Mountain Division came from civilian organizations like the National Ski Patrol System and American Alpine Club, an influence unprecedented in American military history. In Germany, however, where mountain culture colored the very fabric of national identity, it was simply an organic extension of society.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: The first instances of troops learning how to ski and mountain climb actually come from civilian instructors. So the German army, the way it was recruited, the German Imperial army. So we’re talking late 19th century. The way they were recruited was that the country was basically divided into these cantons as they called them, and different cantons were responsible for furnishing the troops for their respective regiments. And so you got really local flavors in those regiments because they would be recruited from the nearby towns basically. And so naturally you had you know, a lot of those southern units that were being raised in southern Britain back and southern Bavaria. There was already a sort of a local affinity for the mountains. And so it was in the late 19th century that some of those local mountain communities decided to do things like promote ski races or climbing contests with the locally stationed troops. And so the first mountain warfare training that you really have or, you know, the early kind of versions of that that you have in Germany are actually being conducted by the civilian communities with their respective kind of local troops.

While armies had been fighting limited battles in the mountains of Europe for more than a century, it took war in the Dolomites, Julian and Tyrolean Alps for them to learn the lessons of mountain warfare the hard way.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: The first formalized troops are coming together late 19th century, but the really the first time that they’re getting battle test is during the first World War. The first place where this really happens with gusto is on the Italian front. So this is where the Italians and the Austria-Hungarian are fighting each other and it’s right in the Eastern Alps, and it doesn’t take long for them to dig into those positions and to be fighting really intense mountain warfare there for a number of years.

In May 1915, hoping to reclaim some of its historic territories, Italy abandoned all pretense of neutrality and launched an offensive against its former ally Austro-Hungary in the mountainous regions that made up their border. Italy had vastly superior numbers and equipment on its side, but the Austro-Hungarians enjoyed a distinct advantage: they held the high ground.

Fighting at altitudes of up to 12,000 feet and in temperatures as low as twenty below zero, the two sides slugged it out for two and a half years in what came to be known as the Battles of Isonzo. The results were horrific. Hundreds of thousands of the region’s inhabitants were displaced or killed. The Austro-Hungarians lost some 200,000 soldiers in the battles; the Italians lost 300,000 men, half the total of its casualties from the entire war.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: They fired so much artillery at each other that they actually changed the face of those mountains, which is really remarkable. If you look at aerial photographs from the First World War, over the years of that combat, you can actually see the mountains change.

Their armies were battling climate and topography as well as one another. “60,000 troops died from avalanches alone,” wrote John de la Montagne, a 10th Mountain Division soldier who would go on to play a pioneering role in Teton mountain rescue and avalanche science after the war. “The casualties were caused both by natural avalanche releases,” he wrote, “and by artificial releases set off by foot soldiers in tactical operations…. One report indicated that 3,000 Austrians were killed in one 48-hour period by the Italians, who blew up a summit-ridge snow cornice, precipitating a great avalanche wave that descended onto the Austrian positions.” On December 16, 1916, a day known as White Friday, blizzards caused a series of massive avalanches that killed as many as 10,000 troops on both sides. As the ski pioneer and Austrian General, Mathias Zdarski, put it, “the mountains in winter were more dangerous than the Italians.”

Finally, in October 1917, Germany sent two mountain divisions to the aid of its Austrian counterparts.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: And the first sort of high profile incident that that happens there kind of showcases the mountain warfare innovation is the famous 12th Battle of the Isonzo or the Battle of the Caporetto. And that’s when the German Alpine Corps joins the Austrians and brings in some new tactics and some new innovations to help them break through the Italian defenses. And actually was a young officer, Irwin Rommel, who became famous during World War II as the Desert Fox. He was one of the officers of that Alpine Corps, and he actually gets awarded the, the highest Imperial German award for valor, sort of their equivalent of the Medal of Honor he gets for that battle. And what the Germans bring to the table for the first time is in that theater are these infiltration tactics as they call them. So they actually bypass strong points in the Italian defenses and attack the Italian rear. So the emphasis is really on speedy movement past the defenses rather than neutralizing every last one. So it was a really, a monumental event for that front.

Rommel’s victory was decisive. Some 40,000 Italians were killed or wounded, while another 280,000 were taken prisoner.

Rommel won the battle, but Germany and Austro-Hungary lost the war. In its aftermath, the victors drew up the Treaty of Versailles, and in the process set the stage for World War II.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: After the first World War, the German army was cut down to the so-called a hundred thousand man army. So they were, they were cut down to next to nothing, and this affected all branches of service. And so even the mountain troops that had been developed during the First World War were cut back until they were just one battalion in the entire army. So in 1935, when they reactivated the German army in earnest and Hitler sort of disregarded the restrictions of the Treaty of Versailles that had cut it down to a hundred thousand men, they started expanding rapidly. And one of the areas of expansion was in mountain warfare for mountain troops.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: So they expanded that initial battalion and they created the first mountain troop division, the first Gebirgsjäger division and then they expanded it with two more divisions as a result of the Austrian Anschluss. So when the Austrians were brought into the German Empire, into the Third Reich, they assimilated the Austrian army, and the Austrians had been able to maintain a larger mountain force than the Germans had. And so the new Wehrmacht, you know, the second and third mountain divisions were actually comprised of Austrians initially.

Part of that is too, is that you have kind of this increase in, in military adjacent civilian clubs so that you have, you know the German Alpine Club, you have the the Glider Club, you know, that sort of thing. And part of the impetus behind those clubs in Germany in the thirties is because of those… in the twenties and thirties… is because of those restrictions from the Treaty of Versailles.

The German army was actually forbidden from utilizing certain technologies. They were, you know, obviously restricted to that a hundred thousand man army. And so those clubs, those civilian clubs actually offered loopholes for some of these training gaps. And so you had, you know, the automobile club that also happened to be working on, you know, technologies that would be similar to what the army would be employing later. You had the glider clubs so that you could train pilots when you weren’t allowed to have an air force and you had these climbing clubs where you can kind of expand your mountain warfare training capacity beyond what that single battalion that you were legally allowed to have would allow you to do. And so the civilian clubs were really important there.

By 1940, as we’ll soon see, the efforts of Minnie Dole and the American Alpine Club had begun to pay off, and the US Army had begun assembling experimental ski patrols to test the alpine waters. But like the gap between US and European climbing standards before the war, the gulf between American aspirations and German realities was vast.

[Dr. Chris Juergens]: So even while the US was contemplating adding mountain troops to its repertoire, and the goal there was to form an entire division of Alpine troops, right? And what ultimately results in the 10th Mountain Division. At the same time, the Germans started the war in 1939 with three mountain divisions, and by the end of the war the count varies a little bit depending on, on how you choose to count these divisions, but they effectively have 12 mountain divisions, 12 Jaeger divisions that have some rudimentary mountain training and one ski Jaeger division as well. So that the numbers are astronomical on the German side in terms of emphasizing that mountain warfare in a way that was never realized in the US Army.

—-

Ask any Teton climber walking the wooden boardwalks of Jackson today who made the first ascent of the Grand and they’ll likely respond, “Billy Owen.” Which is true, to an extent. Yet had it not been for the climbing virtuosity of Reverend Franklin Spalding, who discovered the key section of the route and then soloed its crux before downclimbing to lend his partners a rope, the Grand might not have received its first ascent until well into the 20th century.

Ask anyone with a passing familiarity with World War II to characterize the 10th Mountain Division and they’re likely to tell you they were Minnie Dole’s ski troops. Which is true, to an extent; yet in an event as complex and broad and transformative as the war, it’s a fragment of the real story—a story that influenced the United States military, the outcome of the war in Europe and the development of outdoor recreation as we know it today.

The version of the Division’s story that’s easiest to tell is that Minnie Dole was the locomotive, caboose and train tracks of its development. And because Dole himself told the story in real time, and because national media amplified the story as it was unfolding, and because subsequent retellings of the story took this version of events as the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, it has become “fact.”

The real truth, though, is more complicated, which is why it’s less often told.

Let’s start with the true truth about Dole’s efforts. You’ll remember his February 1940 apres-ski discussion in Vermont with prominent American skiers Roger Langley, Robert Livermore, and Alec Bright, at which they discussed the Soviet Union’s late 1939 invasion of Finland and the Finnish guerillas’ successful frustration of Stalin’s birthday party celebration in Helsinki. Inspired by the Finnish resistance, Dole and his mates discussed America’s need for its own ski troops—and who better to fill that need than the National Ski Association, of which Langley was the president, and the fledgling National Ski Patrol System, of which Dole was the director.

Dole’s lobbying efforts began in earnest in the late spring of 1940, amidst the growing din of Hitler’s advances in Europe.

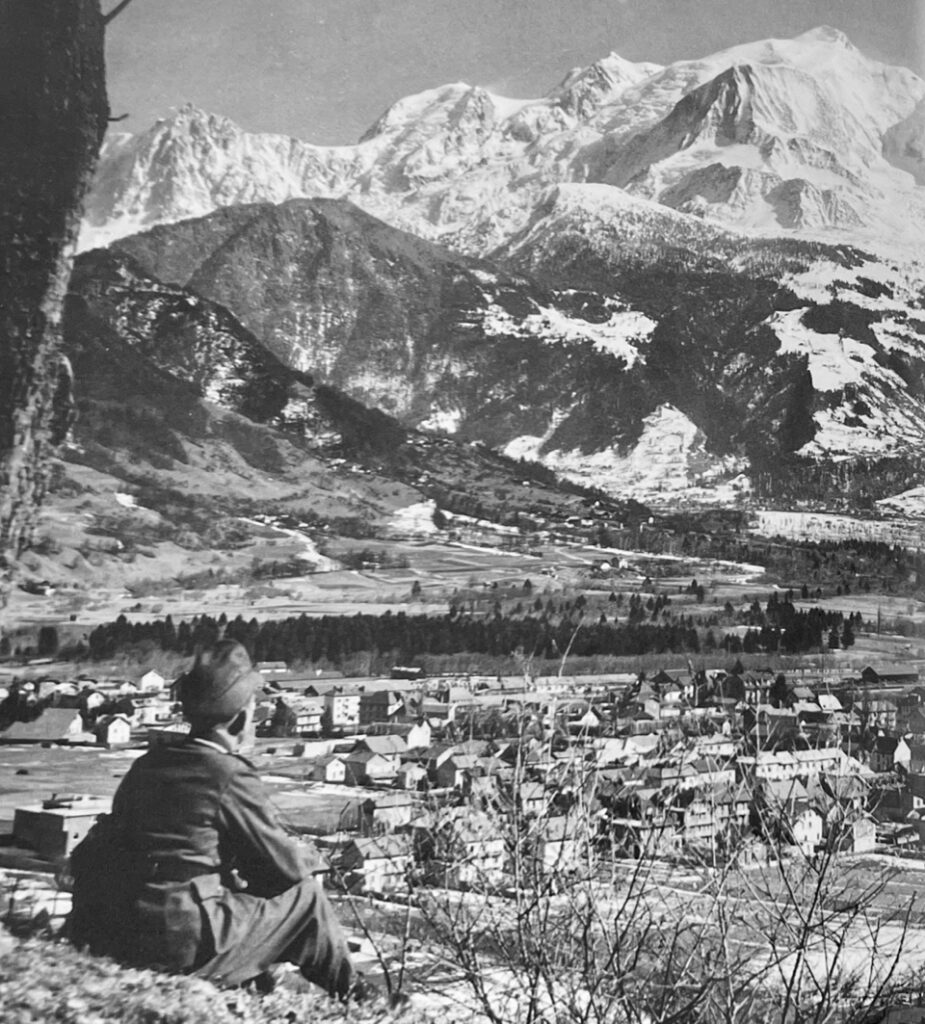

April 8. Germany launches a surprise attack on Norway. 100 miles above the arctic circle, one German mountain regiment–made up primarily of Austrians—sails into the port town of Narvik under cover of storm aboard ten destroyers in order to secure militarily critical iron ore from Sweden before the British can do so.

[Radio Newscast]: It was about dawn this morning that the first reports came in saying that German troops were crossing the frontier into Denmark. At the same time, attacks were being delivered from the sea on a number of Norway’s biggest ports.

May 13th.

[Radio Newscast]: This is London. History has been made too fast over here today. First in the early hours this morning came the news of the British unopposed landing in Iceland. Then the news of Hitler’s triple invasion came rolling into London climaxed by the German air bombing of five nations. Then at nine o’clock tonight, a tired old man spoke to the nation from number 10 Downing Street. Neville Chamberlain announced his resignation. Winston Churchill, who has held more political offices than any living man, is now Prime Minister. Winston Churchill has never been known for his caution, and when he has completed the formation of his new government, you may expect this country to begin to live dangerously.

May 13. Winston Churchill addresses parliament for the first time.

[Winston Churchill]: We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I will say it is to wage war by sea, land and air with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us. To wage war against the monstrous tyranny never surpassed in the dark and lamentable catalog of human crime—that is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word, victory. Victory at all costs. Victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be, for without victory, there is no survival. Let that be realized. No survival for the British empire. No survival for all of the British empire stood for. No survival for the urge and impulse of the ages that mankind will move forward towards its goal.

May 14.

[Radio Newscast]: Hitler added another to his bag of small nations today, the fifth in 14 months when the Dutch army laid down its arms everywhere except in the extreme southwestern part of the country. And even there, the Germans have almost reached the sea.

In Narvik, the Germans lose their ships and their position to a British naval counterattack. Two thousand surviving mountain troops and 2,600 sailors retreat to the snow-covered mountains surrounding the town, which rose to 4,600 feet, more than half of which was above tree line. With no winter clothing, no camouflage, no tents, sleeping bags, skis or snowshoes, the German mountain troops manage to hold off twenty-five thousand Allied troops for two months, until Germany’s successes in France force the Allied forces to withdraw.

[Chris Juergens]: They’re hailed as great heroes. They write books, they make movies about this immediately. That’s a big propaganda hit for the Germans. It’s really a way that kind of romanticizes the mountain troops as far as the German public is concerned. And of course at the same time that you have this great inspirational example for the Americans and for Western forces in general in the Finns that are successfully resisting that Soviet invasion. You also have this at the same time hitting the headlines, this implicit threat of these German mountain troops who apparently are able to hold off many times their numbers coming from the on the Allied side.

June 10. Italian Prime Minister Benito Mussolini declares war on England and France as Italy and Germany join forces.

[Radio Newscast of Mussolini’s speech in Italian]

June 14th.

[Radio Newscast]: The French resistance has collapsed and the Maginot Line has been broken, destroying all French resistance. Paris is an open city.

Sometime in June, Secretary of War Woodring writes back to Roger Langely, politely declining his offer of the National Ski Association’s resources in the war effort.

June 18. Winston Churchill addresses the House of Commons.

[Winston Churchill]: The Battle of Britain is about to begin upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us. Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him. all Europe may be freed and the life of the world may move forward into broad sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, will sink into the abyss of a new dark age, made more sinister and perhaps more protracted by the lights of perverted science.

June 20. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt replaces Woodring with the interventionist Henry Stimson as the Secretary of War.

Which is just about the time that Minnie Dole kicked his lobbying efforts into high gear.

On June 10, he wrote a memo to the more than 3,000 members of the National Ski Patrol, gauging their interest in volunteering for the war effort. The responses were overwhelmingly positive.

July 8: Dole makes his argument for a ski division and offers the services of the ski patrol to Gen. Irving Phillipson. “You do not have to try and sell me, for you are right,” Dole would later recall Phillipson saying. “I should send you to Washington with my blessing, but they would only say ‘There’s Phillipson shooting off his face again.’ You better go, but it will be a long uphill battle.””

July 10, 1940: Germany launches an air war, known as the Battle of Britain, against the United Kingdom.

[Radio Newscast]: This is Trafalgar Square. The noise that you hear at the moment is the sound of the air raid siren. I’m standing here just on the steps of St. Martin’s in the field. A search light just burst into action off in the distance, one single beam sweeping the sky above me. Now people are walking along quite quietly. We’re just at the entrance of an air raid shelter here and I must move this cable over just a bit so people can walk in. There’s another search light just square behind Nelson’s statue. Here comes one of those big red buses around the corner, double deckers. They are just a few lights on the top deck in this blackness. It looks very much like a ship that’s passing in the knife and you just see the portholes.

July 18: Dole writes President Roosevelt, offering to recruit experienced skiers to help train troops in ski patrol work. Citing the effectiveness of ski troops in Finland’s defense against the Soviet invasion, Dole points out that “in this country there are 2,000,000 skiers, equipped, intelligent, and able. I contend that it is more reasonable to make soldiers out of skiers than skiers out of soldiers.” FDR’s refers the matter to the War Department for Study.

September 6: President Roosevelt addresses the nation.

[President Roosevelt]: Men and women of the United States. On this day, more than 16 million young Americans are reviving the 300 year old American custom. They are obeying that first duty of free citizenship by which from the earliest colonial times, every able bodied citizen were subject to the call for service in the national defense. The United States, a nation of 130 million people, has today only about 500,000 men who are officers and men in the army and the National Guard, but in other nations, smaller in population, have four and five and 6 million men trained in their armies.

September 12: Dole secures a meeting with Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall at which he presents his views and gives him a three-page “Winter Training” proposal to support the argument for mountain troops. At the meeting’s conclusion, General Marshall rises, shakes hands and says simply, “Gentlemen, you will hear from me shortly one way or the other.””

Mid-September, 1940: Marshall sends the “Winter Training” proposal along with supportive memorandum to Colonel Nelson M. Walker, assistant chief of staff in charge of army operations and training.

September 22: Germany, Italy and Japan sign the Tripartite Pact, creating a defense alliance between the countries that’s intended to deter the US from entering the war.

September 24, 1940: General George Marshall writes Dole, “I am informed by the G-3 Division that two general plans are under study and in preparation: (1) the establishment of an agency for test and development of clothing and materiel for winter warfare operations, and (2) the procurement of skis and other equipment with which to begin ski instruction in certain divisions, initially for morale and recreational purposes.”

October 6: Dole meets with Colonel Nelson M. Walker and Colonel Charles Hurdis of the General Staff, who invite the National Ski Patrol System to consult on equipment, format and structure for the series of experimental ski training sessions Marshall has just approved. The National Ski Patrol System is given enough money to open an office in Lower Manhattan from which to assist, and by late November, as we’ll soon see, soldiers have begun conducting cold-weather manoevers on skis on Mt. Rainier, as well as in Lake Placid and Old Forge, New York, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Wyoming. The earliest chapter of the 10th Mountain Division is about to begin.

And that’s the story that’s easiest to tell, because it has already passed into legend. The real story, though, is more complicated.

Much more complicated.

Here’s the thing about the US military before America’s entry into World War I. The country was awash with well-meaning patriots like Dole who had their own ideas about how to prepare for war, but the Army was the largest, most regimented bureaucratic system the country had ever known, and as patriotic as many of the civilian ideas might have been, they were either unrealistic, foolish, naive, dangerously out of lockstep with the military’s priorities and modus operandi or a combination thereof.

[Sepp Scanlin]: The active service at that point consisted of eight divisions in 1939 to 24 divisions by 1940. But what that really means is 270,000 troops.

I’m speaking with Ninety Pound Rucksack advisory board member Sepp Scanlin, a 10th Mountain Division veteran and military historian who until recently served as the Director of the 10th Mountain Division Museum in Fort Drum, New York.

[Sepp Scanlin]: In comparison to our 24 divisions, the Germans had already fielded 189 divisions by 1940. So we are still woefully behind the mass mobilization that would eventually be required. A lot of this is being hashed out in 1940, 1941, and it really doesn’t come to a true plan until mid 1941 when the Army sits down and actually develops what they call the Victory Plan. And this is a total assessment on what they think the nation can field for military force in the coming war.

This plan, which was known as the Victory Program, estimated that to defeat Nazi Germany would require the United States to raise a force of 215 divisions comprising 8.7 million men by the summer of 1943 —and that didn’t include the Navy. Such an effort would also reuire the complete retooling of society to serve as the “Arsenal of Democracy,” that is, the industrial base necessary to produce the complete spectrum of food, clothing and materiel needed for war.

To go from 270,000 to 8.7 million soldiers in three years was the largest initiative the country had ever undertaken, and Hitler’s ongoing successes in the spring and summer of 1940 made it clear that doing so was imperative. But within the War Department, precisely how to do so was a matter of great debate.

For context, in 1940, an infantry division—the smallest Army organization deemed capable of conducting independent combat operations—had an authorized strength of 15,245 soldiers.

[Sepp Scanlin]: And in the Army’s formal study of this after the war I thought there was a great quote. It said in 1941, the calculations for the military and strength in sum dealt with an unknown future as well as a doubtful present. Because we really didn’t know where we were gonna be fighting, what would be needed and what materiel we would need to support that force.

Remember when General Phillipson told Minnie Dole to go to Washington, but it will be a long uphill battle? He was referring to the obstructionism he knew Dole would encounter from within the military—and that would follow the 10th Mountain Division like a shadow right up to its late 1944 deployment to Italy.

[Sepp Scanlin]: I think a lot of the obstruction comes from different views on how to balance limited resources versus known risks. You know, is the juice worth the squeeze, as the saying goes: Can we get to a functional organization in the time that we believe will need it? The ones that are the obstructionists are really those charged with building a massive army very quickly and the envisioned timeline for training and division at, at this stage in the war as they expected to go from recruitment to fielding in one year.

For context, in 1940, an infantry division—the smallest Army organization deemed capable of conducting independent combat operations—had an authorized strength of 15,245 soldiers.

[Sepp Scanlin]: They saw it as a, “Hey, this is in a too-hard-to-do” block. If you want me to give you 215 divisions by 1943, we can’t build one of these, one of those, one of these. You’re gonna get 213 that look a lot alike. And then we’ll just tweak them based on the circumstances.

To tell a good story, it’s nice to have a hero and a villain. The 10th Mountain Division had that: they were the good guys, and Hitler and the Nazis were the bad guys. If we just wanted this story to unfold nicely along the surface of the most complicated event the species had ever encountered, we’d run with that.

If we wanted to go one step below the surface, Minnie Dole, verbose, tenacious and tireless, would be our hero, and we’d find a single person within the military who embodied the sort of obstructionism Dole had begun to encounter during his 1940 summer campaign. And indeed there is that person, and his name is Leslie McNair.

But, like just about everything else in our story, the reality is more complicated.

[Sepp Scanlin]: Leslie McNair, I mean he’s pretty senior at this point, so he is already a general officer. He’s personal friends with George Marshall. In fact, George Marshall brings him in to basically build out the army. The task is given to General Marshall to do both. He’s both the chief of staff of the Army and he’s going to be the commander of the general headquarters. He knows he can’t commit to both. So he brings in General McNair, he’s essentially executing all the duties with very limited requirements to go in and get stuff approved by General Marshall. So he is now building this army that Marshall needs to fill these war plans.

In reality, they are developing the first US global army that could be called to operate anywhere on the globe. This is nothing the Army had done before. We hadn’t built an army of this scale to operate worldwide until this point

To General McNair, the solution was obvious.

[Sepp Scanlin]: He sees that Henry Ford has built all the same things, right? We’re gonna have common camps, we’re gonna have common training programs, and we’re gonna have common divisions that come out at the end. So a very industrialized process because that’s the way you can get the most stuff done in the shortest amount of time.

Both he and Marshall are being bombarded at this stage with all sorts of recommendations, ideas from, you name it, from congressman to everyone like Minnie Dole, who’s got an idea that’s knocking on his door and trying to offer these by necessity. He’s trying to limit this.

There was another reason for resistance to a specialized division from within the military. The United States Army in 1940 was decidedly a flatland, warm-weather operation, with almost no cold-weather or mountain protocols, training regimens or equipment. Everything related to cold-weather and mountain fighting would necessarily need to be started from scratch.

[Sepp Scanlin]: There’s really no doctrine for how to fight in mountainous or cold weather. We were really coming at it from, that’s what I mean from the tactics and techniques perspective, the equipment perspective, and then the organizational perspective. So none of it’s on the shelf.

German, Austro-Hungarian, Italian, and French forces had fought in the Italian Front, also known as the Alpine Front, during World War I. As a result, those armies understood the need for mountain units. Lacking similar first-hand experience, the US didn’t.

[Sepp Scanlin]: As many troops were as engaged on the Alpine front as there were on the western front. And that’s where most of our adversaries really begin to understand the need for specialized mountain troops.

One of those officers who experiences that firsthand as a company commander Erwin Rommel. It’s because of his innovative use of the terrain seizing critical high ground in a mountainous environment that limits the Italian’s ability to maneuver. It literally almost knocks the Italians out of the first World War.

In the inner-war period, he actually publishes Infantry Attacks. And that book really details and kind of expands upon his experience as a mountain troop commander in the Alpine front.

There’s some study of this in the United States. Some of the critical leaders like George Patton are studying it, but all the people that we’re gonna talk about this, senior leaders experience, their combat is on the western front, the trench warfare, not in the mountains. And you can read about it, but it’s not the same as kind of that firsthand experience that you’re always going to pull from kind of in your development process from a military perspective.

If you’re General McNair, here’s another factor for you to consider: Transportation. The most effective lightweight piece in the Army’s arsenal was the 75 mm pack howitzer, which could shoot an eighteen-pound shell 5.5 miles. It weighed 1,440 pounds fully assembled and could be broken down into six loads of 225 pounds each in order to be moved across difficult terrain.

How do you move a 75 mm pack howitzer through snow and mountainous terrain, even when dissasembled? Pack animals: mules and horses. And how would you deploy a unit overseas when you needed to ship its mules with it? This seemingly simple consideration would dog the 10th Mountain Division all the way through to its eventual deployment.

But while General McNair was trying to figure out how to build an eight-million-man army, essentially from scratch, another factor was coming into play as well: the real world consideration of the battles being fought in Europe.

On October 28, 1940, Italian forces invaded Greece through its mountainous northern border with Albania, only to be driven back into the mountains as winter settled in. Ill-equipped for either cold-weather or mountain warfare, the Italians suffered catastropic losses, including nearly 14,000 dead, 50,000 wounded and more than 12,000 cases of frostbite, before Hitler stepped in to bail out his hapless ally. Coupled with the lessons learned from the World War I experiences in the Italian Front and the German mountain troops’ successes in Narvik, the so-called Greco-Italian war persuaded planners in the War Department to reconsider the merits of a mountain unit—and to reach out to America’s climbers for help.

But before we go there, I’d like to offer a clarification. In Episode 1, I used Dr. John Imbrie’s May 1940 entry in his chronology of the Division to support my assertion that credit for the Division’s inception belonged equally to the Army, Minnie Dole and The American Alpine Club.

Since then, with the help of our advisory board and Dr. Lance Blyth, Command Historian at NORAD, I’ve combed through the records, and the earliest official AAC involvement we’ve been able to find took place not in the spring of 1940, as Imbrie stated, but in the fall.

We now believe Imbrie conflated the American Alpine Club’s lobbying efforts with Roger Langely’s May 1940 letter to the War Department. This in turn leads us to believe that credit for the unit’s initial momentum belongs to Minnie Dole and the national ski patrol system.

But remember how John McCown was frustrated by the almost complete lack of homegrown climbing instruction and equipment available to Americans before the war? As the Greeks continued to hand the Italians their derriers on frozen platters in the Albanian mountains, the US Army was growing not only frustrated but concerned—and in a time of great national need, Minnie Dole was hardly the only lover of mountains to step forward.

Which is where H. Adams Carter and Bob Bates, the young American Alpine Club members we met in our first episode, come back into our story.

The upper echelons of the skiing, climbing and mountaineering worlds before the war were populated by a relatively small number of people who enjoyed a considerable amount of overlap. By way of example, I refer you to the 1938-39 edition of the American Ski Annual. In it was an article by Roger Langely on the 1938 national ski championships, in which Dartmouch ski coach Walter Prager took third place, just behind Dartmouth ace and defending champion Dick Durrance, Jack’s brother. Minnie Dole was back in the pages, detailing the first tentative steps of the brand-new National Ski Patrol System. Carter, former president of the Harvard ski team, recounted the adventures of the US Ski Team, of which he was a member, in the 1938 Panamerican ski championships in Chile, while Bestor Robinson detailed his reconnaissance of the three hundred mile Sierra Crest Ski Trail, on which he was able to work out the merits of lightweight backcountry ski gear. By the end of 1940, all of these men would be engaged in the matter of mountain warfare on behalf of the Army.

The overlap, though, went further in one direction than the other. As Minnie Dole had pointed out to President Roosevelt, there were 2,000,000 skiers in America before the war. What he declined to mention was that the vast majority of them were “lodge skiers,” adept at a turn and even better at talking about it, libation in hand, before the comforts of a warm fire.

As we pointed out in the last episode, there were fewer than 500 technical climbers in America before the war. Like Carter and Robinson, most of them skied, but their skiing was a means to a greater end, one Sir Arnold Lunn had in mind in the 1920s when he devised his downhill and slalom races. To alpinists, skiing was how you got up and down a mountain.

To climb a big route, one can expect to move for eight or ten or twelve hours at a time over objectively hazardous terrain, where the consequences of a mistake can be grave. Doing so requires a broad range of skills, as well as physical fitness and the psychological ability to compartmentalize. To make difficult moves in what’s known as “you-fall, you-die” terrain, it’s helpful to put your fears in a box so you can focus. Climbers make scary moves all the time while frightened out of their gourds—hence the term “sketch”—but trust me when I say it’s preferable to make them when your mind is under control.

Physical and psychological competence in all terrain and all climactic conditions are hallmarks of a competent mountaineer. They rely, in turn, on equipment and clothing climbers today refer to as “bombproof.” When you can’t fail, your gear can’t either.

As the Army began to realize that the German successes in the Italian Front and Narvik and the Italian disasters in the Albanian mountains stemmed from mountaineering competence, reliable gear or a lack thereof, its conception of what a mountain unit could and should look like started to shift—and the American Alpine Club’s offer to help in the fall of 1940 began to look more appealing.

[Sepp Scanlin]: Minnie Dole’s initial belief in support for troops is the Finnish winter war, which is not a mountain battle, it’s a ski winter warfare battle, right? Like they’re not summitting peaks, they’re surviving in extreme cold conditions, but they’re essentially cross-country skiing. So the mountain part of it isn’t as profound, but by the time you get to summer of 1940, now you have German mountain troops engaged in Norway in true mountainous combat. Now you’re beginning to see the complexities of the mountains, not even in a winter environment because it’s really from March to June that the German invasion in Norway is happening and they see that there’s a need for this specialized training and equipment and forces to begin to operate and add on to that. Now you get the Italian invasion of Greece in October and November of 1940. So you just see this ever-increasing drumbeat of, it’s not just cold weather, it’s going to be mountainous environments as well. And those things are going to have an impact.

And the world environment at the time is really influencing this project as it develops, right? It’s envisioned as one thing early on. I mean, even the National Ski Patrol presents it as a western, you know, North American defense plan when it’s first pitched, very much like the Finns defending Finland. But by the time the plan really gets going, it’s not seen as we’re defending the Rockies or Appalachians if the Germans invaded the East coast. It’s more seen as we need to be able to operate in any environment around the world if we’re going to participate in this conflict.

As Ad Carter would later recount in the 1946 AAJ, “When the U.S. Army started its rapid expansion in the fall of 1940, the campaigns of the German Gerbirgsjägers in Norway were still fresh in the minds of the public. The mountaineering world realized that the only effective resistance to them had been made by the French Chasseurs Alpins aided by British and mountain trained Poles near Narvik. Troops specially trained for cold weather fighting had already proved their worth in Finland. Soon the Balkan campaign emphasized the importance of mountain troops. Some people remembered the bitter fighting in the First World War in the Carpathians, the Vosges and the Alps, and others recalled the decisive mountain victory of Caporetto, which nearly knocked Italy out of the war.”

In his chronology of the Division, Dr. John Imbrie noted that on September 25, 1940, as Minnie Dole was corresponding with General Marshall, “Members of the American Alpine Club, cooperating with the National Ski Patrol committee, are already at work advising the Army on equipment for winter and mountain warfare.” In particular, he noted that Carter had written a report that anticipated many of the elements eventually incorporated into the 10th Mountain Division.”

Carter’s paper, which was titled “Suggestions about Mountain Troops“, was completed in October. Taking its key observations from the European experiences in the Italian Front, as well as The Winter War, the German mountain troops in Norway, and the ongoing debacle of the Italian invasion of Greece, it moved beyond Dole’s argument for equipping army units with skis and snowshoes toward the establishment of what Carter called a “real” mountain division, trained in both military affairs and mountaineering, that could be deployed in difficult mountain terrain the world over. details the importance of equipment development (lightweight food, sleeping bags, tents, clothing); the need for pack artillery; and engineering groups that could construct portable tramways.

Carter was 27 years old in 1940, and Bob Bates was 29. They were smart, industrious and resourceful, and Carter had likely been conducting research for his paper, with Bates’ help, since spring. As well-connected up and comers in the rarified society occupied by the AAC, they had some pull; more important, they had some pull with people who had real pull.

Bates was a beloved English teacher at New Hampshire’s Phillips Exeter Academy, one of the country’s oldest and most prestigious prep schools. Its school year begins in early September after Labor Day.

“Shortly after returning to Exeter,” Bob Bates wrote in his autobiography, The Love of Mountains is Best, “I had conversations with James Bryant Conant, president of Harvard, about his son Jim, an Exeter student…. Mr. Conant wanted to do a rock climb in the White Mountains and asked if we could all do one together. With my brother’s help, I agreed to take father and son up the “Pinnacle” on Mt. Washington. …The day was successful in more ways than one, because we talked much of the time about how mountain troops could be useful to the American army. Conant was to meet with General George Marshall in a few days and promised to discuss the importance of beginning to train such troops.”

You’ll remember that Secretary of War Henry Stimson was a mountaineer in his youth, as well as a member of the American Alpine Club. Where was his office? Adjacent to that of General Marshall. By the fall of 1940, as they were trying to figure out how to develop America’s expanded army, they were getting the full court press from skiers and climbers alike.

And at that point, the Army’s conception of what a mountain unit could and should become had begun to shift.

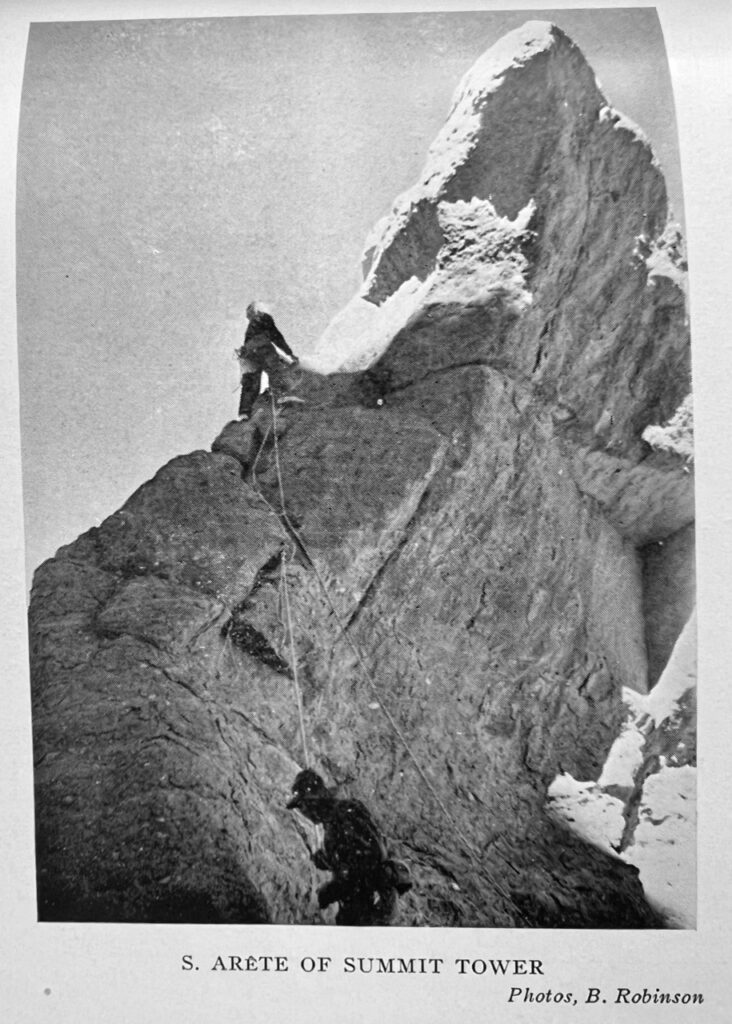

Like Carter and Bates, Bill House was one of the leading mountaineers of his generation. A member of the Yale Mountaineering Club and a graduate of the university’s forestry school, he had established one of North America’s finest climbs in 1936, when he and German emigre Fritz Wiessner made the first ascent of Canada’s Mt. Waddington, a mountain that had turned back 16 expeditions before them. In 1938, House had joined Bates, Paul Petzoldt and Charlie Houston on the first American Expedition to K2, climbing the route’s crux, a break in a great reddish rock buttress that today is known as the House Chimney, in a display of some of the finest climbing ever done at high altitude.

Walter Abbott Wood, Jr. was another young member of the American Alpine Club who had distinguished himself with both his climbing and his professional exploits. A member of the first graduating class of the American Geographical Society’s School of Surveying in 1932, Wood had traveled to the Kashmir-Tibet border in 1929 on a mapping mission, and in 1935 he’d made the first ascent of Mt. Steele, one of the highest and most inaccessible mountains in the Yukon. Together with legendary climbing pioneer and fellow AAC member Ken Henderson, Wood had established the first certification process for American mountain guides in the late 1930s.

The president of the Club was James Grafton Rogers, the founder and first president of the Colorado Mountain Club as well as dean of the Yale Law School. Rogers was longtime friends with both Secretary of War Stimson and Chief of Staff General Marshall.

During an October 25, 1940, meeting of the AAC, Bates, House and Wood suggested that the Club offer the services of its members to the War Department. At around the same time, president Rogers must have written Stimson, because he received a response on November 5 in which Stimson informed him of the Army’s intention to limit its cold-weather operations in the upcoming winter to exploratory ski patrols, which it planned to conduct with the assistance of the National Ski Patrol, and that the training of some units of “Alpine Troops” might take place during the following winter, in which case the Army would take the AAC up on its offer to help.

Sometime after the AAC’s October board meeting, Wood asked Bates to help him set up an exhibition of modern mountaineering equipment for a senior army officer. “The display and the discussion that followed obviously made an impression on him,” Bates would later recall in his autobiography. By then, the Italians were getting their derriers handed to them in the Albanian mountains on a frozen platter by the Greeks, and Army officials were beginning to take note.

And this is when we arrive at what I like to call the Army’s “oh shit” moment.

On December 20, 1940, Colonel Harry Twaddle, the Army’s acting assistant chief of staff, wrote to President Rogers, asking for information on the essential items of mountaineering equipment that could be of use to the army.

“My dear Dr. Rogers,” Colonel Twaddle wrote. “Reference is made to your recent letter to the Secretary of War offering the assistance of the American Alpine Club in any development of the technique and tactics of high mountain warfare which may be undertaken by the Army.” The Army, Twaddle continued, was making a study of the problem, via the exploratory ski patrols that Marshall had just approved; but while said patrols were expected to yield data on the requirements for skis, snowshoes, sleeping bags, special winter clothing, and other items for winter operations in snow, information related to equipment and clothing required for high-mountain operations in the summer time was of interest as well, and “It is in regard to this equipment that the assistance of the American Alpine Club is particularly desired at this time.”

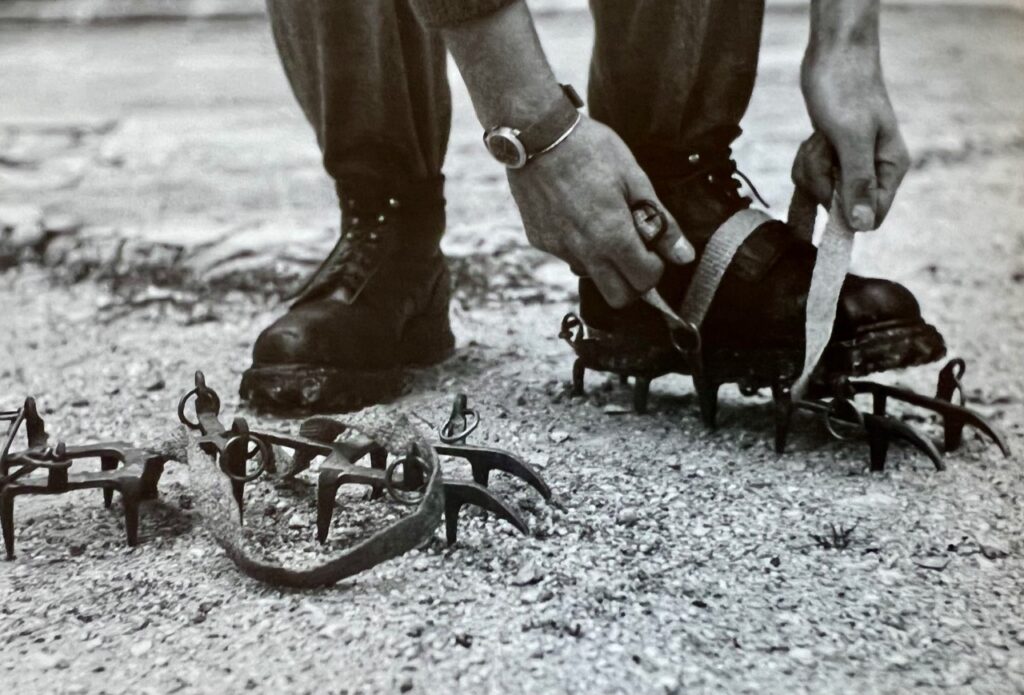

“It is believed that certain special equipment with which the Army is not familiar will be required for such operations,” he continued, and with that, he proceeded to list 21 items—including, as he put it, alpine stocks, crampons, safety belts, special type shoes, and climbing ropes—and requesting that President Rogers provide a brief description of each item’s nature and use; the name and address of manufacturers and dealers from whom the item could be secured; the approximate price range of the item, either wholesale or retail, and, where appropriate, the amount of such items of equipment required, using the Infantry squad of 12 men as a basis. For example, how many alpine stocks would be required for a party of 12 individuals?

“My dear Colonel Twaddle,” one can imagine President Rogers responding. “The American Alpine Club is more than happy to assist. That said, we regret to inform you that nearly every single piece of equipment about which you’ve inquired, including Alpine Stocks, which are more commonly known as alpenstocks and which all twelve members of the infantry squad would be advised to have

in order to navigate steep snow and ice, is made in Italy, Germany or Austria, and as such, given the current circumstances, might prove difficult for America to procure.”

Even John McCown, in his second year of climbing, could have told Colonel Twaddle that in 1940, the best climbers, clothing and equipment came from countries with Alpine traditions. Joe and Paul Stettner had made the first ascent of the Stettner Ledges on the east face of Longs Peak using equipment they’d had sent over from their home in Germany. When Ken Henderson and Robert Underhill made the first ascent of the Grand’s East Ridge in 1929, they did so with Swiss-made, Tricouni-nailed boots, sixty-foot, 7/16-inch Italian hemp ropes and Austrian alpenstocks. In 1936, Bill House and Fritz Wiessner had made the first ascent of the south face of Mount Waddington, using “eighteen pitons, eight karabiners, hammers, 300 ft. of light rappel line,” and a ”very supple” thirty-five-meter climbing rope, most likely made of silk, that Wiessner had purchased from—you guessed it—Germany.

Asking Germany to send along a supply of ice axes, crampons and carabiners that the Army could use to develop an American mountain unit with which to fight the Gebirgsjagers in the Alps—yeah, that wasn’t going to happen.

After careful consideration, H. Adams Carter, Bob Bates, Colonel Twaddle, President Rogers and John McCown had all arrived at a similar conclusion. America, they’d realized, was up a mountain without an ice axe.

[line break]

And that concludes Episode 3 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening.

We’re trying to tell the story of the Division as accurately as possible. To that end, Paul Horton, whose excellent website, tetonclimbinghistory.com, contains photographs of all the Teton summit register entries referenced on this show, points out that Albert Ellingwood and Eleanor Davis made the fourth ascent of the Grand Teton in 1923, not the third as stated in our last episode. He also points out that when, in 1924, Paul Petzoldt retrieved Theodore Tepee’s body from the glacier that now bears his name, wasn’t the first body recovery in the range, just the first that resulted from a climbing accident. If you catch an error, or have additional insights that could add to our history, reach out. We’d love to hear from you.

Special thanks today go out to our new patrons, Peter Breu, Peter Metcalf, Bob McLaurin, Carlos El, Peter Zeising, Adam Clark, Jason Keith, Rod Newcomb, Faith Rand, Mark Sullivan, Daniel Rose, Melanie Schwab and Flint Ellsworth. Patrons are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack because they make it possible to keep the show going. I hope you’ll consider becoming one too.

If you liked the episode, you know the deal: subscribe to the podcast, share it with a friend, give it five stars on your app, and sign up for our newsletter at christianbeckwith.com so you don’t miss an update.

And did I mention that while you’re there you should really click the bright orange button, become a patron and buy me a beer so you can get all the bonus content for this and every episode?

Thanks to our partners, The 10th Mountain Division Descendants, the Denver Public Library, The American Alpine Club and the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, as well to our advisory board members, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt, for their help with this episode and to Dr. Blyth for his assistance in putting this episode together.

Until next time, thanks for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.