In Episode 10 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack, we explore the seismic cultural shift that—driven in no small part by citizen-soldiers like John McCown—enveloped the U.S. Army during WWII. As John and his fellow officers underwent their rigorous training at Officer Candidate School in preparation for their pivotal roles at Camp Hale, they faced the daunting challenge of preparing new recruits in the specialized art of mountain warfare. Drawing from first-hand sources and expert insights, this episode delves into the innovative strategies and leadership skills required to transform the 10th Mountain Division into a formidable force, overcoming traditional military doctrines and embracing the unique demands of combat in mountainous terrain as they reshaped the Army into one of the mightiest forces the world had ever known.

The episode includes interviews with Ninety-Pound Rucksack Advisory Board Members:

- Lance R. Blyth: Command Historian of North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and United States Northern Command (USNORTHCOM); Adjunct Professor of History at the United States Air Force Academy.

- David Little: “living historian” for the Tenth Mountain Division Foundation.

- Sepp Scanlin: military historian and museum professional; served as the 10th Mountain Division and Fort Drum Museum’s Museum Director.

Key Points:

- The draft and the enlistment of citizen soldiers changed the US Army from a rigid, authoritarian, all-volunteer institution into one of the mightiest forces the world had ever known.

- The development of Officer Candidate School (OCS) created an industrial-style assembly line that produced junior leaders to lead the citizen army into combat.

- The innovative Junior Officers’ Plan, which was developed to train officers for the mountain troops and then return them to the unit, preserved invaluable institutional knowledge critical to the mountain troops’ ability to fight in cold weather and mountainous terrain.

- The challenges of adapting the Army’s standard flatland, warm-weather military strategies to mountain warfare was but one example faced by a specialized division designed to fight in extreme conditions.

Featured Segments:

- A vivid recreation of a conversation between John McCown and his peers at Ft. Benning, Georgia, highlighting:

- their takeaways from Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union and the impact of winter on his army’s defeat

- their frustrations with traditional Army tactics and its inability to recognize the importance of specialized training

- their resolve to embody the change they knew the mountain troops would need in order to fulfill its mandate

- An overview of the Army’s transformation from an all-volunteer force into one led by citizen-soldiers like John McCown.

- Detailed analyses of Officer Candidate School, the Junior Officers Plan and the need for a purpose-built encampment for the mountain troops.

Partnership Acknowledgments:

- The 10th Mountain Division Foundation: The mission of the Tenth Mountain Division Foundation is to honor and perpetuate the legacy of the soldiers of the 10th Mountain Division past, present, and future by doing good works that exemplify the ideals by which they lived.

- American Alpine Club: Supporting climbers and preserving climbing history for over 120 years. Learn more at americanalpineclub.org.

- The Denver Public Library: The Denver Public Library: The Denver Public Library’s 10th Mountain Division Resource Center is the official repository for all records and artifacts related to the World War II-era 10th Mountain Division.

- The 10th Mountain Division Descendants: The 10th Mountain Division Descendants: The 10th Mountain Division Descendants, Inc. exists to preserve and enhance the legacy of the WWII 10th Mountain Division and 10th Mountain Division (LI) for future generations

Sponsorship Acknowledgments:

- CiloGear: Makers of the finest alpine backpacks. Visit cilogear.com and use code “rucksack” for a 5% discount and a matching donation to the American Alpine Club.

- Snake River Brewing: Wyoming’s oldest and America’s most award-winning small craft brewery. Discover their beers at snakeriverbrewing.com.

Patron Support:

- A special thank you to our community of patrons for making this research possible. Join us at www.patreon.com/NinetyPoundRucksack to support the show and access exclusive content.

Episode 10: The Old and the New

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and I’m so glad you’ve decided to join us today, because we’re about to explore an aspect of the 10th that’s rarely considered and yet absolutely critical to our story: the culture change that engulfed the Army during World War II, driven in no small part by citizen-soldiers like our protagonist, John Andrew McCown II.

If you’re just joining us, Ninety-Pound Rucksack is the real-time research for a book I’m writing about the 10th Mountain Division and its impact on outdoor recreation in America as seen through the experiences of McCown, a young man who learned to climb in the Tetons, joined the division after Pearl Harbor and rose through the ranks to engineer its signature offensive, the remarkable 1945 ascent of Riva Ridge in Italy’s Apennine Mountains that precipitated the German surrender of italy and hastened the end of the war. The scenes about McCown in this and every episode draw from three tiers of facts. Wherever possible, I rely on first-hand sources, including materials provided by John McCown’s family, genealogical research and papers from the 10th Mountain Division’s archives. Where such sources are unavailable, I triangulate between civilian and military histories, interviews with subject matter experts and the input of our incredible advisory board to help fill in the blanks. Recreations of events are informed by the best available information related to their unfolding as well as original research and personal experience.

I wouldn’t be able to do any of this without the support of our partners, the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the American Alpine Club, the Denver Public Library, and the 10th Mountain Division Descendants, as well as that of our sponsors, CiloGear, and Snake River Brewing.

Any great mountain adventure requires a great pack, and if you’re in the market for the lightest, most durable, best-fitting alpine backpack that money can buy, CiloGear has you covered. My personal experience with the CiloGear Worksack has been nothing short of amazing. It’s comfortable, the materials are bombproof, it never gets in the way of my climbing, it does everything I need it to do when I need it—and the rest of the time, I never notice it’s there.

CiloGear is 100% owned & operated in the US , and if you go right now to their website at cilogear.com and enter the discount code “rucksack,” you’ll get 5% off and they’ll make a matching donation to the American Alpine Club.

The American Alpine Club has been supporting climbers and preserving climbing history for more than 120 years. AAC members receive rescue insurance and medical expense coverage, providing peace of mind on committing objectives. They also get copies of the AAC’s world-renowned publications, The American Alpine Journal and Accidents in North American Climbing, and can explore climbing history by diving into the AAC’s Mountaineering Library. Learn more about the Cub and benefits of membership at americanalpineclub.org, and get a taste of the best of AAC content by listening to the bi-monthly American Alpine Club podcast on Spotify, Apple podcasts, or Soundcloud.

Snake River Brewing is Wyoming’s oldest and America’s most award-winning small craft brewery. I developed a taste for their beers in 1994, the year the Snake River Brew Pub opened here in Jackson. I was one of their dishwashers by night, but by day, I was in the Tetons, and I always reached for a Snake River beer after every adventure. Thirty years later, I still do. Now, with distribution across Wyoming, Colorado, Idaho, and parts of Montana, so can you.

Whether you’re refreshing yourself with an Earned It Hazy IPA or celebrating their 30th anniversary with a Dirty 30 IPA, discover the taste of adventure with Snake River Brewing. And when you’re in Jackson, swing by the Brew Pub for some good vibes, killer brews, and delicious grub. Serving breakfast, lunch and dinner 7 days/week. Check them out at www.snakeriverbrewing.com.

Most of all, I’d like to thank our community of patrons for helping us tell our story. Chances are you’re listening to this episode for free, which is great, but the countless hours of research that went into this episode would not have been possible without our patrons’ support. As our way of saying thanks, we publish exclusive, patron-only interviews and behind-the-scenes content that complement everything you’ll hear on today’s show. If you want to support the show, please go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. For as little as $5 a month you’ll become more than just a listener; you’ll become a crucial part of our storytelling journey.

And with no further ado, let’s dive into our next episode..

[line break]

John McCown leaned back against the narrow metal frame of his bunk and plucked the morning’s Atlanta Journal from his lap. The sound of soldiers’ conversations and the slap of leather soles on the cement floor reverberated through the sparsely furnished barracks. Blackout curtains shrouded the windows. The air smelled of sweat, boot polish and cigarettes.

“Listen to this,” John said, clearing his throat. Above him, Worth McClure poked his head over the edge of the upper bunk. Across from John, Charlie McLane sat perched on his own cot, absorbed in a map of Europe laid out at his feet.

John snapped the paper between his outstretched hands and began reading from the front page. “Russians repel fresh German attacks in Stalingrad.” Worth tilted his head to listen. Charlie, who was still focused on the map, didn’t look up. “Nazis suffer from bitter cold in weakening siege,” John continued. “Russians claim several thousand German officers and men killed in past three days.” He shook the newspaper for emphasis. “It’s the Battle of Moscow all over again.”

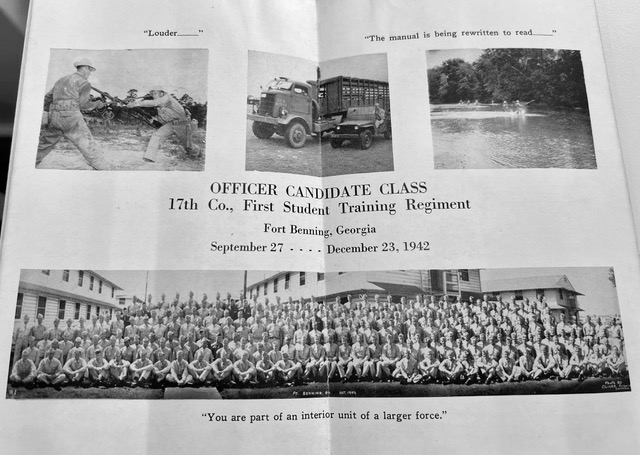

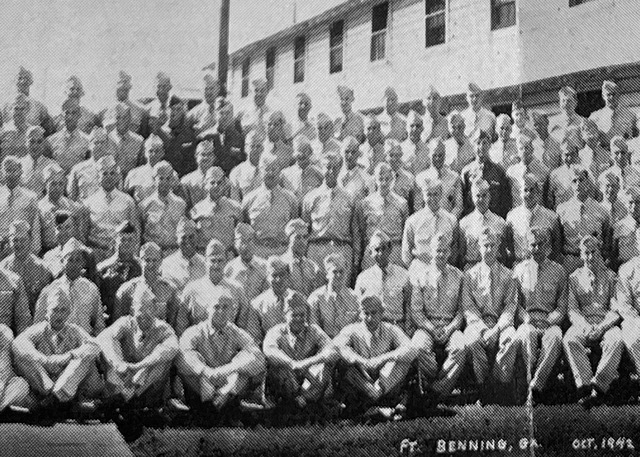

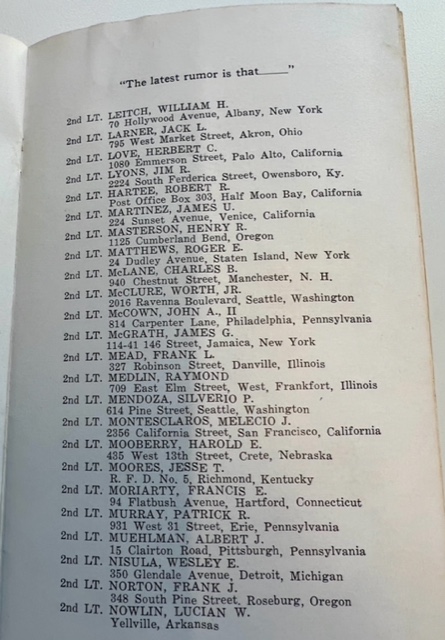

It was nearly 9 p.m. on November 15, 1942, at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the three young men represented the vanguard of America’s wobbly efforts to develop a mountain unit from scratch. Charlie, 22, the first enlisted man to join the mountain troops, Worth, 29, the Rainier guide turned husband, father and insurance salesman, and John, 24, the Wharton-educated mountain climber who’d dropped out of law school to enlist, had met eight months earlier at Ft. Lewis, Washington, as the 1st Battalion (Reinforced) of the 87th Mountain Infantry had begun to assemble under the command of Colonel Onslow Rolfe, a red-headed cavalryman who didn’t know a thing about the mountains. What he did know was people, and he’d selected them for Officer Candidate School at Ft. Benning both because they were natural leaders and because they knew a hell of a lot more about the mountains than he did. They were part of his Junior Officers Plan, an unprecedented arrangement with the War Department that fast-tracked them for OCS, and then— Upon their commission as second lieutenants, the lowest rung on the officers’ ladder—returned them to his command, where they’d be joining him at Camp Hale, the mountain troops’ brand-new base in the Colorado Rockies. Their upcoming orders would be to help Rolfe transform the 4,000 troops of the 87th into a full division of 15,000 men who knew how to climb and ski. Anticipation and anxiety had been coursing through their veins for weeks. While the entire country had been on edge since Pearl Harbor, they were running on a unique blend of adrenaline. The future of America’s mountain fighting capacities lay in their hands, and they knew it.

Since the end of September, they and their classmates had been studying and training and drilling six days a week, from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m., with five-minute breaks between classes and a study period four or five nights a week to top it off. OCS was designed to teach them how to lead an infantry division’s rifle company into battle. To do so, they’d studied everything there was to know about a rifle platoon: its composition, its duties, how it communicated, how it marched, how it moved ammunition forward in combat, how it defended itself in retreat. They’d acted as squad leaders, platoon sergeants, patrol leaders and company commanders, overseeing their fellow candidates as they developed the ability to fight and win a war.

The training had been rigorous, the schedule taxing, the conditions severe. Of the 187 men who had been part of their class at the start of OCS, nearly a third had already been dismissed. Rumors of suicide circulated among the barracks. Worth had seen a paratrooper die when his chute failed to deploy and his jump ended on the training field with a sickening thud. But the three friends had bigger things on their minds: namely, how to reconcile what they had learned since they’d left Ft. Lewis with what awaited them at Camp Hale and the lessons that lay hidden in plain sight in the map at Charlie’s feet.

The map, its quadrangles creased from study, was both a blueprint and an enigma. It depicted the battlefields of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union that had begun June 22, 1941. Three blue arrows soared away from Germany, across Poland and Slovakia and into the massive red area denoting the Soviet Union. The top arrow pointed toward Leningrad in the north. The bottom arrow sped toward Stalingrad in the south. John’s combat knife, which he’d been given by his father, was embedded in the tip of the central arrow, an eighth of an inch from Moscow.

Germany’s invasion of its former ally had been predicated on speed. Between June 1936 and November 1937, Josef Stalin, in a paranoid effort to consolidate power, had executed several thousand senior military officers and removed from the ranks tens of thousands more. In August 1939, Russia and Germany had signed a non-aggression pact, agreeing not to interfere with one another’s military ambitions and to divide the countries that lay between them. The divisions had begun in September with the invasion of Poland, the incident that had precipitated the war. Three months later, the Soviet Red Army had invaded Finland. As camo-clad, cross-country skiing Finnish guerrillas thwarted the advance of the Russian forces, its military ineptitude played out on a global stage, convincing Hitler of the merits of his plan.

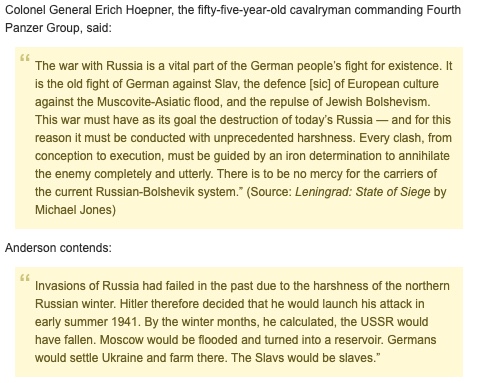

The non-aggression treaty had been a ruse, one that granted Hitler the time he needed to work out the details of his vision. The German peoples were, in his mind, the master race, but to realize their ideological destiny of world domination they needed Lebensraum, or “living space”, and for that they needed land. Standing in the way were the impurities of liberalism, socialism, communism, Bolshevism as well as what Hitler considered to be humanity’s cancerous stains: the gypsies, the Slavs, the homosexuals, the Freemasons, the Jehovah Witnesses, and most of all the Jews. By invading Stalin’s Jewish-Bolshevist regime, eliminating the biologically inferior, the physically compromised and the morally weak, subjugating the Russian peoples that remained, and using the country’s resources to fuel the war against the Anglo-Saxon powers, Hitler would guide the Aryan race to its full potential and purify the planet of its scourges at the same time. All means were justified. Only the end mattered.

Hitler’s belief in Germany’s racial and cultural superiority, coupled with the Red Army’s spectacular display of incompetence in Finland, emboldened him. Overthrowing the Soviet Union was a matter of providence. Spurred on by the success of the blitzkrieg tactics that he’d used to capture France and the low countries in the space of six short weeks, he planned an early summer invasion that would take full control of Russia in two to four months. Given the certainty of victory, there was no need to winterize his army. Why would there be, when he’d be knocking down the gates of Moscow by autumn?

Operation Barbarossa had begun with stunning success. Three million German troops, the greatest land invasion in the history of warfare, had streamed across the Russian border, their advance along the 1,800-mile front unimpeded by Soviet air forces, which had been decimated by the German air force, the Luftwaffe, while still on the ground. Believing Russia’s moral and racial impurities left it vulnerable to defeat— “We only have to kick in the door,” as he put it, “and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down”—Hitler had committed 148 divisions—a full 80 percent of the German army—to the invasion. As the Nazis rolled across Russian territory, their 3,400 tanks supported by 2,700 aircraft of the Luftwaffe, they killed hundreds of thousands of Red Army soldiers. Perhaps more important, from Hitler’s perspective, they began the systematic extermination of Russian Jews as well. Between July and October 1941, German execution squads killed 148,000 Jews in Bessarabia alone. Over a two-day period, from September 28-29, Nazi soldiers killed 34,000 Jews outside Kiev.

And then, the invasion faltered. Why? For one, Hitler had failed to account for the vast distances of the Russian landmass and the difficulty they posed to resupplying his forces. For another, Germany had assumed the Soviet Army had three million men; as the summer’s heat gave way to the cooler temperatures of autumn, they’d captured three million men, and yet countless more continued to pour in from the east. The invasion had prompted Russia to join forces with Great Britain and the Allies. While Hitler paused the advance on Moscow to redistribute forces north and south, Stalin, fortified by Allied resupplies, had redefined and strengthened the front line. At the same time, he’d relocated his factories far behind the lines, in the Ural Mountains, where Hitler and his air forces couldn’t reach them.

All these factors contributed to Hitler’s troubles. But they weren’t why John had placed the tip of his knife next to Moscow.

While Hitler’s advances had slowed, the seasons hadn’t. In October, as the rains swept the land, a quagmire ensued. Tank tracks seized with mud, grinding the German offensive to a halt. When nighttime temperatures began dipping below freezing, the muck of the freeze/thaw cycle further complicated Hitler’s plans. But the coup d’etat the Russians had been counting on was the arrival of winter.

By early November, the German army, lacking winter clothing, began suffering its first cases of frostbite. On November 6, Radio Moscow announced that Germany had lost more than 4.5 million men in the offensive. Two days later, Hitler retorted that the Soviets had lost between 8 and 10 million. The figures were psychological warfare, patent distortions designed to convince friends and foes alike of the inevitability of victory—but the further the temperatures dropped, the more the reality of winter settled in.

When the mercury hit zero, soldiers could no longer dig foxholes. At ten below, their fingers numb from the cold, they could no longer operate their rifles. The disposal of human waste fell apart, and rampant sickness ensued. They needed more clothing to stay warm, so their packs grew heavier. The blizzards arrived, and German tanks with their narrow tracks and low clearance could no longer punch through the deepening drifts. Physical movement through those same drifts became an exhausting nightmare. Fatigue made soldiers more susceptible to injury, and as the exertions burned up energy, their caloric needs skyrocketed.

At thirty below, the focus shifted to survival. Hypothermia became ubiquitous. Fuel spilled on skin resulted in instant frostbite; so did skin on metal. Even when soldiers succeeded in operating their equipment, firing pins shattered, recoil liquids froze in machine guns, and artillery rounds detonated with little effect amidst the growing snowpack. At forty below, rubber became brittle; lubricants stiffened; plastics splintered; fuel lines seized; engines failed to start; and tens of thousands of Russians and Germans alike simply froze to death.

On December 6, the Red Army counterattacked. Stalin had secretly called up 14 divisions from the east; these included Siberian fighters, accustomed to the cold and cloaked in white camo. Their vehicles were winterized; so was their clothing. The Germans, already reeling from winter’s onslaught, buckled under the blow.

The Fuhrer Directives were a series of orders, issued by Hitler himself, that provided strategic instruction on everything from the disposition of military units to the governance of occupied territories. All were binding, to be followed to the letter, and they superseded any other law. Directive 39, which he issued on December 8, 1941, read as follows:

“The severe winter weather which has come surprisingly early in the east, and the consequent difficulties in bringing up supplies, compel us to abandon immediately all major offensive operations and to go over to the defensive.”

Directive 39 was a sham. The only one who had been surprised by winter’s arrival was Hitler. By the time the cold abated and the Battle of Moscow was over, between 250 to 400,000 German soldiers had been killed or wounded. Red Army losses had been even higher, with somewhere between 600,000 to 1.3 million killed, wounded or captured. But Stalin’s willingness to endure catastrophic human losses was absolute, and winter had helped him deliver what the Allied powers, to that point, had been unable to provide: Hitler’s first defeat.

And yet Hitler refused to give up. Deep inside the Russian homeland and strung out along resupply lines, his army’s need for oil was existential. Six hundred miles south-southeast of Moscow on the banks of the Volga River lay Stalingrad, the Soviet Union’s largest industrial center and the river’s key transportation hub. Whoever controlled it controlled access to the rich oil fields of the Caucasus at the same time.

Undeterred by his setbacks in Moscow, Hitler planned a renewed summer offensive to take the oil fields and Stalingrad simultaneously. The city’s strategic value was obvious to both sides, but its symbolic value was inestimably higher to Stalin, for whom it was named. He’d ordered his soldiers to fight to the death in its defense, and, believing they’d fight harder to protect civilians, refused to evacuate its residents as well. By the time the changing seasons caught up with the overextended Axis troops, the siege had devolved into some of the most brutal street fighting the world had ever seen.

And then, as evidenced by the front page news John McCown had read to his friends, winter had intervened once more, and the Red Army, which had waited patiently for its arrival, counterattacked. When the bloodbath was over, they’d killed or captured an additional 100,000 Axis soldiers. Soviet losses were twice that, but they’d repulsed the invaders. And General Winter, as the Russians called the season, had proven pivotal to their success yet again. The battle would mark the war’s turning point, one from which Hitler and the Nazis would never recover.

John put down the paper, swung his long legs over the cot, plucked the tip of his father’s knife from the arrow pointing to Moscow and stabbed it into the heart of Stalingrad. “You’d think the Germans would have learned after last winter. Now they’re getting their asses kicked in Stalingrad too.” His voice was calm but carried an undercurrent of intensity. “It’s as if they still don’t understand the cold.”

Worth shifted forward on the top bunk. His fair-skinned face and red hair were haloed by the single overhead bulb illuminating their conversation. “Soviet resilience is one thing,” he said, “but it’s the winter that’s doing Hitler in.” He paused, then added, “We need to be thinking about that too.”

John left the knife embedded in the paper landscape, lay back on his bunk, folded his arms behind his head, and let out a frustrated sigh. The day’s drills had focused, once again, on tactics that only deepened his dissatisfaction with the Army’s antiquated structure and approach.

Officer Candidate School was America’s answer to the severe shortage of military leaders at the start of the war. It compressed West Point’s four years of curriculum into a grueling three-month sprint out of necessity: to defeat Hitler and the Axis powers, the War Department had determined it needed to churn out more than 7 million new soldiers in two year’s time. Those soldiers needed leaders—hence the training at Ft. Benning. A year earlier, 1,389 second lieutenants had been commissioned through OCS. By the time John and his peers graduated, five weeks hence, more than 50,000 candidates would have been marched through the program.

Like everything mass-produced, the historic expansion necessitated an assembly line approach. And as the ferocious winter dogfights between the Soviets and the Germans underscored, therein lay the problem.

John, Worth, and Charlie had been selected for OCS as much for their mountaineering expertise as for their leadership abilities. The troops under their command at Camp Hale would need a form of training for which no manual existed, yet they’d spent the past two months learning what every other future officer learned at Ft. Benning: how to lead soldiers into battle using flatland, warm-weather tactics. The map spread out on the barracks’ floor illustrated their conundrum: without specialized training, specialized fighting could result in calamitous defeat.

“This is what gets me,” John began, his voice tinged with irritation. “What we’re studying is all but useless for what they want us to do. Just look at Directive 39. We can have the greatest soldiers in the world, but if they don’t understand how to fight in the cold, we’re all screwed.”

Charlie had listened intently, his blues eyes fixed on the map as the other two spoke. Now he sat back, a thoughtful look on his boyish face. “We’re being trained as if we’re preparing to fight in the last war, not the next,” he agreed, his frustration mirroring John’s.

Worth, ever the strategist, dropped an arm over the bunk and pointed at the map. “If it hadn’t been for winter, Hitler might have taken Moscow—and he still might take Stalingrad. We’re going to need to teach more than standard infantry tactics. The new recruits at Camp Hale will need cold-weather skills, winter skills, on top of their alpine training.”

Charlie’s expression hardened with resolve. “That’s just it, isn’t it? We can’t rely on traditional command to understand what we need to do. The Russians lost 50,000 men in Finland, mostly to the cold. If we learned anything on Mt. Rainier last winter, it was that we had to figure out all aspects of mountain warfare—the skiing, the climbing and the cold.”

John straightened, his demeanor intense. “Then we’ll lead by example. We’re the only ones in this goddamn army who know anything about the cold and the mountains. It’s not just about tactics; it’s about fighting with the conditions, not against them.”

He paused and took a deep breath. “If we’re going to get this done,” he continued, “it’s going to be up to us to figure out the way forward.”

The darkness around the barracks deepened, but their conversation kept going, weaving in and out of how they’d shape the training at Camp Hale. They were not just learning how to be officers; they were preparing to be pioneers in a new kind of warfare, where the understanding of how to navigate specialized conditions could determine the outcome of a battle.

Eventually they settled into their bunks, but the low murmur of their voices continued amid the snores of other soldiers. As the importance of their future responsibilities solidified, a bond was forged. Their resolve was clear: they would be the change the army needed.

Ft. Benning was called the “Benning School for Boys” for a reason. They’d arrived as young soldiers. They’d be leaving as men, as officers, and as America’s best hope for victory in the mountains.

[Line break]

The army John and his friends were preparing to lead was a far cry from the one they’d joined at the start of the war. It was engulfed in change, and they were the agents of its transformation.

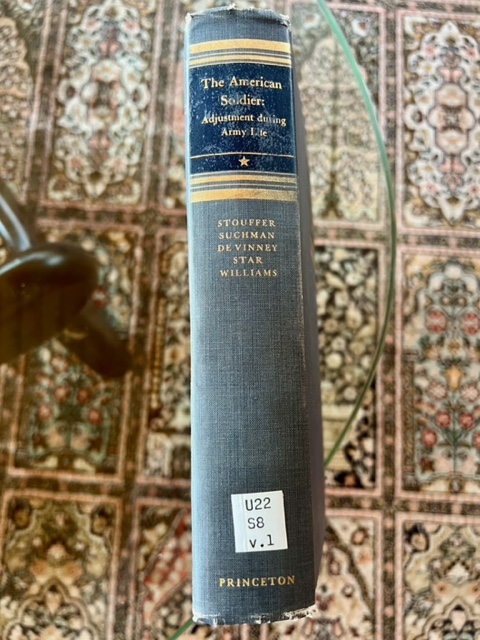

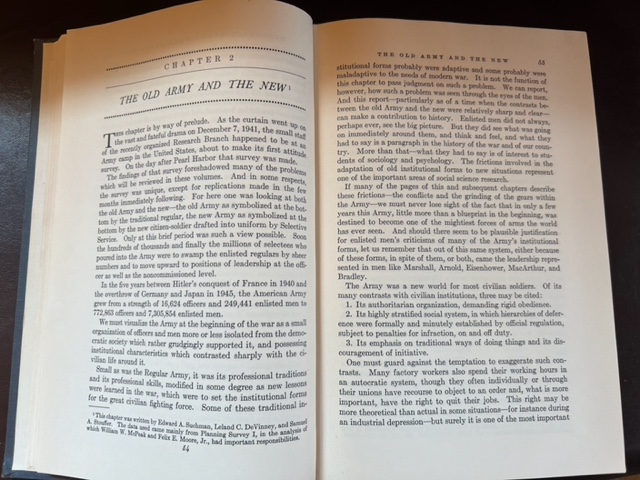

Samuel Andrew Stouffer was a prominent American sociologist who developed groundbreaking survey techniques during the Great Depression. At the onset of World War II, he was chosen to head up the U.S. Army’s Research Branch, which, under his direction, conducted hundreds of surveys and interviewed thousands of soldiers to understand their attitudes and experiences. The results, published in 1949 in a four-volume set called The American Soldier, offer remarkable insights into the Army’s metamorphosis.

“In the five years between Hitler’s conquest of France in 1940 and the overthrow of Germany and Japan in 1945,” Stouffer and his colleagues noted in volume one, “the American Army grew from a strength of 16,624 officers and 249,441 enlisted men to 772,863 officers and 7,305,854 enlisted men.”

The Old Army, or Regular Army, as it had been known, was the product of centuries of tradition: an all-volunteer, authoritarian organization that demanded rigid obedience, operated within a highly stratified social system, emphasized conventional ways of doing things and discouraged initiative. As The American Soldier observed, the Old Army could best be understood as “a small organization of officers and men more or less isolated from the democratic society which rather grudgingly supported it, and possessing institutional characteristics which contrasted sharply with the civilian life around it.”

Before Pearl Harbor, men enlisted in the Army in large part because it offered a dependable job. The longer one’s tenure, the higher one rose through the ranks, and the more money one earned in the process. Merit and initiative played a role in advancement, but they were less important than time served.

As a result, Stouffer wrote, “The Regular Army enlisted man was a youth of less than average education, to whom the security of pay, low as it was, and the routines of Army life appealed more than the competitive struggle of civilian life. By self-selection he was not the kind of man who would be particularly critical of an institution characterized by authoritarian controls. He might get in trouble, of course — there were problems of drunkenness, venereal disease, and AWOL [Absent Without Leave]. But he would be … likely … to accept the Army’s traditional forms as right. This is the kind of soldier to whom the old Army was adapted … on the eve of World War II.”

If anything defines the evolution of American society between the two wars, it’s education. In 1916, 1.7 million students were in high school; 400,000 were enrolled in college. Over the ensuing generation, those figures underwent an exponential leap. In 1940, more than 7 million students were attending high school, and 1.4 million were in college. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act, as the draft was formally known, in 1941 to fill out the Army’s ranks, the selectees came from the civilian population. Accordingly, they included a proportionately high percentage of relatively well-educated young men—who soon found themselves taking orders from officers less well educated than themselves.

Stouffer is quick to point out that education and intelligence levels are not directly correlated, and that socioeconomic factors play important roles as well. “[O]n the average,” he noted, “those who go farthest in school tend to come from higher income levels than those who do not.” That being said, and numerous individual exceptions notwithstanding, he continued, “educational level constitutes a useful sociological index. A group with a large proportion of college men and high school graduates will on the average have more ability and economic opportunity, and will be more likely to possess intellectual values and ambitions, than a group made up predominantly of men who have quit in grammar school or before finishing high school.“

Of the Old Regulars who had been in the Army at least 18 months at the time of Pearl Harbor, an astounding 41% had a grammar school education or less. 34% had some high school education, 21% had graduated from high school, and another 4% had attended college. By comparison, 11% of the new selectees had attended college and 30% had graduated from high school. 28% had some high school education. Only 31% had a grammar school education or less.

America’s entry into the war began a four-year societal transformation so dramatic that even those of us who lived through the Covid pandemic can barely fathom its pace or reach. The kind of change sweeping through the Army in 1942, though, was different. It was culture change, and it was driven by soldiers like John, Worth and Charlie: citizens who either enlisted after Pearl Harbor or were drafted into uniform.

John and his peers were accustomed to operating within a meritocracy, one that rewarded intelligence, initiative and ambition with advancement. Upon entering military service they found themselves plunged into a system antithetical to the one they had known as civilians. It was a tenure-based hierarchy, one in which structured advancement was based primarily on time served and adherence to the chain of command. Rank was determined more by longevity than by skill and performance.

If this weren’t bewildering enough, the new civilian soldiers were being inserted into this byzantine system as privates, at the bottom of the pecking order. And who was charged with teaching them its ways? The Old Regulars, who not only accepted it without criticism and who had, in general, less education than they did, but who also resented their intrusion into its storied order to boot.

The result was as predictable as it was unavoidable: tension, between the old and the new.

“Ours not to make reply,” Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote of the lowly soldier marching into battle in his poem Charge of the Light Brigade. “Ours not to reason why / Ours but to do and die.” While such blind allegiance to doctrine and orders miscommunicated, misconstrued or mishandled by his superiors might have been prevalent in the Old Army, the new citizen-soldier had other ideas. If he were going to be sent into combat as cannon fodder, he wanted to know why—and the answers were often not forthcoming. As The American Soldier diplomatically observed, “The citizen-soldiers, especially the better educated, tended to be less docile than the old-time career enlisted men in accepting the Army’s traditional ways of doing things as right or best.”

Compounding the new recruit’s frustrations was his perception that his bosses assumed he and his fellow selectees possessed a low level of intelligence, and geared their drills and training methods accordingly. The better educated the new soldier was, the more critical he was likely to be of the Army in general and his new bosses in particular.

But there was a flip side to this as well. “Presumably one of the uses of education is to help individuals handle their environment realistically,” Stouffer wrote. As a result, “the better educated were more favorable than others on attitudes reflecting personal commitment to the war.” They were less likely to try to go AWOL or escape their duties through medical leave or discharge, and more likely to evidence what Stouffer called “a higher personal esprit.” They were also more likely to be ambitious, and that meant moving up the ranks. As Stouffer put it, “However much the Army’s system jarred against their democratic civilian habits, the fact remained that they were in the Army, and, therefore, might as well make the best of it. And making the best of it involved becoming an officer one’s self.”

John, Worth and Charlie were Exhibit A in the resulting transformation. They took issue with what they considered to be the Army’s short-sighted approach and its traditional execution. At the same time, they were committed to winning the war, and that meant changing the Army from within. And by the time they were nearing the end of OCS, new recruits just like them were pouring into the ranks by the millions, where they soon “swamp[ed] the enlisted regulars by sheer numbers,” as Stouffer put it, and moved “upward to positions of leadership at the officer as well as the noncommissioned level.”

Enlisted men, noncoms, officers. Privates, sergeants, captains. To follow along in our story, one needs to understand the Army’s vernacular—and for that we turn to Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board member David Little.

[David Little] Before World War II, we were an all-volunteer army and in 1940 we started the draft process that brought in eligible young men who may not necessarily have wanted to be in the army, but they were selected by Uncle Sam to come learn some military skills. And they generally entered as an enlisted man, the common soldier, so that is a private, a corporal or a sergeant. These are the worker bees. These are the guys that swing the hammer to build the barracks. These are the guys that carry the rifle forward to shoot the rifle at the enemy. Those are enlisted soldiers.

The further up you go from private to corporal, you get more responsibility. So as a private, you learn how to fire your rifle, how to march and how to follow orders. A corporal, you learn the basics about giving orders: here’s how you set up your machine gun; here’s how you dig your box hole for your safety. So you’re teaching your privates how to do those basic military functions and the sergeant is in charge of a small unit, a squad of soldiers of eight to twelve men. He’s dealing with tactical command. You go over here, dig a hole; you come over here, set up a machine gun nest; you come over here and get prepared to blow up this bridge. The sergeant can dig the foxhole and make the soldiers dig a foxhole. The captain is the one that has to pick the spot where that foxhole needs to be and what direction you’re oriented to stop the enemy from coming through.

Your non-commissioned officers are generally those corporals and sergeants who are either more experienced or more knowledgeable and can direct the basic soldier on what to do in the field: this is how you prepare your meal. This is how you make your bed roll. This was the guy that took care of you. If you had a mother in the army, that was your sergeant.

Your non-commissioned officer, the officer class, which is your lieutenants, captains, majors, colonels, and generals: they’re the people that have to be able to look at the strategic vision and make decisions there and give orders. More than just dig a hole here, a lieutenant will tell his sergeant, “Prepare a defensive position here. We have to prepare defense across this a hundred yard line so the enemy can’t come through.” They’re looking at a little more strategic view, a little higher view.

And then the captain, he has 200 or 300 people under him. He’s gotta take an even bigger view. And as you advance in rank, your view and your strategic vision has to be bigger.

Your entry level officer, usually in World War II, had some college or was a college graduate, a little more educated and then had gone through officer’s candidate school.

Here’s how enlisted men like John McCown were selected for OCS.

[David Little] As we were building up the army in World War II, we were drafting these young men or getting volunteers and they came in as privates first class—enlisted soldiers. And the senior officers—the captains, the majors—are looking for those talented young men that might have some college education or demonstrated not only the technical knowledge but leadership skills, how to look at the bigger picture and be able to make those strategic decisions that the officer class is expected to make. Your sergeant has to defend a small area. A captain has to defend a much larger area and be able to visualize on a map where he is going and then look at his resources and say, I need four squads over here and I need five squads over here and I need some artillery support. So it takes a different level of thinking, of thought process, to join that officer corps. Not that they’re necessarily smarter, but they’re just thinking on a different level. Not only did they have the technical skills, but they had innate ability or learned ability to be leaders of men.

And as these soldiers were identified, they were pulled out and sent to OCS in Fort Benning and that was a school that taught leadership. It wasn’t necessarily about how to dig a foxhole, but it was more about, “Where do you need to position your foxholes to defend a mile section of the line,” or to see the strategic view of what’s going on.

When John, Worth and Charlie assumed their positions as second lieutenants at Camp Hale, they would be tasked with the leadership and management of their platoons. They’d be responsible for the welfare, training, and tactical deployment of approximately 30 to 50 soldiers. They would be directly involved in developing their combat readiness, overseeing their physical conditioning, tactical drills, weapons proficiency, and ensuring they were well-prepared for mountain warfare. Their roles as platoon leaders would place them at the forefront of nurturing discipline and cohesion among their troops.

They would be responsible for implementing strategies and orders issued by higher-ranking officers, with translating larger military objectives into actionable plans and ensuring that operations were executed efficiently and effectively. They’d be responsible for maintaining robust lines of communication within their own platoons as well as with superior officers and adjacent units in order to coordinate movements and actions on the battlefield.

They’d also be tasked with managing the logistical and administrative aspects of their platoon’s operations. This included ensuring a steady supply of mountaineering clothing and gear as well as ammunition, food, and medical equipment. They would need to handle administrative paperwork, and manage casualty reports and medical evacuations when necessary. Moreover, maintaining the morale and overall welfare of their platoons would require them to balance their leadership responsibilities with a compassionate approach to the personal and professional needs of their soldiers.

You’ll recall that the Army’s Chief of Staff in World War II was General George C. Marshall, the brilliant military tactician whose leadership would prove key to Allied victory. That victory hinged on the ability to turn millions of civilians into disciplined and obedient privates, additional millions into noncoms, and hundreds of thousands more into officers. And for that, Marshall relied on the so-called architect of his army, Brigadier General Leslie McNair, the commander of Army Ground Forces.

As Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board member Sepp Scanlin points out, OCS mirrored General McNair’s vision for building a military big enough, quickly enough, to defeat Hitler.

[Sepp Scanlin] It’s just like the factories that are turning out the new tanks or the new jeeps or the new rifles. OCS is turned into a factory to produce the leadership at the real granular front lines of the army. It’s the industrial creation of junior leaders to lead this volunteer citizen army into combat.

As we’ve pointed out, the entire concept of a specialized division trained to fight the enemy in cold weather and mountainous conditions ran counter to the assembly line approach adopted by General McNair.

The Soviet invasion of Finland, followed by the success of German mountain troops in Norway and the Italian debacle in the Albanian mountains, had forced General McNair to make a concession. He’d approved the 1st Battalion (Reinforced) of the 87th Mountain Infantry at Ft. Lewis as a test force, but he was still convinced the best way to ramp up the Army was to make every division the same, and then tweak it as circumstances demanded.

The War Department had assigned Colonel Rolfe command of the 87th because he’d been born in New Hampshire, epicenter of American skiing, and thus was assumed to know a thing or two about the mountains. He didn’t—he’d moved away from the state at age six, and his mountaineering experience consisted of a few hikes in Latin America at the end of the ‘30s; but as he furiously tried to figure out just how to go about standing up a mountain unit from scratch, even he could tell he had a problem. Or, more accurately, three problems.

In late 1941, the National Ski Patrol System had signed a contract with the War Department to recruit, screen, and approve volunteers for the test force. It marked the first and only time in our nation’s history a civilian organization had been contracted to do so, and by the time Colonel Rolfe arrived at his post at Ft. Lewis, the National Ski Patrol System had begun funneling the so-called “three-letter men” to him via its system of three letters of recommendation, with captain of the Dartmouth Ski Team Charlie McLane as its first recruit.

In the months following McLane’s arrival, skiers had begun joining the test force in a steady stream. There was a reason for this: skiing’s popularity had exploded in the preceding five years, in no small part thanks to the advent of mechanized lifts, and the National Ski Patrol System could pull from dozens of ski clubs and collegiate teams scattered around the country to help fill the ranks.

Problematically, the mountain troops needed to know more than how to get on and off a ski lift. They needed to be able to navigate mountain terrain in all conditions, carry heavy loads over steep slopes in summer as well as winter, ascend rock and ice while laden with artillery, raise and lower loads up and down cliffs, rappel wearing heavy packs, navigate by map, compass, and altimeter, and survive under the stars in all conditions. These skill sets were the province of the mountaineer, and given the country’s tiny number of expert climbers, they were in short supply.

This brough Rolfe face to face with what we will call Problem #1: paradoxically, the mountain troops lacked mountaineers. The number of experienced alpinists in the country was miniscule to begin with, and the challenge of recruiting them into the 87th was exacerbated by age restrictions and the fact that other branches of service were already poaching top talent. Which led Rolfe to Problem #2: even if he could find seasoned mountaineers, hand pick the best of them for OCS and send them off to become officers, they had to be returned to his command or he’d lose their specialized skills to other units—and Rolfe’s needs were diametrically opposed to the Army’s standard operating procedure.

Solution: the Junior Officers’ Plan.

Here’s Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board member Lance Blyth.

[Lance Blyth] The earliest reference I can find to [the Junior Officers Plan] was in April of 1942, where Rolf with a couple months of ski training experience under his belt, suddenly realized that this was not a one-off—that he needed officers to supervise this training. And he basically went back to the Army and said, go out and help find people. And it takes a while.

As you’ve pointed out, the American Alpine Club was offering help this whole time. They’re like, Hey, how can we help? How can we help? Finally, in the summer of 1942, the Adjutant General of the Army—and that’s who’s in charge of personnel—sends a letter up to the American Alpine Club saying, “Can you help us find men who have the skills and the qualifications?” We can enlist them if they serve their three months, and then they can apply to go to officers candidate school and if they qualify, they will go. And if they pass, we will return them back to the mountain troops. This was not the standard Army way of doing things, but it was a special deal to try to get men who knew what they were doing, but to try to get people like McCown.

Now, there were a lot of men in the mountain troops who, like McCown, could have applied to OCS at any point after their initial three months were up but didn’t want to, ’cause they didn’t wanna leave the unit. They didn’t wanna leave their buddies, they didn’t wanna leave the mountains. And this allowed a lot of men who otherwise wouldn’t have gone, would’ve refused, to go ahead and go knowing they would come back.

So what Rolf had is he had a memo number with a date on it telling of this decision. He could then use that memo number to say, no, I’m gonna send these guys to you and you’re gonna send them back. It says right here, you have to do it. And he starts doing that very early. He takes, you know, Charlie McLane is one of the first guys to show up for the first battalion of the 87th Mountain Infantry. He’s one of the first guys to go to Officers Candidate School. And so the AAC collects up more names, gets more people identified… and that’s the initial tranche of men going to Officers Candidate School in 1942 and returning back to the mountain troops.

Thanks to the Junior Officers’ Plan, John, Charlie and Worth would graduate from OCS on December 24, 1942, and then be returned to Colonel Rolfe to help him train his new recruits—and, in the process, to change the Old Army into the New. But yet another complicating factor lay before them: the yawning social chasm that separated them from their former peers.

“Few aspects of Army life were more alien to the customary folk ways of the average American civilian,” Stouffer and his colleagues wrote, “than the social system which ascribed to an elite group social privileges from which the non-elite were legally debarred and which enforced symbolic deferential behavior toward the elite off duty as well as on duty.” It was, and remains, a chasm so vast, Stouffer referred to it as a “caste system.”

Upon their graduation as second lieutenants, John, Charlie and Worth would receive higher pay than the enlisted personnel under their command. They would live in separate quarters. They’d have access to officers’ clubs, dining rooms, and recreational areas—exclusive facilities from which enlisted soldiers were banned. They’d wear distinct uniforms and insignia that denoted their rank and status, setting them apart visually from their troops. They’d hold higher social status within both military and civilian society, and would be accorded greater respect and deference by peers and subordinates alike. Personal staff would be assigned to assist them with daily tasks, enhancing their efficiency as well as their comfort.

Separate rules and separate classes might seem like an odd approach in a time of war—but, as Sepp Scanlin points out, the military has its reasons for keeping officers and enlisted men apart.

[Sepp Scanlin] A soldier who is taken out of a unit that is sent to this school that is now sent back—he is now in charge of his peers. You went from being one of the guys to now potentially telling the guys to assault that hill that may cause their death. And these are the same guys that you went drinking with, you went partying with. They know your goods and your bads. That is a very difficult transition.

Hence the caste system.

All of these factors were at play as John, Charlie and Worth were having their conversation under the bare lightbulbs of their Ft Benning barracks. Thanks in no small part to citizen soldiers like them, the chaotic beginnings of the Old Army’s transformation into “one of the mightiest forces of arms the world has ever seen” was underway. But if they were to teach their soldiers the art of mountain warfare, they needed more than just official sanction to do so. Which brings us to Rolfe’s third problem.

When he’d been assigned to the 87th, Colonel Rolfe’s official mandate had been to “develop the technique of winter and mountain warfare and to test the organization and equipment and transportation of units operating in mountainous terrain in all seasons and in cold climates in all types of terrain.” It didn’t take a genius to understand that flat, rainy Ft. Lewis wasn’t going to cut it. What Rolfe needed was a proper mountain camp—and on November 15, 1942, the day John was reading the newspaper article to Worth and Charlie at Ft. Benning, just such an encampment was opening for business at 9,200 feet in the Colorado Rockies. It would come to be known as Camp Hale, and its origin story is as remarkable as it is important to our tale—which is precisely why, dear listener, we’ll explore it in all its glorious detail with our next episode.

[line break]

And that concludes today’s episode. Thanks for listening.

A big round of thanks goes out to our sponsors, La Sportiva, CiloGear and the Snake River Brewery; our partners, The 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the American Alpine Club and the 10th Mountain Division Descendants; and as always our advisory board, Lance Blythe, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid and Doug Schmidt.

We are indebted as always to our community of patrons. A warm welcome goes out to our newest members, James Brady, Mark Udall, Climbing Sam, Guy Cherp, Jim Carr, Kris Foote, Tim at HeliResources, Ethan Hathaway, Tony Burns, Alex Sebastian, Seda Salar, Marian and Lance, Dwight Frankfather, Jesse Rounds, Thor Johannessen, David Rikert, Bradley Nicholson, Nick Frichione, Matthew Stewart, Zane Elliott, Kent Diebolt, Steve Draper, Rich Lesperance, Ryan M, Peter Gold, Greg and Lu Anderson, and Jim Pace.

If you’d like to be part of the community, simply go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. While you’re there, pick up a Ninety-Pound Rucksack baseball cap, water bottle or t-shirt so you can show your friends what you’re listening to, sign up for our newsletter so you never miss an update, and become an active part of our story.

Until next time, thanks again for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.