This episode explores how the 1939 Soviet invasion of Finland catalyzed the creation of the 10th Mountain Division… with a little help from the National Ski Patrol System, the United States Army, and a couple of twenty-something climbers from The American Alpine Club.

Thank you for being a patron of the show—you are the heart of Ninety-Pound Rucksack.

Your support allows us to pursue the show’s journalistic and educational objectives. In return, you receive access to all Unabridged content on this page, including this exclusive interview with Professor David Murphy, the author of The Finnish-Soviet Winter War 1939–40: Stalin’s Hollow Victory, on the Winter War:

If you haven’t already, please consider becoming a patron. Our goal with Ninety-Pound Rucksack is to inform and inspire the public about the Division’s living legacy. Patrons make that possible. In return, they receive access to all Unabridged content.

The Winter War: Episode 01 unabridged

See here for an overview of the characters mentioned in this episode.

More than 3% of the world’s population, dead. Millions of people around the world, displaced from their homes. Much of Europe, Asia and parts of Africa, reduced to rubble. Some of the world’s greatest cities—Berlin, Prague, Dresden, Tokyo—destroyed. The British and French empires, gone. Germany and Japan, conquered and occupied. An “Iron Curtain” separating West and East. The dawn of the nuclear age, and the Cold War. The formation of NATO, the dissolution of the “Old World,” and the rise of “the American Century.”

World War II was the deadliest war in history, the most destructive war in history, the most expensive war in history. It grew out of the aftermath of World War I, the so-called Great War, when the victorious Allies—the United Kingdom, France, United States, Japan, Italy and more than two dozen other nations—forced the defeated Central Powers—Imperial Germany, the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires—to sign the Treaty of Versailles. The accord required Germany to admit its role in starting the war, dissolve its military, relinquish its lands and pay reparations that plunged the country deeper into financial ruin. Coupled with the economic depression that swept the world in the late 1920s, it paved the way for the political rise of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, an anti-semitic, anti-communist, far-right nationalist group that would come to be known as the Nazis.

Hitler harnessed the national sense of despondency precipitated by the Treaty of Versailles into an engine for his personal vision, one of a new racial order in Europe dominated by the German master race. To achieve it, he secretly began re-militarizing his country the moment he maneuvered his way to the position of Germany’s Chancellor in early 1933. His intentions were known to Britain and France, the continent’s reigning powers; but, exhausted by the privations of the Great War, they lacked the will to respond to German violations of the Treaty with force, and instead adopted a policy of appeasement that greeted each new German transgression with toothless protests. The League of Nations, an international organization established in 1919 to keep world peace, was no help either: it proved as ineffective in countering Hitler’s advances as it was Japan’s growing military aggressions in Asia.

On March 16, 1935, Hitler denounced the Treaty’s military clauses and began immediate general military conscription in Germany. The act was met on the Continent with verbal protests and nothing more.

On March 7, 1936, he sent more than 20,000 German troops into the Rhineland, a strip of western Germany that borders France, Belgium, and the Netherlands and that had been demilitarized by the Treaty. Britain and France responded with hollow outrage.

On October 23, 1936, Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy signed a nine-point protocol in Berlin that formalized the two countries’ alignment and cooperation. When Italian leader Benito Mussolini declared that all other European countries would thereafter rotate on the Rome–Berlin axis, the term “Axis” was born.

On March 12, 1938, German troops marched into Austria, Hitler’s country of birth, to annex the German-speaking and more-or-less willing nation on behalf of the Third Reich—successor, in Hitler’s imaginings, to the earlier Holy Roman and German empires. As the tepid reaction to the annexation proved, the British and French governments were set on avoiding war at all costs.

On September 30, 1938, under the banner of “peace in our time,” Great Britain, France, Italy and Germany signed the Munich Agreement, which permitted the German annexation of the Sudetenland, the Czechoslovak borderland area where more than three million people, mainly ethnic Germans, lived. In doing so, it handed Hitler the keys to Nazi expansion. The Sudetenland held more than 66 percent of Czechoslovakia’s coal, 70 percent of its iron and steel, and 70 percent of its electrical power. Without those resources, the Czech nation had no means to defend itself from German subjugation.

Emboldened by the world’s failure to act, on March 16, 1939, Germany cast aside the terms of the Agreement and occupied the remainder of Czechoslovakia.

One of the philosophical cornerstones of Britain and France’s policy of appeasement was the belief that a stronger Germany would help curb the spread of Communism engendered by the Soviet Union, its mortal enemy. One can understand the world’s surprise, then, when on August 23, 1939, the two countries signed the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, agreeing to take no military action against each other for the next 10 years.

One week later, on September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Britain, France and other Commonwealth nations had no choice but to declare war, which they did on September 3. The Second World War had begun in Europe. Two weeks later, the Soviet Union invaded Poland. On October 6, Germany and the Soviet Union divided and annexed the entire nation.

And then, on November 30, 1939, this happened.

[Radio Broadcast]

There is warfare tonight between Russia and Finland. The Columbia Broadcasting System presents an analysis of these events by Elmer Davis.

The Russian attack on Finland seems to be regarded the world over as the most indefensible of all such actions that the totalitarian states have committed in recent years. The Vatican City newspaper speaks of a worldwide wave of indignation over Bolshevism’s new aggressive policy. And from the dispatches we have received from all over Europe and from Washington as well, this seems to be no overstatement. Violent reaction to this in England and France and in the Scandinavian countries above all, where they are horrified by this attack on another Scandinavian country, and uncertain if they may come next. Only the Germans content themselves with saying that Russia must have an outlet to the sea. And of course, the communist explanation of this, as I have received it in a number of letters, is that this is not aggression, it is not imperialism—that the Russians, if they go into Finland, will be doing so only for the purpose of liberating Finland.

The nonaggression pact between Germany and the Soviet Union was known as the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact for the two foreign ministers—Joachim von Ribbentrop and Vyacheslav Molotov—who signed it. In addition to allowing Hitler and Stalin to pursue their respective agendas, the pact contained a secret protocol. Russia had conquered Finland in 1809, and the country had been an autonomous Grand Duchy of Russia until it declared independence in 1917. Joseph Stalin wanted it back. Secretly, he wanted a buffer against Nazi Germany’s expansionis as well.. The pact relegated Finland to the Soviet sphere of interest.

Finland’s distrust of Russia was born of familiarity. In 1920, to protect itself, the country had begun constructing the Mannerheim Line, a defensive fortification on the Karelian Isthmus, the strip of land between the Baltic Sea and Lake Lagoda that formed a border between the two countries. It remained unfinished when the Soviet army invaded, and the Russians planned to simply use their vastly superior numbers to break the Mannerheim line, head west toward Helsinki, Finland’s largest city, capture it and win the war.

Stalin had a reason to be optimistic: the plan, on paper, looked good. Russia’s population in 1939 was 170 million. Finland’s was barely more than three and a half million. The Russian army was 1,800,000 strong. The Finns had 350,000 soldiers at most. The Russians launched their invasion in four separate thrusts comprising 450,000 soldiers, a number they would ramp up over the course of the war to more than a million. The Russians had thousands of serviceable aircraft; the Finns had 80. The Soviets had thousands of modern tanks; the Finns had fewer than 20. Russian soldiers had all the artillery the Red Army could muster. The Finns had some light machine guns, some heavy machine guns, and some modern anti-tank weapons, but not enough, all of which dated to the first World War.

Expecting a quick confrontation, the Russians went so far as to bring along brass bands for the victory parade that would follow.

But the Russian forces included marginally employed, city dwelling factory workers from Leningrad who had been conscripted at short notice. They weren’t trained, particularly in outdoor survival, and they were not equipped for winter conditions, particularly in the Arctic. They didn’t have winter clothing, or cooking facilities, or sheltering capacities — and, importantly, they didn’t use winter camouflage.

While vastly outnumbered, the Finns had certain advantages. Finland is heavily forested, and riddled with lakes and rivers, and the Finnish cultural pastime is deeply rooted in the outdoors. Cross-country skiing, skating and hunting were Finnish national traditions, in cities as well as the countryside. The entire population, male and female, embraced the outdoors, in winter as in all months.

Finland’s permanently constituted army was outfitted with a Finnish model bolt-action rifles that were better than the Russian version. Their clothing, including hats and shoes mitts, were camouflaged white. They painted their equipment white as well.

Finns who were activated as reserves comprised the civic guard; they received bolt-action rifles, white camouflage outfits and a national badge on their hat to identify them, but otherwise outfitted themselves. In some ways this was a good thing, because they used their own hunting and skiing set-ups, ones they knew and trusted.

The Red Army invaded at the start of the Finnish winter when the lakes are frozen, the rivers are frozen and the deepest recorded temperatures are minus 40 Celsius. Above the Arctic circle, the land was entering into complete darkness.

The Finns operated in small units, and they knew how to take care of their troops. Every company had the facility to provide hot tenting. If somebody came back from the line, he could get a hot meal and a hot drink and enjoy a rest in a heated area. In some cases, the Finns even built ad hoc saunas, so their troops could not only keep warm, they could enjoy the comfort of the national obsession at the end of a long, hard day of killing Russians.

The Russian system was centralized. Wherever there was a battalion, there was a battalian field kitchen. Once the Finns started targeting them, the Russian soldiers were not only cold: they were also starving. If a field kitchen got taken out, nobody got fed.

The Finns would also do anything to protect their land. When the Russians started invading, the Finns employed a scorched-earth strategy, killing their own livestock and laying waste to the countryside until there wasn’t so much as an outhouse for the Russians to shelter in.

Walk us through the invasion itself. Are there any actions that help illustrate the Finnish tactics?

The Russians lumbered into Finland in early December in mechanized columns with a cavalry mentality, sticking to narrow roads that had few or irregular turning points and that often were adjacent to lakes and rivers and forests. In many cases the forests came right to the edges of the roads. The Finns would maneuver close to the Russian columns, often at night, skating along the frozen lakes and rivers or skiing up through the trees, attacking, and then disappearing back into the woods. They wouldn’t dig in unless they were back behind tree line, so the Russians couldn’t synchronize their artillery onto their positions, and they couldn’t use their superior air power to provide support from above. Without camo, they were easy to target. If the Russians tried to pursue the Finns on the frozen lakes and rivers, the Finns would blow them up and drown them.

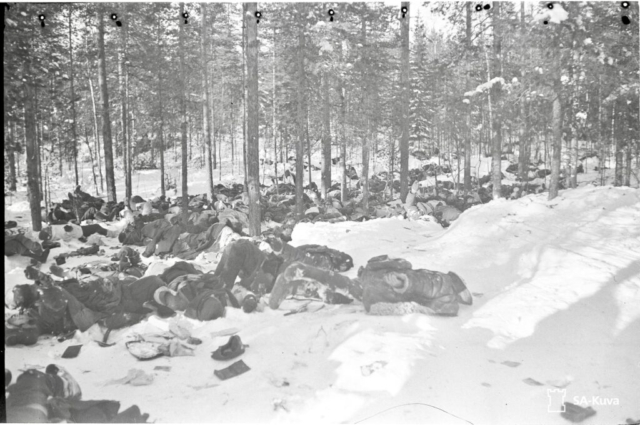

One of the Finnish tactics was to break the long, drawn-out Russian columns into smaller parts they called motty, which is a Finnish measure of firewood. Using roadblocks, they’d divide a column into pieces, then destroy it bit by bit.

In early January, 1941, the 8,000-person Soviet 44th rifle division was traveling to the aid of another Soviet unit that had become trapped deep within Finnish territory. To get there, they advanced west along a narrow road in the middle of the country known as the Raate Road.

The Russian division was crossing a lake when they hit a Finnish roadblock, which stalled its advance and left it stretched out and exposed. The Finns began breaking it up into motty. Over the course of a couple of weeks, often under cover of darkness, they would ski up and set fire to tanks, lobbing molotov cocktails into tank cockpits and melting back into the forests. By the time they were finished, the entire Soviet division was gone.

Psychological warfare

The Finns applied the art of psychological warfare, too. The Russians would put out sentries at night only to find them either dead or missing the next morning. The next night they’d put out more sentries. The Finns would sneak past them into camp. In the morning, Russian soldiers would wake up to find the man next to him dead in his sleeping bag. The Finns went so far as to post frozen Russian bodies as signposts: this way to Helsinki.

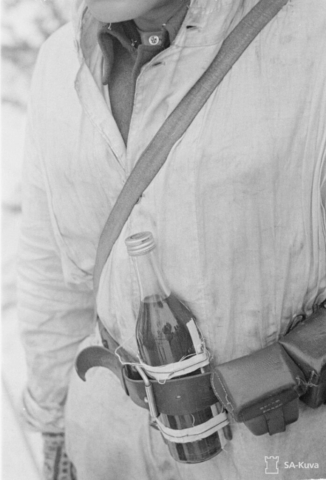

Molotov cocktail

Another innovation the Fins added to their bag of tricks was the Molotov cocktail. The inception of the device dates back to the Spanish Civil, but the Finns took it to a next level, naming it after Russia’s Foreign Minister, who had declared over Soviet radio that the incendiary bombing missions over Finland were actually airborne humanitarian food deliveries of bread. The Finns’ “Molotov cocktail” was thus “a drink to go with Molotov’s food.”

The beauty of the Molotov cocktail was, and is, its simplicity: a bottle of fuel, partway filled and sealed with a cloth wick that doubles as a fuse. Light the fuse, throw the bottle, and when the bottle shatters on impact, the fuel ignites. The Finns perfected the cocktail, refining the recipe to create a sticky napalm-like slurry, and adding a pair of wind-proof matches to the sides of the bottle that they could light before throwing. They went so far as to develop a kind of a contact charge that they taped onto the outside of the bottle so they didn’t have to light anything: just throw it and the contact would ignite the whole thing. The Finns used their cocktails so effectively the Russians targeted the factory where the bottles were being made.

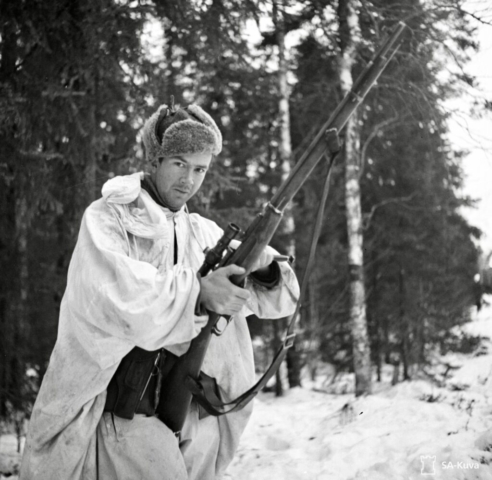

There’s something else remembered from the winter war as well: the most successful sniper in military history.

Simho Häyhä, who lived in rural Finland, was in many ways the epitome of the Finnish resistance. Immensely self-sufficinct in all seasons and all kinds of weather, and an excellent shot, he could survive by himself for days on end. Activated as a reservist, he operated alone, without a spotter. He used the standard infantry rifle, which is not scoped, and stalked the Russians in full camoflauge that included a hood and face mask. Skiing silently through the woods on skis, the only things showing were his eyes. He would sneak up on an end of a column and gradually take it out shot by shot from 100 to 200 yards away. For really close work of 50 yards or less he used a submachine gun of Finnish designed called a Suomi. By the end of the war, he’d registered more than 500 confirmed killed.

But the Finnish guerilla tactics could only hold off the might of the Red Army for so long.

In January 1940, after the disastrous start, Stalin appointed a new commander, Semyon Timoshenko, to head up the campaign. Timoshenko immediately began to modernise the Army, increasing the production of tanks and improving both artillery and close-air support. He brought in better trained toops and better trained NCOs and reintroduced the traditional harsh discipline of the Tsarist Russian Army. He also began to rehearse breaking the Mannerheim line.

By February 1940, the Finnish Army was exhausted and the Russians, fortified with more equipment and fresh, better-trained troops, broke through the Mannerheim line. On March 12 , 1940, Finland was forced to sign the Treaty of Moscow, which ceded 11 per cent of its territory to the Soviet Union.

Impact of Finnish resistance on global and American considerations of a mountain unit

What was unique about the Winter War was that it played out before a global audience. Going into the war, Britain, France and the rest of the world had watched the gigantic Red Army and Hitler’s blitzkrieg tactics in Poland with awe. As the tiny Finnish Army held off one of the leaders in mechanized warfare through the winter months, the mood shifted. The Finns inspired the world.

In America, some 300 civilians, mainly Finnish Americans, had embedded to fight with the Finns. American journalists were embedded as well, and an American military mission in Helsinki reported back through military channels. As word of the Finnish exploits came back to the US in print and in newsreels, a collective realization dawned.

In early 1940, the future was wide open. Would the US enter the war? Who would we be fighting, and where? Would the Russian-German pact continue? Would we be fighting Russians in Alaska? If so, we needed troops who could operate in cold-weather environments. Only by marrying the capacities of moving and surviving in arctic conditions onto standard military training could we develop cold-weather capacities like those of the Finns—and that opened the way for the 10th Mountain Division.

This is where the prevailing narrative about the 10th’s origin story begins, and it most often begins with a voluble, bespectacled skier who, in 1938, had helped put together the country’s first ski rescue organization: the National Ski Patrol System. His name: Charles Minot Dole.

We’re telling the story of the 10th with the help of an advisory board of the division’s foremost experts. McKay Jenkins is one of them. Jenkins is the Cornelius Tilghman Professor of English, Journalism and Environmental Humanities at the University of Delaware and the author of, among many other books, The Last Ridge: The Epic Story of the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division and the Assault on Hitler’s Europe. I’ve asked him to tell us about the man commonly credited with the division’s formation—a man known universally as Minnie Dole.

[McKay Jenkins interview]

[McKay Jenkins]: Minnie Dole was a classic blueblood New Englander. He was a graduate of Phillips Andover Academy, which is a very blueblood old prep school. He then went to Yale, where he was a Whiffanpoof, which is one of the famous a capella groups, and he was such a good singer, that he was actually offered a professional singing contract: he turned it down. And that position was given to Rudy Vallee, who went on to become a very famous crooner. So Minnie Dole came from a very, very solid New England establishment family and went to New England establishment universities. And by virtue of that he was plugged into a lot of what we would now call kind of old-boy networks—like, he knew people in politics, he knew people in business, he knew people, in his case, in skiing.

In February 1940, an apres-ski gathering of four friends—Minnie Dole; Roger Langley; Robert Livermore; and Alex Bright— took place at an inn in Vermont. Some assert the meeting’s location was Manchester’s Orvis Inn. Others argue it happened at Johnny Seesaw’s Inn near the small town of Peru after a race on Bromley Mountain. Still others suggest that the conversation began at Johnny Seesaw’s and continued later that evening at the Orvis Inn, where men were likely lodging.

What is beyond dispute is that the four friends were emblematic of the well-educated, well-connected men at the forefront of the nascent sport, which had somewhere between 500,000 and one million active practitioners. Livermore and Bright had been members of the 1936 Olympic US Ski Team. Langley was the president of the National Ski Association. Two years earlier, he and Dole had conceived of the National Ski Patrol System as a response to the growing number of accidents on the slopes. The ascot-wearing Dole was now its director. You can almost hear the sound of the logs crackling and smell the pipe tobacco as Minnie and his mates discussed the Finns’ ongoing actions against the backdrop of the growing hostilities in Europe.

The reason this came up is that there were newsreels in movie houses all across the country that were showing black and white news footage of Soviet tanks moving through the icy Finnish countryside, and then Finnish skiers—I should note, importantly, cross country skiers—but Finnish soldiers on cross country skis or even at times on ice skates, skiing or skating through the Finnish forests, and launching things like Molotov cocktails or even something as simple as like taking a big stick and jamming it into the treads of Soviet tanks, disabling the tanks or shooting the Russian or Soviet soldiers and then disappearing into the woods. And I’ve always thought that American movie goers would have seen that imagery and thought to themselves this is what the American Revolution might have looked like, a bunch of ragtag American soldiers fighting the British in the woods, coming in, sniping, disappearing. Meanwhile, the British are marching in lockstep down the road and getting picked off.

These guys were not mountaineers, they are skiers. So they thought, well, what we can contribute to this is a big network of people because they had already organized the National Ski Patrol at all the ski resorts in New England. And they also had this Ski Patrol Rescue Training, and they knew everybody that was doing this. They start working there, their networks of people trying to get into the War Department, trying to get an audience with the Secretary of War, with the Army Chief of Staff, trying to lobby for the creation of something brand new.

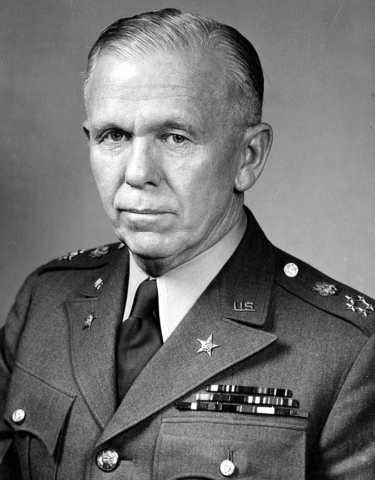

A quick but important aside, one we’ll circle back to shortly. In 1939, The Chief of Staff of the US Army was General George C. Marshall, a brilliant military tactician who would soon go on to oversee the largest military expansion in U.S. history.

The secretary of war was Harry Woodring, a strict non-interventionist who was opposed to American entry into the war. This so irritated President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that he appointed an outspoken interventionist, Louis Johnson, as Woodring’s assistant. Quickly at odds, Woodring and Johnson soon refused to speak to one another. On June 20, 1940, Roosevelt would put an end to the matter by firing Woodring and replacing him with Henry Stimson, a long-time American statesman and Republican politician who had served as Secretary of War under President William Taft and Secretary of State under President Herbert Hoover.

And this is worth listeners thinking about because these were civilians, proposing a radical new set of American soldiers at a time when war was right on the horizon. It was a very brash thing to do. These were not military advisors; these were civilian skiers. So the first response from a lot of the military senior staff was to be, you know, grateful for their patriotism, and they sort of patted them on the head and said, thanks for your eccentric idea but we got this.

There was a reason for the military’s luke-warm response. In 1940, America’s entire military consisted of fewer than 200,000 soldiers. Developing a specialized and unprecedented mountain warfare unit—especially one composed of civilian skiers and climbers—was a tough sell, especially when the Army needed to ramp up its overall numbers ASAP.

But Minnie Dole was really kind of relentless in his lobbying, and he and several of his colleagues, they kept on pounding the pavement, writing letters to Henry Stimson and writing letters to George Marshall and trying to get an audience. And over time, they wore down, I guess you could say, they wore down the resistance in the military establishment and finally, I think it was October 1941, that Henry Stimson and George Marshall agreed to formulate something known as the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment. And a couple of weeks later, November 15, that unit was formed. And then three weeks later, Pearl Harbor happened and the United States entered the war. And suddenly, it’s game time. So what’s interesting about this as it evolved is, once Japan was involved, that opened up the other vulnerable point for the United States, which on the West Coast, which meant the Aleutian Islands. The fear was that if the Japanese were to invade the United States, they would probably hop across the Aleutian Islands, come in through Alaska, and come in down to the continental United States. And you can see the parallel here: in both cases, the Russians or the Germans coming from the northeast, or the Japanese coming from the northwest, both entry points were northern and cold environments. And so soldiers trained in Texas were not going to be a lot of use up in those particular places. So suddenly, this wacky idea of having skiers and mountaineers come in and train a new group of soldiers started to make a lot of sense, and that’s how this thing got started.

[End McKay Jenkins interview]

America’s mountain-fighting inadequacies might have been alarming to civilians such as Minnie Dole and his friends, but they were a vital threat to the United States Army, one that General Marshall took seriously. Marshall had been studying the country’s readiness for mountain warfare prior to the Soviet invasion of Finland. In its aftermath, he assigned two key members of his team, Lieutenant Colonels Nelson M. Walker and Charles E. Hurdis, to study the topic more thoroughly. When Walker met with Dole in the fall of 1940 to discuss a mountain unit, his support, and that of Hurdis, became key to its formation. As an essay in the 1946 American Alpine Journal War Edition noted, “To these officers great credit is due for their part in organizing the first mountain regiment and in encouraging the War Department to continue to give direct aid to mountain training.”

This is not to say that America’s winter warfare experiences were non-existent before the 1939 invasion. As early as the winter of 1775-76, during the Revolutionary War, American soldiers used skis, snowshoes and sleds to move cannons over the snowy New England hills. And from 1886-1918, US Army troops used skis to patrol yellowstone national park in winter to keep poachers at bay.

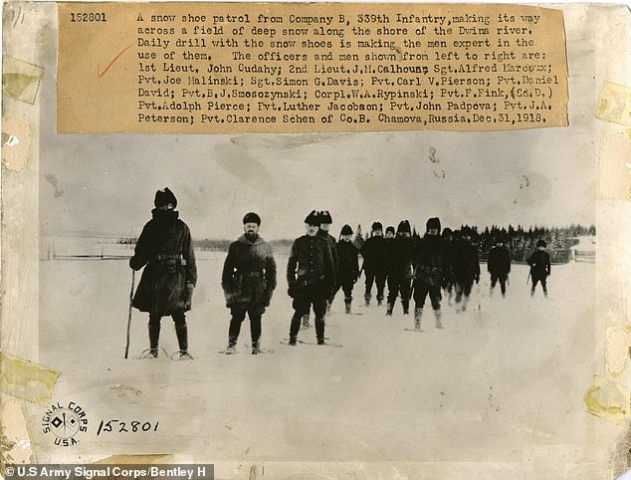

But it wasn’t until the 1918 deployment of US troops to aid the White Russians during the Russian Civil War that a US Army unit received its first real winter warfare training—in what came to be known as the Polar Bear expedition.

In September 1918, in response to requests from the governments of Great Britain and France, President Woodrow Wilson sent a contingent of some 5,000 troops from the 339th Infantry Regiment to fight the Red Army. The unit received nominal winter training in England before continuing to the Archangel / Murmansk area of Northern Russia, where it fought through the bitter cold of the Russian winter using skis, snowshoes and sleds to maneuver through the deep snow.

Upon the Regiment’s return to the US in the summer of 1919, much of its equipment was transferred to Minnesota’s Fort Snelling, one of the small, 19th-century outposts that was being used to guard the country’s northern border with Canada. Many of the few hundred soldiers stationed in Fort Snelling were from America’s northern latitudes; accustomed to harsh conditions, they knew how to make the most of the winter months. For the next twenty years, equipment from the Polar Bear Expedition was used sparingly by these soldiers for training in winter warfare, and more frequently for recreational outings.

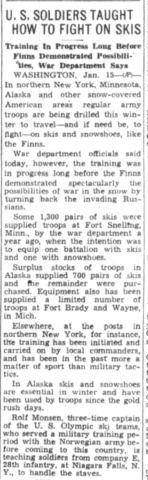

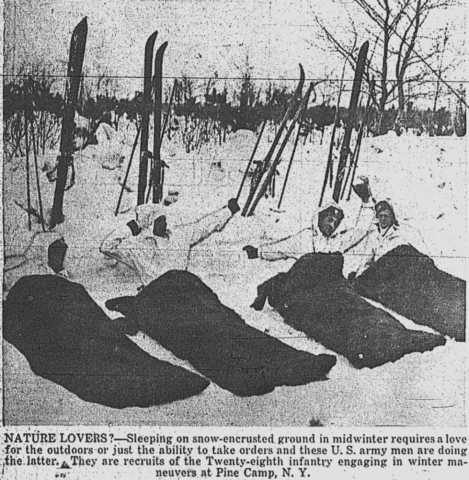

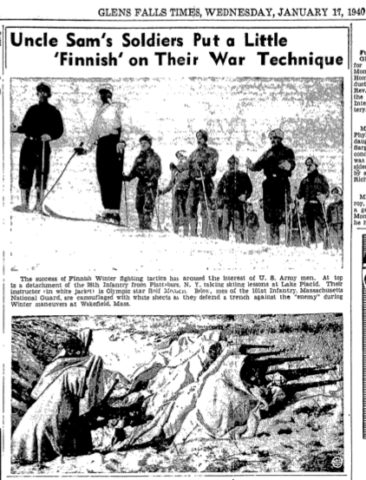

In the fall of 1939, the Army began to plan its first large-scale winter maneuvers, drawing soldiers of the 28th Infantry Regiment from two border outposts, New York State’s Pine Camp and Lake Placid. The Soviet invasion of Finland gave the winter maneuvers a new sense of urgency, especially once the success of the Finns against the heavily mechanized Soviet forces caught the world’s attention.

These maneuvers were not without their hiccups: unfamiliar with the nuances of skiing, for example, organizers purchased skis without realizing that they needed to buy bindings to go with them. But from January through March, 1940, at both Pine Camp and, to a smaller extent, at Lake Placid, New York, some 1,000 soldiers donned white camouflage and practiced their maneuvers on skis, snowshoes and with toboggans—a training the Army declared a notable success, as well as a potential template for future exercises.

Who gave the directive for augmenting America’s cold-weather capabilities with the maneuvers? The most logical suspect is the military’s highest ranking officer, Chief of Staff General Marshall. The army was aware of the need to train soldiers in the art of winter warfare, and General Marshall had a history of big-picture thinking that would prove pivotal to American victory in the war. Not only would he oversee an expansion of the military from the world’s 17th largest army, just behind that of Romania, to the most effective, best-equipped fighting force in history; he would lay the groundwork for the creation of America’s first armored, airborne as well as mountain divisions, none of which existed before the war.

But what sparked General Marshall’s initial consideration of a mountain troops, and when did that inspiration occur?

For the purposes of our story, the most important point about the Pine Camp maneuvers is the date. Planning for them began in the fall of 1939—before the Soviet invasion of Finland and long before Minnie Dole’s 1940 gathering in Vermont.

And this is where we enter a story about the 10th Mountain Division’s formation that history has forgotten—and it’s a story that begins not with skiers, or the army, but with climbers, from the American Alpine Club.

The Hungarian-born geologist, naturalist and explorer Angelo Heilprin had founded The American Alpine Club as an “alpine society” in 1902. Thirty-seven years later, in 1939, it boasted 11 honorary and 242 dues-paying members, including many of the country’s most prominent mountaineers.

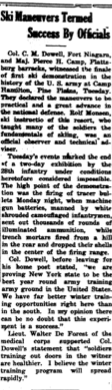

As with the leadership of America’s burgeoning ski community, the AAC’s ranks were populated by affluent members of society. Among them were a group of twenty-something wunderkinds known as the “Harvard Five.” This group, which included H. Adams Carter, Bob Bates, Bradford Washburn, Charlie Houston, and Terry Moore, had helped advance the standards of American mountaineering in the 1930s. Carter and Bates would go on to play important roles in the 10th’s development as well.

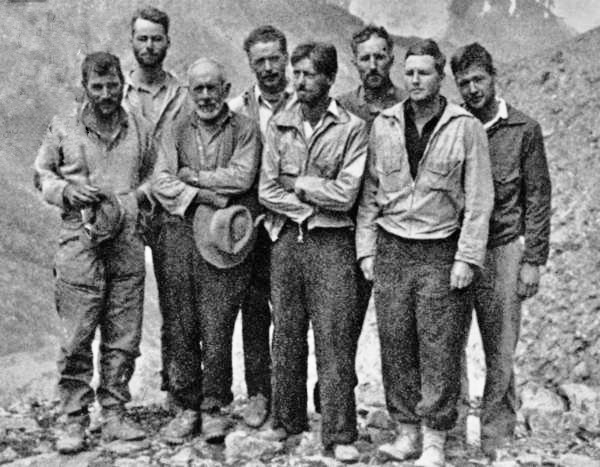

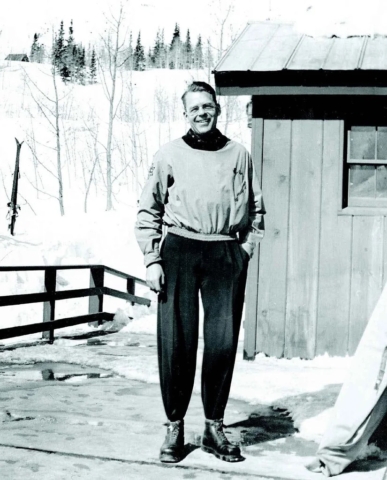

In 1939, Hubert Adams “Ad” Carter was twenty-five years old and already had a number of significant climbs to his credit. A New Englander, he had made his first ascent of Mount Washington at the age of five; fifteen years later, while studying at Harvard, he had made the first ascent of Alaska’s Mt. Crillon with fellow student Bradford Washburn. In 1936, at age 22, “Ad,” as he was known to his friends, had helped plan the British-American Himalayan Expedition to India’s 7816-meter Nanda Devi from his Harvard dorm room. The expedition was successful, and Nanda Devi remained the highest mountain ever climbed until 1950. Ad was also an expert skier, and had competed in the 1937 Alpine World Skiing Championships and the 1938 Panamerican Championships as a member of the United States Ski Team.

A rumpled, deeply amiable man with a profound interest in the human condition, Ad was also a polyglot: when he was fifteen, he’d lived for a year with Switzerland’s most respected guiding family, the Ogis, with whom he’d learned to both climb and speak German like a local. He was also fluent in French, Italian and Spanish, and had learned Balti with his porters on the approach to Nanda Devi.

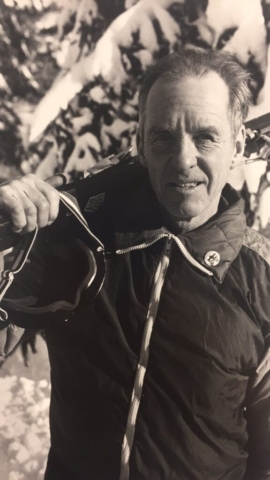

Robert Hicks Bates was three years Carter’s senior, a joyful, intelligent, self-effacing man with a guttural laugh and a twinkle in his eye. Slight, short, and skinny, he’d attended Harvard from 1929 to 1933 as an undergrad and from 1933-1935 as a graduate student, earning his master’s degree at the university. Like Ad, he was a member of the Harvard Mountaineering Club. In 1937 Bates and Bradford Washburn had made the first ascent of the highest unclimbed mountain in North America, the Yukon’s Mount Lucania, a climb that ended with a mapless, 100-mile trek back to civilization through the wilderness. In 1938, on an expedition put together by Charlie Houston, Bates attempted the world’s second-highest mountain, the 8611-meter K2. On that trip, Teton pioneer Paul Petzoldt, who we’ll meet later in this podcast, reached a height of 8100 meters—higher than anyone else had ever climbed.

In the summer of 1939, Bob traveled to Switzerland to join Ad on a climbing trip. Traveling to Europe at the end of the Great Depression to do something as frivolous as climbing is an activity that only a few could enjoy, a topic we’ll tackle in the next episode when we look at the state of outdoor recreation in America before the war. For the purposes of this episode, we’ll simply quote from Bates’ memoir, The Love of Mountains is Best:

“At mountain huts it was not easy to get world news but we did learn from hutkeepers that war was appearing more likely between Germany and Poland. The Germans were getting very aggressive and almost all the Swiss we met were apprehensive. We saw Swiss mountain troops maneuvering and we talked about how the US Army could make good use of mountain troops too.”

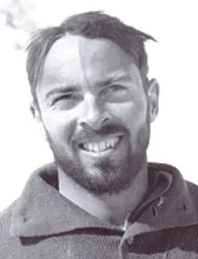

As we learned earlier in this episode, President Roosevelt replaced the isolationist Secretary of War, Henry Woodring, with the interventionist Henry Stimson in June of 1940. What we haven’t yet mentioned was the fact that Stimson was also a climber and a former and future Honorary member of The American Alpine Club, of which both Carter and Bates were members in very good standing. Carter subsequently met with Stimson, conveying their concern.

Maurice Isserman is a climbing historian and Professor of American history at Hamilton College. He has written a history of the 10th Mountain Division entitled, The Winter Army: The World War II odyssey of the 10th Mountain Division, America’s Elite Alpine Warriors.

He has also written a history of Himalayan mountaineering entitled Fallen Giants. In it, he writes, “Carter and Bates lobbied both US secretary of war Henry Stimson, and US army chief of staff George C Marshall on the need for mountain troops.”

I’ve asked Professor Isserman to help us understand how his research led him to Carter and Bates’ lobbying efforts, and how those efforts contributed to the creation of the 10th Mountain Division.

[Maurice Isserman interview]

I’m not a military historian by training; I haven’t written any other military histories. But in writing about the history of mountaineering in general and American mountaineering in particular, I kept running into the 10th Mountain Division. I wrote a book called Fallen Giants—a history of Himalayan mountaineering. And I ran into a number of characters like Bob Bates and Ad Carter associated with the American Alpine Club, who in the 1930s were pioneers and American adventurers in the Himalaya, and they both had connections with the creation of the 10th Mountain Division—and again, writing Continental Divide, my history of American mountaineering, I ran into lots of ways in which climbers coming out of the American Alpine Club, the Sierra Club, and few other places contributed to the creation of the 10th Mountain Division. So I sort of backed into writing this military history about the first American alpine fighting unit.

Well, the standard story, and it’s not untrue, is about a guy named Charles Minot Dole, or Minnie Dole, who was a founder of the National Ski Patrol and an avid and very good amateur skier, along with several friends of his, came up with the idea for the 10th Mountain Division after a long day skiing one day in February 1940—that is, before the United States was a belligerent. But then the Second World War was already about six months old, and they were thinking that eventually the United States was going to get involved in it. And given that potential enemies, like Germany and Italy, had a well-developed tradition of mountain troops, given that their national borders fell on the Alps, the United States should think about doing the same. And the National Ski Patrol was undoubtedly a very important contributor to 10th Mountain Division. But there was another side to that story, and that involved the climbing community, which at the time, in the 1930s, was quite small, centered in the American Alpine Club, in the rock climbing section of the Sierra Club, in some corners of the Appalachian Mountain Club, and a few other climbing groups, a few university groups. And out of that community came some pretty vital contributions to, firstly, the idea of creating mountain troops, but secondly, to figuring out what they were going to need to do the job in terms of gear, in terms of clothing, in terms of technique.

This is late summer of 1939. And the Second World War begins on September 1st, and they’re in Switzerland and Switzerland, of course, another place with a long tradition of mountain troops, and one that managed to remain neutral in the Second World War. But they’re there when the Swiss Army is on maneuvers, and they observe them as they’re doing their own climbing and kind of look at each other thinking, if the war is coming, and if the United States gets involved in this war, we’re going to need some of those ourselves. And the chronology is not entirely clear about when they began to share this idea but sometime in 1939, 1940, they do begin to reach out to influential people, and some of them in the War Department, to bring this idea to the fore—and their efforts are parallel to, and at the same time as, those that Minnie Dole and his friends from the National Ski Patrol and skiing community are making similar suggestions.

John Imbrie, an American paleoceanographer who served with the 10th during its deployment to Italy, begins his chronology of the Division with an entry about an exchange between General Marshall and Louis Johnson– who, as you’ll remember, was the interventionist appointed by President Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary of War to counterbalance Henry Woodring.

The entry reads,

January 6, 1940. Louis Johnson asks Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall what consideration has been given to special clothing, equipment, food, transportation and other essentials necessary to field an effective force under conditions like those of the campaigns in Finland and northern Russia. General Marshall replies that winter warfare was always important to the Alaskan command, and that for several years winter exercises have been conducted by troops at Fort Snelling, Minnesota and elsewhere. He adds that “Winter maneuvers on a larger scale than yet attempted are desirable, but to date money for this purpose has not been available.”

Imbrie’s second entry is marked May 1940. It reads, “The American Alpine Club urges the War Department to introduce mountain warfare training in the U.S. Army.”

The third entry in Imbrie’s chronology is dated July 18, 1940:

Charles Minot Dole, Chairman of the National Ski Patrol Committee writes a letter to President Roosevelt, offering to recruit experienced skiers to help train troops in ski patrol work.

So who planted the seed for cold weather and mountain warfare with General Marshall: The American Alpine Club or Minnie Dole?

If you’re listening to this unabridged version of the episode, you’re a patron of the show, for which I’m deeply grateful. You may well have the answer to this riddle, and if so, I encourage you to reach out and share it so that we may shed yet more light on the 10th’s origin story–for it has evaded my research, as well as that of our advisory board.

And for your consideration, I offer my bias. Not only am I a climber and ski mountaineer; I am a devoted fan of H. Adams Carter and Bob Bates. When Ad passed away in 1996, I took over the editorial duties of The American Alpine Journal, the publication he had transformed, over the course of 36 years, into the premier chronicle of world mountaineering. Bob Bates and his Harvard Five friends, Bradford Washburn and Charlie Houston, took an interest in my tutelage, concerned, no doubt, that I would inadvertently wreck their dear friend’s legacy. Those men were gentlemen of the first order, humble and kind, and they applied their prodigious skills and energies to improving not only my efforts but the world around them however and wherever they could.

When I read in Bates’ memoir that he and Ad had observed the maneuvers of the Swiss mountain troops in the summer of 1939 and talked about how the US Army could make good use of mountain troops of their own, I became convinced that they’d gotten the ball rolling on what would become the 10th Mountain Division months before anyone else. I wanted it to be them. But I cannot substantiate the assertion that it was.

I’ve spent weeks going through the American Alpine Club board minutes in an attempt to verify Imbrie’s May 1940 entry about the AAC without success. I’ve tracked down Henry Stimpson’s correspondences at Yale and reviewed the letters of AAC officials in 1939 and 1940, but similarly found no smoking guns that point to the organization’s role in a lobbying campaign that predated that of Minnie Dole and the National Ski Patrol System. None of our advisory board members are able to pinpoint the exact catalyst for the division, either.

Most significant discoveries are made independently and more or less simultaneously by multiple people. The same could be said for the realization that the US might soon be engaged in cold-weather and mountain warfare—and that unlike the Finnish guerillas, it was woefully unprepared to do so.

In the end, the 10th Mountain Division’s genesis lay not solely with Minnie Dole and the National Ski Patrol System, nor with General Marshall and the US Army, nor with H. Adams Carter, Bob Bates and the American Alpine Club, but in a simultaneous convergence of all three forces advocating for the unprecedented development of America’s very first mountain troops. As the saying goes, you can get a lot done as long as you’re not concerned about who gets the credit. And in the case of the 10th, the credit goes to all three.

And that concludes Episode 1 of Ninety-Pound Rucksack. Thank you for listening . If you liked this episode, make sure you subscribe to the podcast, and please share it, tell a friend about it and give it five stars on your app.

If you want to learn about the podcast’s genesis, check out episode 0 on christianbeckwith.com, and stay tuned for Episode 2, in which we explore the history of mountain troops in Europe before World War II, the state of outdoor recreation in America before the war, and how the rise of the Third Reich caused some of the best German and Austro-Hungarian mountaineers to flee Europe for America, influencing climbing and skiing on this side of the Atlantic and contributing to the fighting skills of America’s first mountain division.

If you have stories about the mountain troops you want to share, reach out and let me know. I’ll share them on my website, christianbeckwith.com, and include the best of them in the newsletter and in interviews on the podcast. Sign up for the newsletter for info on upcoming episodes, and if you’re really into the story of the 10th Mountain Division, please consider becoming a patron. Patrons get unabridged episodes as well as behind-the scenes content available only to them.

Special thanks go out to our advisory board members, McKay Jenkins, Chris Juergens, PhD, Jeff Leich, David Little, Sepp Scanlin, Keli Schmid, and Doug Schmidt, for their help with this podcast, as well as Professors David Murphy and Maurice Isserman for their contributions, and props go out to Roma Deschenko for his help in putting this episode together.

Until next time, thanks for joining, and I hope you get outside and do something wild today. Remember, climbing and ski mountaineering are dangerous—but without risk, there is no adventure. Have fun, stay safe, and stay in touch.

Mentioned resources

- David Murphy: The Finnish-Soviet Winter War 1939–40: Stalin’s Hollow Victory

- McKay Jenkins: The Last Ridge: The Epic Story of the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division and the Assault on Hitler’s Europe

- Maurice Isserman: The Winter Army: The World War II Odyssey of the 10th Mountain Division, America’s Elite Alpine Warriors

![Henry Lewis Stimson. As Secretary of War under President Roosevelt, Stimson was pivotal to the formation of the 10th Mountain Division. A climber and avid outdoorsman, Stimson had become a member of The American Alpine Club in 1913. In December 1941, The AAC elected him as an Honorary Member, noting “[Y]our immediate interest and endorsement of the suggestion that the Army should organize troops specially trained for mountain warfare… [has] made it fitting that you should again be associated with the Club.” Henry Lewis Stimson. As Secretary of War under President Roosevelt, Stimson was pivotal to the formation of the 10th Mountain Division. A climber and avid outdoorsman, Stimson had become a member of The American Alpine Club in 1913. In December 1941, The AAC elected him as an Honorary Member, noting “[Y]our immediate interest and endorsement of the suggestion that the Army should organize troops specially trained for mountain warfare… [has] made it fitting that you should again be associated with the Club.”](https://christianbeckwith.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/220px-Henry_Stimson_Harris__Ewing_bw_photo_portrait_1929-640x480.jpeg)