Featuring all-original research, Part 4 of our Camp Hale series uncovers how David Brower helped revolutionize American climbing from within the ranks of the (future) 10th Mountain Division.

At Camp Hale, through his authorship of the Rock Climbing chapter in the Proposed Manual for Military Mountaineering, Brower introduced innovations such as dynamic belays, solid anchors, standardized climbing classifications, and communication systems to the American GI—techniques that soldiers would later carry into civilian life, helping to democratize climbing and lay the groundwork for the postwar boom that followed.

The episode also explores the extraordinary young recruits who filled the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment and traces the parallel rise of the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop and the Mountain Training Group. Never before had such a concentration of mountaineering talent been assembled in one place, united by a single purpose: to teach America’s first mountain soldiers how to climb, ski, and fight in alpine terrain.

Working together in the thin air of Colorado’s Pando Valley—testing techniques, trading insights, and blending regional climbing traditions into a unified system—they forged the modern foundations of American mountaineering.

Highlights include:

• David Brower’s Rock Climbing chapter and its influence on military and civilian climbing

• The influx of the remarkable new soldiers of the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment

• The evolution of the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop and Mountain Training Group

• How the Camp Hale experiment helped shape postwar American outdoor culture

Resources & Bonus Content: christianbeckwith.com

Sponsors:

- CiloGear: Premium alpine backpacks – cilogear.com (Code: rucksack)

- DPS Skis: Designing the world’s most advanced skis – dpsskis.com

- Snake River Brewing: Wyoming’s oldest and America’s most award-winning small craft brewery – snakeriverbrewing.com

Support Ninety-Pound Rucksack on Patreon for early access, bonus interviews, and illustrated transcripts.

Special thanks to our newest patrons: Jerry Laverty, Kenneth Brooks, Carter Hatton, Mark Wharton, Eric Corbett, Nairb Lenz, Sydney Palmer, Dan Burgette, Dave Rhodes, Andrew Wilhelm, Neil Gallensky, Paul Kuenn, Chad Horne and Justin Colquhoun.

Camp Hale, Part 4: Episode 14, Unabridged

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and our examination of the mountain troops’ high-altitude encampment in the Pando Valley continues today as the troops begin the warm-weather phase of their alpine training amidst the 14,000-foot peaks of the Colorado Rockies.

We’re now three years, 130,000 downloads and–thank you very much– 300-plus five star reviews into our sprawling story, and to be honest, I’m beginning to wonder if it will take longer to finish than it took the Army to actually build the Division and send it off to war. Were it not for the support of our advisory board and our partners—the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the 10th Mountain Division Descendants, and the 10th Mountain Alpine Club—this journey would be a much more difficult affair.

It’s also made easier by the support of our beloved community of patrons. As you might imagine, the research behind this and every episode can become all consuming, and it wouldn’t be possible without their support. Each month, they contribute a small amount of money to the cause. In return, I publish extended interviews and exclusive content just for them. They really are the heart of our Rucksack community, and if you’d like to join them, I invite you to go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button on our homepage. Subscribing to the story in this way makes it possible for me to continue telling it, so thank you, because your support benefits every single listener who tunes in.

I’d be remiss without thanking our sponsors as well.

This summer, I had the chance to take my CiloGear Worksack on a two-day ramble in the Tetons. Our plan was to climb Mount Owen’s Serendipity Arete, continue up the Grand’s North Ridge and finish with the North Face, a magnificent tour I’d long dreamed of doing. Because I’m not as nimble as I once was, we planned to bivy along the way, which meant sleeping bags and pads and extra food, which—even with today’s new-fangled light weight equipment—meant heavier packs. After thwacking through the shrubbery into the high reaches of Valhalla Canyon, it took seven and a half hours just to get to the base of the route, and another seven to reach the summit. We got lost on the first pitch, thrutched our way up pitches three and five and nine, ran out of water with hours to go, and didn’t top out until sunset.

The one thing that didn’t feel hard that day was my pack. Even with all the extra weight, it clung to my back like a baby monkey, never impeding my leads or my follows. When we finally made it to our bivouac, my partner tore his nozzle off his air mattress with the first blow—so I gently pulled the built in sleeping pad from my CiloGear pack, handed it to him, popped a xanax and fell into a deep dark slumber.

Our adventure the next day did not include the Grand, and we were still plenty pooped by the time we made it back to our vehicle, but I can say this: If you want one amazing alpine backpack that will carry all your gear comfortably and last you for the rest of your life, I can recommend a Cilogear pack without reservations. They’re lightweight, bombproof, as close to perfect as you’re going to find, and made right here in the good ol’ US of A. If you purchase one at cilogear.com—that’s c-i-l-o gear.com—and use the code rucksack, you’ll get 5% off your purchase and they’ll match it with a donation to the 10th Mountain Alpine Club.

And thanks, no doubt, to all the wisdom I’ve been accumulating with each new birthday, my beers from Snake River Brewing were waiting when we staggered back to our car. Even better, my partner doesn’t drink, so I got to enjoy my ice-cold Earned It IPA without having to fend off another beer lover. Snake River Brewing has been making their beers in the shadow of the Tetons for more than 30 years, and somehow they’ve managed to inject the spirit of the mountains into every brew. Whether the finish of another great day in the mountains finds you thirsting for the full-flavored hops of a Paco’s IPA or the crisp, firmly bitter finish of a Snake River Pale Ale or the malt-forward, slightly sweet profile of a Jenny Lake Lager, they’ve got you covered. You can find their beers throughout the west, and if you’re in Jackson, stop by the brewpub to grab some of their delicious grub and tasty brews, all from Wyoming’s oldest and America’s most award-winning small craft brewery. Do yourself a favor and go to snakeriverbrewing.com to learn more.

If there’s one thing I like more than climbing the Tetons in the summer, it’s skiing them in winter—and for that, too, I expect the best of my gear. And when it comes to skis, I don’t think you can do much better than DPS.

They say you date your skis but marry your boots. I’m more of a polygamist: I want all three of us to be one big happy family. And for the past couple of years, two-thirds of the relationship has been great: my boots are awesome. My skis, on the other hand, a very carefully researched pair of 104s, felt like being married to a sensible, practical, predictable roommate. I liked them, and I knew I could count on them to get me from point A to point B—but on some deeper level of my consciousness, I knew a critical part of the affair was missing. They had zero sex appeal.

So when, toward the end of last winter, I started skiing a pair of DPS Pagoda Tour 100s, va-va-va voom: I realized instantly what I’d been missing. With every turn, they popped me out of the snow with that toe-curling passion I’d been yearning for, and the more I skied them, the more I found myself falling deeply, hopelessly, irrationally in love. By the time we got back to my truck and I gently lowered them into the bed, I found myself wearing that tell-tale grin that gets us busted by our friends.

If you want to put that knowing glow back into your cheeks, skin on over to dps.com and have a look. All of their skis are made in their state of the art US factory, with premium hand-selected materials that will last a lifetime. From pow-surfing to piste carving to big mountain riding to backcountry touring, they offer a lineup guaranteed to put the bounce back into your step. Riding a pair of DPS skis is the quickest way to skiing ecstasy. It’s so outrageously fun it almost feels like cheating—but hey, skiing, like life, is too short for platonic relationships.

And now, let’s catch up with our hero, John McCown, who is about to learn the art of the dynamic belay from one of the best in the business.

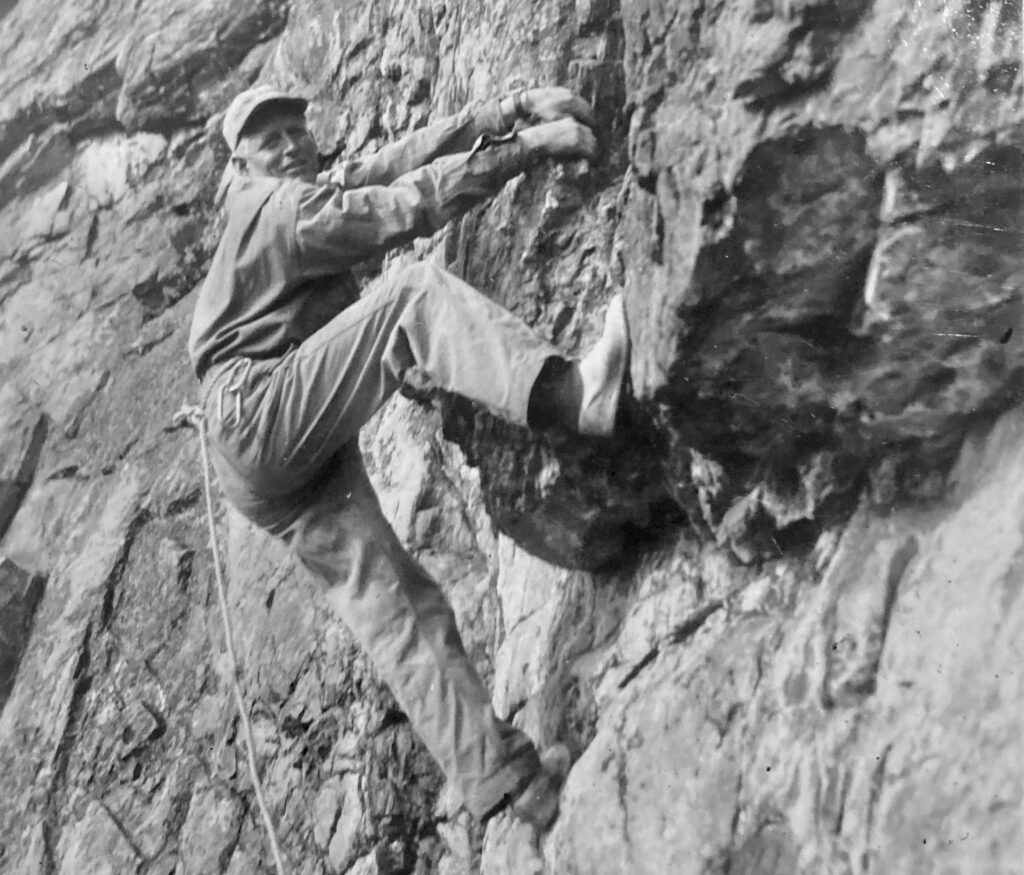

“The trick,” said Private 1st Class David Brower, “is to let the rope out as he falls.” He was six-foot-two and a bag of bones, his lean frame and high, skinny shoulders barely filling out his reversible parka. “That’ll keep it from breaking.” Then he added, “Sir.”

It was late winter, 1943, and the thirty-one year old Brower was standing half a dozen feet back from the edge of a cliff, holding a rope low around his hips in the palms of his hands. Just ahead of him sat 2nd Lieutenant John McCown. John had tied a bowline on a coil around his waist; Brower’s rope was tied to the knot, which John had positioned at his back.

Private Artur Argiewicz, a skinny, bespectacled nineteen-year-old, perched on a ledge just above them. John held a second rope low on his hips. Its sharp end looped up to Argiewicz.

“Are you sure about this?” John asked.

“Yes, sir,” Brower said, his voice bobbing with delight. He was obviously enjoying himself, as were the small group of men who had gathered to watch.

Below them lay Camp Hale, its streets checkerboarding the width and length of the Pando Valley. Piles of snow dotted the intersections and huddled in the buildings’ northern lees. Across the valley, snow peeked from between the pine trees covering the hillsides .

After two months of brutal cold, the sun felt luxuriously warm, but John was too nervous to notice. He was afraid he was about to be the death of Private Argiewicz.

“The magic is in the slip,” Brower continued. “When Arte comes onto the rope, let it slide through your hands before you tighten up. You want to decrease the speed gradually, not with a jerk. Absorb his fall with your hands and body.”

“Don’t worry, sir,” said Argiewicz, a toothy grin breaking over his long, narrow face. He looked back at John over his shoulder. “We’ve done this a hundred times at Indian Rock. Hardly lost anyone.”

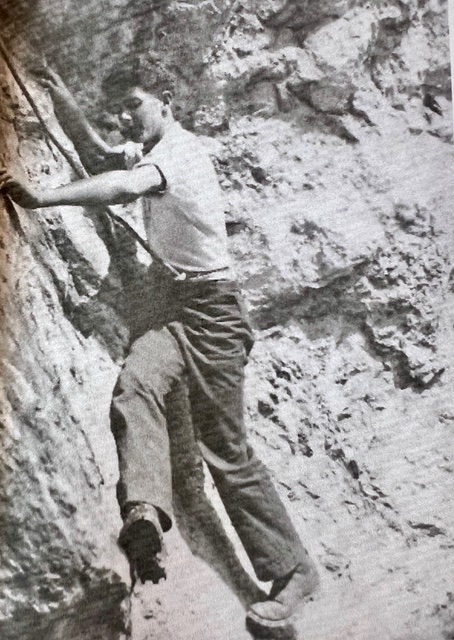

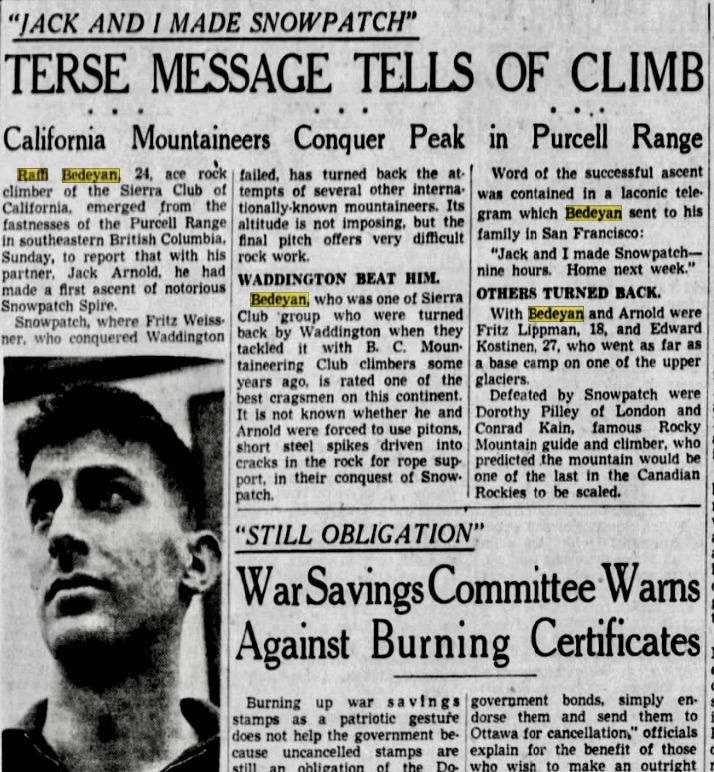

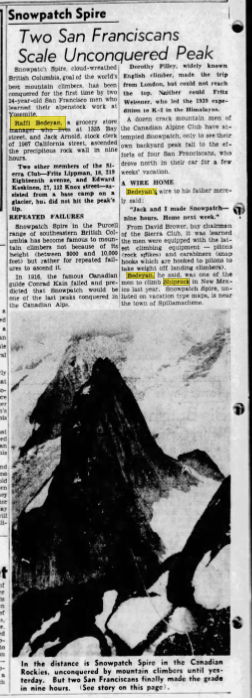

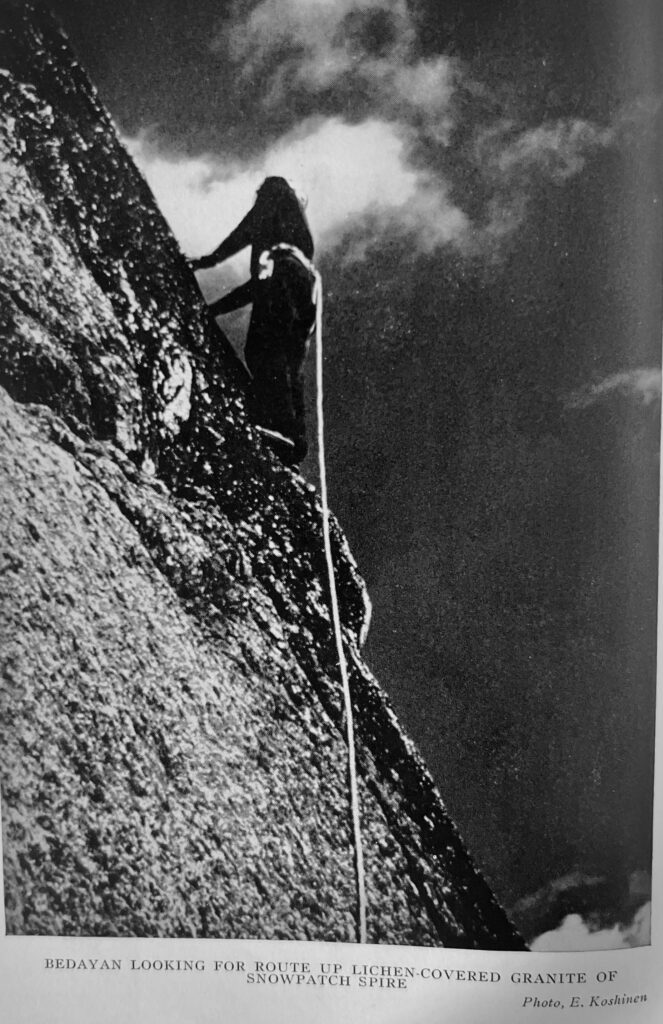

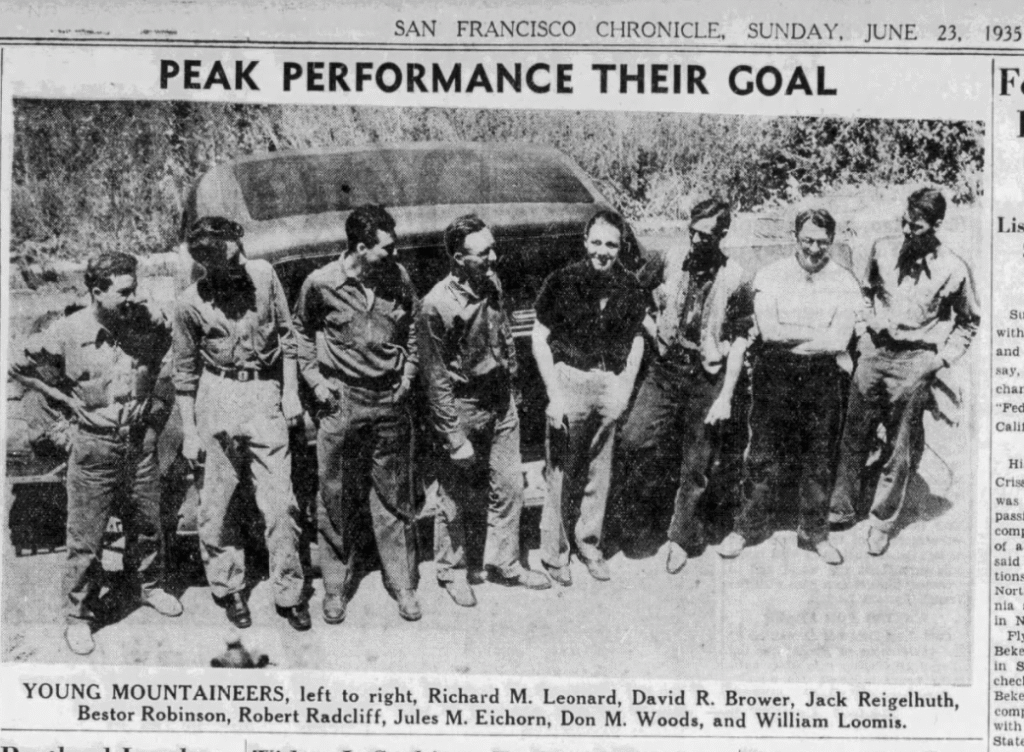

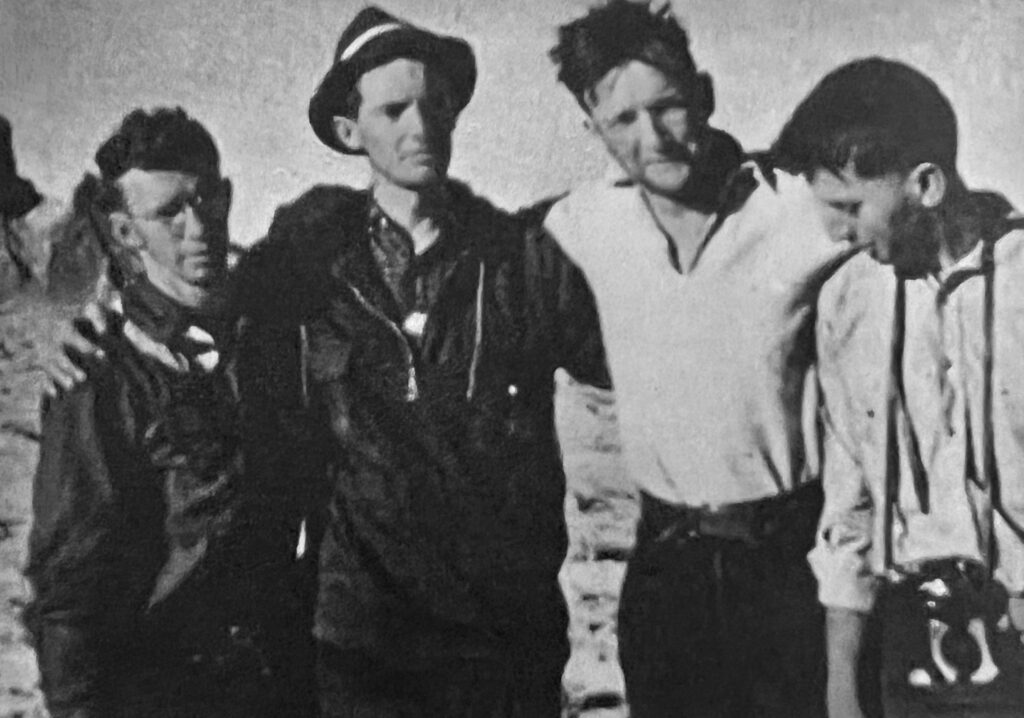

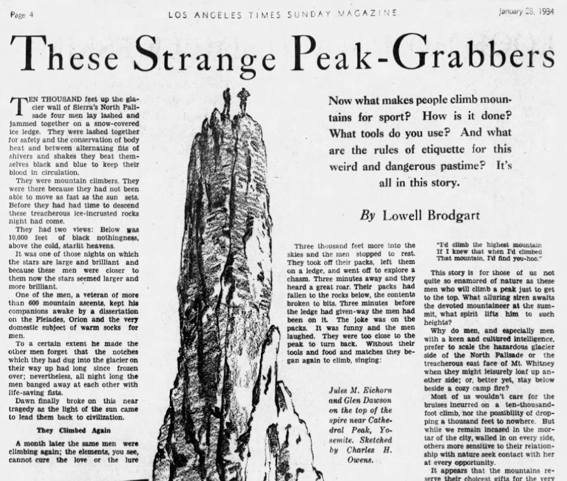

An awkward chuckle played out among the onlookers. Some of them, like privates Glen Dawson and Raffi Bedayan, had been Brower and Argiewicz’s fellow members of the Rock Climbing Section of the Sierra Club. They’d practiced falling and belaying together on the boulders around Berkeley, then taken their schooling to the fabled walls of Yosemite Valley, with historic results. Others, like Captain Johnny Woodward and 1st Lieutenant Ed Link, were primarily skiers who nonetheless would soon have to figure out how to teach neophytes to climb.

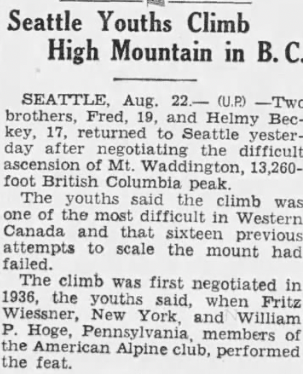

As word had gotten out about the training session, other climbers—nineteen-year-old private Fred Beckey, fresh off the second ascent of Mt. Waddington, one of North America’s most audacious peaks; private Joe Stettner, a German-American alpinist twice Beckey’s age; Swiss mountaineer, world downhill ski champ and Dartmouth ski coach Walter Prager, now one of the most accomplished mountain troopers in camp—had finagled their way into the training as well.

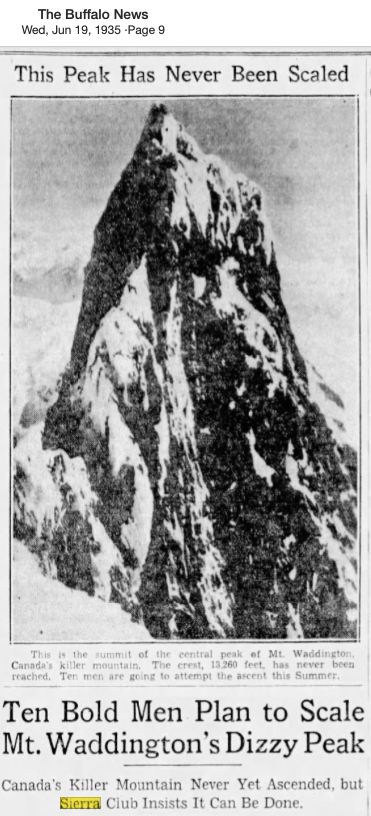

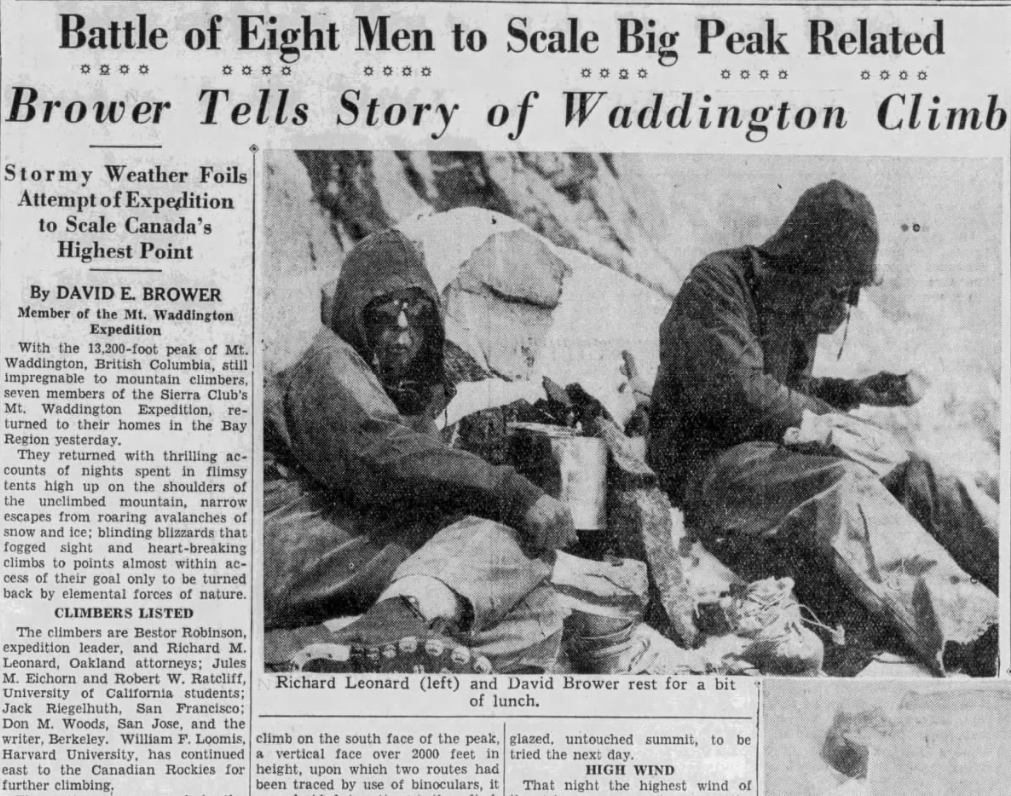

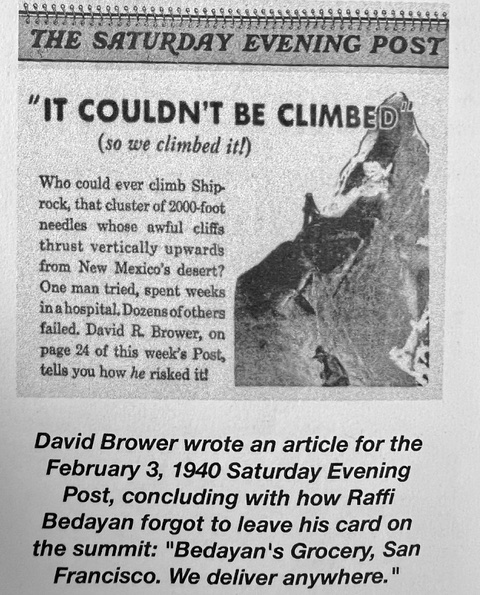

Sun, Aug 23, 1942. The climb garnered far less attention than David Brower’s attempt on the mountain’s first ascent with a Sierra Club group in 1935.

There was an excitement to the gathering that even the ambient air temperature couldn’t chill. Part of it had to do with the Sierra Club climbers, and the chance to witness their famous techniques first hand; but there was a business side to it too. Everyone atop the cliff that afternoon had a job to do, and they were running out of time.

“I always thought the leader wasn’t supposed to fall,” John muttered. He wiggled his hips on the rock as if trying to find purchase with his sit bones. He could feel the lay of the rope through his fatigues as he shifted it back and forth between his leather-gloved hands.

“If you don’t know what you can hold, you’re right,” said Brower. “But that’s the beauty of practicing: it lets you find the edge. The belay changes everything. You’ll catch him. Don’t worry. Remember, you weigh twice as much as Arte!”

Brower’s optimism was infectious, John had to give him that. He felt a mantra rising in his chest: he could do this. It braided around his nervousness into something like resolve.

“Don’t think of it as stopping the fall. Think of it as slowing. Let the rope slide over your hips as you lean back so you can absorb the shock gradually.”

“You’ve going to love this, sir,” Argiewicz chimed in, pushing his wire-rimmed glasses up the bridge of his nose. “It’ll open up routes you’d never thought you could climb.” He paused for a moment, then added, “No officer has ever been court martialed for killing someone with a bad belay—have they, sir?”

John could hear Dawson and Bedayan smothering laughter behind him, but it barely registered . He was far too focused on Argiewicz and his imminent leap.

“Fall!” shouted Brower.

Argiewicz jumped from the cliff and began plummeting downward. As John braced for the impact, adrenaline coursed through his body. It was the antithesis of everything he’d ever known as a climber: the leader wasn’t supposed to fall, and yet here was the “leader,” airborne, with the only thing between him and a bloody stain on the talus the rope around John’s hips.

“Let it out!” Brower shouted. Every instinct in John’s body screamed at him to clamp down on the rope as hard as he could, but he let it run between his gloves instead.

The force of Argiewicz’s fall yanked him forward. He let five feet of rope out, then ten, the rope zipping across the back of his jacket as he began to squeeze. The knuckles inside his gloves turned white as he slowed it to a stop.

“Gee wiz, wasn’t that something?” Brower exclaimed. He was genuinely delighted. Spontaneous applause broke out among the onlookers.

“I’m not dead!” Argiewicz’s voice rose from below.

“He’s not dead!” Dawson exclaimed, for the benefit of the group.

“You Californians,” John laughed. Despite the cool temps, he could feel a bead of sweat rolling out from beneath his helmet and into an eyebrow. “No wonder you got up those walls in Yosemite—you’re crazy!”

“It’s not crazy if you know it works,” Brower giggled. The sound was endearing; it reminded John of a braying donkey. He also made a mental note: it took a natural leader to get someone to believe in something so obviously irrational.

“That’s what all the practice taught us,” Brower continued. “The dynamic belay works. We never knew what we could pull off until we spent all that time taking falls.”

John continued lowering Argiewicz to the talus, playing the rope out around his hips.

Brower walked closer to John, lessening the space between them. “We’ll take you to Yosemite once this war’s over,” he said, quietly. “You’ll love it–you’ll fit right in.”

“I sure would like that,” John said. He was surprised to realize how tense he’d been. Now, as he relaxed his shoulders, relief washed over him, along with a heightened sense of awareness. The light illuminating the pine boughs was so clear he could see the individual needles. “Let’s debrief tonight—I want to go over the rest of your program.” He lowered his voice so that only Brower could hear. “I want to hear about your attempt on Waddington, too.”

“We should invite Beckey,” Brower agreed. He looked over at Private Beckey, whose helmet was shadowing his young face from the afternoon sun. “I still can’t believe he got up that thing.”

“Dawson!” shouted Woodward. “You’re next! Tie into the rope. Private Beckey—time to show us what you’ve got!”

Did David Brower really provide an impromptu practice session on the cliffs around Camp Hale for John McCown and his fellow instructors on a warm-ish afternoon in the winter of 1943? We have no way of knowing for sure; there is no record of such an event, and only by piecing together the small bits of information available to us can we imagine a scenario wherein such a session took place.

What we do know, however, is this.

By the end of January, efforts to expand the test force into a full division were well underway. All three battalions of the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment had arrived, complete with more than a little veteran swagger. Thanks to John Jay’s Herculean publicity efforts, the ranks of the newly activated 1st Battalion of the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment had begun to fill up as well—and freshly minted officers like John McCown were helping stand it on its feet, their task made notably easier by the National Ski Patrol System’s rigorous vetting process.

Camp Hale’s newspaper, The Ski-Zette, had launched in December as a bi-monthly. On March 9, it graduated to a weekly, with columns written by representatives from the camp’s various units. A quick glance at the regiment’s column, “At Ease with the 86th,” reveals a roster of some of the most accomplished overachievers the Army had ever known—thanks, in no small part, to the NSPS’s recruitment.

As the 86th’s Genter Dahl wrote on April 21, 1943, his new company’s digs “had a tendency to look like a college dormitory rather than an army barracks during the first few weeks of … basic training…. This was almost to be expected, for the greater part of the company had at some time or another attended college. Harvard is represented by Kevin Andrews; Princeton is represented by George Cook and Ernest Wiel; Yale boasts Tom Cole and Larry Broderick, and Richard Martinez comes from the University of Maine. …”

Also present was Lieutenant William Bowerman, who, Dahl noted, had instituted intercompany entertainment on Thursday nights. Though Dahl didn’t mention Bowerman’s alma mater—the University of Oregon—his name might still ring a bell. After the war, he founded a little company called Nike.

At this point in the Army’s remarkable, civilian-soldier revolution, college education remained a relative rarity. Of the Old Army Regulars who made up much of the officer class, around 4% had attended college. 11% of those who’d arrived via the draft, meanwhile, had some form of college education. Those percentages, though, were dwarfed by the degree-wielding men flowing into the 86th.

The new recruits were athletically gifted as well. Luminaries included Richard Dixon, who’d been a member of Northwestern University’s basketball, football and baseball teams; Dick McClintic, the Ohio, Michigan, California, and Rocky Mountain welterweight boxing champion; and Robert P. Major, Jr., who’d been a tennis, track and field, basketball and football star at UCLA.

Pvt. Clarence Knapp had been a rookie with the Chicago Cubs. Sgt. Anthony Bianca of E Company had played pro football for two years with the Hartford Blues. Dartmouth skier John Litchfield had been a member of both the first U.S. and 1940 Olympic ski teams.

If you’re beginning to suspect recruits like these were not your run-of-the mill GIs, you’re right. While less than 40% of the men in the Army’s other units qualified as officer material, 64% of the men in the 86th could lay claim to that distinction. 33% of the men elsewhere in the Army tested below its medium intelligence level; 6% of the men flowing into the 86th had a similar dubious distinction. Though only a fifth of the men funnelling into Camp Hale had arrived via the National Ski Patrol System’s recruitment system, it was a hell of a 20%.

“All these men were excellent mountain troop material,” John Jay wrote in his history of the mountain troops. “Not only were [they] skilled in the ways of skiing and the mountains, which in itself cut down the training time by one-half, but they were smart, keen, [and] enthusiastic [about] a job they had picked out for themselves.”

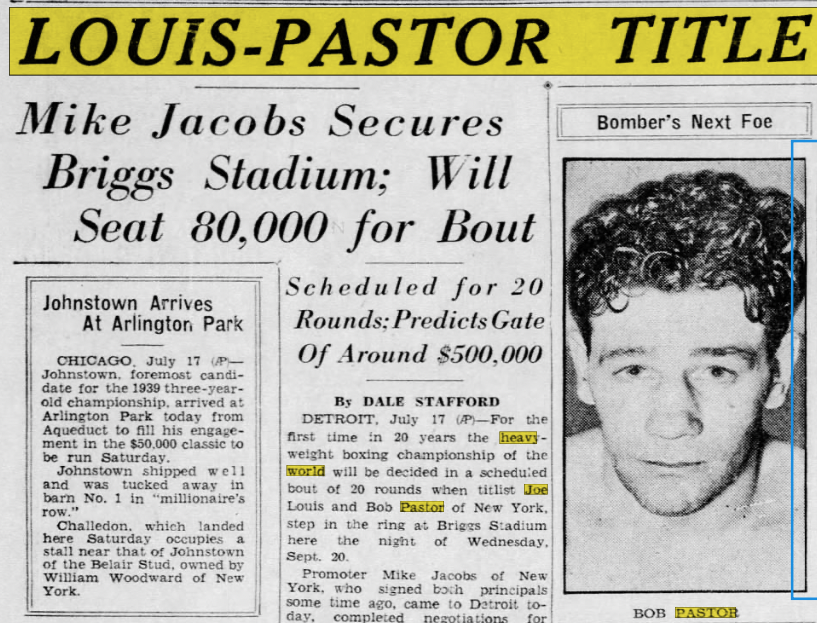

Perhaps the regiment’s most famous addition–or at least one in the running for the greatest number of column inches in the Ski Zette–was Pvt. Robert Pastor, who, in 1939, had gone toe-to-toe with Joe Lewis in a 20-round bout for the title of world heavyweight boxing champion. Though the 29-year-old celebrity pugilist had a wife and two kids back home in Saratoga and thus could have skipped out on the military altogether, he’d enlisted because he felt that “it was his duty as an American citizen.” He’d incorporated cross-country skiing into his training for the title, and now he wanted to put it to work with the mountain troops.

Soldiers like Pastor gave the 86th something to crow about. As “[h]and-picked men from the ranks of the National Ski [Patrol System] began to flow into [the new regiment]—high school stars, college men, all young men of far-above-average abilities,” Jay noted, “an esprit de corps [quickly] grew up in the 86th, much as had grown the year before in the 87th, from which the cadres had been drawn….”

As a result, “The 86th rapidly assumed the reputation of a ‘crack outfit.’”

That reputation almost certainly rankled the veterans of the 87th, particularly as more and more of them were, like John, reassigned to the 86th to bring the youngsters up to speed. They too had college graduates and nationally renowned athletes and skiing superstars of their own to brag about, and they did so in the pages of their column, Views and Vistas of the 87th.

L Company’s Pvt. Jacob Nunnemacher, for example, had captained Dartmouth’s 1942 Ski Team. Warrant Officer Junior Grade Merril Goldberg with K Company had been captain of the ski team at Lafayette. Private First Class Wendell Broomhall over in A Company had been both a North American and International Cross Country ski champ.

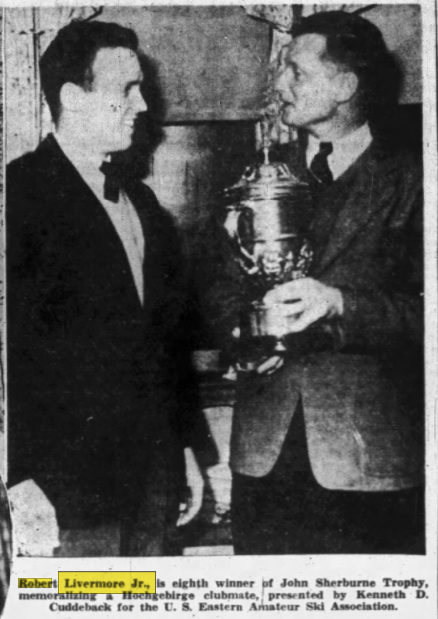

Lt. Robert Livermore, Jr., had founded America’s first downhill ski club while attending Harvard, then gone on to represent the US as a member of the 1936 Olympic ski team. You might also recognize his name from Episode 1, for he’d helped organize the National Ski Patrol System alongside Minnie Dole, Roland Palmedo and Alex Bright in 1938. He’d also been part of the February 1940 meeting with Dole, Bright and Roger Langley generally credited with sparking the creation of the mountain troops in the first place.

It wasn’t just American notables filling the ranks, either. Fueled by Hitler’s occupation of their homelands, European experts were showing up in Camp Hale as well.

Joining the German-American climbing whiz Joe Stettner and the Swiss mountaineers Walter Prager and Peter Gabriel were men like the German-born S/Sgt. Peter Pringsheim, a physics instructor with a Ph. D. from the University of Freiburg whose side hustles included mountain guide, ski instructor, and Olympic ski coach. The 87th’s Anton Bergson, who held a Ph. D. as well as a law degree, had been a member of the Austrian mountain troops. L Company’s Pfc. Dino Sonnino, who’d received his Doctorate in Economics from the University of Rome, had served in the Italian Mountain Troops as a lieutenant.

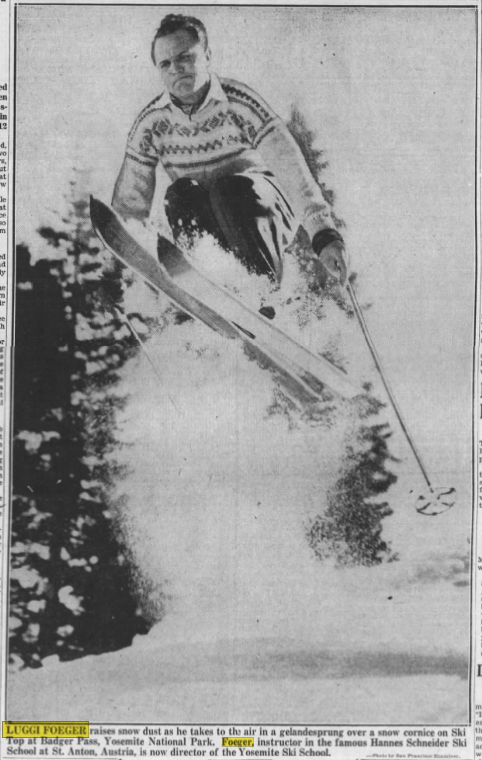

A number of Hannes Schneiders’ Austrian acolytes were joining the ranks as well. Tyrolean mountaineer Luggi Foeger had been given 24 hours to leave the country by the same Nazis who’d tossed his mentor in jail for refusing to bend the knee.

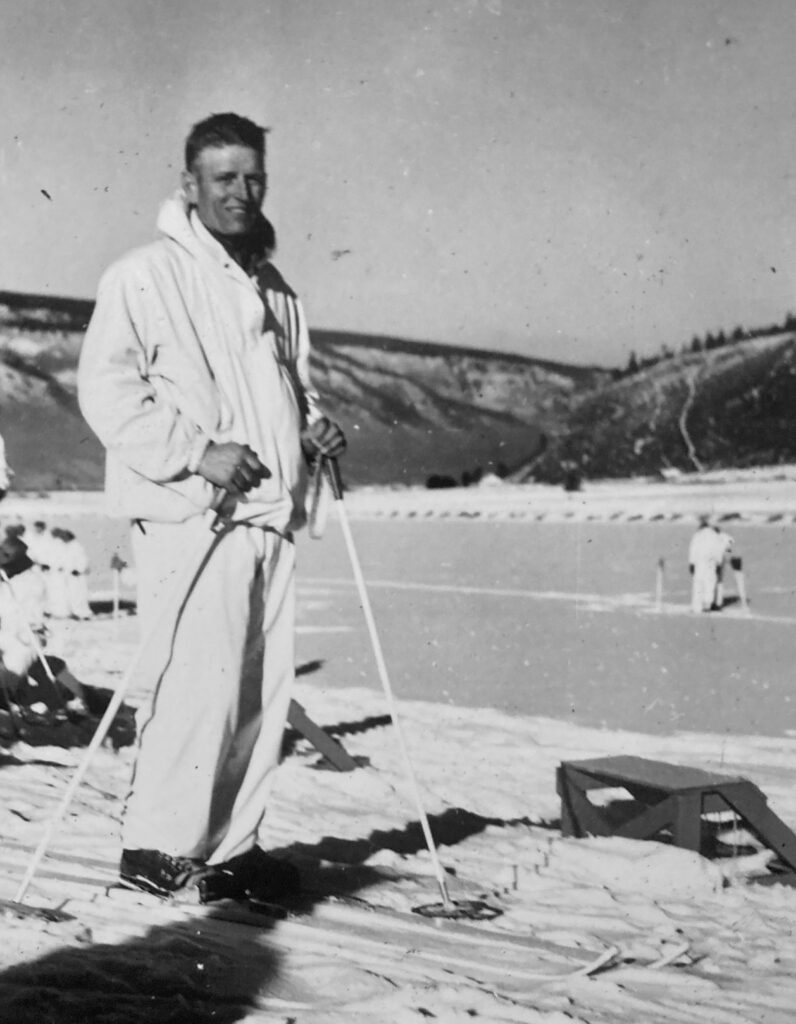

Brought state-side by the American skiers who eventually secured Schneider’s release, Foeger had become a moving force in ski programs across the continent, instructed at one of the largest ski clubs in Chile and directed Yosemite’s Badger Pass Ski School. Now he was Pvt Luggi Foeger, serving alongside Austria’s 1938 Junior National Ski Champion Toni Matt, part of the small army of Austrian proselytizers Schneider had sent to the US to help spread the Arlberg gospel. Matt had won the U.S. Downhill Championships in 1939 and 1941; more famously, he’d tucked the Headwall, a 1,000-foot, 50-degree drop on Mount Washington’s Tuckermans Ravine, in a single long swoop during the third American Inferno. By the time he crossed the finish line, he’d reached speeds of ninety miles per hour, halved the course record, left the 1,600 spectators who’d hiked two hours to witness the spectacle dumbstruck and earned a place in the American ski pantheon in the process.

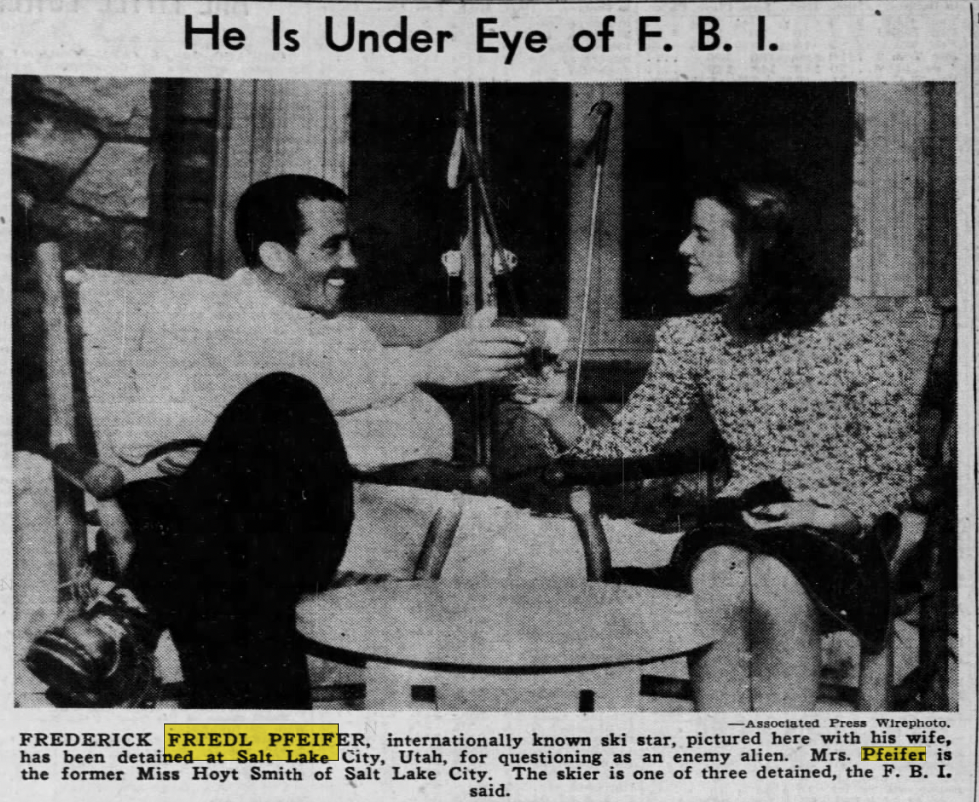

Schneider’s son Herbert walked through the gates on June 12. Hot on his heels was none other than Friedl Pfeifer, Schneider’s first assistant at St. Anton am Arlberg, winner of most of the major European races and championships, former head of the Sun Valley Ski School, and two-time winner of the U.S. National Slalom title. His arrival sent Pfc. Mason Tap Goodenough—formerly the ski editor of the Boston American—into paroxysms of excitement in the Ski-Zette.

“He has scaled the sheer sides of every precipitous peak in Europe,” Goodenough wrote in the July 16 edition, “and was commissioned to give all the certification exams to the guides of Austria, this denoting that he had been recognized as a master of mountaineering…. Those who have seen this hickory hopper perform agree that here is poetry in motion, as he swoops like a snow bird through the heavenly tapioca, sending up the powder in swirling geysers.”

In addition to his skiing prowess, Pfeifer had been an alpine guide and was a rock climber par excellence. “I volunteered for the Mountain Infantry,” Pfeifer told Goodenough, “because I hope to be of aid in teaching skiing and rock climbing… with enthusiasm. After this work is carried out, it is my desire to go into combat, to fight until we have achieved victory!”

Pfeifer and his European counterparts had grown up amidst a mountaineering culture far richer than anything America had ever known, and their arrival in camp gave the mountain troops a much-needed injection of mountaineering expertise. As great as all this talent might have been, though, there remained one mission-critical skillset in very short supply. “At one point, in the spring of 1943,” Jay observed, “there were not more than twenty men in the entire complement at Hale who could qualify as [climbing] instructors.”

Even General Leslie McNair, commander of Army Ground Forces, understood this was a problem. “[Experienced mountaineers] trickle in so slowly,” he wrote to incoming American Alpine Club president John Case in July 1943, “that the training progress of units is retarded seriously.”

There was a reason for the shortage, of course. Apart from a handful of outliers like John McCown and David Brower, American climbers were a statistical anomaly. “[T]he number of skilled mountaineers in the United States,” Jay observed, “could be counted in two figures.” Having counted them myself, I’d say Jay was off by a zero—but that still left Brigadier General Onslow Rofle, the camp’s commanding officer, with a dilemma. He needed climbers to shift into the summertime phase of training, but there weren’t enough of them to go around. If he had any hope of developing an effective force, he’d need to improvise.

The solution? Wrangle the two dozen or so resident experts into a team that could teach the rest.

“This tiny nucleus,” Jay wrote, would become the instructor cadre “of another slightly larger group who in turn could be expanded as a true instruction staff, under the direct supervision of the few experts.”

The idea of an instructional nucleus wasn’t new. John Woodward had championed the concept in the fall of 1942, when he’d chosen 100 instructors from the 87th to write ski and climbing manuals, develop training schedules and identify training locations for the troops at Camp Hale. As we noted in our last episode, he’d roped David Brower into his plans almost as soon as he arrived at Camp Carson, enlisting him to help develop a primer on mountain warfare. He’d swept John McCown into them too.

By mid-winter, the vision for the instructional cadre had evolved. Not only would its mountaineers bring their expertise to bear on training within the Pando Valley; they would be deployed outside it on an as-needed basis as well.

Which brings us to… no, not the climbers atop the cliff at the start of this episode. That would be too easy. Rather, it brings us to the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop.

Numerous aspects of the mountain troops are confusing, opaque or require an advanced degree in military studies to understand. Few of them, though, have a backstory as convoluted as that of the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop—or proved more pivotal to the 10th’s training, and to American climbing and skiing after the war.

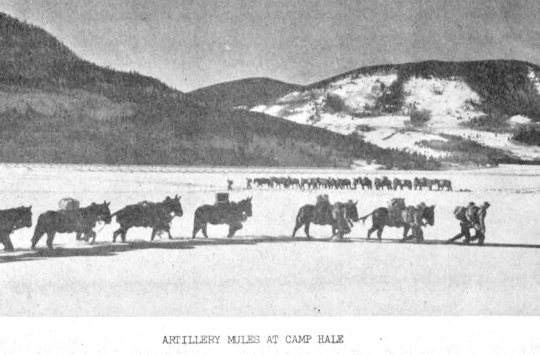

You’ll recall that the Cavalry Troop had been formed at Fort Meade, South Dakota, on September 7, 1942. By the start of World War II, Fort Meade was one of the Army’s last remaining cavalry posts, and the displacement of horses by motor vehicles, heavy artillery, aircraft, rapid fire weapons and other mechanized forces was nearly complete. Even a World War I cavalryman like Rolfe, who’d mandated equine training at Ft. Lewis for John McCown and his fellow soldiers, had soured on their utility. In June of 1942, Rolfe had sent a platoon of the 87th on a two-week horseback trip into Washington’s Olympic Mountains. The trip, documented in the November 9, 1942 edition of Life Magazine—you know, the one with Walter Prager on the cover—had proven conclusively that horses were, from a military standpoint, useless in the high mountains. Since then, Rolfe had begun to think of transportation in terms of men and mules alone.

Still, one can appreciate the logic behind the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop, which arrived at Camp Hale in November. “Its men were to be the crack soldiers of the whole Mountain Training Center,” Jay wrote, “skilled alike in horsemanship, skiing, and rock climbing.” There were just two problems with this vision. One, while the cavalrymen knew horses, they knew nothing about skiing and climbing. Two, efforts to instruct them in the ways of the mountains fell decidedly flat.

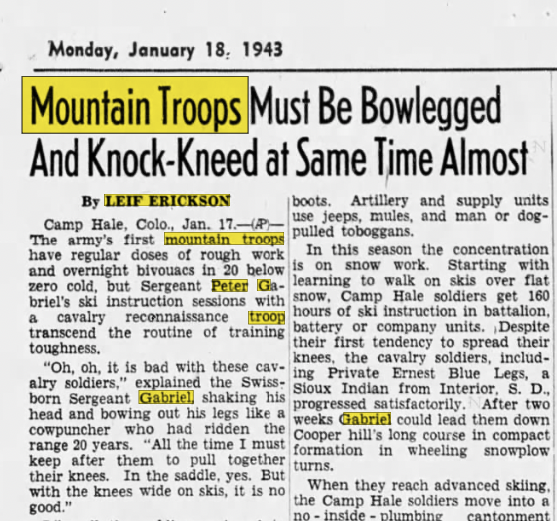

“Oh, oh, it is bad with these cavalry soldiers,” Sergeant Gabriel lamented in a newspaper article about the Troop, delivering his assessment, according to the author, while “‘shaking his head and bowing out his legs like a cowpuncher who had ridden the range 20 years. ‘All the time I must keep after them to pull together their knees. In the saddle, yes. But with the knees wide on skis, it is no good.’”

Despite the efforts of world-renowned experts like Prager and Gabriel to show the cavalrymen the ropes, they displayed, according to Jay, “little interest in learning how to ski and in trying to master rock climbing.” “[T]he personnel,” Jay continued, “proved to be both inept and unwilling to learn the skills necessary for mountain and winter warfare.” Jay’s assessment might seem uncharitable, but it’s affirmed by the results of the Army General Classification Test, in which thirty-eight percent of the cavalrymen tested below the medium intelligence level of the rest of the army.

By spring, it had become apparent to all involved – with the exception, perhaps, of the cavalrymen themselves – that it would be easier to replace the lot of them with the expert skiers and climbers already in camp. Efforts were soon underway to do just that.

But because this is the Army we’re talking about, that bewildering word, “Cavalry,” remained stuck in the middle of the unit’s name. Cavalrymen fit into the Army’s system. Climbers and skiers did not. Thus, even as the unit began to fill up with mountaineers, it remained the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop. “Considerable confusion,” Jay noted, “was constantly arising as a result.”

All but the most rabid students of the mountain troops will now want to attend to other matters for a few minutes while we soldier through the following minutia.

You’ll recall that the Army’s Tables of Organization (TO) detailed the exact organizational layout, number of personnel, and ranks for all its units. The Tables of Organization and Equipment (TO&E), meanwhile, added the material side, specifying the gear each unit needed to fulfill its mission. These two tables were the Army’s pre-approved blueprints for assembling and maintaining every aspect of its force in the midst of rapid expansion. Problematically, if it wasn’t in the TO or the TO&E, it wasn’t happening—and at this point in our story, neither a TO nor a TO&E had yet to be established for the mountain troops.

Both, however, had been established for the cavalry. Accordingly, the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop’s equipment and ratings—that is, the designated roles, ranks and associated pay grades for each position in the unit—were, well, all cavalry, and, as Jay pointed out, “ill suited for use in an instructor pool of mountaineers.” As a result, “motor sergeants’ ratings had to be juggled among skilled skiers; platoon officers’ bars had to be transferred to rock climbing supervisors; and no one knew what to do with the growing pile of .50-caliber machine guns, cavalry radio sets, and other tactical [items] that cluttered the small supply room.”

Fortunately, help was on the way. On April 25, 1943, Army Ground Forces sent a letter to General Rolfe authorizing a redefinition of The 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop’s combat mission as reconnaissance in mountain terrain. Captain Woodward was named its Commanding Officer, and the original cavalrymen and their horses were unceremoniously shipped out to Camp Carson.

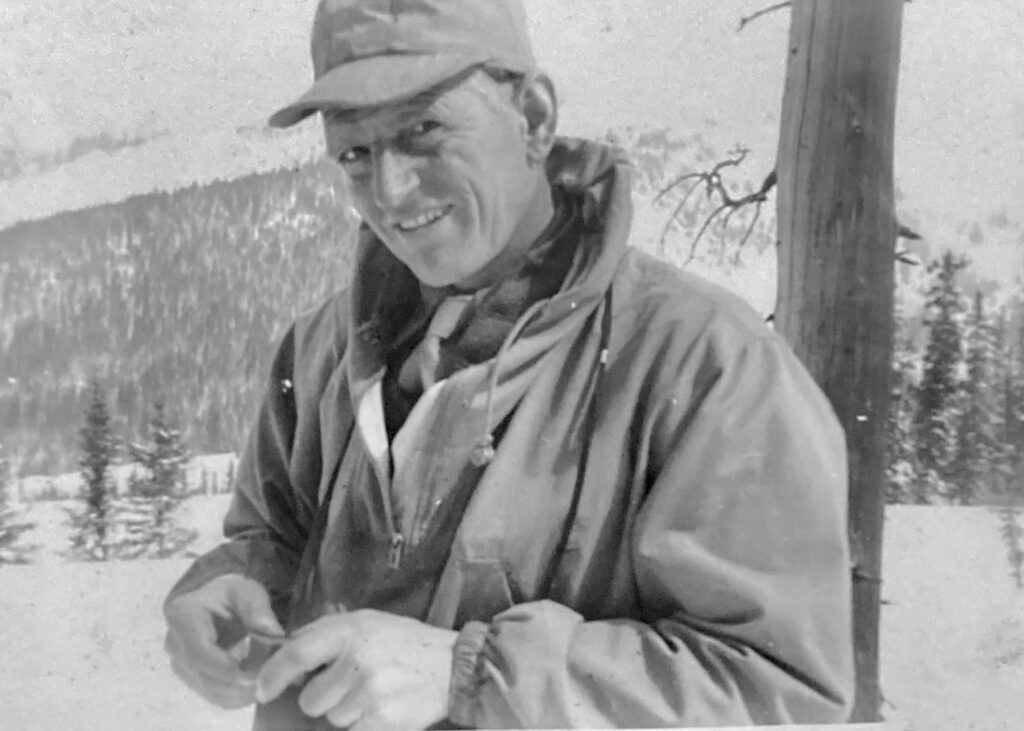

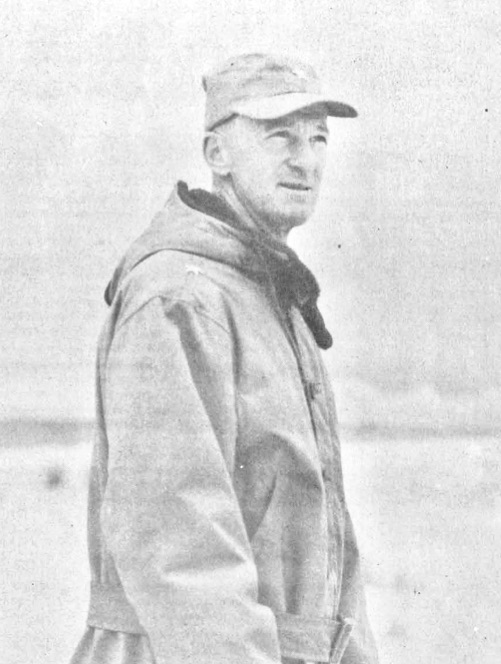

With the bureaucratic impediments more or less out of the way, Woodward turned his attention to choosing his instructors—and he had a growing number of candidates to choose from. As Jay noted, “Many of the world’s experts in skiing and mountaineering had [by that point] volunteered. A complete list of former champions [who’d] joined the mountain troops would read like a roster of the Olympic Winter Games.”

From said list, Woodward selected McCown, Prager and Gabriel and 40 other all-star personnel for the reconstituted troop as part of its initial team. They might not have had ratings in their new positions, and thus lacked a way to advance or get raises, but by spring, the nucleus of the instructor cadre was now in place.

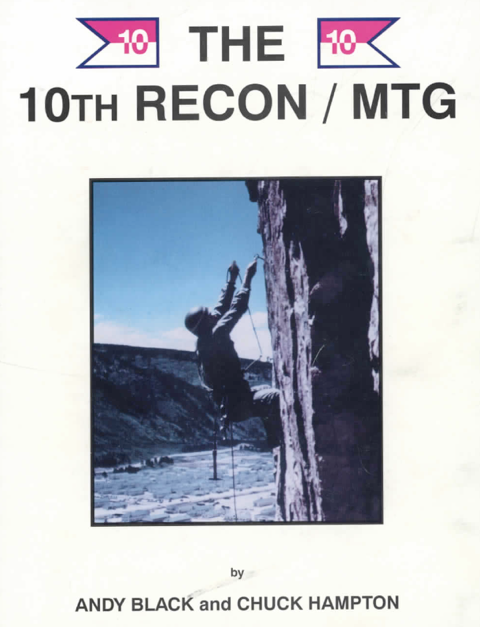

It would be difficult to overstate the importance the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop would have on the Division’s training. Come summer, the Mountain Training Center would be reconfigured into a new entity, The Mountain Training Group, and the flatlanders and Southerners who had been assigned to the MTC at its inception would be redistributed elsewhere in the force. The mountain experts who remained would become part of what Andy Black and Chuck Hampton, in their account of the cadre, referred to as simply The 10th Recon/MTG—shorthand for the two groups that we’re more than happy to adopt ourselves.

“When the US Army was developing a mountain infantry division at Camp Hale,” Johnny Woodward wrote in the Forward, “skilled ski and mountaineering instructors were assembled to provide the specialized training the 10,000-man division needed. Eventually, more than 200 men were involved in the work. Some were assigned to the Mountain Training Group (MTG), some to the 10th Recon, but their mission and duties were identical; they lived in adjacent barracks and ate together in one mess hall.”

Above and beyond the 280 instructors identified by Black and Hampton in their manuscript, I’ve identified an additional 92 who were part of one or both groups. They include most of the people we talk about in this episode—people like Jay, Woodward, Prager, Gabriel, Argiewicz, Link, Bedayan, Dawson, Brower and John McCown. But they also include men like Hal Burton and Luggi Foeger and Friedl Pfeifer and Charles Bradley and Robert Livermore and Fred Beckey. Never before in American history had such a collection of mountaineering expertise been gathered in the same place at the same time with the same objective: to teach the country’s first unit of mountain troops how to climb, ski and fight in alpine conditions and terrain. As they worked alongside one another, trading ideas and swapping insights that had previously been confined to the country’s insulated pockets of alpine knowledge, they created the basis for much of what we take for granted about mountaineering today.

And yet, for all the Olympic-caliber talent gathered at Camp Hale in the spring of 1943, most of it was proficient only in skiing—and as the snows began to recede from the hillsides around Pando, the need for expert climbers became more and more pronounced.

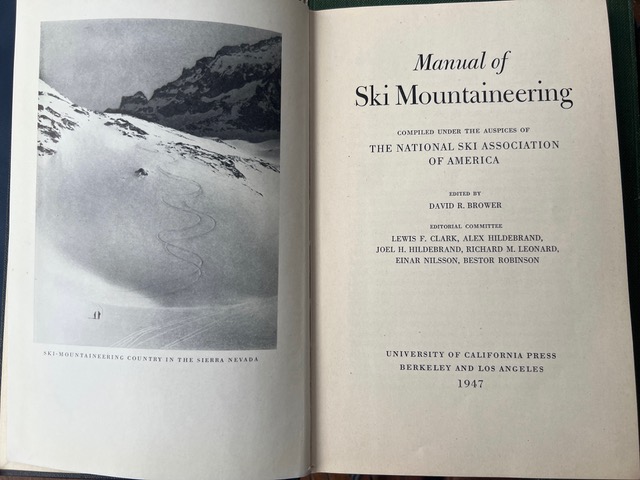

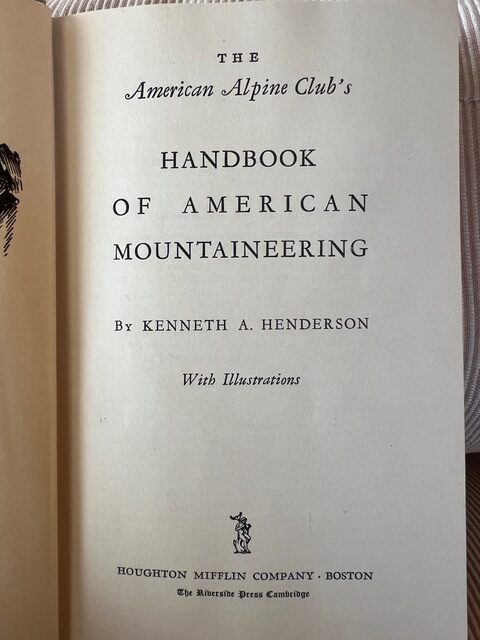

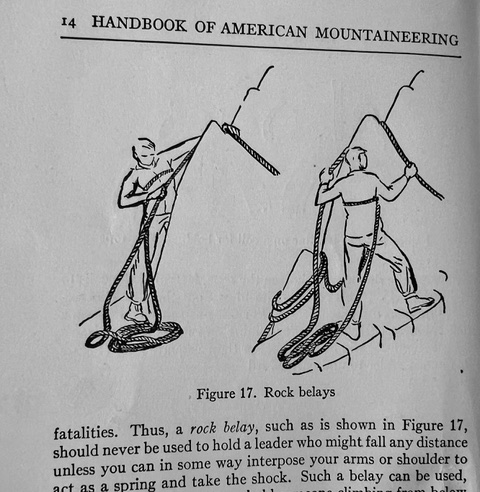

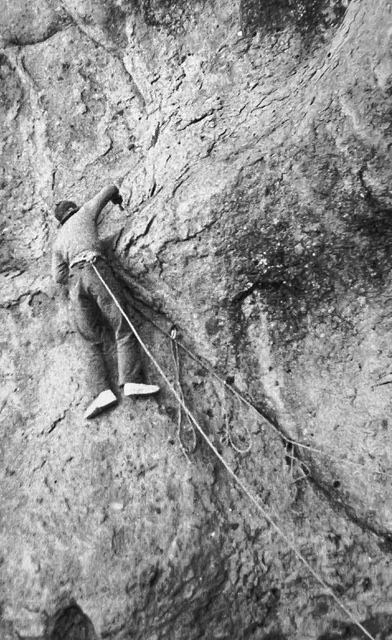

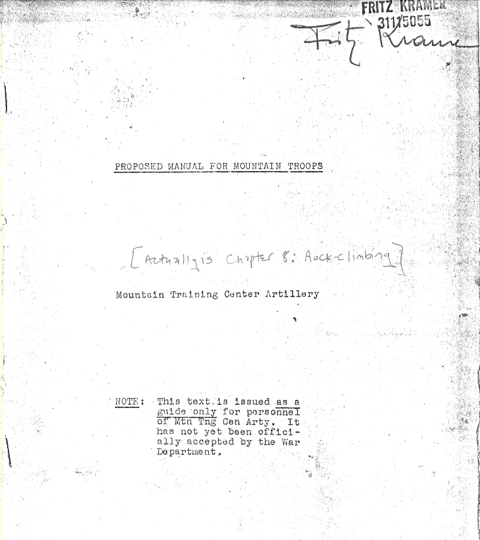

Brower’s rock climbing chapter of the Proposed Manual for Mountain Troops, the primer Woodward had directed him to develop, included belaying techniques that hadn’t made it into The Manual of Ski Mountaineering, the book he’d put together to teach the troops to ski. They hadn’t made it into Ken Henderson’s Handbook of American Mountaineering either. Both had been written to get the test force up and running—but much had changed since their publication, and Woodward had tasked Brower with weaving those changes into the new manual.

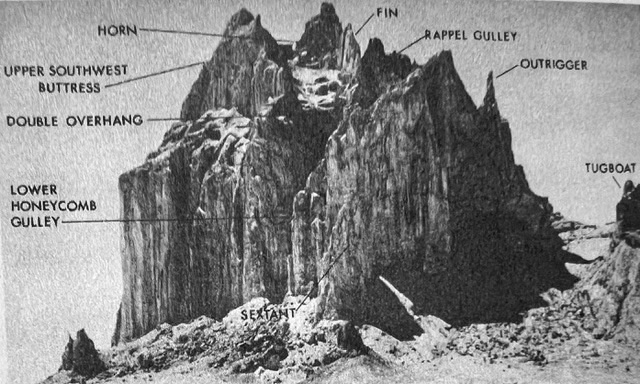

The techniques Brower was teaching John that day had been born out of the experiments of the Rock Climbing Section of the Sierra Club a decade before. While Californians like Glen Dawson, the author of bold new routes from the Sierra Nevada to the Alps, and Raffi Bedayan, Brower’s partner on the first ascent of Shiprock, were intimately familiar with them, the others were not. And if this nucleus of Woodward’s instructional cadre was to teach other teachers, practice was essential—and time was running short.

New recruits were stumbling into Camp Hale by the trainload, and rock climbing instruction was set to begin as soon as the snow melted from the cliffs. More pressingly, another operation, 1,600 miles to the east, was about to commence—and though they’d yet to learn about it, John, Argiewicz and Link would become some of its first technical advisors, with Brower and Prager close behind.

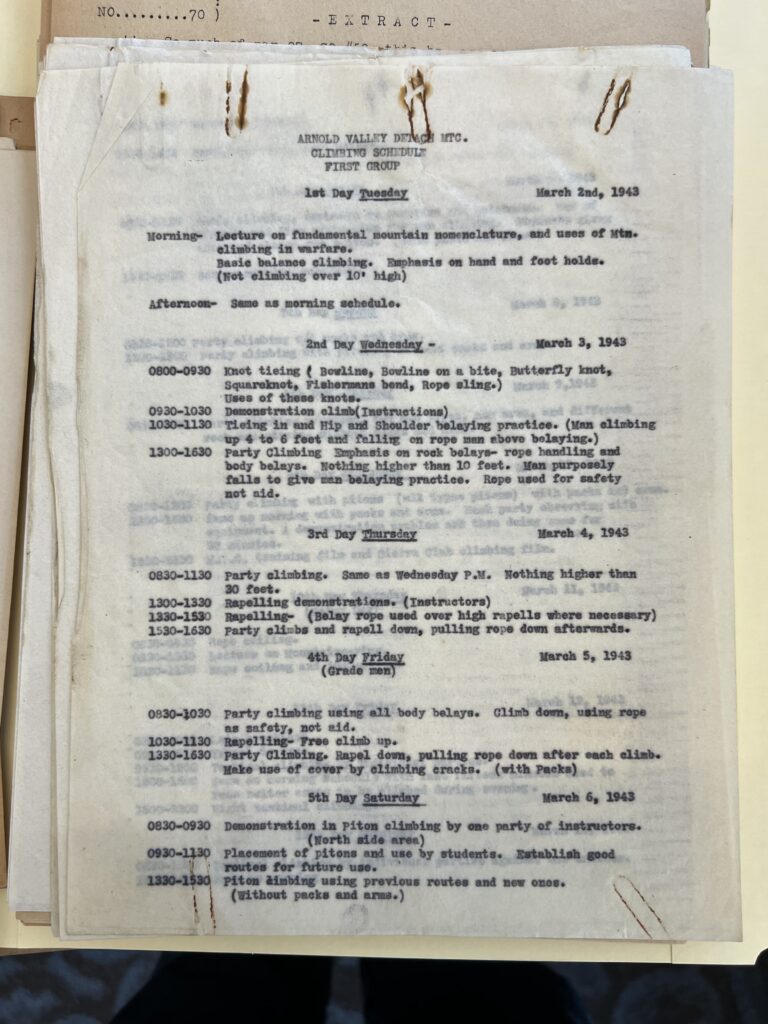

Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, had been scheduled for July. To tackle the island’s cliff-lined coast, Army Ground Forces had created what it called a “low-mountain training program” in Virginia’s Blue Ridge mountains, and directed the Mountain Training Center to find its instructors. The six-week climbing program was slated to start on March 1.

John McCown’s files in the Denver Public Library include a “Climbing Schedule” for what would come to be known as the Arnold Valley Detachment, which he and 1st Lieutenant Link would eventually come to lead. Dated March 2-14, 1943, it is the earliest known record of a training course for the Virginia program.

The course outlined in the schedule began with the basics—mountaineering terminology, the fundamentals of movement, knots, belays—before progressing rapidly through more and more advanced skills. By Day 3, students were learning to climb in teams of two and three and practicing rappels. By Day 5, they were learning to use pitons. Climbing with packs; climbing with arms; climbing on different kinds of rock; tactical climbing; aid climbing; fixed-rope traverses and finally a night-time tactical climb: the curriculum compressed skillsets that would have taken a civilian climber years to master into a two-week course.

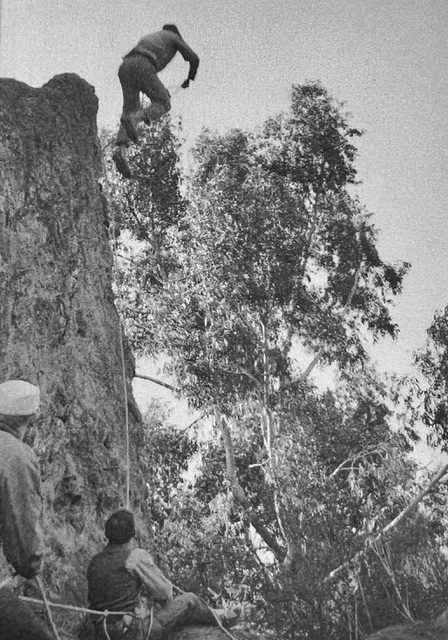

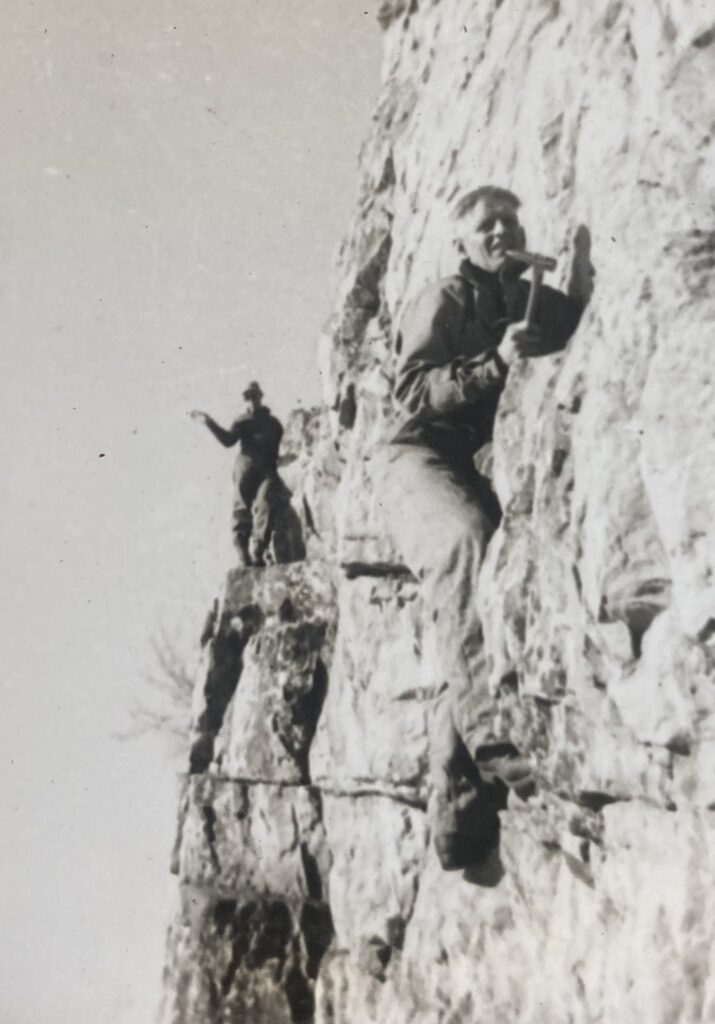

The MTC would have needed ample time to prepare for such an ambitious schedule, as well as a venue at which to work out the kinks. And for this it turned to the homely, scruffy, decidedly modest rock outcropping at the northeastern end of camp at the start of this episode.

The crag met the conditions Brower had laid out in his chapter.

“A high, difficult cliff is not the proper place to learn [to climb],” Brower had written. “Precipitous drops are apt to discourage a novice from learning by the trial-and-error method. Small local practice cliffs, short enough for a rope to reach from top to bottom, form a much more suitable environment for beginners. There, under the protection of a rope and without the frightening effect of height, the climber can experiment with each new climbing technique, even to the point of falling. After many falls, the climber gradually acquires an understanding of how far he can go without falling off.”

The cliffs, 100 feet high at their highest, are not pretty. I was there in February 2024 with today’s 10th Mountain Division as they went through practice maneuvers, and I gotta say, I felt bad for their predecessors. The rock is a metamorphic stone, black, lower-angled and fractured, with only a few steep sections that would have accommodated the kind of belay practice Brower was teaching John McCown. But what it lacks in aesthetic quality, it makes up for with its other attributes: an abundance of gullies, slabs, crack systems, and short, simple steps, and all of it a five-minute walk from camp. “[A]s many as a hundred men at a time could be taught the fundamentals of elementary rock scaling,” wrote Jay of the crag.

The cliffs would become the hub of the MTC’s first effort to teach its troops to climb. A Lieutenant Patterson, about whom nothing is known, organized a climbing school; he was soon replaced by Captain Woodward, who assembled members of the 87th Infantry and

Their expertise was greatly abetted by some of the Camp’s European mountaineers.

Joe Stettner was in his early forties by the time he arrived at Camp Hale in late 1942—too old to deploy overseas, but not too old to instruct. You’ll recall that he and his brother, Paul, mountaineering acolytes from Germany, had fled the rise of Hitler and the Third Reich in the mid-1920s, landing in Chicago and quickly turning their alpine expertise into some of the boldest climbs their adopted homeland had ever seen.

“Although inspired by skiers,” Jack Gory wrote in The Stettner Way, his biography of the brothers, “the military goal was to develop mountain troops. Thus the army sought elite mountaineers, as well as skiers. An emphasis was placed on rock climbing, ice climbing, crampon work and rappelling—all areas Joe had mastered long ago.”

Like all the European mountaineers, Joe could ski. In fact, he was proficient enough to be dismayed with the standard-issue Northland skis the Army had provided the mountain troops, so he had his brother Paul paint his personal pair white and send them to him to use at Camp Hale. But what made the elder Stettner invaluable to the encampment was his rock climbing experience, and he soon found himself selected to provide mountaineering instruction to officers and enlisted men alike.

In doing so, he became part of what he called the “International Brigade:” Germans, Swiss, Austrians, Swedes, Italians and Norwegians, ”most of whom,” noted Gorby, “were immigrants who had learned mountaineering and skiing in Europe. They were extremely anti-fascist and thus shared not only a common love of mountain sports, but also a common political viewpoint, which motivated them and molded them into a ‘tightly knit fraternity.’ Joe described them as a ‘bunch of tough guys.’”

Andy Black and Chuck Hampton, in their account of the 10th Recon, remembered the International Brigade as well. “The Europeans were mature guys,” they wrote, “many in their mid-thirties. They took an unrelentingly gloomy view of the world that compared starkly with that of the American instructors who, almost without exception, were fresh from university campuses.” You’d probably have a gloomy view of the world, too, if you’d been chased out of your home by a racist autocrat intent on stripping freedoms from millions of his compatriots and eliminating those he deemed “different,” but that’s not the point.

Like yin and yang, both groups of experts were necessary to get the job done. In addition to the extensive mountaineering expertise Joe and the international brigade brought to the table, they also had the roll-up-the-sleeves, get-’er-done attitude of American immigrants. Much as Walter Prager had helped then Lieutenant Johnny Woodward devise the log walls for climbing practice in the Ft. Lewis gravel pits the year before—establishing the first known artificial climbing wall in the process—Stettner would help resolve another conundrum in the mountaineering equation when he helped develop the world’s first known man-made glacier to teach the troops to climb ice.

Absent natural ice close to camp, Stettner proposed, according to Gorby, piping “water up a slope and over a cliff. The frozen ice became an ideal place to practice challenging ice climbing.”

“Logs were cut and stacked on a steep slope to simulate crevasses and seracs,” Jay wrote, “and then water poured constantly over them until a frozen, man-made ice cliff” took shape. The first effort, though, fell short: the engineers positioned the contraption on a south-facing slope, and it quickly melted out. A second glacier was then built on a north-facing slope, and platoons from the 87th Infantry, the Engineers, and the Signal Corps were soon cutting steps, driving ice pitons, swinging axes and kicking crampons, a complement to the rock climbing techniques they were learning on the stone.

The construction of the artificial glacier would be one of Stettner’s last acts at Camp Hale. His expertise as a metal worker had been requested by his former employer, Chicago’s Liquid Carbonic Corporation, which had just received a large defense contract. In late May, he showed motion pictures of his adventures in the Tetons to the camp. (Sidebar alert: the movies most likely included his 1941 first ascent, with Paul, of a couloir on the south face of the Grand Teton. In a series of events that would confound historians for decades, the couloir climbed by the Stettner brothers would come to be known, mistakenly, as the Beckey Couloir, after Fred Beckey climbed it with a team in 1948. Adding to the confusion, an adjacent couloir would be named after the Stettners, even though they never climbed it. Grab me in a bar some time and I’ll tell you the whole story.)

Joe Stettner was honorably discharged in June and returned home to continue working on his adopted nation’s behalf as part of the arsenal of democracy. Five months later, Paul would submit his paperwork to the National Ski Association, join the mountain division just after it left Camp Hale , then serve with distinction when it deployed to Italy.

Despite Joe’s departure, his glacier ice would live on, becoming part of the so-called Mountain Obstacle Course, which combined all the features of the camp’s regular obstacle course with the rock and ice work to test the troops’ proficiencies. Those who passed were certified as Military Mountaineers.

But just as it had taken time for the MTC to learn that “ski training on packed slopes served by ski lifts,” as Jay put it, “is only valuable for teaching fundamentals,” so too would they learn that “[t]he same applies to assault cliff climbing taught on near-by school cliffs. Further extensive practice on long trips over rugged terrain [was] necessary.”

The Mount of the Holy Cross, Mt. Elbert, and Mt. Massive, among other 14’ers, rose above the foothills just to the west. Soon enough, the instructors of the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop and their student soldiers would begin climbing these iconic peaks in summer as well as winter, executing mountaineering traverses across the spine of the Sawatch Range and embarking with regularity on alpine missions that deepened their expertise as it baptized them in the brotherhood of the rope and whipped them into the toughest soldiers the Army had ever seen.

But that, dear listener, is a thread of our story that we’ll save for our next episode.

For now, we’ll focus on the instruction of the instructors, which needed to occur at that cliff above Camp Hale—asap.

When it was published, Ken Henderson’s Handbook represented a watershed moment. “This volume,” Henderson wrote in the preface, “is the first attempt to provide the American climber with a practical description of climbing technique, and to apply the knowledge of a broad field of climbing experience to American conditions.”

“Because of the need for speed in the original production of this work to assist the United States Army and its plans for the training of mountain troops,” he went on to add, “the preparation was largely the work of a single individual.”

That individual was Henderson himself. And given his standing as one of the country’s foremost climbers, one would assume the book would have been, as he put it, “truly representative of American mountaineering thought and experience.”

It is distinctly curious, then, that it omitted some of the nation’s greatest contributions to the field—those made by the Californians.

Climbing is not a suicidal death wish. It is a pursuit that allows a person to encounter, decipher and, with proper preparation and a dash of luck, overcome a range of physical, mental and emotional challenges, often in sublime natural settings. The ability to return home after the fact is predicated on systems that safeguard the wellbeing of the practitioner. Foremost among them is the belay, the system and technique used to protect the climber in case of a fall.

“Belays,” Henderson observed in Chapter 1 of his Handbook, “are what make roped climbing safe. To be safe, belays must be able to stand a strain and still not break the rope.”

Henderson’s book was written at the end of an era. Until then, climbing ropes had been made of natural fibers such as manila, sisal, hemp, even silk. That would soon change as John and Brower and their peers began to test the first nylon ropes during their maneuvers in Virginia. At the time Henderson published his handbook, though, natural fiber ropes were still the standard, and their ability to hold a fall was limited.

“New climbing rope,” he wrote, “will stand a strain of over a ton, but a 175-pound man falling more than twelve feet … will put sufficient strain on the rope to break it if the rope is belayed firmly on a fixed point. Misunderstanding of this fact has resulted in many fatalities.”

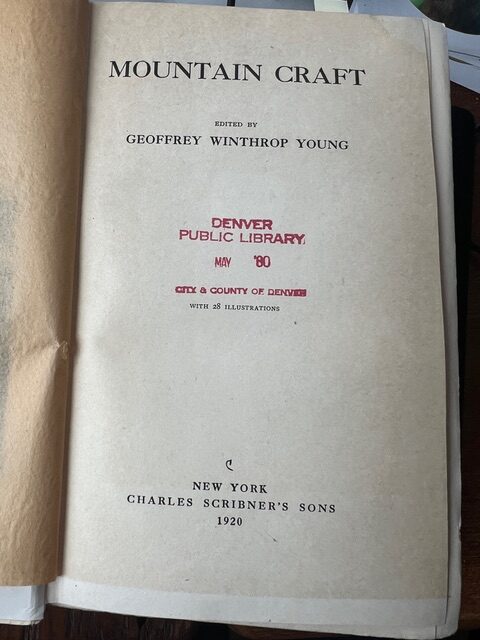

Before the publication of Henderson’s Handbook, the definitive source of climbing in America was a twenty-year-old British book: Sir Geoffrey Winthrop Young’s 600-page compendium, Mountain Craft. In his bibliography for the chapter, Henderson cites Mountain Craft along with four other books, all published in 1934 or earlier, and all from Britain, Germany and France, as his source materials.

Mountain Craft had as its cardinal rule a single edict.

“A leader,” Young wrote, “does not fall. It is the first condition of his hegemony that he must not. His fall from any height must mean injury to himself, and may involve the whole party… [T]o fall as a leader is to fail lamentably and egregiously as a mountaineer.”

There was a reason behind Young’s decree. Stories of falls that either snapped the rope or plucked an entire team from the face of a climb punctuated the pages of both the British and American alpine journals. But a key factor behind these catastrophes was the ability—or, more accurately, the lack thereof—to catch a fall properly, and thus mitigate the forces to which the rope was subjected.

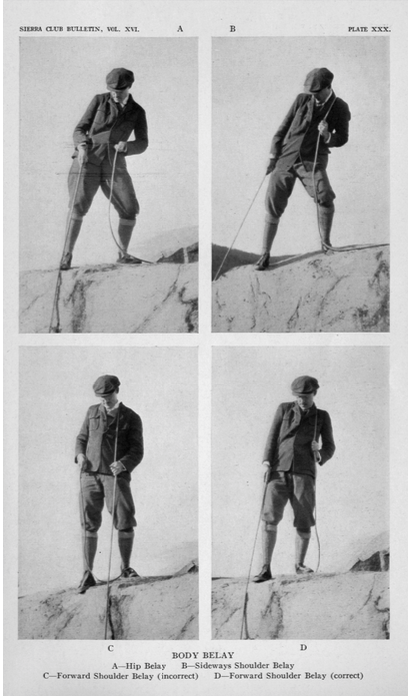

To Young, the rope existed not to safeguard the life of the leader, but to facilitate the advance of the other members of the party. The leader’s role was to climb a section of a route, and then to bring up his partners via one of two methods of belay. The first was the “direct belay,” “where the rope in action,” as he put it, “connects directly on to or round rock.” The technique, he pointed out, was never to be used to belay a leader, as the forces generated by a fall would be almost certain to break a rope. In fact, he continued, “As a protection to a man following up a rock the direct belay is almost equally unsound,” for the ropes of the day were unlikely to survive even those forces.

The second method, and the only one Young could recommend with even marginal confidence, was the “indirect belay,” “where,” he wrote, “some form of human spring is interposed between the active rope and the solid rock.”

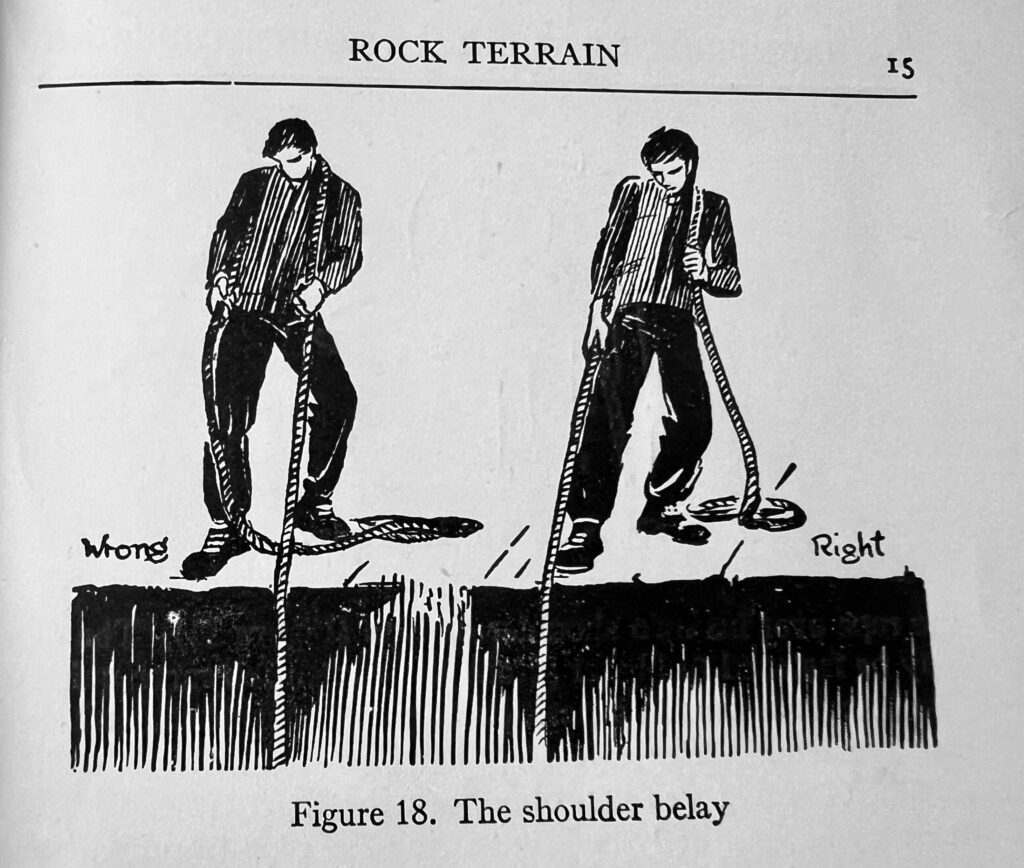

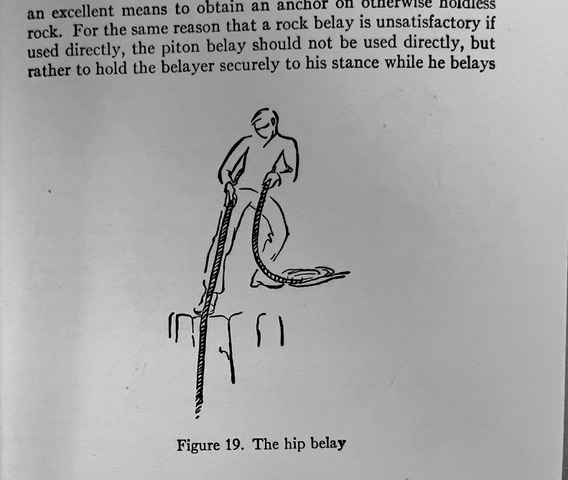

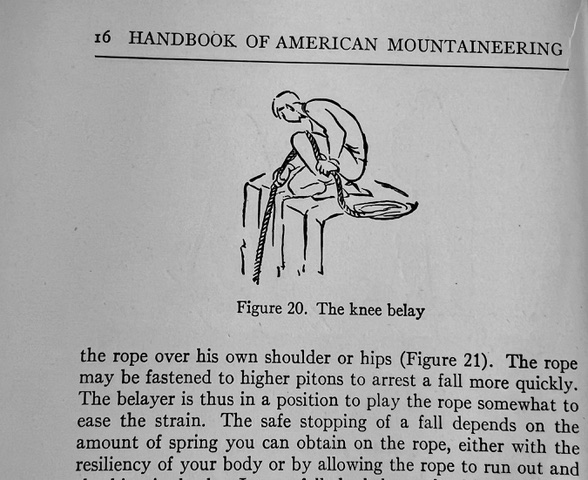

The spring was the belayer himself, who absorbed the force of a fall with his own body. This was achieved by positioning the rope over his shoulder, across the back and down to the climber below, or, preferably, high on one’s hips, and assuming what Young termed a “strong stance.”

If either method sounds alarmingly unsophisticated, that’s because they were.

As the late, great climbing pioneer John Middendorf put it in his two-volume study, Mechanical Advantage, Young’s indirect belay “simply recommended using the human body and grip to resist the forces of the fall rather than quickly tying the rope off to a fixed anchor….” Such a belay could arrest, at most, a seven- to ten-foot fall. Anything greater would exceed the ability of the belayer to absorb, and the rope to withstand, the forces generated by the drop. “Without a surefire way to keep people safe in case of a fall,” Middendorf wrote, “leading anything more than about 10 feet above an anchor was essentially soloing….”

Young’s indirect belay was also, Middendorf noted, “about the extent of the knowledge of dissipating the energy of a shock load for most climbers and climbing instructional book authors in 1933.”

Henderson’s coming of age had occurred amidst an ethos curated by Young and his book. At the same time, Henderson had pushed the boundaries of the possible with his own climbs, establishing routes that were longer, bolder and more technically advanced than anything previously done on American soil. As a council member of the American Alpine Club, he was profoundly plugged into the insular climbing scene. If anyone could write an up-to-date and entirely indigenous manual American mountain troops could use to learn how to climb, it was him.

And his handbook did indeed capture much of the state of the art between its covers. It detailed movement over rock, ice and snow terrain, the inherent dangers of such travel, and how to extricate oneself from disaster when it struck. Mountain weather, map reading, cooking, camping, equipment and a host of other topics essential to moving safely in the mountains: it was all in there, and the vast majority of it was up to date.

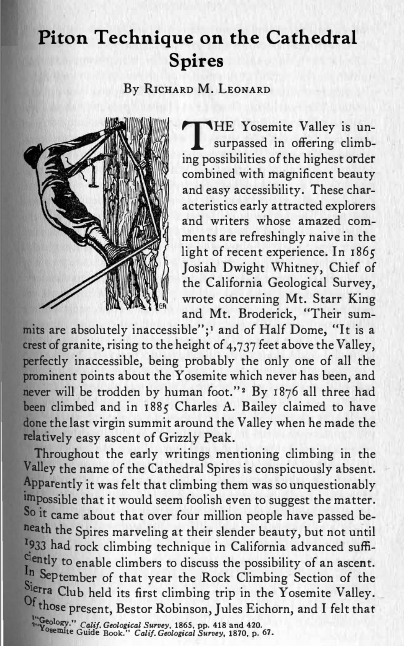

But its opening chapter on rock climbing had a decidedly Old World take on the key technique of belaying, one that ignored the revolutionary advances on the topic that had been introduced by the Californian climbers nearly a decade before.

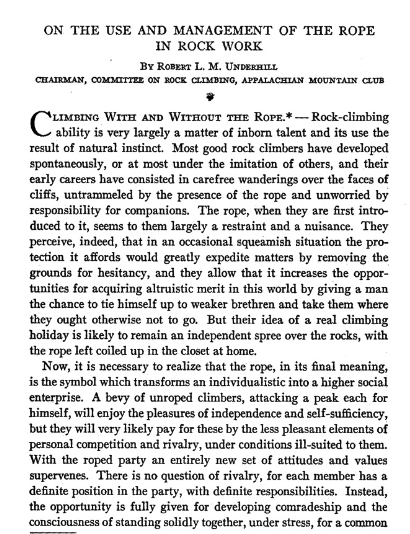

In 1931, Henderson’s climbing partner, Harvard philosophy professor Robert Underhill, had published an article entitled “On the Use and Management of the Rope in Rock Work” in the Sierra Club Bulletin. The article, which detailed the standing shoulder and hip belays then in vogue in the Alps, inspired the Sierra Club to invite Underhill to the Sierra Nevada to teach the latest techniques in person. His visit, in turn, inspired a rash of first ascents in the Sierra Nevada by climbers like Dawson that marked some of the most difficult rock climbs the range had yet seen.

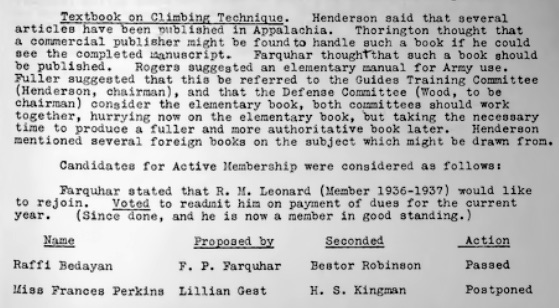

Inspired by Underhill’s visit, Dick Leonard, a young attorney of 25 from the Bay Area, organized the world’s first formal study of the belay that winter. His partners in the experiment were fellow attorney and mountaineer Bestor Robinson, 35, and a 21-year-old climbing prodigy named Jules Eichorn. Robinson, of course, had been the driving force behind The Manual of Ski Mountaineering, the book David Brower had edited for the Sierra Club, and when war broke out, both Robinson and Leonard would go to work besides Bob Bates and Bill House at the Quartermaster General’s office, developing gear, clothing and rations—and, in Leonard’s case, the first nylon climbing rope—for the mountain troops. Leonard’s rope, which was three times as strong as natural fiber ropes, would fundamentally change the equation for American climbers after the war.

A decade earlier, though, they’d embarked upon their study for a simple reason. “[T]he standard methods of belaying,” as Middendorf put it, “were more theoretical than practical”—that is, they hadn’t been tested. The Sierra Club, of which Leonard, Robinson and Eichorn were members, was in thrall to Young’s edict, and had accordingly distanced itself from the harder rock climbs they’d come to love.

“The European philosophy,” Leonard would later write in his memoir, “was that nobody could hold the fall of a leader. To put it in another way, if you were climbing the mountain, and you have an experienced person who leads the climb, he has a rope to the second man and the third man. Even if they do not have experience, the second and third are protected. But if the first man, the leader, should fall, say, 20 feet, he would fall 20 feet down to where the second climber was and then another 20 feet below him. If the second climber were on a ledge, that would be 40 feet before anything could be done about it. To my logical, legal mind that did not seem sensible because it meant that if that one person fell, all three would be killed.“

The Californians decided to figure out exactly what the ropes and pitons and carabiners and belay methods of the day would hold. By the spring of 1932, they’d given themselves a name—the Cragmont Climbing Club—and begun a systematic practice of falling and belaying that would change how we climbed forever.

As attorneys, Leonard and Robinson were persuasive by nature. They brought the Sierra Club their preliminary findings, argued their case that climbing, when well-informed, could be done safely, and won. As a result, the Club allowed them to begin a Rock Climbing Section. Leonard and company folded the Cragmont Climbing Club into the new entity. The RCS, as it came to be known, became a laboratory for the most advanced climbing experiments in history.

Yosemite legend Steve Roper was a climbing pioneer, guidebook author and historian of the nascent scene. “Since safety was uppermost in everyone’s mind,” he wrote, “the RCS climbers, now numbering fifty-two, spent much of 1932 and 1933 learning to belay and rappel properly…. Over and over again, for hours at a time, the neophytes jumped off overhangs to be caught by ropes tended by well anchored and well padded belayers.”

These practice sessions were both fun and social. Above all else, though, they were practical. For the first time, climbers were attempting to understand what exactly they could get away with on the rock. They had a powerful motivation: the great walls of Yosemite Valley, which had never before been attempted, were a relatively short six hours away. Noted Roper, “Leonard, by 1933 the prime mover of the group (one could, without much argument, call him the father of California rock climbing), insisted that no one was going to climb in Yosemite until he or she had mastered the proper techniques. That this took a few years may seem strange, but these folks were either serious students or young professionals; neither group had the time or money, especially at the height of the Depression, to go climbing often. In fact, they thought it a good season if they went to the local rocks eight times a year and to the High Sierra once.”

Their experiments quickly bore fruit. For one, they revealed the limitations of the European body belays, which, in originating from either the shoulders or on the upper reaches of the hips, created a high center of gravity that was inherently unstable, and thus unsafe. As Leonard pointed out, a climber belaying his second up a wall using a shoulder belay would simply be yanked off the wall if the second fell. As a result, the RCS lab rats shifted the rope lower on the hip; to lower the center of gravity even more, they sat.

They also experimented, as Roper put it, “with letting the rope slip slightly around the waist when bringing a falling leader to a stop. This ‘dynamic’ belay eased the strain on the two humans and the rope itself, the weak link in the equipment chain.”

Over the course of their experiments, Leonard, Robinson and the other members of the RCS “extended their safety zone,” as Middendorf put it, from ten-foot free falls to falls up to 20 feet.

If the experiments of the RCS were unprecedented, so were the results. By the time they embarked for Yosemite on Labor Day weekend 1933, their members were, as Roper put it, “the most overtrained rock climbers in America.” By the following spring, Leonard, Eichorn and Robinson had used their dynamic belay system to make the first ascent of Higher Cathedral Spire, a magnificent, 600-foot granite needle that marked the opening chapter of American bigwall climbing.

“The idea that the famous imposing pillars of Yosemite granite could be ascended Alpine style, and with minimal risk, fundamentally changed the mindset of the climbing game,” Middendorf observed. Leonard published an article on the RCS experiments in the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Bulletin that same year, describing the mechanics of the dynamic belay and the new, safer methods of climbing steep rock. As the news spread, the American rock climbing mind was collectively blown, leading, as Middendorf put it, “to historic 1930s climbing achievements in North America, including Shiprock and Mount Waddington….” As a result, “a whole new breed of American rock climber was spawned….”

Which brings us back to Ken Henderson, the Handbook of American Mountaineering, and David Brower’s rock climbing chapter in the Proposed Manual for Mountain Troops.

In his book, Henderson advocated for the high-center-of-gravity-belays popularized by the Europeans twenty-two years earlier. The revolutionary contributions of the Californians receive, at best, an oblique mention.

It’s difficult to see how the omission could have been anything other than intentional. Henderson’s climbing partner Robert Underhill had inspired the Californians to begin their study. When Leonard had published the RCS findings in the Appalachian Mountain Club Bulletin in 1934, Underhill had been its editor. Henderson would almost certainly have known about the new techniques from him.

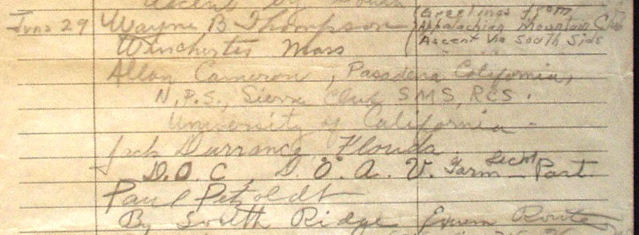

He would have had a personal motivation for mastering the skillset as well. In 1936 he’d partnered with the legendary Jack Durrance to pioneer a 1,200-foot direct start to the Grand Teton’s Exum Ridge . The resulting route was so fine, Roper included it in his legendary guidebook, Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. Though it checks in at the now-modest grade of 5.7, it’s steep and intimidating and gives 5.10 gym climbers a religious experience with regularity even today. Durrance and Henderson climbed it in Ked sneakers, a hemp rope tied in a bowline around their waists, with only a few pitons for protection. The pair were two of the finest climbers in the country, as strong mentally as they were technically; but it’s almost inconceivable to imagine them launching up such a route without the Californians’ more dynamic belaying methods at their disposal.

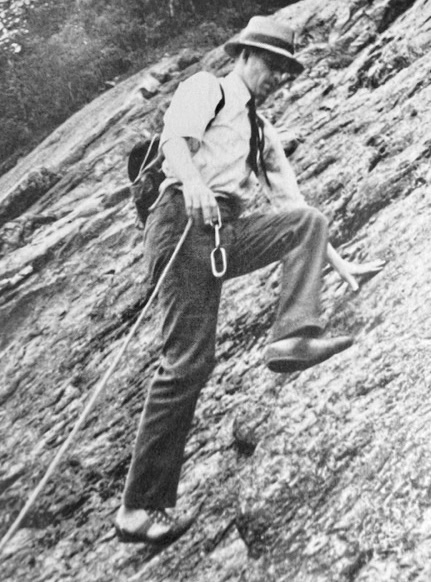

Fortunately for both the mountain troops and American climbing after the war, David Brower had been a beneficiary of the RCS experiments, and had complemented his education with more than three dozen first ascents in the Sierra Nevada, not to mention the first ascent of Shiprock and a 1935 attempt on Mt. Waddington. By 1942, his insight on the topic was among the most advanced in the world. So when then-Lieutenant Woodward enlisted him in the development of the Rock Climbing chapter for the Proposed Manual for the Mountain Troops, Brower made sure to address Henderson’s omission.

“Recently,” Brower wrote, “a new technique of belaying has been developed which represents an advance and will be used in military climbing. It is the dynamic belay. As in the indirect belay, the belayer, firmly anchored and securely placed, runs the climbing rope around his body, preferably his hips. When a fall takes place, instead of holding the rope firmly as the shock occurs, the belayer first allows the rope to slide around him. The falling climber is then brought to a stop by progressively increasing the friction of the rope as it moves around the belayer’s body. Rather than trying to stop the fall immediately, he overcomes the momentum gradually by a braking action, with great decrease in the shock that would otherwise result.”

Gone are the old-school, sketchy belays of Henderson and the Europeans. In their place are the basis for the kind of climbing we do today.

To be fair, Henderson was a civilian. Though his book’s publication was meant to help the Army with its new mountain unit, its content dealt primarily with concerns shaped by civilian mountaineering.

Brower’s chapter on Rock Climbing dispensed with the civilian in the first sentence. It was by, for and about the military climber.

“The untrained mountain soldier has two foes,” he wrote, “the enemy and the mountain. But he can make a friend and an ally of the mountain by learning to know it. The mountain can give him cover and concealment, points of vantage and control, even, at times, food, water, and shelter. This course can serve to introduce the soldier to the mountain. It is then up to the soldier, through his own wit, to make a better acquaintance, so that when he goes into combat he can concentrate on the enemy.”

Dismissing peacetime concerns did two things. In preparing the soldier to move as efficiently as possible over technical terrain, it eliminated any quarrels about ethics. And in focusing on climbing’s fundamentals, it shattered the norms of who belonged in the mountains in the first place.

As Continental climbers at the end of the 18th century had undertaken harder objectives in the Dolomites and Alps, they’d begun using pitons to create points of protection in the rock to safeguard passage. As we covered in Episode 2, the results had ushered in a revolution in the sorts of routes climbers were able to tackle—but Young and the Brits were having little of it.

“Artificial aids,” Young intoned in Mountain Craft, “have never been popular with us. If a climber does not feel safe…, he ought to practice on rock which he can climb, not spoil rock he cannot with blacksmith’s leavings. …Any man who feels when he looks at a passage that he wants more protection behind him than the character of the rock allows… should not attempt the passage at all. If he decides to take the risk, he should do so only on his own account, and unrope from his own party.”

To a generation of British climbers raised on Young’s musings, the use of pitons was “unsportsmanlike” if not outright immoral. By the time Henderson wrote his book, perspective on the matter had evolved somewhat, at least on this side of the Atlantic, but the British reservations continued to influence his perspectives.

“The use of pitons opens up many interesting possibilities,” Henderson wrote on the topic. “They provide belays where natural ones are lacking and they make safe an otherwise dangerous route. They can also be used for direct aid—i.e., handholds or footholds or support for the climber—although there is considerable controversy as to whether such use is ‘sporting.’”

Boulderdash, countered Brower. “Pitons are the greatest contribution to mountaineering safety since the introduction of the rope,” he wrote in the Rock Climbing chapter. With their use, “the biggest danger of climbing—the danger of serious injury when a leader falls on difficult rock–can largely be circumvented.

“In some climbing circles,” he continued, “the use of pitons, either for direct aid or for safety, is frowned upon as ‘unsporting.’ Whether unsporting or not, piton technique makes climbing immeasurably safer and is retained on this basis alone, and again, as with the use of the rope for direct aid, the soldier must choose the quickest, safest route, and leave ethics to the theorist.”

The Proposed Manual of Mountain Troops was never fully completed. With our advisory board’s help, we’ve located Brower’s rock climbing chapter, as well as the chapters on Military Skiing, Organizational Equipment, and Snow Avalanches. According to Jay, outlines were developed for sections on mountain medicine, first aid, the transportation of casualties in the mountains, mountain meteorology, and the aneroid barometer as well, but they’ve evaded our efforts to find them.

The unifying theme of the sections we’ve located is practicality. They were written to help soldiers do soldierly things in the mountains as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a result, they did away with many of the considerations—practical, philosophical and otherwise—that had previously handicapped mountaineering’s evolution.

Take the mountains themselves. For Young, and to a lesser degree for Henderson as well, the mountains, in all their terrible glory, were the end-all, be-all of ascent. Rock climbing was but a stepping stone, one that paled in comparison to the greater craft.

Brower dispenses with such perspectives almost immediately.

“In the past,” Brower wrote, “the prevailing view was that long, easy routes on actual mountains, later more difficult climbs, were best for the development of mountaineering judgment. A fall at any time was naturally discouraged as bad form. But no amount of easy or difficult climbing without a fall will allow one to set up a reliable margin of safety; without having fallen on difficult rocks, the climber never knows exactly how near or far he may have been from a fall.”

The members of the Cragmont Climbing Club had learned the ropes, as it were, on the boulders of Berkeley, California. The troops at Camp Hale would begin their studies on the scrappy cliffs described at the start of this episode. The soldiers preparing for the invasion of Sicily, meanwhile, would undergo their training on small cliffs in Virginia and West Virginia, with no intention of climbing any mountains at all. It was the first time in American history that rock climbing had become an end in and of itself.

Had Brower’s contributions been limited to the public introduction of the dynamic belay and the sanctioning of pitons and the embrace of rock climbing for its own sake, their importance would have been extraordinary. But he also introduced a numerical system that categorized mountain outings into six classes. Such classifications were not included in Henderson’s Handbook—but there they were in Brower’s chapter, ensuring GIs learned about them as well.

“A classification of climbing difficulty,” he wrote, “serves two purposes. It guides the soldier in striking his balance between safety and progress, and it provides reconnaissance groups a measure by which to convey the difficulty of terrain to units which are to follow, that they may tackle the mission with adequate time, equipment and personnel.” It was an eminently practical point, and it is the basis for how we talk about climbs today.

Another key element to safe travel in the mountains is the ability to communicate with your partner. When you’re on a ledge, your partner is 100 feet above you, and the winds are whipping, it can be next to impossible to hear what she’s saying—which is why we have climbing signals.

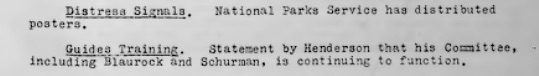

For reasons now lost to the mists of time, Henderson made no mention of them in his Handbook. It wasn’t as if he hadn’t had the chance to consider them.

In the mid-1930s, the National Park System had gotten skittish that climbers equaled accidents, and accidents equaled bad press. As a result, they’d begun considering banning climbing from places like Mt. Rainier altogether. As part of his work with the American Alpine Club, Henderson had developed a Committee on Guides’ Training to stave off NPS concerns. The training included a series of distress signals guides could use to call for help if and when disaster struck. The system of communication, which included “three audible or visual signals to be answered by two signals,” had been adopted by the Club in 1937—but not a word about it appeared in the Handbook.

The pioneering climber and guide Paul Petzoldt had given the matter some thought as well. In his book, Teton Tales, Petzoldt noted that he’d begun developing a set of signals when he first arrived in the range in the mid-1920s. His system used short, distinct words—“on belay, up rope, slack, climbing”—that were not only, as he put it, “simple to understand, but … could be distinguished by the number of syllables. It made them more readily interpreted, even if they weren’t clearly audible in the wind.”

“When I joined the ski troops in World War II,” Petzoldt wrote, “I was put in charge of working out the standard operating procedure for mountain evacuations.” We’ll get to Petzoldt’s arrival in a future episode, but for this one we’ll focus on what he said next. “We used those signals then,” he wrote. “[T]hat’s when they got introduced to the Army. It wasn’t long,” he concluded, “before the signals or slight variations of them were being used all over the United States and in England.”

Petzoldt’s assertion that he’s the guy that introduced climbing signals to the Army has just one small problem: he didn’t arrive at Camp Hale until November 1943, a year after Brower included them in the Manual.

Could Brower have learned of Petzoldt’s signals from Sierra Club members who picked them up while visiting the Tetons? Sure. A quick glance at the Grand Teton’s pre-war summit register finds more than two dozen Sierra Clubbers on top, including Allen Cameron, whom Petzoldt guided up the Exum Ridge alongside a young Jack Durrance on June 29, 1936. Maybe Cameron took Petzoldt’s signals back to California, where they became part of Brower’s lexicon. Be that as it may, Petzoldt wasn’t the first to introduce them to the mountain troops; Brower was. “On Belay,” “Climbing,” “Tension,” “Slack”—some of the first words a climber learns today—all got their public debut in his chapter.

Why did Henderson leave climbing signals and classifications —not to mention advanced belay techniques—out of his book? Depression-era climbing was a rarified affair, guarded by aristocratic walls that kept the unwashed masses out. Petzoldt, a ranch kid from Idaho, was the exception: a gifted climber who underwrote his passion by bringing others into the hills as a guide. For the general public, climbing required both time and money—resources few of them had. Not so the gentleman climber, who was accustomed to retaining guides like Petzoldt for his jaunts in the mountains—even if he had to hold his nose while doing so.

“The average guide,” Young wrote in Mountain Craft, “is a peasant, with the limitations that frame peasant virtues. … He is a child, with a precocious development on a special line which gives him his one standard for manhood in general…. The guide as we know him is hill-born, hill-bred—that is, a child, with a child’s capacity for becoming much what we make him—a companion, a valet or a machine–and with a child’s suspicion and shyness, which he hides under an appearance of professional reserve or a formal politeness.”

Henderson was from the New World, which had ostensibly liberated itself from the shackles of a class-based society, but he was still the product of an upbringing that could afford his Harvard education and summer trips to the Alps and the tutelage of guides for his Alpine adventures. Even his attire reflected his privilege: he was famous for climbing in suits. While his Handbook dispensed with a lot of British pretension, it was nonetheless written by an aristocrat. Who else had time to climb at the end of the Depression?

Well, middle-class climbers like David Brower, for one. Brower’s father worked for the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company; his mother was a homemaker. Jules Eichorn was the son of German immigrant parents. Dick Leonard had been born in Ohio before attending college at UC Berkeley. Of the bunch, only Bestor Robinson, whose father was a prominent attorney, is known to have come from an upper-middle-class background. As we’ve discussed elsewhere in this series, Robinson had a habit of rubbing people the wrong way; perhaps the publication of the Manual of Ski Mountaineering two months before Henderson’s handbook had pissed him off. Or maybe Henderson just didn’t like Californians.

Whatever the reasons, we can only look back with puzzlement at what Henderson chose to include, and omit, in his Handbook—and can only view Brower’s arrival at Camp Carson in the fall of 1942 as a sort of divine intervention. Because of him, John McCown and more than 200 other instructors of the 10th Recon and MTG would go on to learn about safe belays, solid anchors, climbing classifications, climbing signals and other fundamentals of the pursuit we now take for granted. They, in turn, would teach thousands of others the art of vertical ascent, both on the cliffs around Camp Hale and in Virginia and West Virginia. Because of their instruction, the pursuit’s popularity would explode after the war.

Thanks in no small part to David Brower, the democratization of the mountains was off to a proper start.

And now we bid adieu to David Brower, who, together with Raffi Bedayan, was off to Officers Candidate School. We also say goodbye to the many fine people of Camp Hale, at least for the next couple of episodes, for in early March, 2nd Lieutenant John McCown, Private Artur Argiewicz Jr. and eight other members of the 10th Recon flew to Washington DC, took the train to Lynchburg, Virginia and from there made their way to the Blue Ridge Mountains to set up the Army’s low-mountain training program. They would be followed shortly thereafter by 1st Lieutenant Ed Link and Staff Sergeant Peter Gabriel, as well as recently promoted second lieutenants Brower and Bedayan. We’ll pick their story up in earnest in our next episode, which will be devoted entirely to their roles in preparing American GIs to invade Sicily, and its seismic effects on American climbing after the war.

We’ll say goodbye to the 87th as well. In early May, the Army sent the 7th Infantry Division to Attu in the Aleutian islands to repulse the Japanese invasion. The unit landed on May 7 unopposed, but the fanatical resistance that followed resulted in the deaths of 2,351 Japanese and 539 American soldiers over the course of 18 days. The horrifically cold, wet weather did as much to undermine the American effort as the Japanese resistance, forcing the Army to realize it needed troops trained to fight in adverse conditions if it wanted to succeed—and that meant it needed the men of the 87th, the country’s most experienced unit of winter warriors.