Available only to Patrons, this Unabridged version of Episode 13 continues our deep dive into America’s high-altitude military experiment as it unfolded at Camp Hale during the pivotal winter of 1942–43. The episode details the Mountain Training Center’s daunting task of expanding the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment into the country’s first full-fledged mountain division—all while battling altitude sickness, low morale, brutal conditions, and an influx of recruits who often had no love for winter or the mountains.

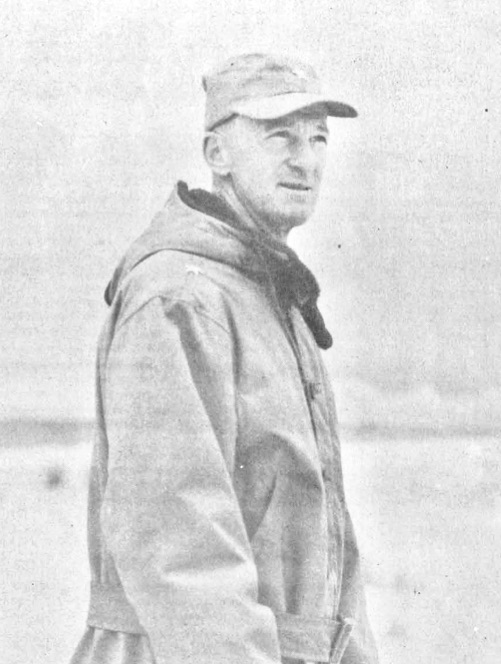

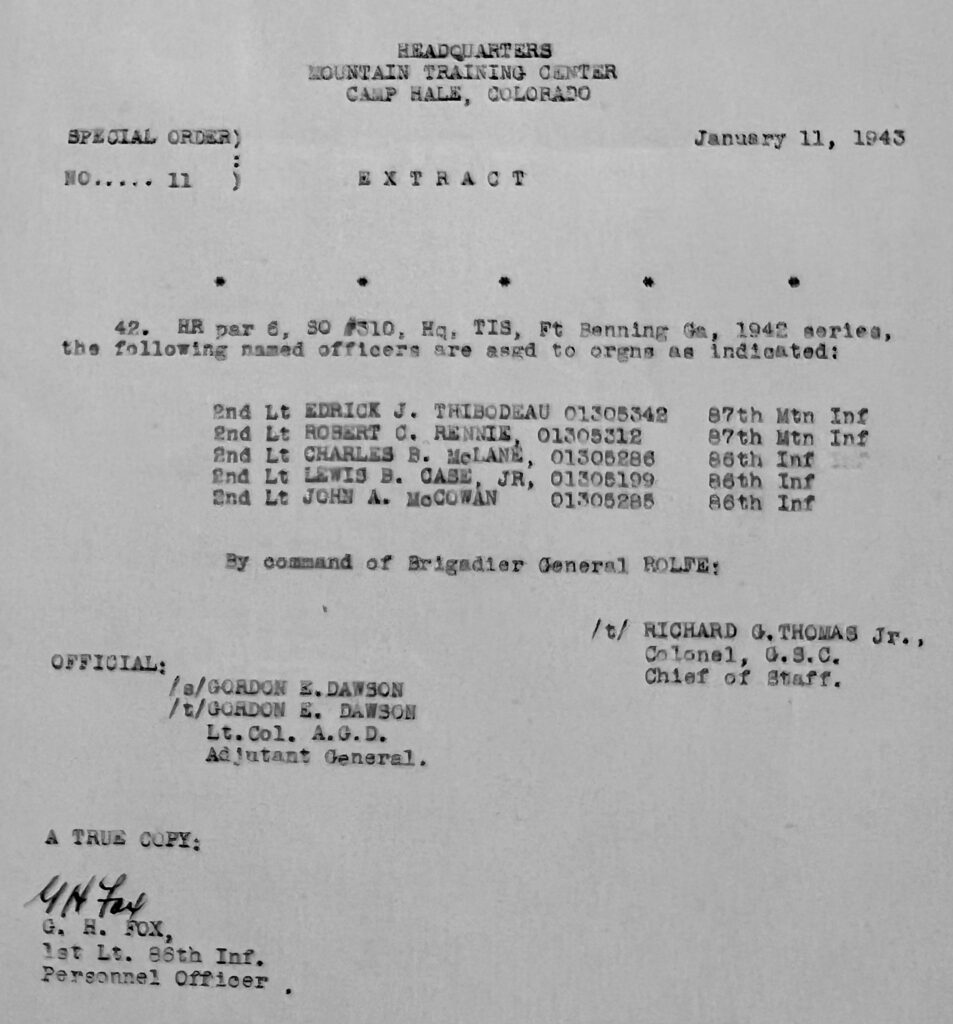

We follow the journey of John McCown, newly minted as a second lieutenant, as he navigates the frustrations of early Camp Hale training; the media blitz that turned America’s “mountain warriors” into national icons; and the growing pains that would culminate in the disastrous Homestake Peak Maneuvers—an exercise so fraught with frostbite, blizzards, and equipment failures that it earned comparisons to Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow.

Highlights include:

- Interviews with Ninety-Pound Rucksack advisory board members Lance Blyth, David Little and Sepp Scanlin provide behind-the scenes insights into the developments covered in the episode.

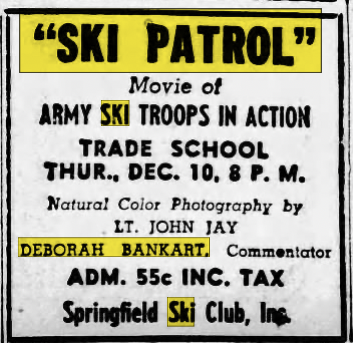

- Recruitment Push: Minnie Dole’s National Ski Patrol System, John Jay’s PR push, Deborah Bankart’s Ski Patrol film tour and a nationwide enchantment with the mountain troops helps find thousands of new recruits with genuine winter experience.

- The Birth of the 86th Regiment: McCown transitions from the elite 87th to the newly formed 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment, helping to shape the next chapter of mountain soldiers.

- Special Missions: We explore the special missions that exported the mountain troops’ expertise to other units and locations—including the Columbia Icefield Expedition that resulted in Studebaker’s Weasel, a revolutionary over-snow vehicle that would become essential to the training at Camp Hale.

- Homestake Peak Maneuvers: A grueling February 1943 field exercise exposes critical flaws in training and leadership—ultimately drawing scrutiny from Army Ground Forces and prompting a scathing report from the unit’s founders and advisors.

This episode also examines the cultural foundations being laid for America’s post-war outdoor recreation boom—how the expertise of climbers like David Brower, combined with the Quartermaster Corps’ innovations, helped democratize the outdoors for future generations.

Resources & Links:

- Support the show on Patreon for early access, bonus interviews, and illustrated episode transcripts.

- Visit christianbeckwith.com for more episodes, resources, and behind-the-scenes content.

- Learn more about the 10th Mountain Division Foundation and the 10th Mountain Alpine Club, two of our project partners.

Welcome back to Ninety-Pound Rucksack. I’m your host, Christian Beckwith, and today we continue our examination of America’s military mountaineering experiment as it unfolded over the winter of 1942-43 at its high-altitude encampment at 9,200 feet in Colorado’s Pando Valley. Camp Hale, as the base was called, was where the various threads of the test force began to come together into the country’s first full mountain division—but as we’ll soon see, the process was as complicated and at times as tortured as the American war effort overall.

It has taken me nearly six months to research and write this and the following episode—so thank you to all the listeners out there who have been waiting patiently for it to drop. I can honestly say I wouldn’t have been able to do it without the support of our incredible advisory board; our partners, the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, the Denver Public Library, the 10th Mountain Division Descendants, and the 10th Mountain Alpine Club; and most importantly our patrons. These loyal listeners give five or ten or fifteen dollars a month to support the project, and our ability to continue to do so is in large part thanks to them. In exchange, we create behind-the-scenes content such as in-depth interviews and illustrated versions of each episode just for them. If you want to deepen your 10th Mountain Division experience, or you just want to support the show, go to christianbeckwith.com and click the bright orange Patreon button. I can’t tell you how invaluable our patrons are to our storytelling efforts—so thanks again to them for helping make our project possible.

And of course we’re also indebted to our sponsors: CiloGear and Snake River Brewing, for their support.

I live in Jackson, Wyoming, in the shadow of the Tetons, and the other day, a friend and I went for a ramble on the Grand Teton’s Upper Exum Ridge. The route is one of America’s so-called “fifty classic climbs” for a reason. The setting, more than a mile above the valley floor, is stunning, the rock is gorgeous, the route-finding an intricate puzzle of stone and snow and ice. It’s an outing that demands fitness, alpine expertise and the right gear—which is why I brought my CiloGear Worksack.

The longer I use my CiloGear pack, the more I appreciate its comfort, light weight and intuitive design. Is it expensive? Hell yes—until you factor in that you’ll never have to buy another pack, because CiloGear packs are virtually indestructible. They’ve got everything you need for an alpine adventure and nothing you don’t.

CiloGear is not just for civilians, either. Their sister brand, CG Strategic, makes the world’s best mountain warfare packs and military equipment as well. From missions in the alpine to cutting edge pre-hospital systems, CiloGear and CG Strategic are your bombproof, form-fitting, featherlight pack solutions. They’re also 100% owned & operated in the USA.

If you want one killer pack for the rest of your life, visit cilogear.com—that’s c-i-l-o gear.com—and check them out. Use the code rucksack to get 5% off your purchase and CiloGear will match your purchase with a donation to the 10th Mountain Alpine Club, a collective dedicated to advancing alpinism in the spirit of the 10th.

I’d love to say that when we got down from the Grand we had an ice-cold beer from Snake River Brewing waiting in the truck, because nothing takes the edge off a thirteen-mile, fourteen thousand foot day like one of their Earned It IPAs—but we didn’t, because we’d forgotten them! Total rookie move. It’s gutting to realize you’ve failed to bring the beer when you’re partway down because then you spend the rest of the descent thinking about how good it would have tasted if you’d remembered. In my case, I had about six miles of jarring downhill to fantasize about a deliciously cold Earned It IPA, which is my favorite. There’s even a creek near where we parked the truck, and I could have filled a mesh bag with Earned Its and stashed them for an ice-cold adult beverage upon our return—but no, because I’d blown it. All I can say is the next time you’re headed out on an adventure, don’t do what I did: make sure you remember to bring your favorite beer from Snake River Brewing to celebrate once it’s over. Whether you’re reaching for an Earned It IPA or a full-flavored Pakos IPA or a Jenny Lake Lager, Snake River Brewing’s lineup of award-winning craft beers is the perfect ending to a great day in the mountains. They’ve been brewing their beers here in Jackson since 1994, and you can find them across the west, in Wyoming, Colorado, Idaho, and Montana—or better yet, visit the Brew Pub in downtown Jackson and complement one of their refreshing brews with some of their great food.

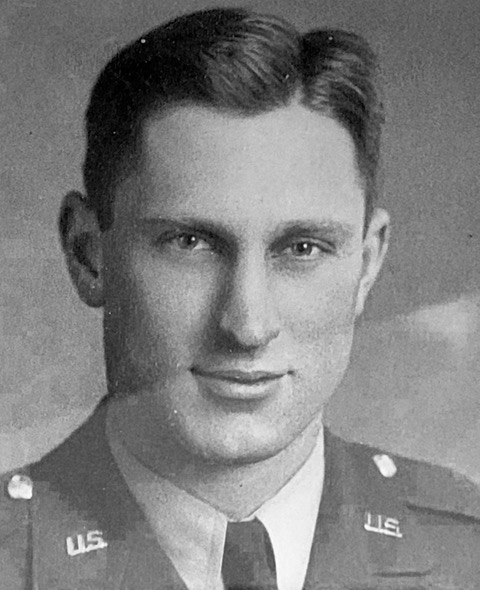

And now, with no further ado, let’s catch up with our hero, John McCown, who, freshly minted as a second lieutenant, is taking stock of his situation midway through his very first week at Camp Hale.

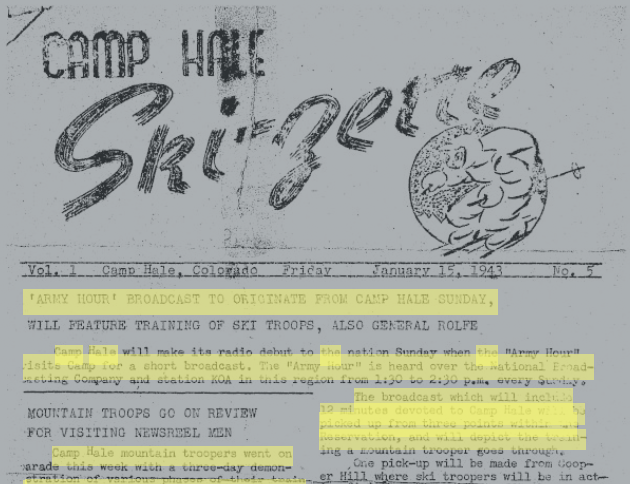

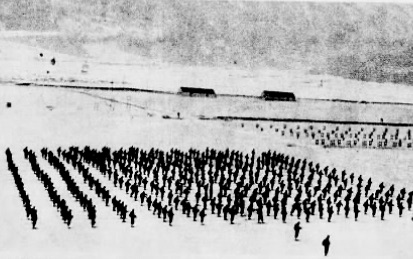

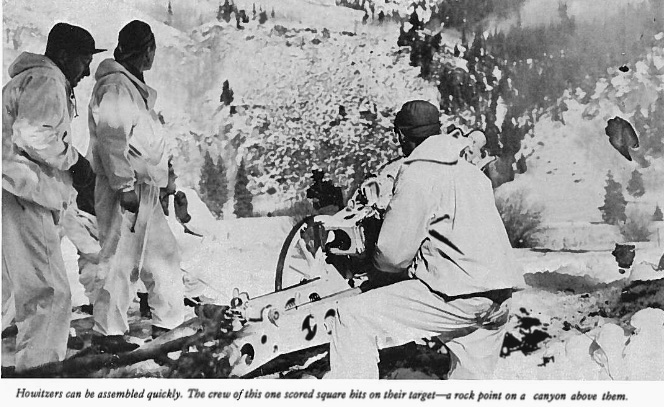

MOUNTAIN TROOPS GO ON REVIEW FOR VISITING NEWSREEL MEN

—From The Camp Hale SKI-ZETTE, January 15, 1943

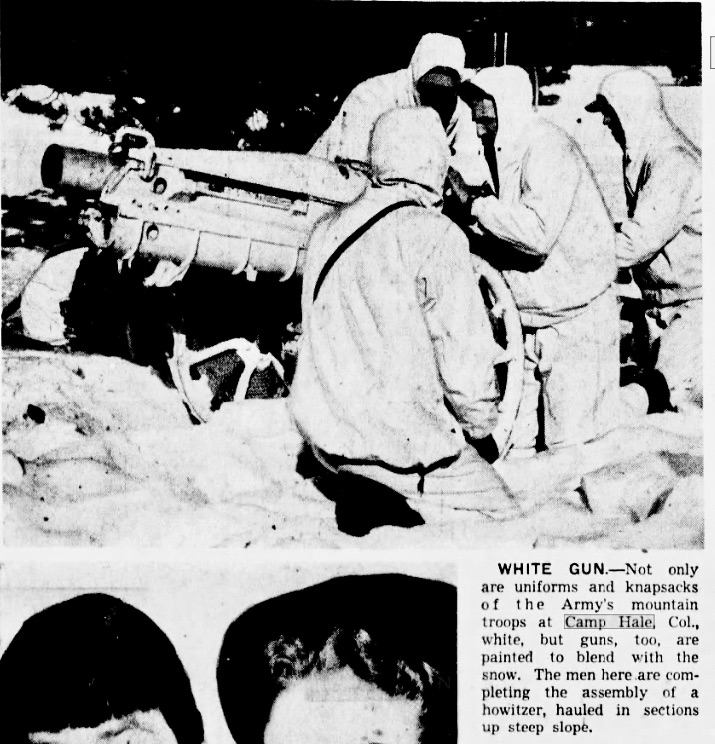

Camp Hale mountain troopers went on parade this week with a three-day demonstration of various phases of their training…. Cameramen from four newsreel companies … were on hand to record the demonstration in picture and in print…. Ordinary practice sessions furnished material for the cameras as the artillerymen demonstrated how they move their pack howitzers through the snow, assemble them and fire, then dismantle them and continue on their way. They also set up camp in the snow showing the advantages of [their] white tents…. Tuesday afternoon the newsmen were taken to Cooper Hill where a group of approximately 80 skiers appeared on the horizon [wearing] white parkas and … skied down the hill through the trees and disappeared into the valley below, all recorded by the movie cameras….

The men furnished many opportunities for fine action shots, believes Lt. John Jay, public relations officer of the [Mountain Training Center], who accompanied the photographers.

“This,” 2nd Lieutenant John McCown muttered, the dry air scratching at his throat, “is bullshit.” Three days, he’d been at Camp Hale, and all he’d been doing was waiting: waiting to move artillery while cameramen got in position, waiting to pitch a tent while reporters stumbled through the drifts, waiting to lead a fake charge over snow-covered ridges while film crews angled for their shots. He’d dropped out of law school for this, signed up the moment the Japs hit Pearl Harbor, then spent the better part of a year ping-ponging from California to Washington to Georgia, learning to lead men into battle. He was sick of waiting. He wanted to move.

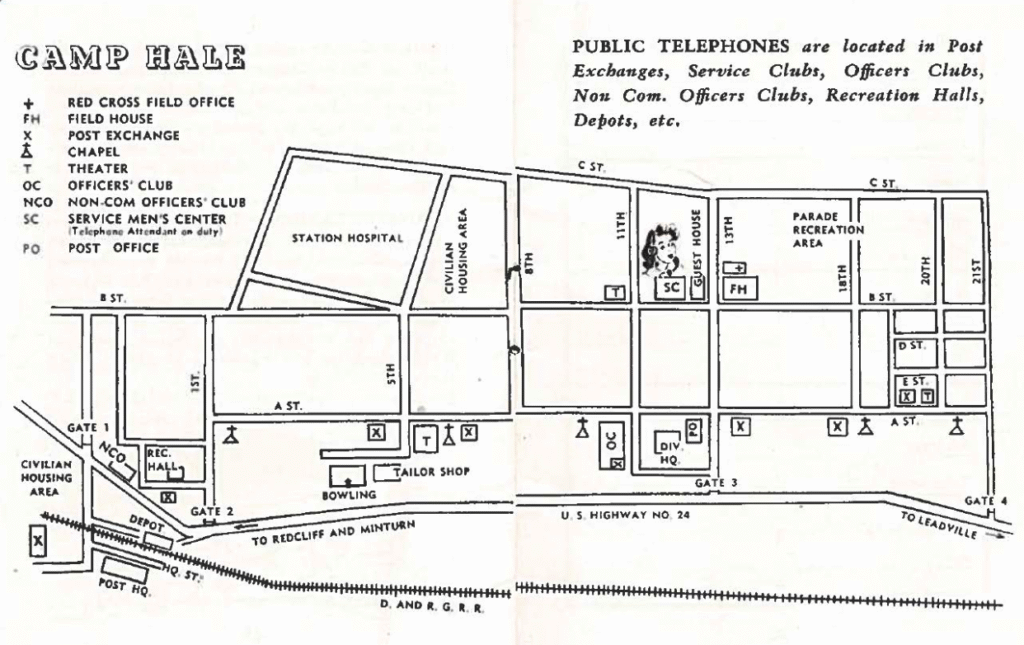

A gust of wind funneled down the street, cutting into his cheeks. He could barely make out the outlines of the Mountain Training Center Headquarters through the blanket of coal smoke hanging over the valley floor. Foothills rose beyond the grid of barracks, hiding the high summits of the Sawatch and Ten Mile ranges that ringed the camp. From the west, a rifle crack sounded from the firing range, followed by another, and then a volley. He pulled the hood of his parka tighter around his face and leaned into the wind.

John couldn’t believe he’d spent three months at Ft. Benning for this. Officer Candidate School had been brutal, a crash course in Army hierarchy and outdated protocols, but he and Charlie McLane and Worth McClure and their comrades from the 87th had thrown themselves into it with everything they had. Their country needed them. More importantly, General Rolfe needed them. He’d hand-picked them to help him lead his test force, and if that meant suffering abuse at the hands of old Army regulars and mastering tactics that had more bearing on the Great War than this one, so be it.

But beating Hitler in the Alps or the Japanese in the Aleutian Islands, which they’d just invaded, meant they had to get to work now—and all John had done for the better part of a week was stand around while the cold chased the blood from his fingertips, yet another prop in the War Department’s propaganda machine.

A column of white-clad soldiers emerged from the haze, double-timing it toward him, skis slung tips-down over their shoulders, a cameraman shadowing them from the back of a jeep. John shook his head, exhaled sharply, and quickened his pace.

It wasn’t that he didn’t get it. He did. General Rolfe needed men, and for that he needed to sell the mountain troops, and for that he needed stories—and what better stories were there than the warriors in white training to fight amidst the frigid shadows of Colorado’s highest peaks. Still, as John bounded up the MTC Headquarter stairs, stomped the snow off his army-issue boots and swung open the door, he was over the Army and its goddamned waiting, and ready to begin.

The room’s warmth hit him like a wave. An aide led him down a hallway and knocked at a door. A voice, harried but familiar, called, “Come in.”

Behind a battered desk buried in film canisters and folders sat Lieutenant John Jay. Dark smudges ringed his eyes, but the grin that spread across his face as he looked up swept away all of John’s frustrations in a heartbeat.

“Good to see you,” Jay said, standing and extending a hand.

“You too,” John replied, pulling off his gloves. He took in Jay’s drawn face and cluttered desk as he glanced around. “You look… busy.”

Jay laughed and rubbed the back of his neck. “I look beat, is what I look like. But yeah. Between the news crews and the brass, it’s been nonstop. Glad you’re here. We need all the help we can get.”

Same old Jay. The kid who used to narrate his ski films over the family Victrola was now telling the Army’s story to the nation. Meteorologist, photographer, gear tester—whatever Rolfe needed, Jay delivered. He’d been grinding since Ft. Lewis, and it lifted John’s spirits to see he hadn’t eased up.

“Sorry about the assignments,” Jay continued, waving at his messy desk. “But we’ve got to give the newsreel boys something. The quicker we get the word out there, the faster we fill up.”

John nodded. “Whatever you need,” he said. As he took in the weight in Jay’s eyes, any lingering urge to grumble disappeared. “Just point me at it.”

Jay’s grin softened. “Well… I’ve got good news and bad news,” he said as he returned to his chair. “The good news is—you’re going skiing.”

John arched an eyebrow. “And the bad news?”

“It’s for the cameras.”

“Well, that’s a relief,” John said, half-smiling. “I was starting to worry I might actually have to put all this training to use.”

Jay shot him a sympathetic look. “Soon, John—don’t worry.” He reached for a folder from a dangerously tall stack. “Beer later?”

“Sure,” John said. “I’m buying. Looks like you could use one.”

“Or three,” Jay snorted, already buried in his paperwork.

John stepped back out onto the MTC porch, the acrid sting of coal smoke hitting his nostrils. Troops moved past in small groups and loose columns, heads bowed into the cold. A Jeep coughed as it drove past, belching a plume of exhaust that joined the smoke rising from hundreds of barrack chimneys. Somewhere above, the mountains loomed—or would have, had they not been swallowed by the smog.

Rolfe needed recruits, and Jay was helping find them. That was the job. Seeing his old friend buried in paperwork had reminded John of his own commitment. He’d traded a law degree for a rifle and a chance to serve his country. The waiting was over. He took the stairs two at a time, hood down, chin up, welcoming the cold on his face like a challenge.

By the time John walked out of Jay’s office, the unit he’d joined nine months earlier had nearly tripled in size. Marching before the cameras might not have been why he’d signed up for the mountain troops, but it was a mission-critical part of their evolution, as was he.

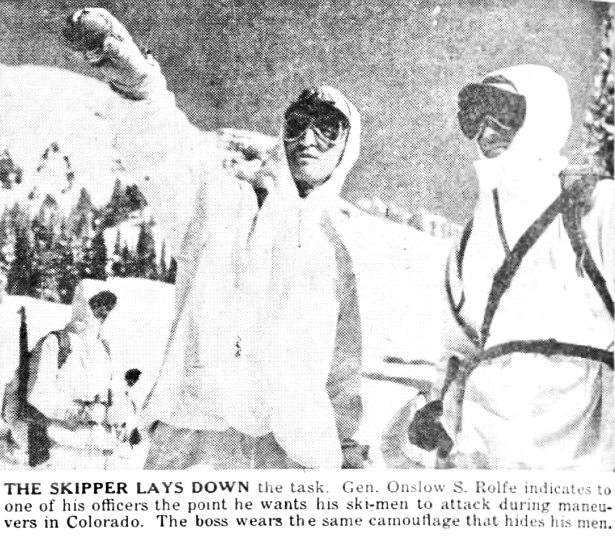

Until this point, the development of the test force had followed a relatively straight line. The 1941 German invasion of the Norwegian port town of Narvik, wherein German mountain troops held off an Allied counterattack four times their size for three months above the Arctic Circle, followed by the Italian army’s disastrous experiences in the Albanian mountains, where a lack of winter training had resulted in the decimation of their forces, had convinced the War Department that it needed a break-glass-in-the-case-of-emergencies unit for cold weather and mountain warfare. In late 1941, it had selected Colonel Onslowe Rolfe, the red-headed, New Hampshire-born, West Point educated World War I hero better known as “Pinkie,” to oversee an experiment: what would it take to develop a unit of mountain warriors out of a flat-land, warm-weather military?

Under Pinkie’s command, the 1st Battalion (Reinforced) of the 87th Mountain Infantry had been activated on November 15, 1941, at Ft. Lewis, Washington. Like hundreds of collegiate climbers and skiers around the nation, John had dropped out of school after Pearl Harbor to join the test force, becoming part of the unit in April after completing his basic training. A second battalion had been added on May 1, followed by a third a month later. By the time Colonel Rolfe had sent John to Officer’s Candidate School at Ft. Benning in September, the 87th had become the Army’s first full Mountain Regiment with a strength of 3,000 men.

That, though, was still 12,000 men short of the Army’s objective. It had decided to expand the 87th into a full division—and it wanted it done by summer. Closing the gap was one of Lieutenant Jay’s priorities, which meant it was one of John’s as well.

Camp Hale represented the next logical step in the journey to mountain warfare proficiency: a purpose-built encampment surrounded by treeless summits where American troops could learn to fight in alpine terrain. To run it, the Army had turned to the only candidate qualified for the job: Colonel Rolfe.

Here’s our advisory board member Sepp Scanlin.

[Sepp Scanlin] Along with the decision to move larger-scale mountain training to a new mountain base, they’re gonna move the leadership that has kind of developed that training concept along with it. Rolfe is seen as the premier overseer of mountain training for the army. At that point, he was the guy that was there at the birth. From his original time at the 87th, he has become the face of mountain training for the army.

Rolfe’s advancement had been facilitated by a number of factors.

[Sepp Scanlin] He hasn’t done anything poorly, he’s managed to navigate the politics of it all—and just like everyone else at this stage in the army, they’re promoting pretty rapidly.

To put that in civilian terms, Rolfe hadn’t messed up, he could deal with the military’s malarkey, and he was a qualified, talented officer in the middle of war—which is to say he was in the right place at the right time. Amidst the country’s unprecedented military ramp-up, competent personnel were moving quickly through the ranks out of necessity. Case in point: John McCown, who had been promoted from an enlisted man to an officer in a little over a year.

To oversee the division’s development, the Army had activated the Mountain Training Center at Colorado’s Camp Carson in September 1942. Here’s Sepp Scanlin again.

[Sepp Scanlin] So the Mountain Training Center is the organizational construct that is put in place to provide the framework to build the division out of. They can’t just go from 87th Regiment to 10th Infantry Division Alpine. They have to have some bridging strategy. So the Mountain Training Center is that bridging strategy.

As our advisory board member Lance Blyth explains, the MTC included a host of units critical to the future division’s success.

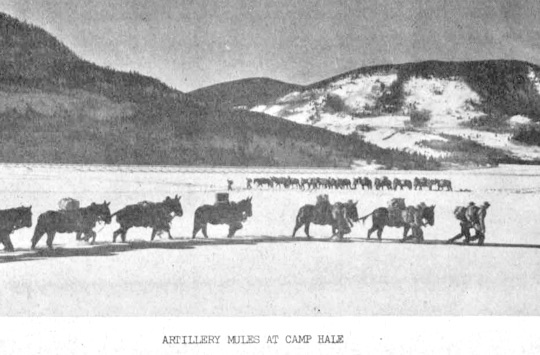

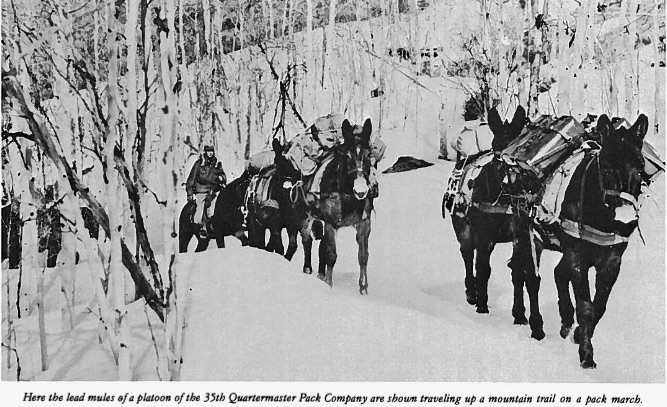

[Lance Blyth] It had a full size headquarters—that’s about 200 personnel officers and noncommissioned officers and enlisted men—to run the place. It had all the supporting units the division would have. It had a signal company—the guys who laid all the wire for the radios. It had a medical battalion. It had a quartermaster battalion, which meant mules. It had four battalions of pack artillery. It also had one of the more interesting units up there: it had a horse mounted cavalry troop, the 10th Reconnaissance Troop, which is a company sized unit. Horse cavalry still actually had a pretty good role to play in during World War II. It just had a huge logistical footprint for an expeditionary army who had to send everything overseas—but you’re gonna activate a unit to train to operate in the mountains with a limited road network, horse mounted calvary did make sense; and so they were sent to Carson and they made the move up in a big convoy in November of 1942.

Strange as it may seem, The 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop would prove pivotal to the division’s training, and to American climbing and skiing after the war. Not only would John McCown become part of the unit; it would eventually absorb the MTC itself—but that’s a matter for our next episode.

The 2,100-person convoy arrived at Camp Hale on November 16—one year and a day after the 87th had been activated at Ft. Lewis. It was quickly followed by the addition of more elements. The 87th’s 3rd Battalion reported for duty on November 18, adding a veteran presence to the camp. Perhaps the most intriguing addition joined the ranks in mid-December, shortly after Colonel Rolfe was promoted to Brigadier General Rolfe. Seven hundred seventy men strong, the 99th Infantry Battalion was a specialized unit of first- and second-generation Norwegian-Americans. Every member had ties to a homeland under Nazi occupation. They would train alongside the mountain troops through the summer of 1943, their animus fueled by letters from relatives enduring life under Hitler’s regime.

But the element at the heart of this episode, and indeed the story of the 10th Mountain Division overall, was the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment. Here’s our advisory board member David Little.

[David Little] In order to reach that 15,000 soldier level, obviously the initial recruitment, the three-letter men that became the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment, were the best of the best. They had three letters of recommendation, they wanted to do this mountain in the winter warfare thing, and that brought in roughly 3,000 to 3,500 soldiers. So the 86th was that next round of recruits.

The 86th had been activated at the end of November, while John and his peers were earning their commissions at Fort Benning, and he’d been assigned to it upon his graduation.

Rolfe’s decision to send experienced mountaineers like John from the 87th to Officer Candidate School and then re-assign them to the 86th upon their return allowed him to seed his new regiment with leadership he trusted.

[David Little] The Army was looking for leadership skills and they were desperate for men that could step forward and make things happen. And John McCown is a great example of somebody that had vision more than just his own ability to, yeah, I can ski and I can climb, but he could help other people do that same thing, and that could be as simple as teaching a guy how to belay or being smart enough to pick the correct line to send a group climbing up a cliff face, and if he could direct the guys, oh my God, this guy has got some command ability and that may have been enough to trigger him going into Officer’s Candidate School and to come back as a second lieutenant because the man could make decisions and he could make them on short notice and at a time when the army desperately needed decision makers.

But because there weren’t enough veterans of the 87th like John to go around, and because all these regiments and companies and platoons required yet more men, Rolfe needed another recruitment push—which is where the National Ski Patrol System comes back into our story.

The mountain troops, astute listeners will recall, had been midwifed by a triumvirate of skiers, climbers, and War Department officials. The man most often credited with the unit’s inception was Minnie Dole, the ascot-wearing, Yale-educated Greenwich insurance salesman who’d helped found the National Ski Patrol System in 1938. While Dole had marched his attention-grabbing campaign all the way to President Roosevelt’s desk, he never could have succeeded without the behind-the-scenes advocacy of the American Alpine Club as well as that of General Harry Twaddle, head of the War Department’s Mobilization Branch, greasing the skids.

The German invasion of Narvik, followed by the Italian debacle in Albania, convinced the Army’s naysayers once and for all. The War Department had activated the test force at Fort Lewis, put Pinkie in command —and contracted Dole’s Ski Patrol to help him fill its ranks.

Like many relationships begun in the throes of impassioned need, the union experienced some interruptions. Dole and company established the now-legendary system that brought in volunteers like John McCown—so-called “three-letter men,” whose trio of recommendations attesting to their skill and character were central to their selection. But once the Ski Patrol had delivered enough recruits to fill the 2nd and 3rd battalions of the 87th—thus meeting their quota—the War Department, which had had mixed emotions about the endeavor from the outset, paused their contract. This, despite the fact that there remained, as Dole would later recall in his memoir, “an enormous gap between the regiment as it stood and the divisional strength to come.”

“To hell with those skiers,” seemed to be the War Department’s response. As the Mountain Training Center was setting up shop at Camp Carson, Army Ground Forces took recruitment into its own hands, directing replacement training centers around the country to review the backgrounds of every new recruit. John Jay recounted the new focus in his history of the unit. “If any man had the following civilian experience,” he wrote, “he was to be sent at once to the Mountain Training Center: mountaineer, north woodsman, trapper, lumberjack, skier, packer, geologist, horseshoer, hunting guide, geographer, saddler and harness maker, teamster, stabler, axeman, prospector, hard-rock miner, and timber cruiser. The emphasis,” Jay continued, “was away from skiing, which had always been regarded with distrust by higher headquarters as a ‘crazy sport.’ Now,” he concluded, “the emphasis was more on the ‘rugged outdoor type.’”

The “rugged outdoor type,” as it turned out, didn’t cut it. Absent the NSPS’s careful vetting process, the men stumbling into Camp Hale via the AGF’s dragnet were, to put it diplomatically, ill suited for the job. Many of them were out of shape, they didn’t like winter and they didn’t like the mountains. “After four months of this,” Jay wrote, “with mounting complaints from the Mountain Training Center about the inferior quality of its new recruits, the Army Ground Forces changed its policy.”

Two weeks before John’s arrival at Camp Hale, the telephone in the National Ski Patrol System’s New York City recruitment office rang. It was Army Ground Forces, inquiring, according to Jay, whether the Ski Patrol could round up two thousand men with winter and mountain experience… in ninety days.

No stranger to hyperbole, Dole remembers the request differently. “I was asked to find 2,500 men in 60 days,” he wrote.

Regardless of the target numbers, the request occurred amidst an increasingly competitive landscape.

According to the War Department’s calculations, winning the war against Hitler required a 4,300% increase in manpower in two short years. Everyone needed men, and the mountain troops were competing with all the Army’s other units for their personnel—hence the parade of reporters and film crews and camera men crawling over the camp when John McCown arrived.

Unlike the Army’s other units, however, the mountain troops were starting at a disadvantage.

At its base in Ft. Lewis, the 87th had operated in semi-secrecy. Washington State fell under the jurisdiction of the Western Defense Command, which had been established on March 17, 1941 to oversee the defense of the U.S. West Coast and parts of the Pacific. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the WDC had implemented a strict news blackout for fear of further Japanese attacks—and the 87th had been subject to the embargo.

As Jay observed, “Their training area [on the flanks of Mt. Rainier], a mere 5,000 feet in altitude, might as well have been 5,000 miles up, so far as any publicity was concerned. Not a single line concerning the mountain troops or their activity was permitted in the national press for several months after war was declared.” For a test force that needed to expand, this was a problem. “All over the United States men of military age were signing up,” Jay continued. “The Navy and the Air Forces were competing to skim off the cream, offering commissions bountifully. Meanwhile the mountain troops, in quiet oblivion, took what was left.”

The unit’s move from Washington to Colorado changed everything. Out from under the Western Defence Command’s blackout, the MTC could finally begin to talk up its efforts—and with the test force slated to become a full division by summer, the marketing push was on.

“Questionnaires poured out of [the National Ski Patrol System’s] New York office to section leaders all over the country,” Jay recounted, “who distributed them to all local members and saw to it that local newspapers printed the details at length.”

“I sent out memoranda to all patrolmen,” Dole wrote, “asking for volunteers. I also went around to the colleges in the east explaining the set up.”

In late 1942, there were fewer than 3,000 ski patrolmen in the country, and while no mention is made of the colleges Dole visited, the number of potential recruits he reached on his campus tours could not have met the new quotas on their own. Dole needed help. Fortunately, he was hardly the only one working overtime to fill the ranks.

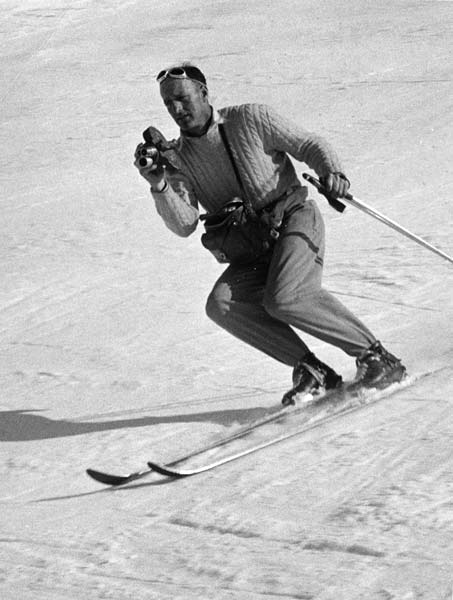

Perhaps the man working hardest was doing so from within the Mountain Training Center itself: the budding filmmaker turned Army photographer, meteorologist, historian, Mountain and Winter Warfare Board gear tester, and general overachiever par excellance, John Jay.

In his history, Jay wrote, “A public relations officer was instructed to prepare news releases to all the major newspapers in the snow and mountain belt of the United States, stressing the rugged training and the need in the Mountain Troops for men with definite mountain experience.” What he didn’t write was that the public relations officer was him.

It’s difficult to think of a person better suited for the job. You’ll remember that Jay had fallen in love with skiing on the eve of its meteoric transformation from spectator sport to national craze, and managed to be in the catbird seat through the seminal moments of its development. In 1934, as the first rope tow in America was coming online at Woodstock, Vermont, and the Boston & Maine Railroad was staving off depression-era bankruptcy by bringing Bostonian office workers to the mountains of New Hampshire and Hannes Schneider’s Alberg technique was sending American hearts into a Teutonic flutter on ski slopes around the country, Jay was documenting it all on the family camera, refining the craft that would go on to make him the father of American ski cinematography. He’d filmed, as he put it, “the Williams [College] Winter Carnival, the Dartmouth Winter Carnival, the second Inferno Race down the Headwall of Tuckerman’s Ravine, and the Madison Square Garden’s Winter Sports Show.” He’d been hired by Time, Inc. to write for The March of Time, a groundbreaking newsreel series that blended journalism, dramatization, and narration to tell the stories behind the headlines. While working as an assistant professor of English at Williams College, he’d applied for, and won, a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, then, while waiting to take the boat over to England, cobbled together Skis over Skoki, a film on powder skiing in the Canadian Rockies. Somehow, he managed to squeeze in a trip to South America’s only ski resort, Farallones, in the Chilean Andes, on the side. By the time he got back to the States, the war was on, which meant the Rhodes scholarship was off, so he put together Ski the Americas, North and South, the first feature-length ski film the world had ever seen, and toured the film instead.

Jay had been hired by the National Ski Association in the winter of 1940 to escort the Chilean ski team, whom he’d befriended on his South American adventure, on an eight-week, 8,000-mile skiing road trip around North America. Unsurprisingly, the trip became the subject of his next film, the 95-minute, Ski Here, Señor, which included famous skiers such as Hannes Schneider and Dartmouth’s ski coach, Walter Prager, expounding on technique. “This picture,” crowed the critics, “is another of the author’s superb skiing films so edited as to furnish entertainment and education for skier and nonskier alike.”

Before Jay could tour the film, though, he found himself in charge of, among other things, PR for the mountain troops at Ft. Lewis. Fortunately for him, he had by then struck up a partnership with a dependable side kick who could tour the film on his behalf. And fortunately for you, dear listener, she was a woman.

We are now fourteen episodes into our sprawling saga, and with the exception of Margaret Smith, the Teton climber who had become the object of John McCown’s fancies as he was learning to climb in Grand Teton National Park, we have not met a single woman who had anything to do with our story. For good reason: there were hardly any women who had anything to do with the mountain troops. We’ll be talking about almost all of them eventually, but only one still bubbles up in the mountain troop history books. Her name is Deborah Bankart, and she was one of the most accomplished skiers of her day.

[David Little] Deborah Bankart in the skiing world—she was one of the glamorous folk.

Born on March 23, 1918, in Lynn, Massachusetts, Bankart had been educated at tony private schools and raised in the limelight of the social pages. She made her first appearance in 1930 with an article announcing her victory in the under-twelve division for children’s horsemanship at the Boston Horse Show. In 1936 her presence at bridge, tea and dinner parties, luncheons at the Ritz Carlton, and debutante balls received coverage no fewer than nine times. Her own debutante ball was announced the next year.

Sports ran in the Bankart family, and she’d begun skiing on the hills behind her grandfather’s estate in 1935, when the pursuit consisted of, as she remarked to a reporter, “simply sticking your toes in and going where the skis went.” It was love at first turn. Upon her graduation from Boston’s prestigious May School in 1936, she embarked for Switzerland’s Geneva College for Women, which complemented its academic offerings with, as Time Magazine put it, “music, art, mountain climbing, skiing and meeting charming young Europeans.”

For most, the college was a finishing school. For Bankart, it was a chance to ski in the Alps. She soon found herself competing on better-than-even terms with her European counterparts—but then Hitler began rattling his sabers, and her parents ordered her home.

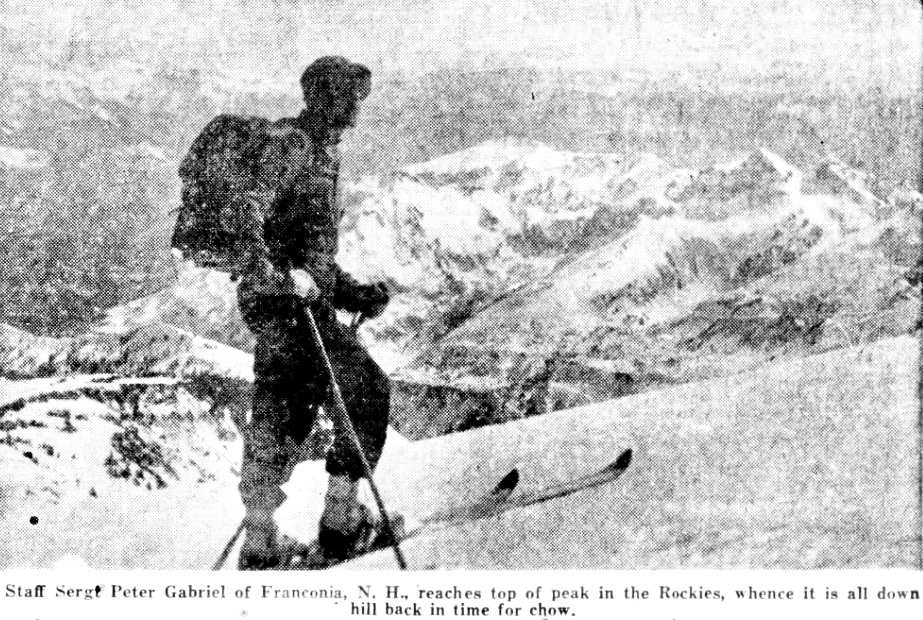

The ski edge, though, was set. By the winter of 1938-39, she’d received her certification as a ski instructor from the Eastern Amateur Ski Association—the third woman in the country to do so—and began teaching at New Hampshire’s Franconia ski school under the direction of future 10th Mountain Division legend Peter Gabriel. The next winter, she became the first female executive director of the Hanover Ski School, a money-making operation tucked inside the town’s Hanover Inn that taught rich kids to ski while their parents schussed the slopes over the Christmas holidays. Home to the alpine skiing powerhouse of Dartmouth College, Hanover was the cradle of American winter sports, and Bankart’s new role put her in close contact with its leading members, including Walter Prager, who was a fellow member of the Hanover Ski School instruction staff—and John Jay.

American skiing at the time remained an insular pursuit. Though it had begun its stratospheric ascent into the popular imagination, its leadership was still the domain of the affluent and the powerful, and the athletic, affable Bankart was at the heart of it all. Trim and lithe, with dimpled cheeks and a toothy smile, she was as charming as she was competent, and as Jay began looking for someone to tour Ski Here, Señor on his behalf, she emerged as the perfect match.

So off she went, “delighting audiences,” as the papers put it, “with her lively presentation” of Jay’s film, which she made in a running commentary, rebellious curls of rambunctious brown hair framing the side of her oval face like Christmas ornaments as she narrated the show. Lowell Thomas, one of the country’s foremost radio personalities, attended the premier. “The audience howled and cheered with delight over the pictures,” he wrote. “It is a show that both skiers and non-skiers will enjoy.”

Part of the film’s allure was Bankart herself, who was, as one paper put it, “Reputed to have a steel-edged Yankee sense of humor which leaves no skier untouched.”

Screenings sold out. Indeed, the film was so well received that the US State Department purchased exclusive rights to the movie so it could show it in South America as part of a goodwill tour. By the time the tour was over, Bankart had screened Ski Here, Señor before an estimated 50,000 viewers on a journey that encompassed some 10,000 miles.

And when it was time for Jay to shift into the propaganda phase of his filmmaking career, he once again turned to Bankart.

Filling Camp Hale with new recruits meant selling the mountain troops to the American public, and film was one of the most powerful ways to do so. While television in 1942 remained largely irrelevant—fewer than 7,000 American households owned a TV set—84 million Americans—more than 60% of the population—went to the movies each week. With a theater in nearly every decent-sized town, film was the beating heart of popular culture, and audiences got their first moving images of World War through newsreels, the short journalistic snippets that played before the main cinematic events. There was perhaps no more powerful way to influence public opinion.

Remember that ascent of Mt. Rainier Jay had made in May of ‘42 alongside an eight-man detachment of the 87th led by Peter Gabriel? And remember those ski films he had put together with Prager and a select crew of the 87th at Sun Valley? Per usual, he’d brought his camera along, and the resulting footage now became the basis for his most important cinematic contribution to date: Ski Patrol, a recruitment film for the mountain troops.

By then, Jay’s reputation as a filmmaker was firmly in the cinematographic firmament, and Bankart’s reputation was nearly as strong. The twenty-five year old socialite-turned-skier had spoken before thousands of people the year before, and with the war as motivation, she picked up where she’d left off, becoming a critical part of the mountain troops’ recruitment campaign in the process.

Bankart debuted Ski Patrol on October 30 with an afternoon showing at Massachusetts’ Berkshire Museum, followed by another later that evening. On Monday, November 2, she screened it at the Hadley School Auditorium in Swampscott, Mass. On November 25, it was on to Rochester, New York, then Buffalo on December 1 and Boston a week later. She screened it before two hundred people at the Drury High School in North Adams, Mass, on January 7, then presented it in the 87th’s old stomping ground of Tacoma, Washington, on the other end of the continent a month later.

The tour’s target demographics were, as Jay put it, “groups of young men who might be potential mountain troopers–ski clubs, schools, colleges, the National Geographic Society.” After each screening, Bankart would cheerily switch hats from narrator to recruitment officer, staffing a desk with application forms for young men in the audience to fill out.

Bankart’s involvement with the mountain troops would continue after the tour as well.

[David Little] After her army recruiting career, she joined the American Red Cross and was assigned to Camp Hale because she knew how to ski and that was the Skiing Center. She worked there for the Red Cross. She also, when 10th Mountain was deployed to Italy, she asked to deploy as well and was deployed to Italy where the 10th Mountain was.

Just as Bankart wasn’t the only recruitment officer hard at work on behalf of the mountain troops, Ski Patrol wasn’t the only recruitment film at the Army’s disposal. The newsreel crews running around Camp Hale when John McCown arrived were part of the process as well. “The most ambitious and far-reaching publicity,” Jay noted, “was a full-length technicolor film by Warner Brothers, photographed at Camp Hale during five busy weeks in the winter of 1943. Released under the title, ‘Mountain Fighters’ it attracted many good recruits to the ranks.” Between Ski Patrol and Mountain Fighters, Jay estimated that more than seventy-five thousand people saw the mountain troops in action during 1943, making Camp Hale one of the most publicized camps in the nation—and, he continued, “many of [the young men in the audiences] immediately filled out the NSPS application blanks which were distributed after each performance.”

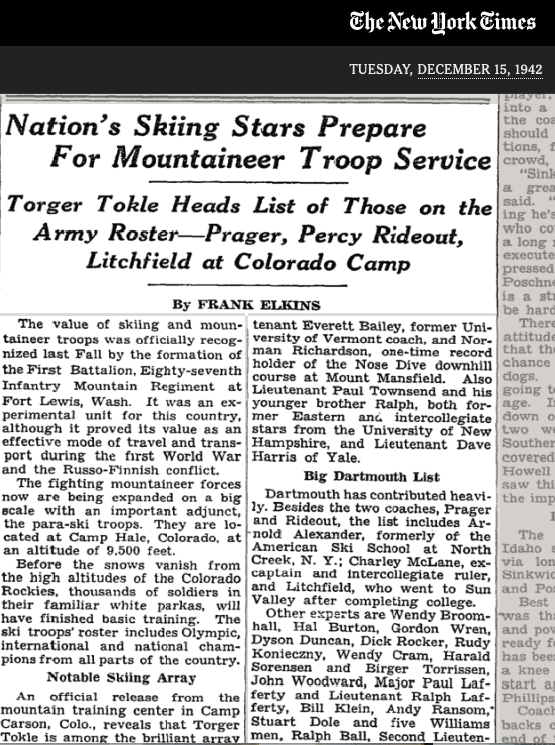

As powerful a medium as film might have been, there were others at Jay’s disposal as well. On December 15, 1942, The New York Times, which had a daily circulation of half a million readers, published an article by its ski correspondent Frank Elkins entitled, “Nation’s Skiing Stars Prepare For Mountaineer Troop Service.” The article, which highlighted the enlistment of well-known racers and mountaineers like Prager and world-famous Norwegian ski jumper Torger Tokle, framed it as a national call to duty.

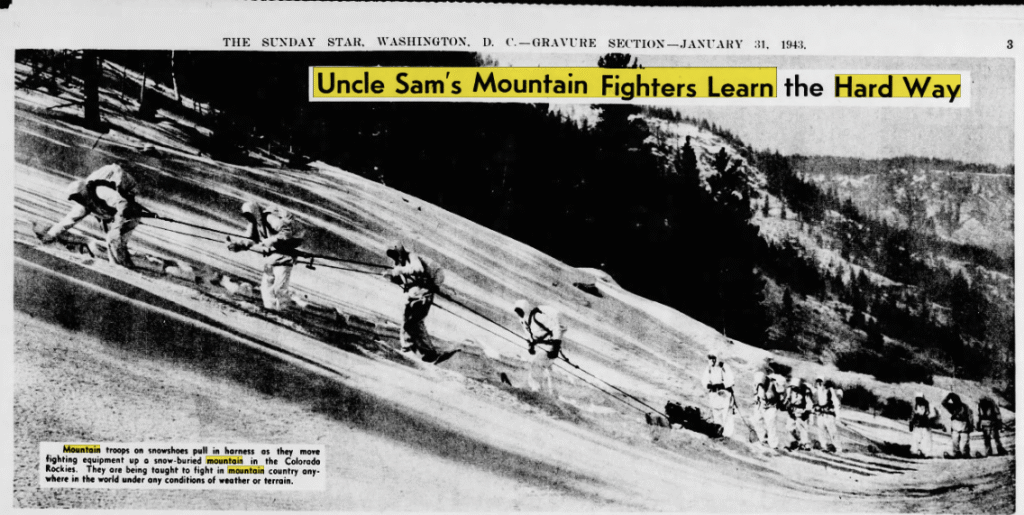

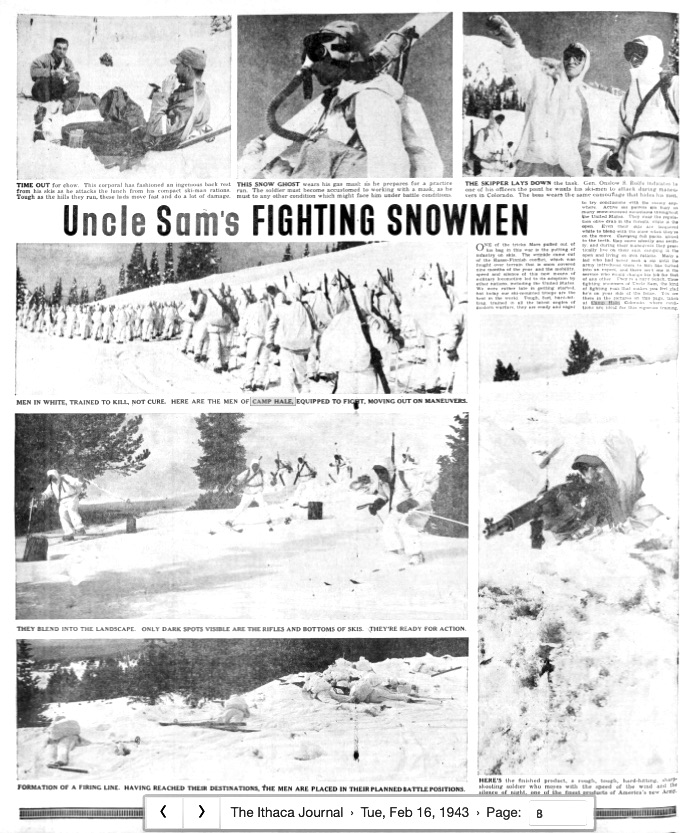

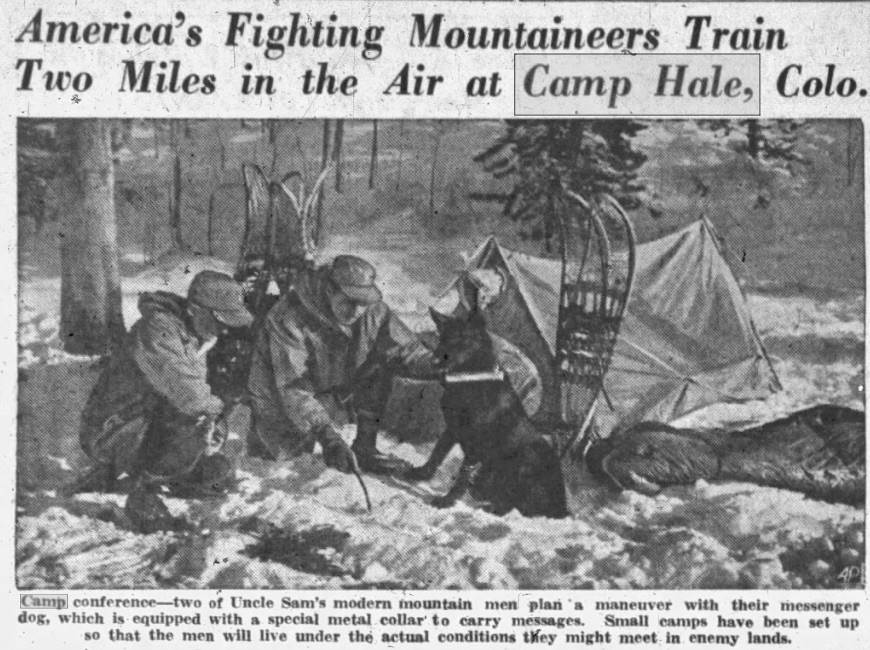

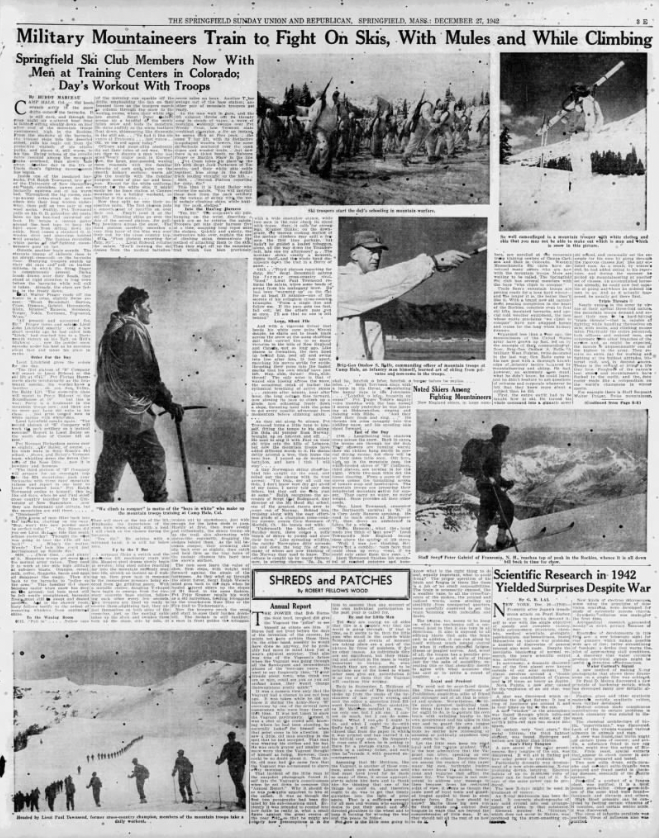

Others quickly picked up the rallying cry, and soon it seemed you couldn’t open a paper in America without reading about Camp Hale and its soldiers. There they were, in Tennessee’s Knoxville Journal on January 17, under the headline “US Trains First Mountain Troops in Zero [Degree] Weather.” “Mountain Troops Get Montanans,” announced the Montana Standard, 2,000 miles away. “Uncle Sam’s Mountain Fighters Learn the Hard Way,” crowed Washington DC’s Evening Star. “Mountain Artillery Troops Are Tough,” chimed in The Philadelphia Inquirer the same day.

“Camp Hale, Colorado,” began Buddy Marceau’s four-page article in The Springfield Sunday Union and Republican. “Ski boots crunch softly in the snow drifts outside the barracks. It is still dark, and through the crisp night air scattered hoar frost is falling, sifting silently down on roof after roof of the mountain troops contonment, high in the Rockies. From the shadow of the barracks, the trooper steps into the deserted street, pulls his bugle out from the protective warmth of his alpaca parka, and places it, still warm, to his lips. Dying echoes of the reveille notes resound among the mountain peaks overhead, then slowly fade away. Another day in the life of uncle Sam’s fighting mountaineers has begun.”

Journalists like Marceau had an inside man, and his name was John Jay. In fact, Marceau hadn’t written the article in The Springfield Daily Republican; Jay had. As he sent out his press releases to media outlets around the country, the papers republished them, applying pen names to cover up the fact that they were American military propaganda.

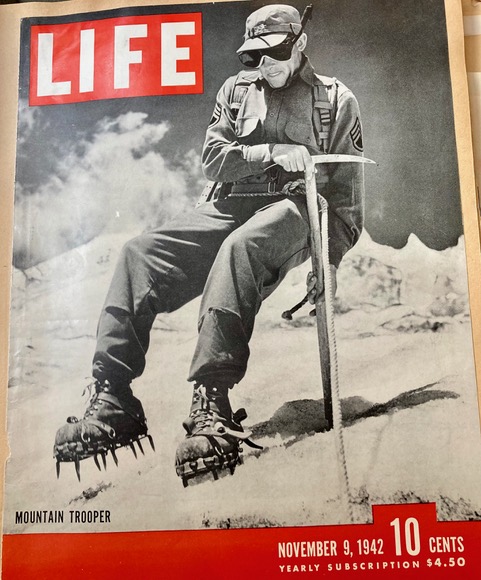

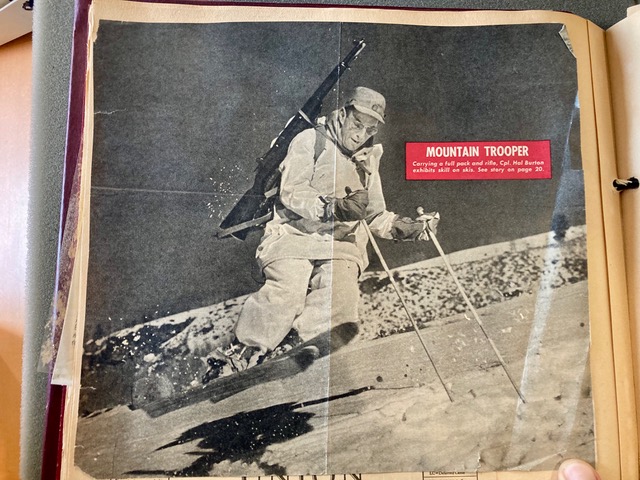

Magazines, too, leaned in. LIFE, with an average weekly circulation of 3 million, had featured a black and white photo of “US Ski Trooper” Sergeant Reese McKindley on its January 20, 1941 cover. It followed this up twenty-two months later with its November 9, 1942 cover, featuring “Mountain Trooper” Sergeant Walter Prager descending the glaciated slopes of Mt. Rainier, tongue protruding between perched lips with the effort.

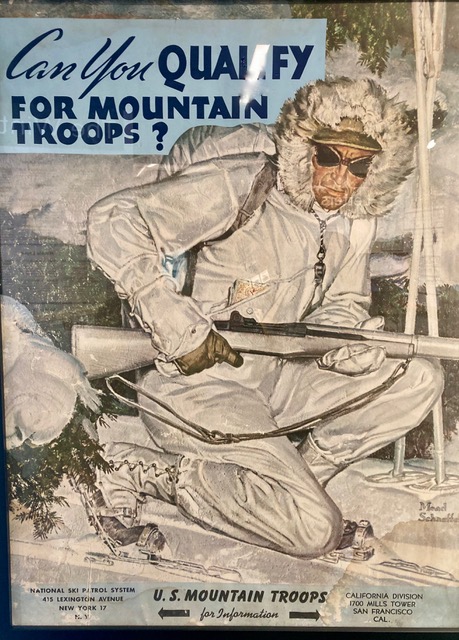

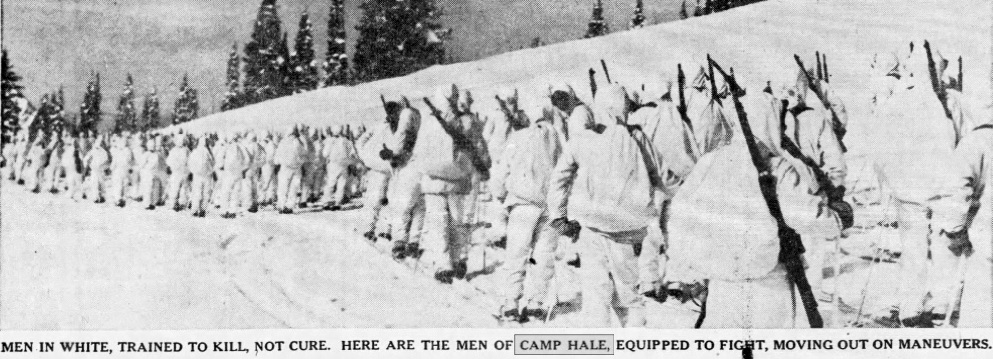

On March 27, well-known illustrator Mead Schaeffer landed the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, circulation 3.5 to 4 million, with his rendition of a mountain trooper. Crouching over his skis amidst snow-covered pine boughs, his rifle cradled in his hands, the soldier looks directly at the reader from behind jet-black glacier glasses. He is clad head to foot in white –white overboots, white pants, white ski parka with white fur-lined hood, a white cover draped over the top of his pack, white bamboo ski poles, white skis. He wears a white mitten on one hand and a glove with a trigger finger on the other. Even the bindings on his skis are white. Apart from his dark glasses, the only thing that isn’t white is his face, bronzed tan by the sun. Rugged, capable, ready to fight in all weather and all conditions: if America needed heroes, the mountain troops were it. The Army bought a thousand copies of the issue to use as recruiting posters.

Of all the mediums at Jay’s disposal, though, none could match radio for reach. More than 80% of American households owned one, and the average family listened for 3 to 4 hours per day. The news program Lowell Thomas and the News was heard by some ten million people every evening. On October 13, 1942, Lowell Thomas shared the story of the ascent of Mt. McKinley, as Denali was then known, by Bradford Washburn, Bob Bates, Albert Jackman and other members of the Quartermaster Corps as they tested equipment for the Army’s new mountain troops. His audience included not only civilians but also military personnel and decision-makers in Washington. When, on January 17, Camp Hale made its radio debut to the nation on the war program the Army Hour, three million Americans tuned in to listen. By the time the Columbia Broadcasting System’s coast-to-coast radio program Vox Pop reported on the mountain troops six months later to some 23,000,000 listeners, the unit had become a staple of the American public’s imagination.

Skiing adjacent organizations such as the American Alpine Club, US Forest Service and National Park Service assisted too, placing notices in their respective publications. As the lightbulbs popped and the microphones crackled, John McCown and his comrades helped elevate the mountain troops into a patriotic narrative, legitimizing the test force as they sold the public on the need for a specialized unit. Before long, Jay observed, “The average American citizen seemed far more interested in the “ski troops,” as they were popularly but incorrectly known, than was the War Department.”

The media coverage was the mouth of the Army’s recruitment funnel. Its spout was The National Ski Patrol System’s office in Room 222 of New York City’s Graybar Building. By the time John McCown arrived in camp, Jay’s public relations efforts, Deborah Bankart’s film tour and the National Ski Patrol Systems’ latest push were achieving their desired effect. Soon, Jay observed, “the filled-out mountain troop applications were coming back into the NSPS office. Those approved were passed on through cleared channels into The Adjutant General’s Office in Washington and thence to the applicant’s future reception center. Approved applicants were in Camp Hale in ten days from the time they first filled out their applications.”

Unlike Army Ground Forces’ recruits, the young men pouring into the 86th Mountain Regiment proved to be, as Jay put it, “excellent mountain troop material.” “Not only were these men skilled in the ways of skiing and the mountains, which in itself cut down the training time by one-half, but they were smart, keen, [and] enthusiastic [about] a job they had picked out for themselves.”

The influx had a secondary effect as well. Morale, which had been ravaged by high altitude, pollution, and social isolation when Camp Hale opened, began to improve. “As handpicked men—high school stars, college men, all young men of far-above-average abilities—began to flow into its ranks,” Jay wrote, “an esprit du corps quickly grew up in the 86th, much as had grown the year before in the 87th…. The highest morale in Camp Hale was that found in the 86th Infantry.”

Perhaps predictably, Dole, a salesman by trade, took a bow. “We had 3,500 men enlisted in 60 days,” he wrote in his memoir. Regardless of who deserved the credit, the caliber of the men flowing through the gates was beyond dispute. An intelligence rating of the various units comprising the Mountain Training Center revealed that two out of every three men in the 86th who had arrived at Camp Hale via the NSPS’s spout were potential officers; the third was a potential noncommissioned officer. By comparison, 38% percent of the 10th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop were below the medium intelligence level of the entire army.

As Lance Blyth points out, the success of the winter recruitment push would have long-term implications for Army Ground Forces and its recruitment contract with the National Ski Patrol System.

[Lance Blyth] The Army kind of learned from experiences in the fall of ‘42[that] it’s harder to find these people than you think. Minnie Dole’s National Ski Patrol had continually done a good job of bringing in quality personnel, as had the American Alpine Club. So their experiences were actually relatively positive. The army reestablishes the contract in the fall, but then at that point it never goes away. They keep it going till 1944. Lesson learned for the Army: they knew they needed outside assistance

While the 86th was ramping up, more veterans from the 87th were rolling in. You’ll recall that the 3rd battalion of the 87th had arrived at Camp Hale in November, shortly after the Mountain Training Center took up residence. The 1st and 2nd Battalions, meanwhile, had been sent to California.

[Sepp Scanlin] The Army is at this point beginning to think about expanding their horizons. They had not really been able to do true force-on-force training, so they hadn’t really done field problems that tested their tactical expertise. They’d done a lot of development of tactics and techniques in the mountains where they tried to develop that themselves, but they hadn’t gone through and tested themselves against what we would call a free-thinking enemy. So they actually send them to Camp Jolan, California, [where] they were pitted against some Filipino Americans and some other units that are there as opposing forces. So this is very much like what is going on in the rest of the army [like] the Louisiana Maneuvers [and] all the other exercises that they’re doing force on force. Ssually it was blue and yellow and green teams competing against each other. Where they’re refereed, there’s umpires and they literally have to conduct tactical exercises against somebody who is trained similarly and can think on their feet. I believe some of this is going on because they’re already beginning to think about maybe that they’re going into the Aleutians campaign.

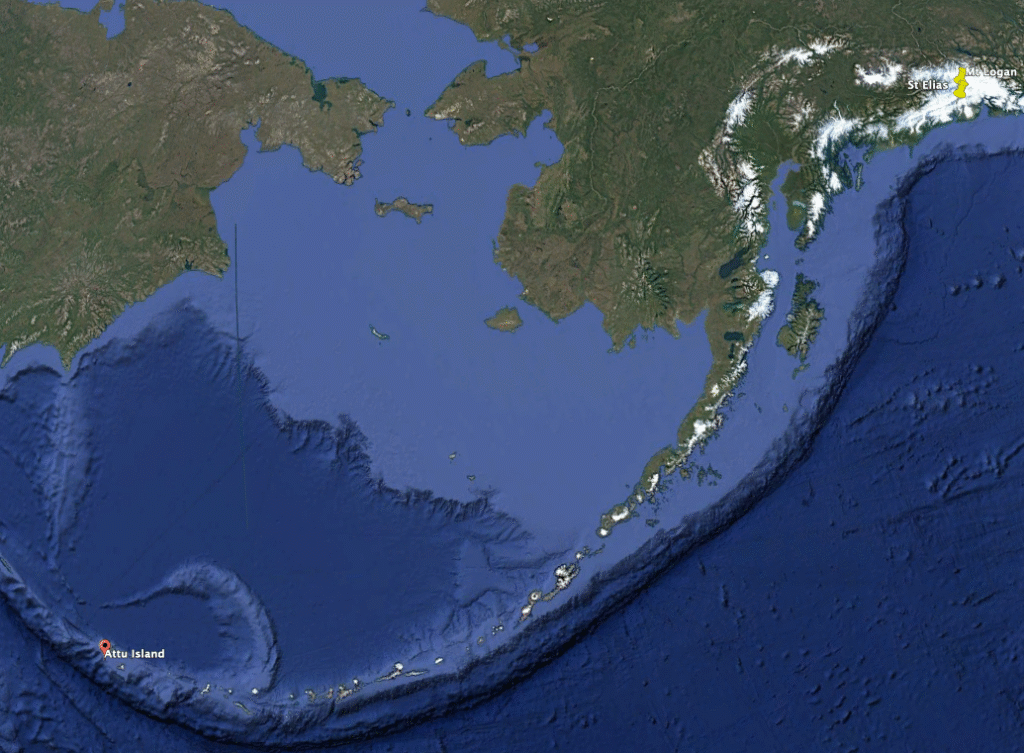

Shaped by the intense geological forces of the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Aleutian Islands are a slender, fractured archipelago of volcanic landforms that arc westward 1,200 miles from southwest Alaska into the vastness of the North Pacific Ocean. Their steep volcanic peaks, battered by constant storms, dense fog, and frigid winds, are home to some of the worst weather on Earth.

In June 1942, while launching their offensive at Midway, Japanese forces bombed Dutch Harbor and invaded the islands of Attu and Kiska, capturing a small U.S. Navy weather detachment and seizing American soil for the first time since the War of 1812. Though strategically limited, the invasion’s psychological impact on the country was profound. Over the following winter, the Japanese fortified the islands while the U.S. Navy sought to isolate them, leading to sporadic battles at sea and repeated air raids hampered by relentless weather.

U.S. forces would land on Attu in May 1943, encountering fanatical Japanese resistance. The greater enemy, though, would prove to be the Aleutians themselves. One-hundred-twenty-mile-per-hour winds, dense fog, freezing temperatures, and near-constant rain and snow would expose a critical gap in U.S. military preparedness for mountain and cold-weather warfare. Determined not to repeat the disaster, the Army would tap the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment for the next phase of the battle—a subject we will cover in its entirety in one of our next episodes.

Fresh off their California maneuvers, the 87th’s 1st and 2nd Battalions arrived at Camp Hale at the end of the year—an event detailed in Donald Traynor’s self-published, two volume memoir, The Last Ski Troopers.

Traynor’s fame would eventually be cemented by the full-size statue of a mountain trooper he helped conceive that now sits prominently in the center of Vail, Colorado. Had his memoir been his only legacy, far fewer people would recognize his name. I don’t know whether to refer to it as a war memoir or a self-congratulatory piece of pornography that wraps itself in the cloaks of war to justify its own tawdry existence, but I will say that I’ve read it so that you don’t have to. By the time Traynor—who, for whatever reason, takes on the nom de guerre Steve Lyman in the books—gets to his arrival at Camp Hale with the 87th’s E Company, he has already recounted, in lurid detail, sexual escapades with no fewer than four women. He could have more accurately entitled his biography Fifty Shades of Olive Drab.

Traynor presents their arrival with characteristic flourish. After days of travel, the train had pulled into the Pando station on the eve of the new year and discharged its passengers to the night. As Traynor, or Lyman, marched along with 900 of his fellow troopers, the silence interrupted only by the crunch of boots on the hardpack snow, he marveled at the mountains looming all around him—and found himself quickly overcome with emotion.

“I could not contain myself,” he wrote. “Suddenly, with little thought of the consequences, I started to sing.”

Spontaneous outbursts of song in the midst of a march are generally frowned upon in the Army, but Traynor couldn’t resist. Congratulating himself on his abilities (“Fortunately,” as he observed, “I had a good voice”), he began belting out the lines from Ninety Pounds of Rucksack in his “clear, deep baritone.”

“Once the chorus came in,” he wrote, “the entire rifle company of 210 men joined in. Shortly after, the complete battalion of over 900 men was singing along. The sound was staggering in the quiet camp. The 87th was coming home and we wanted everyone to know it.”

As Traynor, or Lyman, continued to transfix the entirety of Camp Hale with his melifluous voice, more and more soldiers joined in. “By the time the song and the yodeling came to an end,” he wrote, “the entire regiment of over 3000 men were roaring Ninety Pounds of Rucksack at the top of our lungs. Any of the cadres in the Camp came to the windows of their barracks to listen and watch. It was a thrilling moment for every man within sound of the voices. The 87th mountain regiment was home and we wanted everyone to know it…. I had never been prouder in my life.”

Having not been there myself, I can neither confirm nor refute Traynor’s depiction of E Company’s arrival at Camp Hale, but it did occur at an opportune time. General Rolfe needed experienced men, and at long last they were beginning to march through the gates.

The 87th’s arrival, coupled with the recruitment efforts to fill out the ranks of the 86th, was moving the expansion in the right direction. But as Lance Blyth observes, for every step General Rolfe took forward, the Army itself seemed intent on dragging the effort half a step back.

[Lance Blyth] The Army is continually transferring what they call fillers in. These are men who were recruited one place, gone through their basic training and can come and be basically… fill in a unit. If you’re missing a hundred people, they’ll send you a hundred people. So the 87th Mountain Infantry gets there. It finds the 86th is forming up. To stand that unit up, to begin training it—’cause these are all volunteers;they had not been through basic training or anything—they have to take men out of the 87th Mountain Infantry. They have to take their most experienced, maybe a third to a half or what have you, to get the 86th up to full speed and get it training.

So fillers come in January of 1943. The majority of them came into the 87th as a backfill, and most of them were men who had transferred, who had been part of the 30th and 31st, and I think 32nd infantry divisions that had been mobilized and had been training down in the Mississippi Delta. And these men were rapidly called flatlanders by the volunteers. So you have this interesting mix you will have at Hale through its entire existence. There’s a good chunk of people who want to be there. There’s a larger chunk of people who did not ask to be there, were sent there. Many of them adapt, but there’s always a group that doesn’t want to be there, never adapts, and they don’t know anything about the mountains, about the cold. And they’re walking into Leadville, Colorado in January and February—not the most kind climatic place.

I asked Sepp Scanlin to help us understand the dichotomy between those who wanted to be at Camp Hale and those who did not— and the impact it had on the expansion.

[Christian Beckwith] And so, you know, you’ve got the people like McCown and Charles McLane and some of these others who are very much mountain people before this whole mad experiment even begins. But they’re the 20% and then the 80% of the people at Camp Hale, they’re not coming from a love of mountains. They’re just ending up there. What was it like for them?

[Sepp Scanlin] Well, I mean, some were absolutely miserable, and I think that’s really indicative of the challenge that General Rolfe has, right? Like at one point the Army assigns an entire swath of essentially California Pacific Islanders to come into the division because it’s a manpower decision. Like you need a bunch of troops, here’s a bunch of troops, we’re gonna send them to Colorado. This is not their environment. Like, they do not want anything to do with it. Add in, as you well know, that not everybody can adapt to altitude, right? Like, there’re physical limitations.

The most notorious thing at Camp Hale is the Pando hack, which is a combination of the soot and the smog that is created by the creation of this camp and all the trains that are passing through that are settling in this valley. So the camp itself essentially becomes covered in smog. Add into that, that you are at essentially 10,000 feet and almost everybody gets a level of pneumonia or bronchial infections that some of them never recover from. They actually have to be sent down to Denver to recover, and they’re not able to come back to the division. They can’t function at that altitude.

So there’s this constant churn of personnel that is impacting the unit’s ability to train. It’s absolutely impacting Onslow Rolfe’s ability to field this unit that he’s been tasked to do. But imagine poor people like John McCown who now have this training task that they get these new troops, he’s gonna get his new platoon, and next thing you know is a third of them are in the infirmary with bronchial infections. So he spends time training it. Well they’re gonna come back, so he’s now training 10 more people, right? So it’s this never-ending cycle of trying to catch up a basic level of soldier capabilities from the level of a brand new lieutenant like John McCown all the way up to General Rolfe who’s trying to do this for the entire 15,000 troops that are now occupying this, and he’s probably cycling out 20% of his troops every month just because they’re not able to maintain this at the altitude and with the environment that they’re operating in.

It was thus, as John Jay pointed out, “a curious mixture that made up the Mountain Troops. There was no middle group. Men either loved the life of a mountain trooper and strove hard to perfect themselves in its difficult skills, or hated the entire setup violently and took no interest in the training whatsoever. These latter would point out, vehemently, that they hadn’t asked to be mountain troopers and they directed all their talents towards effecting a change to some more pleasant and less arduous assignment.”

Training

The success of the so-called test force under Rolfe’s command depended on its training. That, in turn, depended on his ability to provide not one but two sets of instruction: the Army’s basic training; and the specialized training necessary to execute maneuvers in cold weather and mountainous terrain.

The Army’s assembly line was set up to provide the former at replacement or infantry training centers across the U.S., typically in places where weather didn’t interfere with the process. It was also set up to work in batches: put 200 to 1,000 troops through basic training at a time, send them out to their divisions, and start again on the next batch.

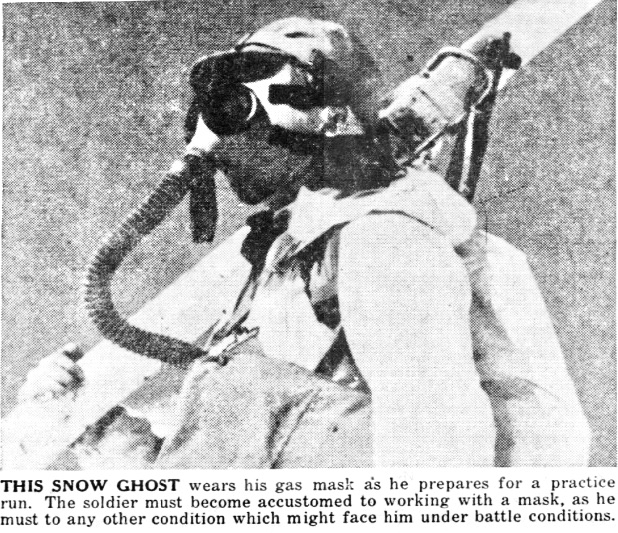

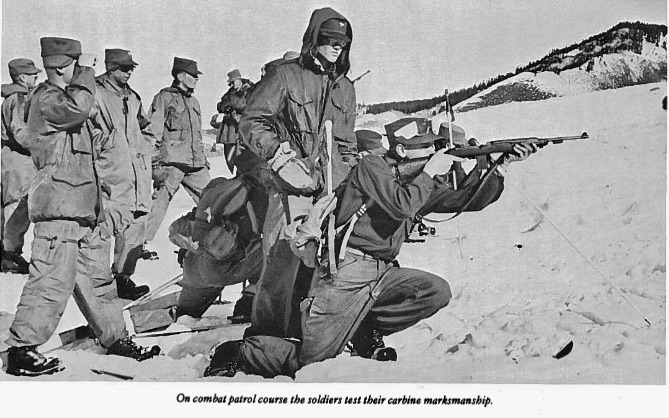

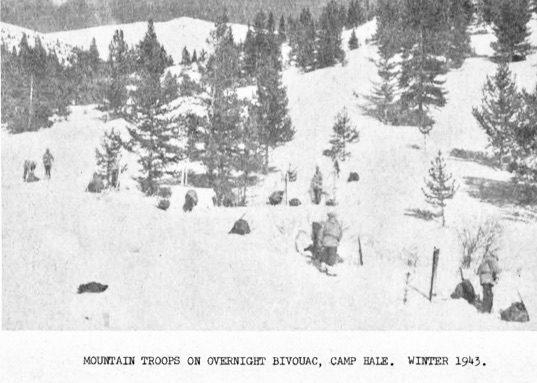

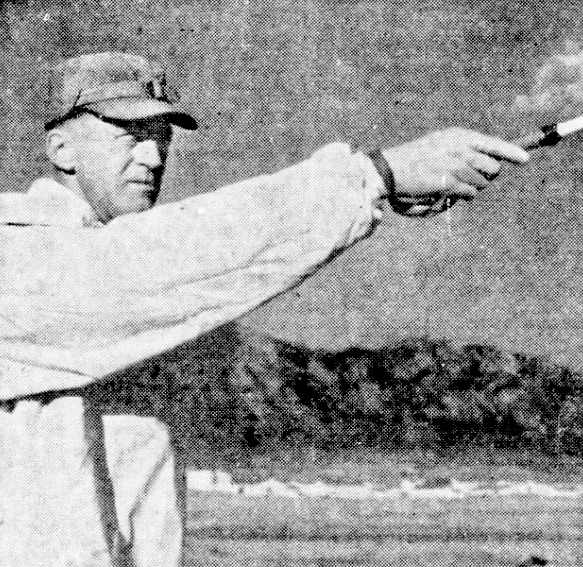

None of that was happening at Camp Hale. Many of the new recruits had had no training at all, forcing Rolfe and his instructors to whip them into shape piecemeal, on an ongoing basis, as they showed up. Calisthenics, obstacle courses, marches, military discipline and customs, close order drills, formation marching, rifle marksmanship, bayonet training, first aid, hygiene, gas mask and chemical warfare drills, foxhole digging, the camouflaging of positions and various other elements of fieldcraft all had to be taught—and, as John McCown was getting settled at Camp Hale in early 1943, that meant teaching it at altitude amidst blizzards and subzero temps.

What Rolfe and his instructors would eventually come to realize, but didn’t yet know, was that you couldn’t teach basic training and specialized training at the same time. In order for a new soldier to master live-fire exercises at Camp Hale, he had to know about frostbite or he’d risk losing his fingers to the cold while learning to shoot. If you wanted him to conduct maneuvers in the snow, you had to teach him about cold-weather layering so he didn’t get hypothermia. You couldn’t send men on mountain patrols without teaching them about avalanches, which meant teaching them about meteorology, rescues and evacuations as well. And—designed as it was for flatland, warm-weather fighting—none of it was in the Army Ground Forces’ basic training playbook.

As our advisory board member Lance Blyth notes in his book, Ski Train Fight, “Any winter training event in the mountains took several times longer” than the Army anticipated in its usual directives. “Acclimatization and cold weather complicated basic training. Standard plans called for movement to training areas via motorized vehicles, which the [Mountain Training Center] did not possess, thus adding three hours a day. Bivouacking at the training area would save time, but this required men acclimated and trained in cold weather camping….” Ultimately, the MTC would determine that specialized mountain instruction added four weeks to the thirteen weeks Army Ground Forces typically allotted for basic training.

You gotta feel for Rolfe. Absent specialized personnel, AGF had sent him officers from bases in the south to make up the nucleus of the MTC. As recruits continued to arrive in Pando unacclimatized and physically unfit, they were issued skis and climbing skins and ski boots and gaiters and sleeping bags and mountain tents by these Old Army Regulars who didn’t know how to use such equipment themselves. But while Rolfe lacked a functional manual he could use for basic training in the mountains, he did have one for parts of the specialized instruction—and it had been written by some of the best in the business.

The previous winter, Lieutenant Johnny Woodward, with the input of world-class mountaineers such as Prager and Gabriel, had taught the 87th to execute their maneuvers on the flanks of Mt. Rainier. Two handbooks, the publication of which had been expedited to assist the Army in standing up its mountain unit, had helped guide their work: David Brower’s Manual of Ski Mountaineering, and Ken Henderson’s Handbook of American Mountaineering.

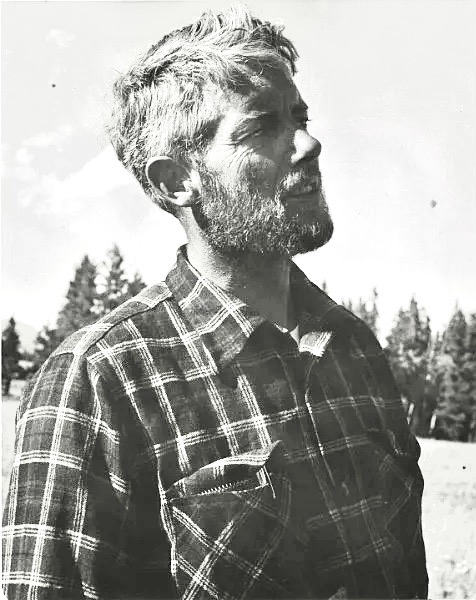

“From these books,” Jay wrote, “and from the rough notes and data that were compiled during the winter of 1942 on Mt. Rainier,” two privates, working under Woodward’s direction, had begun developing a field manual that could be used to instruct the troops. One of them was Private Stuart Dole, a ski jumper from UC Berkeley. The other was Brower himself.

In addition to his experiences editing the Manual of Ski Mountaineering, Brower had learned the ropes, as it were, with the Rock Climbing Section of the Sierra Club in the mid-1930s, and then applied his lessons to the first ascent of the volcanic desert behemoth Shiprock as well as countless new routes in the Sierra Nevada. He’d enlisted in the Army on October 9, 1942, and over the course of several months, first at Camp Carson and then at Camp Hale, he and Private Dole applied their expertise to, as Jay put it, “chapters on organizational equipment, mountain rations, mountain marches, avalanches, military skiing, first aid in the mountains, transportation of casualties in mountain country, mountain medicine, mountain weather, and aneroid barometer.”

Under pressure to expand as quickly as possible, the Mountain Training Center had submitted several of the chapters to Army Ground Forces for approval in September 1942. Because this is the Army we’re talking about, AGF responded by asking who had authorized the MTC to write them in the first place.

“Somewhat taken aback,” Jay wrote, “the Mountain Training Center searched its files and replied … that their directive had its origin in a War Department letter of [November 15, 1941]” that established the test force in the first place. “Army Ground Forces said no more on the subject,” he continued, “and work on the manual was resumed.”

The fieldbook, which would come to be known as the Proposed Manual for Mountain Troops, would never receive official authorization, leaving General Rolfe and his instructors without a sanctioned way to teach the troops. But as we’ve discussed, progress in the Army often occurs in the gray areas between approval and prohibition — and with or without sanction, the manual was the only playbook they had.

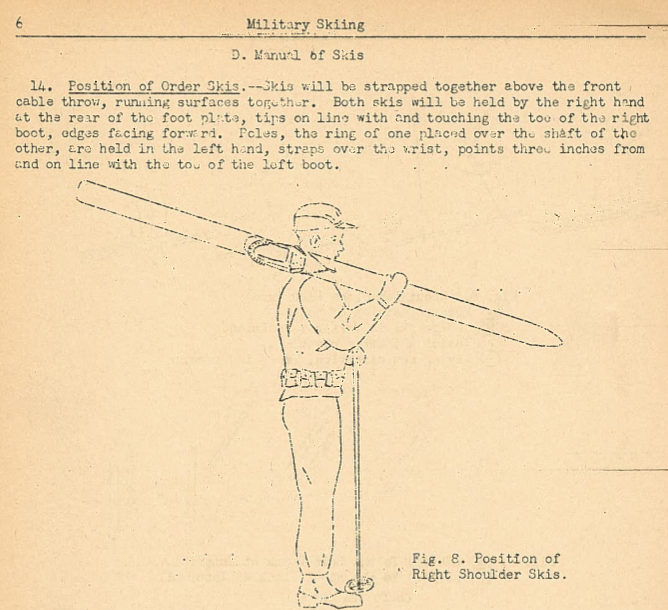

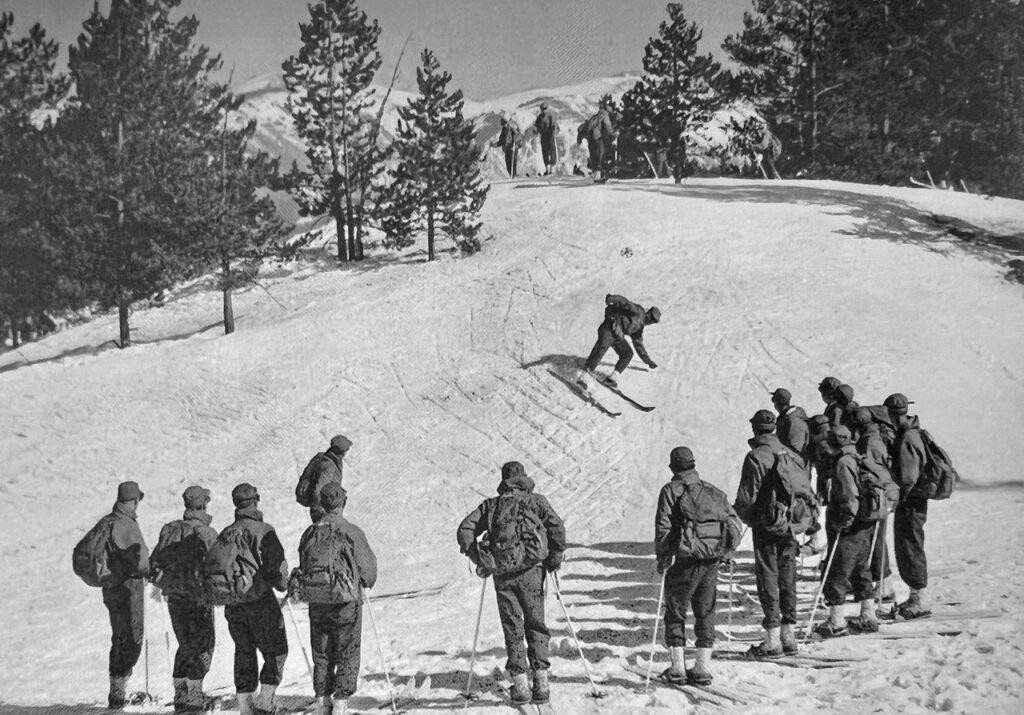

And, to be honest, it was pretty damn good. Take chapter XI, for example, on Military Skiing. Not everyone at Camp Hale had to learn how to ski, but for those who did, the chapter distilled everything Brower, Stuart and the 87th had learned on the topic into thirty-five concise, tidy pages instructors could use to bring even flatlanders up to speed. Complete with illustrations, it covered a full spectrum of skills, from falling to getting back up to skiing with a pack and rifle.

As the chapter’s introduction put it, the course was “designed to give the instruction needed to enable a soldier who has not skied before to travel safely, with a pack and in a unit of men, over rugged, snow-covered mountain terrain.”

Civilian skiing is skiing downhill, a diversion enjoyed between the hours of nine and four on lift-serviced slopes. Army skiing is a tool, one that allows units of men to successfully execute multi-day cross-country missions efficiently and autonomously. Though the chapter included the fundamentals of civilian skiing, it placed its greatest emphasis on Army skiing. This included the Manual of Skis.

Ask any GI in the US Army in World War II how he carried his rifle and he will refer you to the Manual of Arms, a set of instructions on how to handle, use and maintain his weapon. Ask any modern-day skier to name the greatest hazard at a busy resort and she might tell you it’s decapitation by whirling as the beginning skier, skis perched atop a shoulder, turns unexpectedly to retrieve his young daughter’s ski poles. Now imagine hundreds of skiers whirling at random and you can see why, at Camp Hale, ski etiquette was a crucial part of the program.

The Manual of Skis, as the etiquette was called, illustrated how to stand at attention with skis, how to carry them, how to lift them onto one’s shoulder without whacking the next in line, and how to coordinate one’s movements as a unit. If ski areas today implemented a similar protocol, the world of resort skiing would be a much safer, and a much more civilized place, as a result.

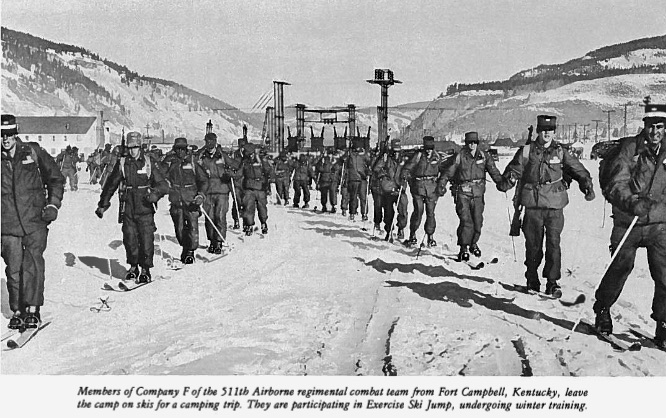

As I mentioned, not everyone at Camp Hale had to learn to ski. The infantry regiments did, of course, for they were the front lines of the unit’s engagement with the enemy. So did the signal company, as they were responsible for stringing communication lines across all sorts of terrain in winter as well as summer. Ten percent of the supporting units—artillery, ordnance, military police—received ski training as well. “The rest,” Jay wrote, “got snowshoe instruction and practical experience in living in the snow, both above and below timber.”

The training took place, as Blyth points out in his book, on Cooper Hill and “one of four slopes, lettered A, B, C and D, around Camp Hale, each with a five-hundred-foot rope tow….” A, B, C and D were the bunny slopes. Cooper Hill, which featured a 7,000-foot-long rope tow, the longest in the country, was the camp’s elementary school, with long, gently angled runs perfect for neophyte skiers to master the essentials. Seventy teachers and 20 officers made up the instructor cadre; each one had eight to ten students and ten days to teach them how to ski the army way—which is to say, with heavier and heavier packs. Students began with rucksacks weighing ten pounds and then added ten pounds per each ten-day block until they were skiing with packs that weighed forty pounds, not counting their rifles. The instruction itself entailed everything from “cross country hikes in deep powder snow” to “downhill [turns] on packed or powdery slopes….”

There was, as the former newspaper man and future author of The Ski Troops Hal Burton conceded in an article in the Ski-Zette, “much more snowplowing and stem turning than the more heard-of stem Christies”—but all of it, he pointed out, was done under the tutelage of some of the country’s finest skiers. Lieutenant Harold Link, a competitive ski racer and mountaineer from Seattle, was in charge of the detachment, while Sergeant Gabriel ran the ski school. Any arguments over techniques were adjudicated by, as Burton put it, “the first skiing officer in the American army,” Captain John B. Woodward.

Effective movement in the mountains cannot be learned on packed slopes served by ski lifts—something Rolfe and his instructors would come to learn later. Similar insights would emerge over time: travel on skis and snowshoes occurs at different rates of speed, which creates problems on longer marches; training in controlled environments does little to prepare troops for exercises in wilder terrain; proper instruction can only be provided by those with both mountain and military expertise.

But these insights were still to come. As the winter of 1943 settled in, A, B, C and D slopes, Cooper Hill, and the wisdom contained between the covers of The Proposed Manual for Mountain Troops was better than the alternative, which was nothing at all.

Special training missions

As devoted listeners of this podcast know, the impact of what would become the 10th Mountain Division extended far beyond Camp Hale. David Brower and Ken Henderson’s handbooks distilled previously rarified expertise into a distinctly American form of institutional knowledge. While they proved critical to the mountain troops’ instruction, their lasting value came afterward, when they became how-to guides for a generation of mountaineers. In outfitting the soldiers with the materiel they needed to conduct their alpine manoevers, Bob Bates, Bill House, Bestor Robinson and the mountaineers in the Quartermaster General’s office established the foundations for both a customer and manufacturing base for the postwar outdoor recreation industry.

But the 10th’s full influence on American culture might never have materialized without its special training missions. Born of necessity, these exercises—featuring highly trained instructors like John McCown—were more than just strategic moves in the War Department’s chess match against Hitler and the Axis powers. By transferring mountain expertise from the playgrounds of the wealthy to the training fields of American GIs, they helped democratize the outdoors itself.

We’ve detailed a few of them already. The two-week ascent of Mt. Rainier in May 1942, followed almost immediately by the test expedition to Alaska that successfully made the third ascent of Denali, North America’s highest peak, had been critical to the Quartermaster General’s efforts to successfully test the mountain troops’ new toys. Inspired by the observation that it’s easier to watch a movie than it is to read a book, then-Lieutenant Johnny Woodward’s two cinematic missions to Sun Valley transfered the sum total of the Army’s understanding of military skiing to the medium of film. The results allowed Rolfe and his instructors to familiarize new recruits with the fundamentals of the pursuit in screening rooms before they took the field.

A mission in June 1942 to the Olympic Mountains of Washington State determined that horses were more a liability than an asset in rugged terrain. Yet another, to Aspen, Colorado, in the fall was tasked with figuring out how to build aerial tramways and suspension bridges in the mountains. Though the mission itself was successful—and would go on to pay dividends when the 10th was deployed to Italy—its finale was not. With all 700 townspeople in attendance and a brass band in tow, the detachment set off on a triumphant cross-country march to the newly built Camp Hale—only to return sheepishly the next day, their journey home having been thwarted by thirty-foot snowdrifts and recalcitrant mules.

While the engineers were building their bridges, another mission was underway to the north—complete with an origin story surreal enough to have been cooked up by Hollywood itself. The Columbia Icefield Expedition, as the endeavor would come to be known, began in July 1942, when fifty men and three officers embarked from Ft. Lewis. Not that any of them knew where they were going: the entire project was cloaked in robes of secrecy to preserve the element of surprise.

Hitler’s invasion of Norway in April 1940 had done more than simply underscore the need for American troops who could fight in the alpine. It had also given him control of the Vemork hydroelectric plant in southeastern Norway. Surrounded by a rugged coastline, valleys, lakes, hills and mountains, the plant was the first in the world to mass-produce heavy water, a key element for the production of atomic weapons. Desperate to thwart Nazi Germany’s nuclear ambitions, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the Allies planned a series of sabotage missions to cripple Vemork’s production.

In early 1942, Churchill turned to his new Chief of Combined Operations, Lord Louis Mountbatten, for bold new ways to strike back at Hitler. Among Mountbatten’s eccentric advisors was Geoffrey Pyke, a brilliant but difficult civilian whose out-of-the-box thinking included a secret prewar plan to poll German public opinion by sending disguised golfers into Nazi Germany; a proposal to move supplies and soldiers through pressurized pipelines across battlefields; and the invention of Pykrete, an ice and sawdust composite that he envisioned as the material for massive floating aircraft carriers that could be used to shield Allied convoys in the mid-Atlantic. In a testament to Pyke’s influence, as well as to the impracticality of some of his ideas, the Allies actually built a 60-foot long, 30-foot wide prototype of the vessel on Alberta’s Lake Patricia before discovering it would be cheaper to build a standard aircraft carrier out of steel.

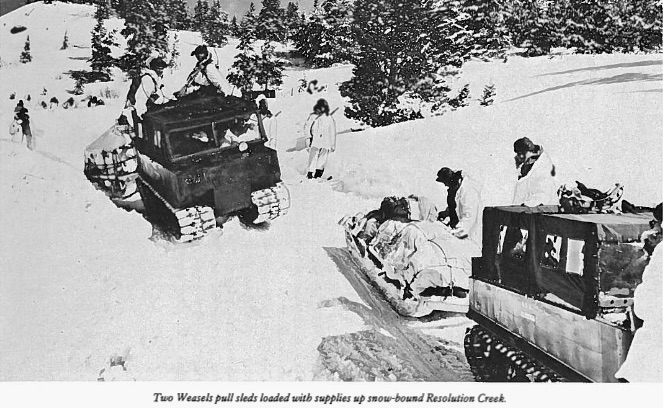

Pyke had also proposed creating a highly mobile winter fighting force that could be inserted deep into Norway’s rugged interior to disrupt German operations. To transport the force, he envisioned snow vehicles that were light enough to traverse deep snow, powerful enough to transport men and draw cargo sleds, small enough to be carried in a transport plane, tough enough to survive an airdrop, and fast enough to evade capture by German ski troops.

Problematically, no such vehicles existed in 1942.

Never one to let an inconvenience get in the way of a good idea, Churchill gave the project his full support. So did President Roosevelt. A date of November was set for the vehicles’ aerial insertion. All that needed to be done was to invent them—and for this, we present the Studebaker Corporation.

Founded in 1852 in South Bend, Indiana, by the brothers Henry and Clement Studebaker, the company had become the world’s largest wagon and carriage manufacturer by the early 1900s, when it began transitioning to the production of electric cars. The same challenges that plague electric cars today—limited range, long charging times—convinced Studebaker to switch its focus to gasoline-powered vehicles, where it eventually made its mark. When World War I broke out, the company pivoted again, to the development of military wagons and trucks. Post war, it continued to grow, diversifying into luxury cars before getting walloped by the Great Depression.

Hardly had the company emerged from receivership than it was forced to retool, once more, for war. By the late 1930s, Studebaker was building military trucks for France and Britain. When the U.S. entered World War II, it again became a key supplier of the country’s military vehicles—and soon found itself working furiously to make Churchill’s mad plan a reality. The project was considered such a priority that it took precedence over the development of the B-17 bomber.

Studebaker began working on the vehicle in April. As the aeriel insertion date approached, its engineers labored overtime until it had a workable prototype: a small, tank-like machine that ran on rubber tracks. The contraption needed to be tested, though, and, with winter’s snows still months away, the search began for a suitable test location.

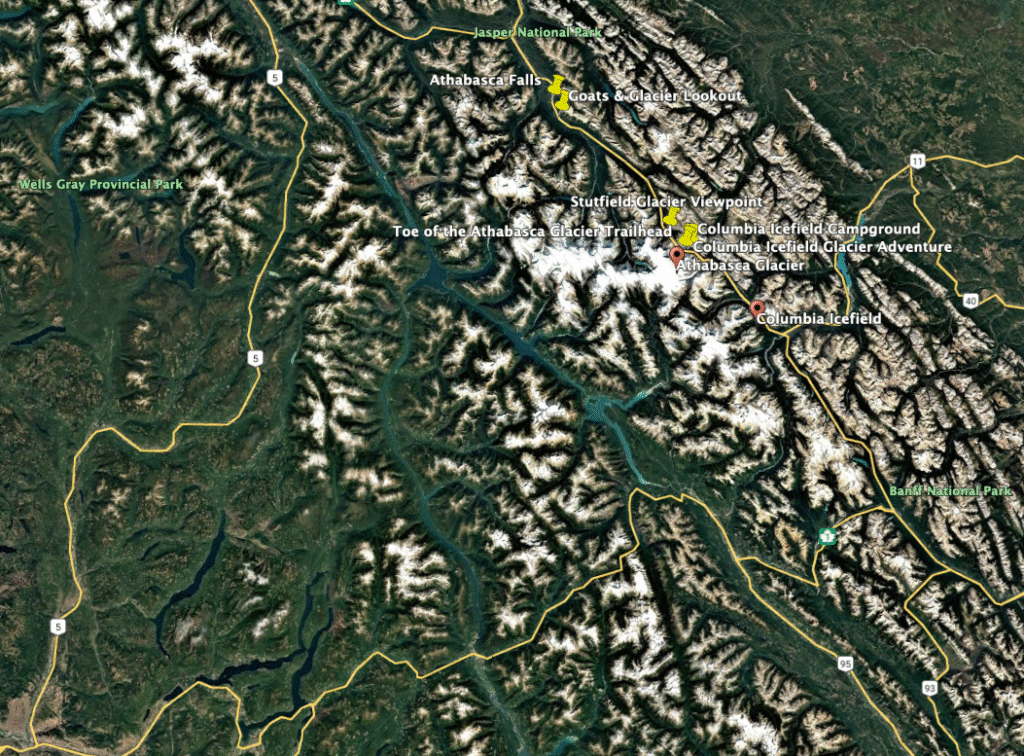

Enter the Columbia Icefield, the largest glaciated terrain in North America’s Rocky Mountains. Located in Banff National Park, some 75 miles northwest of the town of Banff itself, in the shadow of some of the highest mountains in the Canadian Rockies, the icefield straddles the Continental Divide as well as the border of British Columbia and Alberta. With 125 square miles of permanent snowfields and ice depths that range anywhere from 300 to more than 1,000 feet, it was the perfect place to test Studebaker’s new vehicle. There was only one small problem: the nearest road ended eight miles from the icefield itself.

Thus, the 87th’s next special mission.

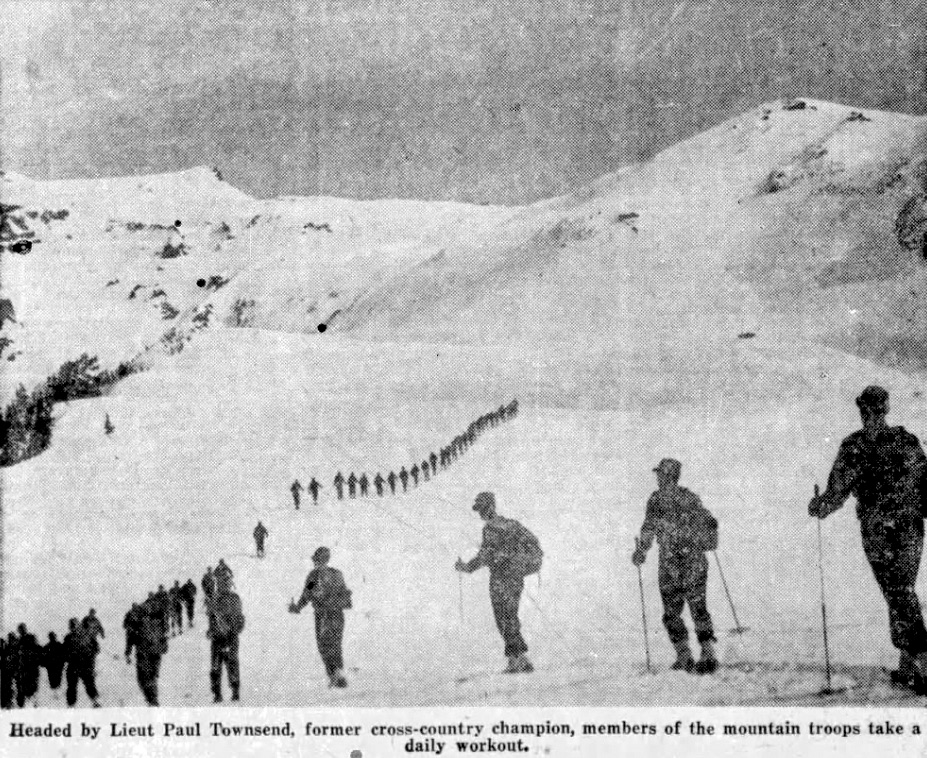

Its commanding officer, Major Robert Tillotson, had served alongside John Jay and Albert Jackman on the Mountain and Winter Warfare Board as the Quartermaster’s representative, procuring everything the 87th had needed to train. For his executive officer, Tillotson chose Lieutenant Paul Townsend, who had barely had time to shower after completing the unit’s test climb of Mt. Rainier before embarking on the assignment. The secret mission also included Hal Burton, who would later document it in his book, The Ski Troops.

With Studebaker covering all the expenses and Army Ground Forces cutting the red tape, Colonel Tillotson, Lieutentant Townsend and the rest of the detachment were soon hard at work in the Canadian Rockies. In twenty six days they’d built a road to the snout of the Saskatchewan Glacier, whereupon they were told their mission: “to build the first roadway in the world,” as Burton put it, “up a glacier to the level floor of the icefields”—and from there, to test Studebaker’s vehicle.